Markovo tajné evangelium - Secret Gospel of Mark

The Markovo tajné evangelium nebo Markovo mystické evangelium[1] (řecký: τοῦ Μάρκου τὸ μυστικὸν εὐαγγέλιον, tou Markou do mystikon euangelion),[A][3] také Delší Markovo evangelium,[4][5] je domnělá delší a tajná nebo mystická verze Markovo evangelium. Evangelium je zmíněno výlučně v Mar Saba dopis, dokument sporné pravosti, o kterém se říká, že jej napsal Klement Alexandrijský (asi 150–215 nl). Tento dopis je zase zachován pouze na fotografiích řecké ručně psané kopie, která se zdánlivě přepisovala v osmnáctém století do předloh tištěného vydání děl ze sedmnáctého století. Ignáce z Antiochie.[b][8][9][10]

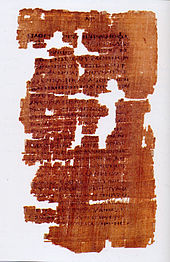

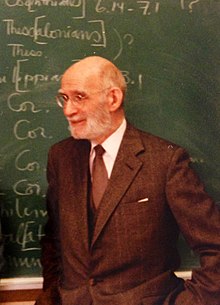

V roce 1958 Morton Smith, profesor starověkých dějin na Columbia University, našel dříve neznámý dopis Klementa Alexandrijského v klášter z Mar Saba leží 20 kilometrů jihovýchodně od Jeruzalém.[11] V roce 1960 formálně oznámil objev[12] a svou studii textu publikoval v roce 1973.[10][13] Originál rukopis byl následně přenesen do knihovny Řecká pravoslavná církev v Jeruzalémě a někdy po roce 1990 byla ztracena.[14][15] Další výzkum se opíral o fotografie a kopie, včetně těch, které vytvořil sám Smith.[16]

V dopise adresovaném jednomu jinak neznámému Theodorovi (Theodoros),[17][18] Clement říká, že „když Peter zemřel jako mučedník, Mark [tj. Označte evangelistu ] přišel do Alexandrie a přinesl jak své vlastní poznámky, tak poznámky Petra, ze kterých přešel do své dřívější knihy [tj. the Markovo evangelium ] věci vhodné pro cokoli, co vede k pokroku směrem k poznání. “[19] Dále říká, že Mark ponechal tuto rozšířenou verzi, dnes známou jako Markovo tajné evangelium, „do kostela v Alexandrii, kde je přesto pečlivě střežen a je čten pouze těm, kteří jsou zasvěceni do velkých tajemství“.[19][20][21] Clement cituje dvě pasáže z tohoto Markova tajného evangelia, kde se říká, že Ježíš v delší pasáži vzkřísil bohatého mladého muže z mrtvých v Bethany.[22] příběh, který sdílí mnoho podobností s příběhem vzkříšení Lazara v Janovo evangelium.[23][24][25]

Odhalení dopisu v té době vyvolalo senzaci, ale brzy se setkalo s obviněním z padělání a zkreslování.[26] Ačkoli většina patristický Clementští učenci přijali dopis jako pravý,[27][28] mezi autenticitou neexistuje shoda bibličtí učenci, a názor je rozdělen.[29][30][31] Protože text je složen ze dvou textů, mohou být oba neautentické nebo oba autentické, nebo jeden je autentický a druhý neautentický.[32] Ti, kdo si myslí, že dopis je padělek, si většinou myslí, že jde o moderní padělek, jehož objevitelem Mortonem Smithem je nejčastěji odsouzeným pachatelem.[32] Pokud je dopis moderním paděláním, byly by výňatky z Markova tajného evangelia také padělky.[32] Někteří přijímají dopis jako pravý, ale nevěří v Clementovu zprávu, místo toho tvrdí, že evangelium je druhé století (gnostický ) pastiche.[33][34] Jiní si myslí, že Clementovy informace jsou přesné a že tajné evangelium je druhým vydáním Markovo evangelium rozšířeno o Označit sám.[35] Ještě jiní vidí Marekovo tajné evangelium jako původní evangelium, které předcházelo kanonickému Markovo evangelium,[36][37] a kde kanonická značka je výsledkem pasáží tajné značky citovaných Clementem a dalších pasáží, které byly odstraněny, buď samotným Markem, nebo někým jiným v pozdější fázi.[38][39]

O autentičnosti dopisu Mar Saba se stále vede polemika.[40] Vědecká komunita je rozdělena, pokud jde o autenticitu, a debata o Secret Mark tedy ve stavu patové situace,[41][32][26] ačkoli debata pokračuje.[42]

Objev

Morton Smith a objev dopisu Mar Saba

Během cesty do Jordán, Izrael, krocan, a Řecko v létě 1958 „lov sbírek rukopisů“,[44] Morton Smith také navštívil Řecký ortodoxní klášter Mar Saba[45] umístěný mezi Jeruzalém a Mrtvé moře.[46] Povolení mu bylo uděleno Jeruzalémský patriarcha Benedikt I. zůstat tam tři týdny a studovat jeho rukopisy.[47][43] Později uvedl, že při katalogizaci dokumentů ve věžové knihovně Mar Saba objevil dříve neznámý dopis, který napsal Klement Alexandrijský ve kterém Clement citoval dvě pasáže z obdobně dříve neznámé delší verze Markovo evangelium, kterou Smith později nazval „Markovým tajným evangeliem“.[7] Text dopisu byl ručně psán do předních tapet Isaac Vossius "1646 tištěných vydání děl Ignáce z Antiochie.[b][7][6][8][9] Tento dopis je označován mnoha jmény, včetně Mar Saba dopis, Klementův dopis, Dopis Theodorovi a Clementův dopis Theodorovi.[48][49][50][51][52][53]

Protože kniha byla "majetkem Řecký patriarchát “, Smith právě pořídil několik černobílých fotografií dopisu a nechal knihu, kde ji našel, ve věže knihovny.[10] Smith si uvědomil, že pokud má list ověřit, musí se o jeho obsah podělit s dalšími učenci. V prosinci 1958 předložil a., Aby zajistil, že nikdo nezveřejní její obsah předčasně transkripce dopisu s předběžným překladem do Knihovna Kongresu.[C][55]

Poté, co jsem strávil dva roky srovnáváním stylu, slovní zásoby a myšlenek Klementova dopisu Theodorovi s nespornými spisy Klementa Alexandrijského[56][57][10][58] a po konzultaci s několika paleografický odborníci, kteří datovali rukopis do osmnáctého století,[59][60] Smith si byl dostatečně jistý svou autenticitou, a tak oznámil svůj objev na výročním zasedání Společnost biblické literatury v prosinci 1960.[10][61][d] V následujících letech důkladně studoval Označit, Clement a pozadí a vztah dopisu k rané křesťanství,[56] během této doby konzultoval mnoho odborníků z příslušných oborů. V roce 1966 v podstatě dokončil studium, ale výsledek byl ve formě vědecké knihy Klement Alexandrijský a Markovo tajné evangelium[63] byla zveřejněna až v roce 1973 kvůli sedmiletému zpoždění „ve fázi výroby“.[10][64] V knize Smith publikoval soubor černobílých fotografií textu.[65] Dříve téhož roku vydal také druhou knihu pro populární publikum.[66][67][68]

Následná historie rukopisu

Po mnoho let se předpokládalo, že rukopis viděl pouze Smith.[69] Nicméně v roce 2003 Guy Stroumsa uvedl, že on a skupina dalších vědců to viděli v roce 1976. Stroumsa, spolu s pozdě Hebrejská univerzita profesoři David Flusser a Shlomo Pines a řecký ortodoxní Archimandrit Meliton šel do Mar Saba knihu hledat. S pomocí mnicha Mar Saba jej přemístili tam, kde jej Smith pravděpodobně nechal před 18 lety, a „Clementovým dopisem napsaným na prázdné stránky na konci knihy“.[70] Stroumsa, Meliton a společnost zjistili, že rukopis může být v Jeruzalémě bezpečnější než v Mar Saba. Vzali knihu zpět s sebou a Meliton ji následně přinesl do knihovny patriarchátu. Skupina zkoumala inkoust otestovaný, ale jedinou entitou v oblasti s takovou technologií byla Jeruzalémská policie. Meliton nechtěl zanechat rukopis policii, takže nebyl proveden žádný test.[71][72] Stroumsa zveřejnil svůj účet poté, co se dozvěděl, že byl „posledním [známým] žijícím západním učencem“, který dopis viděl.[71][14][73]

Následný výzkum odhalil více o rukopisu. Kolem roku 1977,[74] knihovník otec Kallistos Dourvas odstranil dvě stránky obsahující text z knihy za účelem jejich fotografování a opětovné katalogizace.[75] K opětovné katalogizaci však očividně nikdy nedošlo.[15] Dourvas později řekl Charlesi W. Hedrickovi a Nikolaosovi Olympiouovi, že stránky byly poté vedeny odděleně vedle knihy alespoň do svého odchodu do důchodu v roce 1990.[76] Někdy poté však stránky zmizely a různé pokusy o jejich nalezení od té doby byly neúspěšné.[72] Olympiou navrhuje, aby jednotlivci v knihovně patriarchátu mohli zadržovat stránky kvůli homoerotické interpretaci textu Mortona Smitha,[77][78][79] nebo by stránky mohly být zničeny nebo nesprávně umístěny.[75] Kallistos Dourvas dal barevné fotografie rukopisu Olympiou a Hedrick a Olympiou je publikovali v Čtvrtý R. v roce 2000.[14][15]

Tyto barevné fotografie vytvořil v roce 1983 Dourvas at a fotografické studio. Ale toto zařídil a zaplatil Quentin Quesnell. V červnu 1983[80] Quesnell dostal povolení studovat rukopis v knihovně několik dní během třítýdenního období[81] pod dohledem Dourvase.[82] Quesnell byl „prvním učencem, který formálně uvedl, že by dokument Mar Saba mohl být padělek“, a byl „nesmírně kritický“ vůči Smithovi, zejména kvůli tomu, že dokument nedal k dispozici svým vrstevníkům a poskytl takové nekvalitní fotografie.[83][84] Quesnell přesto svým kolegům neřekl, že rukopis také prozkoumal, a neodhalil, že by tyto vysoce kvalitní barevné fotografie dopisu měl doma již v roce 1983.[85] Když Hedrick a Olympiou publikovali stejné fotografie v roce 2000[86] protože si Dourvas nechal kopie pro sebe, nebyli si toho vědomi.[87] Vědecká komunita nevěděla o Quesnellově návštěvě až do roku 2007 Adela Yarbro Collins stručně zmínil, že mu bylo umožněno nahlédnout do rukopisu na začátku 80. let.[88][85] Několik let po Quesnellově smrti v roce 2012 dostali vědci přístup k poznámkám z jeho cesty do Jeruzaléma.[89] Ukazují, že Quesnell si zpočátku věřil, že dokáže prokázat, že dokument byl padělek.[90] Ale když našel něco, co považoval za podezřelé, Dourvas (který si byl jist, že jde o autentický rukopis z osmnáctého století)[91] by představoval další rukopis z osmnáctého století s podobnými vlastnostmi.[90] Quesnell připustil, že jelikož „nejsou všichni padělky“, nebylo by tak snadné dokázat, že text je padělek, jak čekal. Nakonec se pokusů vzdal a napsal, že je třeba konzultovat odborníky.[92]

Od roku 2019 není místo rukopisu známo,[93] a je to dokumentováno pouze ve dvou sadách fotografií: Smithově černobílé sadě z roku 1958 a barevné sadě z roku 1983.[82] Inkoust a vlákno nebyly nikdy podrobeny zkoumání.[94]

Obsah podle Clementova dopisu

Dopis Mar Saba je adresován jednomu Theodoreovi (řecký: Θεόδωρος, Theodoros),[18] který se, zdá se, zeptal, zda existuje Markovo evangelium, ve kterém slova „nahý muž s nahým mužem“ (řecký: γυμνὸς γυμνῷ, gymnos gymnō) a „další věci“ jsou přítomny.[96] Clement potvrzuje, že Mark napsal druhou, delší, mystickou a duchovnější verzi svého evangelia a že toto evangelium bylo „velmi bezpečně uchováváno“ v Alexandrijský kostel, ale že neobsahovala žádná taková slova.[96] Clement obviňuje heterodoxní učitel Carpocrates za to, že kopii získal podvodem, a poté ji znečistil „naprosto nestydatými lžemi“. Vyvrátit učení gnostický sekta Carpocratians, známý pro jejich sexuální libertarianismus,[97][98] a aby ukázal, že tato slova ve skutečném Markově tajném evangeliu chyběla, citoval z něj Clement dvě pasáže.[99][38]

Podle toho byly Clementovi známy tři verze Marka, Původní značka, Tajná značka, a Carpocratian Mark.[21] Markovo tajné evangelium je popisováno jako druhá „duchovnější“ verze Markovo evangelium složil sám evangelista.[25] Název je odvozen od Smithova překladu výrazu „mystikon euangelion“. Klement však jednoduše odkazuje na evangelium, které napsal Marek. Aby rozlišil mezi delší a kratší verzí Markova evangelia, dvakrát odkazuje na nekanonické evangelium jako na „mystikon euangelion“[100] (buď tajné evangelium, jehož existence byla skryta, nebo mystické evangelium „týkající se tajemství“[101] se skrytými významy),[E] stejným způsobem, jako o něm mluví jako o „duchovnějším evangeliu“.[4] „Klementovi, oba verze byly Markovým evangeliem ".[102] Účelem evangelia bylo údajně povzbudit poznání (gnóza ) mezi pokročilejšími křesťany a údajně se používá v liturgie v Alexandrie.[25]

Citáty od Secret Mark

Dopis obsahuje dva výňatky z Tajného evangelia. Clement říká, že první pasáž byla vložena mezi Marka 10:34 a 35; po odstavci, kde Ježíš na své cestě do Jeruzaléma s učedníky učinil třetí předpověď své smrti, a před Marekem 10:35 a dále, kde učedníci James a John požádejte Ježíše, aby jim udělil čest a slávu.[103] Ukazuje mnoho podobností s příběhem v Janovo evangelium 11: 1–44, kde Ježíš vzkřísil Lazara z mrtvých.[23][24] Podle Clementa pasáž čte slovo od slova (řecký: κατὰ λέξιν, kata lexin):[104]

A přišli do Betánie. A byla tam jistá žena, jejíž bratr zemřel. A když přišla, poklonila se před Ježíšem a řekla mu: „Synu Davidův, smiluj se nade mnou.“ Učedníci jí však vytkli. A rozhněvaný Ježíš odešel s ní do zahrady, kde byl hrob, a hned bylo z hrobky slyšet velký výkřik. A když se Ježíš přiblížil, odvalil kámen ze dveří hrobky. A hned, když vešel tam, kde byl mladík, natáhl ruku, zvedl ho a chytil ho za ruku. Ale mladík, který se na něj díval, ho miloval a začal ho prosit, aby mohl být s ním. A když vyšli z hrobky, přišli do domu mládence, protože byl bohatý. A po šesti dnech mu Ježíš řekl, co má dělat, a večer k němu přišel mladík, který měl na svém nahém těle plátěnou látku. A zůstal s ním té noci, protože Ježíš ho naučil tajemství Božího království. Odtamtud se vrátil a vrátil se na druhou stranu Jordánu.[19]

Druhý výňatek je velmi stručný a byl vložen do Marka 10:46. Clement říká, že „po slovech:„ A on přichází do Jericha “[a před ním“ a když vyšel z Jericha „] tajné evangelium dodává pouze“:[19]

A sestra mladého, kterého Ježíš miloval, a jeho matka a Salome tam byli, a Ježíš je nepřijal.[19]

Clement pokračuje: „Ale mnoho dalších věcí, o kterých jsi napsal, se zdá být a jsou padělání.“[19] Právě když se Clement chystá pravdivě vysvětlit jednotlivé pasáže, dopis se odlomí.

Tyto dva výňatky obsahují celý materiál Secret Evangelium. Není známo, že by přežil žádný samostatný text tajného evangelia, a není na něj odkazováno v žádném jiném starověkém zdroji.[105][106][107] Někteří vědci považují za podezřelé, že autentický starověký křesťanský text bude zachován pouze v jediném pozdním rukopisu.[31][108] To však není bezprecedentní.[109][F]

Debata o autentičnosti a autorství

70. a 80. léta

Recepce a analýza Mortona Smitha

Mezi vědci neexistuje jednotný názor na pravost dopisu,[110][30][31] v neposlední řadě proto, že inkoust rukopisu nebyl nikdy testován.[30][111] Na začátku nebylo pochyb o pravosti dopisu,[34] a první recenzenti Smithových knih se obecně shodli na tom, že dopis byl pravý.[112] Brzy však došlo k podezření a dopis dosáhl proslulosti, hlavně „protože byl propojen“ s vlastními interpretacemi Smitha.[12] Prostřednictvím podrobných lingvistických výzkumů Smith tvrdil, že by to mohl být pravděpodobně pravý Clementův dopis. Naznačil, že tyto dvě citace se vracejí k originálu Aramejština verze Mark, která sloužila jako zdroj pro kanonická značka a Janovo evangelium.[113][12][114][115] Smith tvrdil, že křesťanské hnutí začalo jako tajemné náboženství[116] s obřady zasvěcení křtu,[G][96] a že historický Ježíš byl mág posedlý Duchem,[117] Smithovým recenzentům nejvíce znepříjemňoval jeho návrh, že křestní iniciační obřad, který Ježíš svým učedníkům poskytl, mohl jít až k fyzickému spojení.[116][h][i]

Autentičnost a autorství

V první fázi byl dopis považován za pravý, zatímco Secret Mark byl často považován za typické neautentické evangelium druhého století vycházející z kanonických tradic.[34] Tuto teorii pastiche prosazoval F. F. Bruce (1974), kteří viděli příběh mladého muže z Bethany neobratně na základě vzkříšení Lazara v Janově evangeliu. Viděl tedy příběh Secret Mark jako derivát a popřel, že by mohl být zdrojem Lazarova příběhu nebo nezávislou paralelou.[118] Raymond E. Brown (1974) dospěli k závěru, že autor Tajného Marka „mohl dobře vycházet z„ Janova evangelia “,„ alespoň z paměti “.[119] Patrick W. Skehan (1974) tento názor podpořili a spoléhání na Johna označili za „nezaměnitelnou“.[120] Robert M. Grant (1974) si myslel, že Smith rozhodně dokázal, že dopis napsal Clement,[121] ale nalezené v prvcích Secret Mark z každého ze čtyř kanonických evangelií,[j][122] a dospěl k závěru, že byl napsán po prvním století.[123] Helmut Merkelová (1974) také dospěla k závěru, že Secret Mark je po analýze klíčových řeckých frází závislý na čtyřech kanonických evangeliích,[124] a že i když je dopis pravý, neříká nám nic víc, než že v něm existovala rozšířená verze Marka Alexandrie v inzerátu 170.[117] Frans Neirynck (1979) tvrdil, že Secret Mark byl prakticky „složen za pomoci shody“ kanonických evangelií[125] a zcela na nich závislý.[126][127] N. T. Wright napsal v roce 1996, že většina vědců, kteří přijímají text jako pravý, vidí v Markově tajném evangeliu „podstatně pozdější adaptaci Marka v rozhodně gnostický směr."[128]

Přibližně stejný počet vědců (nejméně 25) však nepovažoval Secret Mark za „bezcennou výmysl patchworků“, ale místo toho viděl uzdravující příběh podobně jako jiné zázračné příběhy v Synoptická evangelia; příběh, který postupoval hladce bez zjevných hrubých souvislostí a nekonzistencí, jak se nachází v odpovídajícím příběhu vzkříšení Lazara v Janovo evangelium. Stejně jako Smith si většinou mysleli, že příběh je založen na ústní tradice, i když obecně odmítali jeho představu aramejského proto-evangelia.[129]

Quentin Quesnell a Charles Murgia

Prvním učencem, který veřejně zpochybnil pravost dopisu, byl Quentin Quesnell (1927–2012) v roce 1975.[130] Quesnellovým hlavním argumentem bylo, že skutečný rukopis musel být prozkoumán, než mohl být považován za autentický,[131] a navrhl, že by to mohl být moderní podvod.[132][34] Řekl, že publikace Otta Stählina shoda Klementa v roce 1936,[133] umožnilo by napodobit Clementův styl,[134][34] což znamená, že pokud se jedná o padělek, bylo by to nutně paděláno po roce 1936.[135][136] Na svůj poslední den pobytu v klášteře našel Smith katalog z roku 1910, ve kterém bylo uvedeno 191 knih,[137][138][139] ale ne kniha Vossius. Quesnell a další tvrdili, že tato skutečnost podporuje domněnku, že kniha nikdy nebyla součástí knihovny Mar Saba,[140] ale byl tam přiveden zvenčí, například Smith, s již napsaným textem.[141][142] To však bylo zpochybněno. Smith během svého pobytu našel téměř 500 knih,[k][144] takže seznam nebyl zdaleka úplný[145] a mlčení z neúplných katalogů nelze použít jako argumenty proti existenci knihy v době, kdy byl katalog vytvořen, argumentoval Smith.[137]

Ačkoli Quesnell neobviňoval Morton Smith zfalšování dopisu jeho „hypotetický padělatel odpovídal Smithově zjevné schopnosti, příležitosti a motivaci“ a čtenáři článku, stejně jako Smith sám, to považovali za obvinění, že viníkem byl Smith.[82][34] Vzhledem k tomu, že v té době nikdo kromě Smitha rukopis neviděl, někteří učenci navrhli, že by ani nemusel existovat rukopis.[34][l]

Charles E. Murgia následoval Quesnellova tvrzení o padělání dalšími argumenty,[146] například upozornit na skutečnost, že rukopis nemá žádné vážné písařské chyby, jak by se dalo očekávat od mnohokrát kopírovaného starodávného textu,[147][117][148] a tím, že naznačuje, že text Klementa byl navržen jako a sphragis „pečeť autenticity“, aby odpověděla na otázky čtenářů, proč o Secret Mark nikdy předtím neslyšel.[149] Murgia zjistil, že Klementovo nabádání k Theodorovi, že by neměl připustit, aby Carpocratians „že tajné evangelium je podle Marka, ale měl by to dokonce popřísahat“,[19] být směšný, protože nemá smysl „naléhat na někoho, aby spáchal křivou přísahu, aby uchoval tajemství něčeho, co právě zveřejňujete“.[150] Později Jonathan Klawans, který si myslí, že dopis je podezřelý, ale možná autentický, podpořil argument Murgie tím, že kdyby Clement vyzval Theodora, aby lhal Karokratům, bylo by pro něj snazší dodržovat „jeho vlastní radu a“ lhát Theodorovi namísto.[151] Scott Brown však považuje tento argument za chybný, protože nemá smysl popírat existenci evangelia, které mají Karokratové ve svém držení. Brown se zasazuje o to, aby Theodore místo toho ujistil, že falšované nebo padělané karokratovské evangelium nenapsal Mark, což by podle Browna bylo přinejmenším polopravdou a také něčím, co by Clement mohl říci ve prospěch církve.[152]

Smith přemýšlel o Murgia argumentech, ale později je odmítl jako založené na nesprávném čtení,[34] a myslel si, že Murgia „upadla do několika faktických chyb“.[153][154] Ačkoli padělatel používá techniku „vysvětlování vzhledu a ručení za autenticitu“, stejná forma se také často používá k prezentaci dosud neslýchaného materiálu.[153] A přestože žádný z Clementových dalších dopisů nepřežil,[108][155] zdá se, že tam byla sbírka nejméně dvaceti jedna z jeho dopisů Mar Saba v osmém století, kdy Jan Damašek, který tam pracoval více než 30 let (asi 716–749), citoval z této sbírky.[156][m] A na počátku osmnáctého století velký požár u Mar Saba vypálil jeskyni, ve které bylo uloženo mnoho nejstarších rukopisů. Smith spekuloval, že Clementův dopis mohl požár částečně přežít a mnich ho mohl zkopírovat do předních listů klášterního vydání Ignácových dopisů[b] aby byla zachována.[159][160] Smith tvrdil, že nejjednodušším vysvětlením by bylo, že text byl „zkopírován z rukopisu, který ležel po tisíciletí nebo více v Mar Saba a nikdy o něm nebylo slyšet, protože nikdy nebyl mimo klášter.“[153][161]

Murgia každopádně vyloučil možnost, že Smith mohl padělat dopis, protože podle něj byla Smithova znalost řečtiny nedostatečná a nic v jeho knize nenaznačovalo podvod.[162] Murgia si zdánlivě myslela, že dopis byl vytvořen v osmnáctém století.[163]

Morton Smith namítal proti narážkám, že by tento dopis zfalšoval, například voláním článku Quesnella z roku 1975[164] útok.[165][166] A když švédský historik Per Beskow v Zvláštní příběhy o Ježíši od roku 1983,[167] první anglické vydání jeho 1979 švédský rezervovat,[n] napsal, že existují důvody být skeptičtí ohledně pravosti dopisu, Smith se rozčilil a reagoval vyhrožováním žalováním vydavatele v anglickém jazyce, Fortress Press of Philadelphia za milion dolarů.[168][169] To způsobilo, že pevnost stáhla knihu z oběhu a v roce 1985 vyšlo nové vydání, ve kterém byly odstraněny pasáže, proti nimž měl Smith námitky,[170] a Beskow zdůraznil, že neobvinil Smitha, že to padělal.[169] Ačkoli měl Beskow pochybnosti o pravosti dopisu, upřednostňoval „to považovat za otevřenou otázku“.[169]

Priorita tajného Markana

Morton Smith shrnul situaci v článku z roku 1982. Myslel tím, že „většina učenců by dopis připisovala Clementovi“ a že nebyl předložen žádný pádný argument.[171][33] Připisování evangelia Označit byl „všeobecně odmítnut“, přičemž nejběžnějším názorem bylo, že evangelium je „pastiška složená z kanonických evangelií“ ve druhém století.[33][Ó]

Po Smithově shrnutí situace další učenci podpořili prioritu Secret Markan. Ron Cameron (1982) a Helmut Koester (1990) tvrdili, že Secret Mark předcházel kanonickému Marku, což by ve skutečnosti byla zkratka pro Secret Mark.[p] Hans-Martin Schenke s několika úpravami podpořil Koesterovu teorii,[176][36] a také John Dominic Crossan představil do určité míry podobnou „pracovní hypotézu“ jako Koester: „Domnívám se, že kanonický Marek je velmi záměrnou revizí Tajná značka."[177][178] Marvin Meyer zahrnoval Secret Mark do své rekonstrukce původu Markova evangelia.[179][180]

1991 (po Smithově smrti) do roku 2005

Zintenzivnění obvinění proti Smithovi

Obvinění proti Smithovi za padělání rukopisu Mar Saba se stala ještě výraznější po jeho smrti v roce 1991.[181][182][94] Jacob Neusner, specialista na starověké judaismus, byl studentem a obdivovatelem Mortona Smitha, ale později, v roce 1984, mezi nimi došlo k pádu veřejnosti poté, co Smith veřejně odsoudil akademické schopnosti svého bývalého studenta.[183] Neusner následně popsal Secret Mark jako „padělání století“.[184][185] Neusner přesto nikdy nenapsal žádnou podrobnou analýzu Tajného Marka ani vysvětlení, proč si myslel, že jde o padělek.[q]

Jazyk a styl Clementova dopisu

Většina vědců, kteří mají „prostudoval dopis a napsal na toto téma„předpokládejme, že dopis napsal Clement.[187][188] Většina patristických učenců si myslí, že jazyk je pro Clementa typický, a že se zdá, že dopis byl napsán způsobem a hmotou.[27] V „první epištolské analýze Clementova dopisu Theodorovi“ Jeff Jay prokazuje, že dopis „se shoduje formou, obsahem a funkcí s jinými starodávnými dopisy, které se zabývaly podobnými okolnostmi“,[189] a „je věrohodné ve světle psaní dopisů na konci druhého nebo počátku třetího století“.[190] Tvrdí, že k zfalšování tohoto dopisu by bylo zapotřebí padělatel s tak rozsáhlou znalostí, která je „nadlidská“.[r] Clementinští učenci v zásadě přijali autentičnost dopisu a v roce 1980 byl také zahrnut do shoda uznaných skutečných spisů Klementa,[133][28] ačkoli toto zařazení říká redaktorka Ursula Treu jako provizorní.[192][193]

V roce 1995 Andrew H. Criddle provedl statistickou studii Clementova dopisu Theodorovi pomocí shody Otta Stählina s Clementovými spisy.[133][48] Podle Criddla měl dopis příliš mnoho hapax legomena, slova použitá Clementem pouze jednou, ve srovnání se slovy, která Clement nikdy předtím nepoužíval, a Criddle tvrdil, že to naznačuje, že padělatel „spojil více vzácných slov a frází“ nalezených v autentických Clementových spisech, než by použil Clement .[194] Studie byla kritizována mimo jiné se zaměřením na „nejméně oblíbená Clementova slova“ a za samotnou metodiku, která se ukazuje jako „nespolehlivá při určování autorství“.[195] Při testování na Shakespeare spisy byly správně identifikovány pouze tři ze sedmi básní.[196][197][s]

Tajemství Mar Saba

V roce 2001 Philip Jenkins upozornil na román od James H. Hunter oprávněný Tajemství Mar Saba, který se poprvé objevil v roce 1940 a byl v té době populární.[199][200] Jenkins viděl neobvyklé paralely s Clementovým dopisem Theodorovi a Smithově popisu jeho objevu v roce 1958,[201] ale výslovně neuváděl, že román inspiroval Smitha k padělání textu.[202] Později Robert M. Price,[203] Francis Watson[204] a Craig A. Evans[205] vyvinul teorii, že Morton Smith by byl inspirován tímto románem, aby vytvořil dopis. Tento předpoklad zpochybnil mimo jiné Scott G. Brown, který píše, že kromě „učence objevujícího dříve neznámý starověký křesťanský rukopis u Mar Saba existuje jen málo paralel“[206][t] - a při vyvrácení Evanse spolu s Allanem J. Pantuckem najdou údajnou paralelu mezi Scotland Yard Příjmení detektiva lorda Moretona a křestní jméno Mortona Smitha jsou matoucí, protože Morton Smith dostal své jméno dlouho předtím, než byl román napsán.[208] Francis Watson považuje paralely za tak přesvědčivé, že „otázce závislosti se nelze vyhnout“,[209] zatímco Allan J. Pantuck si myslí, že jsou příliš obecní nebo příliš chytří na to, aby přesvědčovali.[210] Javier Martínez, který si myslí, že otázka padělání je otevřená debatě, se domnívá, že Hunterův román by inspiroval Smitha, aby text zfalšoval.[211] Zajímalo by ho, proč to trvalo více než čtyři desetiletí poté, co se příběh Smithova objevu dostal na přední stranu časopisu New York Times[u] než si někdo uvědomil, že tento tak populární román byl Smithovým zdrojem.[212] Martínez najde Watsonovy metody, kterými došel k závěru, že „[zde] není jiná alternativa, než dojít k závěru, že Smith je závislý na“ Tajemství Mar Saba,[213] být „neskutečný jako vědecké dílo“.[214] Timo Paananen tvrdí, že ani Evans, ani Watson nevyjasňují, jaká kritéria používají k prokázání toho, že tyto konkrétní paralely jsou tak „úžasné jak v podstatě, tak v jazyce“,[215][216] a že snižují přísnost svých kritérií ve srovnání s tím, jak odmítají „literární závislosti v jiném kontextu“.[217]

Chiasms in Mark

V roce 2003 navrhl John Dart komplexní teorii „chiasmat“ (nebo „optická vada ') běžící přes Markovo evangelium - druh literárního zařízení, které v textu najde.[218] „Obnovuje formální strukturu původního Marka obsahujícího pět hlavních chiastických rozpětí zarámovaných prologem a závěrem.“[219] Podle Darta jeho analýza podporuje autentičnost Secret Mark.[219] Jeho teorie byla kritizována, protože předpokládá hypotetické změny v textu Marka, aby mohl fungovat.[220]

Pat v akademii

Skutečnost, že po mnoho let nebylo známo, že by rukopis viděli kromě Smitha i jiní učenci, přispěla k podezření z padělání.[224] To se rozptýlilo vydáním barevných fotografií v roce 2000,[86] a odhalení v roce 2003, že Guy Stroumsa a několik dalších si prohlédli rukopis v roce 1976.[71][14] V reakci na myšlenku, že Smith zabránil jiným vědcům v inspekci rukopisu, Scott G. Brown poznamenal, že k tomu není v pozici.[14] The manuscript was still where Smith had left it when Stroumsa and company found it eighteen years later,[71] and it did not disappear until many years after its relocation to Jerusalem and its separation from the book.[14] Charles Hedrick says that if anyone is to be blamed for the loss of the manuscript, it is the "[o]fficials of the Greek Orthodox Patriarchate in Jerusalem ", as it was lost while it was in their custody.[16]

In 2003 Charles Hedrick expressed frustration over the stalemate in the academy over the text's authenticity,[36] even though the Clementine scholars in the main had accepted the authenticity of the letter.[28] And the same year Bart Ehrman stated that the situation still was the same as it was when Smith summarized it in 1982, namely that a majority of scholars considered the letter to be authentic, "and probably a somewhat smaller majority agreed that the quotations of Secret Mark actually derived from a version of Mark."[30][221]

The two camps could be illustrated, on the one hand by Larry Hurtado, who thinks it is "inadvisable to rest too much on Secret Mark" as the letter "that quotes it might be a forgery" and even if it is genuine, Secret Mark "may be at most an ancient but secondary edition of Mark produced in the second century by some group seeking to promote its own esoteric interests",[225] a tím Francis Watson, who hopes and expects that Secret Mark will be increasingly ignored by scholars to avoid "that their work will be corrupted by association with it".[226] On the other hand by Marvin Meyer, who assumes the letter to be authentic and in several articles, beginning in 1983,[227] used Secret Mark in his reconstructions, especially regarding the young man (neaniskos) "as a model of discipleship",[36][179] and by Eckhard Rau, who argues that as long as a physical examination of the manuscript is not possible and no new arguments against authenticity can be put forward, it is, although not without risk, judicious to interpret the text as originating from the circle of Clement of Alexandria.[228]

Other authors, like an Origenist monk in the early fifth century, have also been proposed for the letter.[229] Michael Zeddies has recently suggested that the letter was actually written by Origenes z Alexandrie (c. 184–c. 254).[230] The author of the letter is identified only in the title[231] and many ancient writings were misattributed.[232][233] According to Zeddies, the language of the letter, its concept and style, as well as its setting, "are at least as Origenian as they are Clementine".[234] Origen was also influenced by Clement and "shared his background in the Alexandrian church".[235] Furthermore, Origen actually had a pupil named Theodore.[236]

2005 to the present

The debate intensified with the publication of three new books.[237] Scott G. Brown's revised doctoral dissertation Mark's Other Gospel od roku 2005,[238][72] byl první monografie that dealt only with Secret Mark since Smith's books in 1973.[63][66][77] Brown argued that both the letter and Secret Mark were authentic.[239] The same year Stephen C. Carlson published The Gospel Hoax[240] in which he spells out his case that Morton Smith, himself, was both the author and the scribe of the Mar Saba manuscript.[239] And in 2007, muzikolog Peter Jeffery zveřejněno The Secret Gospel of Mark Unveiled, in which he accuses Morton Smith of having forged the letter.[241]

Mark's Other Gospel

v Mark's Other Gospel (2005),[238] Scott G. Brown challenged "all previous statements and arguments made against the letter's authenticity"[239] and he criticized those scholars saying that the letter was forged for not offering proof for their claims,[242] and for not making a distinction between the letter and Smith's own interpretation of it.[77] Brown claimed that Smith could not have forged the letter since he did not comprehend it "well enough to have composed it."[243] Brown also criticized the pastiche theory, according to which Secret Mark would be created from a patchwork of phrases from especially the Synoptická evangelia, for being speculative, uncontrollable and "unrealistically complicated".[244] Most parallels between Secret Mark and Matouši a Luke are, according to Brown, "vague, trivial, or formulaic".[245] The only close parallels are to canonical Mark, but a characteristic of Mark is "repetition of exact phrases",[246] and Brown finds nothing suspicious in the fact that a longer version of the Gospel of Mark contains "Markan phrases and story elements".[247] He also explored several Markan literary characteristics in Secret Mark, such as verbal echoes, intercalations and framing stories, and came to the conclusion that the author of the Secret Gospel of Mark "wrote so much like Mark that he could very well be Mark himself",[239] that is, whoever "wrote the canonical gospel."[248]

The Gospel Hoax

v The Gospel Hoax (2005)[240] Stephen C. Carlson argued that Clement's letter to Theodore is a forgery and only Morton Smith could have forged it, as he had the "means, motive, and opportunity" to do so.[249] Carlson claimed to have identified concealed jokes left by Smith in the letter which according to him showed that Smith created the letter as a hoax.[249] He especially identified two: 1) a reference to salt that "loses its savor", according to Carlson by being mixed with an adulterant, and that presupposes free-flowing salt which in turn is produced with the help of an anti-caking agent, "a modern invention" by an employee of the Mortone Salt Company – a clue left by Mortone Smith pointing to himself;[250][77] and 2) that Smith would have identified the handwriting of the Clement letter as done by himself in the twentieth century "by forging the same eighteenth-century handwriting in another book and falsely attributing that writing to a pseudonymous twentieth-century individual named M. Madiotes [Μ. Μαδιότης], whose name is a cipher pointing to Smith himself."[251] The M would stand for Morton, and Madiotes would be derived from the Greek verb μαδώ (madō) meaning both "to lose hair" and figuratively "to swindle" – and the bald swindler would be the balding Morton Smith.[252][253] When Carlson examined the printed reproductions of the letter found in Smith's scholarly book,[63] he said he noted a "forger's tremor."[254] Thus, according to Carlson the letters had not actually been written at all, but drawn with shaky pen lines and with lifts of the pen in the middle of strokes.[255] Many scholars became convinced by Carlson's book that the letter was a modern forgery and some who previously defended Smith changed their position.[proti] Craig A. Evans, for instance, came to think that "the Clementine letter and the quotations of Secret Mark embedded within it constitute a modern hoax, and Morton Smith almost certainly is the hoaxer."[257][258][77]

Yet these theories by Carlson have, in their own turn, been challenged by subsequent scholarly research, especially by Scott G. Brown in numerous articles.[259][260][261][262][263] Brown writes that Carlson's Morton Salt Company clue "is one long sequence of mistakes" and that "the letter nowhere refers to salt being mixed with anything" – only "the true things" are mixed.[264] He also says that salt can be mixed without being free-flowing with the help of mortar and pestle,[265] an objection that gets support from Kyle Smith, who shows that according to ancient sources salt both could be and was "mixed and adulterated".[266][267] Having got access to the uncropped original photograph, Allan Pantuck and Scott Brown also demonstrated that the script Carlson thought was written by M. Madiotes actually was written by someone else and was an eighteenth-century hand unrelated to Clement's letter to Theodore; that Smith did not attribute that handwriting to a contemporary named M. Madiotes (M. Μαδιότης), and that he afterwards corrected the name Madiotes na Madeotas (Μαδεότας) which may, in fact, be Modestos (Μοδέστος), a common name at Mar Saba.[268][269]

In particular, on the subject of the handwriting, Roger Viklund in collaboration with Timo S. Paananen has demonstrated that "all the signs of forgery Carlson unearthed in his analysis of the handwriting", such as a "forger's tremor",[270] are only visible in the images Carlson used for his handwriting analysis. Carlson chose "to use the halftone reproductions found in [Smith's book] Clement of Alexandria and a Secret Gospel of Mark" where the images were printed with a line screen made of dots. If the "images are magnified to the degree necessary for forensic document examination" the dot matrix will be visible and the letters "will not appear smooth".[271] Once the printed images Carlson used are replaced with the original photographs, also the signs of tremors disappear.[270]

On the first York Christian Apocrypha Symposium on the Secret Gospel of Mark held in Canada in 2011, very little of Carlson's evidence was discussed.[w][272] Even Pierluigi Piovanelli – who thinks Smith committed a sophisticated forgery[273] – writes that the fact that "the majority of Carlson's claims" have been convincingly dismissed by Brown and Pantuck[274] and that no "clearly identifiable 'joke'" is embedded within the letter, "tend to militate against Carlson's overly simplistic hypothesis of a hoax."[275]

The Secret Gospel of Mark Unveiled

v The Secret Gospel of Mark Unveiled (2007),[276] Peter Jeffery argued that "the letter reflected practices and theories of the twentieth century, not the second",[241] and that Smith wrote Clement's letter to Theodore with the purpose of creating "the impression that Jesus practiced homosexualita ".[277] Jeffery reads the Secret Mark story as an extended dvojitý účastník that tells "a tale of 'sexual preference' that could only have been told by a twentieth-century Western author"[278] who inhabited "a homoerotic subculture in English universities".[279][280] Jeffery's thesis has been contested by, for example, Scott G. Brown[281] a William V. Harris. Jeffery's two main arguments, those concerning liturgy and homoeroticism, are according to Harris unproductive and he writes that Jeffery "confuses the question of the authenticity of the text and the validity of Smith's interpretations" by attacking Smith and his interpretation and not Secret Mark.[282] The homoerotic argument, according to which Smith would have written the document to portray Jesus as practicing homosexuality, does not work either. In his two books on Secret Mark, Smith "gives barely six lines to the subject".[282] Jeffery's conclusion that the document is a forgery "because no young Judaean man" would approach "an older man for sex" is according to Harris also invalid, since there is "no such statement" in Secret Mark.[282]

Smith's correspondence

In 2008, extensive correspondence between Smith and his teacher and lifelong friend Gershom Scholem was published, where they for decades discuss Clement's letter to Theodore and Secret Mark.[283] The book's editor, Guy Stroumsa, argues that the "correspondence should provide sufficient evidence of his [i.e., Smith's] intellectual honesty to anyone armed with common sense and lacking malice."[44] He thinks it shows "Smith's honesty",[284] and that Smith could not have forged the Clement letter, for, in the words of Anthony Grafton, the "letters show him discussing the material with Scholem, over time, in ways that clearly reflect a process of discovery and reflection."[285][286] Pierluigi Piovanelli has however contested Stroumsa's interpretation. He believes that the correspondence shows that Smith created an "extremely sophisticated forgery" to promote ideas he already held about Jesus as a magician.[273] Jonathan Klawans does not find the letters to be sufficiently revealing, and on methodological grounds, he thinks that letters written by Smith cannot give a definite answer to the question of authenticity.[287]

Smith's beforehand knowledge

A number of scholars have argued that the salient elements of Secret Mark were themes of interest to Smith which he had studied before the discovery of the letter in 1958.[X][291] In other words, Smith would have forged a letter that supported ideas he already embraced.[292] Pierluigi Piovanelli is suspicious about the letter's authenticity as he thinks it is "the wrong document, at the wrong place, discovered by the wrong person, who was, moreover, in need of exactly that kind of new evidence to promote new, unconventional ideas".[293] Craig Evans argues that Smith before the discovery had published three studies, in 1951,[294] 1955[295] and 1958,[296] in which he discussed and linked "(1) "the mystery of the kingdom of God" in Mark 4:11, (2) secrecy and initiation, (3) forbidden sexual, including homosexual, relationships and (4) Clement of Alexandria".[297]

This hypothesis has been contested mainly by Brown and Pantuck. First, they reject the idea that something sexual is even said to take place between Jesus and the young man in Secret Mark,[298][299] and if that is the case, then there are no forbidden sexual relations in the Secret Mark story. Second, they challenge the idea that Smith made the links Evans and others claim he did. They argue that Smith, in his doctoral dissertation from 1951,[294] did not link more than two of the elements – the mystery of the kingdom of God to secret teachings. Forbidden sexual relations, such as "incest, intercourse during menstruation, adultery, homosexuality, and bestiality", is just one subject among several others in the scriptures that the Tannaim deemed should be discussed in secret.[300][301] Further, they claim that Smith in his 1955 article[295] also only linked the mystery of the kingdom of God to secret teachings.[302] And in the third example, an article Smith wrote in 1958,[296] he only "mentioned Clement and his Stromateis as examples of secret teaching".[303][304] Brown and Pantuck consider it to be common knowledge among scholars of Christianity and Judaism that Clement and Mark 4:11 deal with secret teaching.[303]

Handwriting experts and Smith's ability

The November/December 2009 issue of Biblická archeologická recenze (BAR 35:06) features a selection of articles dedicated to the Secret Gospel of Mark. Charles W. Hedrick wrote an introduction to the subject,[51] a obojí Hershel Shanks[305] a Helmut Koester[306] wrote articles in support of the letter's authenticity. Since the three pro-forgery scholars who were contacted declined to participate,[y] Shanks had to make the argument for forgery himself.[307] Helmut Koester writes that Morton Smith "was not a good form-critical scholar" and that it "would have been completely beyond his ability to forge a text that, in terms of form-criticism, is a perfect older form of the same story as appears in Jan 11 as the raising of Lazarus."[308] In 1963 Koester and Smith met several hours a day for a week to discuss Secret Mark. Koester then realized that Smith really struggled to understand the text and to decipher the handwriting. Koester writes: "Obviously, a forger would not have had the problems that Morton was struggling with. Or Morton Smith was an accomplished actor and I a complete fool."[308]

In late 2009, Biblická archeologická recenze commissioned two Greek handwriting experts to evaluate "whether the handwriting of the Clement letter is in an authentic 18th-century Greek script" and whether Morton Smith could have written it.[z] They had at their disposal high-resolution scans of the photographs of the Clement letter and known samples of Morton Smith's English and Greek handwriting from 1951 to 1984.[309]

Venetia Anastasopoulou, a questioned document examiner a znalec with experience in many Greek court cases,[aa] noticed three very different writings. Clement's letter, in her opinion, was written skillfully with "freedom, spontaneity and artistic flair" by a trained scribe who could effectively express his thoughts.[310] Likewise, was Smith's English writing done "spontaneous and unconstrained, with a very good rhythm."[311] Smith's Greek writing, though, was "like that of a school student" who is unfamiliarized in Greek writing and unable "to use it freely" with ease.[312] Anastasopoulou concluded that in her professional opinion, Morton Smith with high probability could not have produced the handwriting of the Clement letter.[313] She further explained, contrary to Carlson's assertion, that the letter did not have any of the typical signs of forgery, such as "lack of natural variations" appearing to be drawn or having "poor line quality", and that when a large document, such as this letter by Clement, is consistent throughout, "we have a first indication of genuineness".[ab]

However, Agamemnon Tselikas, a distinguished Greek paleograf[ac] and thus a specialist in deciding when a particular text was written and in what school this way of writing was taught, thought the letter was a forgery. He noticed some letters with "completely foreign or strange and irregular forms". Contrary to Anastasopoulou's judgment, he thought some lines were non-continuous and that the hand of the scribe was not moving spontaneously.[inzerát] He stated that the handwriting of the letter is an imitation of eighteenth-century Greek script and that the most likely forger was either Smith or someone in Smith's employ.[2] Tselikas suggests that Smith, as a model for the handwriting, could have used four eighteenth-century manuscripts from the Thematon monastery he visited in 1951.[ae][314] Allan Pantuck could though demonstrate that Smith never took any photographs of these manuscripts and could consequently not have used them as models.[315][316] Since, according to Anastasopoulou's conclusion, the letter is written by a trained scribe with a skill that surpasses Smith's ability, in the words of Michael Kok, "the conspiracy theory must grow to include an accomplice with training in eighteenth-century Greek paleography".[317]

Having surveyed the archives of Smith's papers and correspondence, Allan Pantuck comes to the conclusion that Smith was not capable of forging the letter; that his Greek was not good enough to compose a letter in Clement's thought and style and that he lacked the skills needed to imitate a difficult Greek 18th-century handwriting.[318] Roy Kotansky, who worked with Smith on translating Greek, says that although Smith's Greek was very good, it "was not that of a true papyrologist (or philologist)". According to Kotansky, Smith "certainly could not have produced either the Greek cursive script of the Mar Saba manuscript, nor its grammatical text" and writes that few are "up to this sort of task";[319] which, if the letter is forged, would be "one of the greatest works of scholarship of the twentieth century", according to Bart Ehrman.[af]

Scott G. Brown and Eckhard Rau argue that Smith's interpretation of the longer passage from Secret Mark cannot be reconciled with its content,[320][321] and Rau thinks that if Smith really would have forged the letter, he should have been able to make it more suitable for his own theories.[320] Michael Kok thinks that the "Achillova pata of the forgery hypothesis" is that Smith seemingly did not have the necessary skills to forge the letter.[322]

Výklad

Smith's theories about the historical Jesus

Smith thought that the scene in which Jesus taught the young man "the mystery of the kingdom of God" at night, depicted an initiation rite of baptism[G] which Jesus offered his closest disciples.[323][324] In this baptismal rite "the initiate united with Jesus' spirit" in a hallucinatory experience, and then they "ascended mystically to the heavens." The disciple would be set free from the Mosaic Law and they would both become libertines.[325] The libertinismus of Jesus was then later suppressed by James, the brother of Jesus, a Pavel.[117][326] The idea that "Jesus was a libertine who performed a hypnotic rite of" illusory ascent to the heavens,[327][328] not only seemed far-fetched but also upset many scholars,[327][329] who could not envision that Jesus would be portrayed in such a way in a trustworthy ancient text.[330] Scott Brown argues though that Smith's usage of the term libertine did not mean sexual libertinism, but freethinking in matters of religion, and that it refers to Jews and Christians who chose not to keep the Mosaic Law.[325] In each of his books on Secret Mark, Smith made one passing suggestion that Jesus and the disciples might have united also physically in this rite,[331][332] but he thought that the essential thing was that the disciples were possessed by Jesus' spirit".[h] Smith acknowledged that there is no way to know if this libertinism can be traced as far back as Jesus.[333][i]

In his later work, Morton Smith increasingly came to see the historical Jesus as practicing some type of magical rituals and hypnotism,[26][68] thus explaining various healings of demoniacs in the gospels.[335] Smith carefully explored for any traces of a "libertine tradition" in early Christianity and in the New Testament.[336][337] Yet there's very little in the Mar Saba manuscript to give backing to any of this. This is illustrated by the fact that in his later book, Jesus the Magician, Smith devoted only 12 lines to the Mar Saba manuscript,[338] and never suggested "that Jesus engaged in sexual libertinism".[339]

Lacunae and continuity

The two excerpts from Secret Mark suggest resolutions to some puzzling passages in the canonical Mark.

The young man in the linen cloth

In Mark 14:51–52, a young man (řecký: νεανίσκος, neaniskos ) in a linen cloth (řecký: σινδόνα, sindona) is seized during Jesus' arrest, but he escapes at the cost of his clothing.[340] This passage seems to have little to do with the rest of the narrative, and it has given cause to various interpretations. Sometimes it is suggested that the young man is Mark himself.[341][342][ag] However, the same Greek words (neaniskos a sindona) are also used in Secret Mark. Několik vědců, jako např Robert Grant a Robert Gundry, suggest that Secret Mark was created based on Mark 14:51, 16:5 and other passages and that this would explain the similarities.[j] Other scholars, such as Helmut Koester[174] a J. D. Crossan,[347] argue that the canonical Mark is a revision of Secret Mark. Koester thinks that an original Proto-Mark was expanded with, among other things, the raising of the youth in Secret Mark and the fleeing naked youth during Jesus' arrest in Mark 14:51–52, and that this gospel version later was abridged to form the canonical Mark.[36] According to Crossan, Secret Mark was the original gospel. In the creation of canonical Mark, the two Secret Mark passages quoted by Clement were removed and then dismembered and scattered throughout canonical Mark to form the neaniskos-passages.[348] Miles Fowler and others argue that Secret Mark originally told a coherent story, including that of a young man. From this gospel, some passages were removed (by the original author or by someone else) to form canonical Mark. In this process, some remnants were left, such as that of the fleeing naked young man, while other passages may have been completely lost.[38][176][349]

Marvin Meyer sees the young man in Secret Mark as a paradigmatic disciple that "functions as a literary rather than a historical figure."[350] The young man (neaniskos) wears only "a linen cloth" (sindona) "over his naked body".[19] This is reminiscent of Mark 14:51–52, where, in the garden of Gethsemane, an unnamed young man (neaniskos) who is wearing nothing but a linen cloth (sindona) about his body is said to follow Jesus, and as they seize him, he runs away naked, leaving his linen cloth behind.[351] Slovo sindōn is also found in Mark 15:46 where it refers to Jesus' burial wrapping.[352][353] And in Mark 16:5 a neaniskos (young man) in a white robe, who in Mark does not seem to function as an angel,[ah] is sitting in the empty tomb when the women arrive to anoint Jesus' body.[38][354]

Miles Fowler suggests that the naked fleeing youth in Mark 14:51–52, the youth in the tomb of Jesus in Mark 16:5 and the youth Jesus raises from the dead in Secret Mark are the same youth; but that he also appears as the rich (and in the parallel account in Matthew 19:20, "young") man in Mark 10:17–22, whom Jesus loves and urges to give all his possessions to the poor and join him.[38] This young man is furthermore by some scholars identified as both Lazarus (due to the similarities between Secret Mark 1 and John 11) and the beloved disciple (due to the fact that Jesus in Secret Mark 2 is said to have loved the youth, and that in the gospels he is said to have loved only the three siblings Martha, Mary a Lazar (Joh 11:5), the rich man (Mark 10:22) and the beloved disciple ).[ai][356] Hans-Martin Schenke interprets the scene of the fleeing youth in Gethsemane (Mark 14:51–52) as a symbolic story in which the youth is not human but rather a shadow, a symbol, an ideal disciple. He sees the reappearing youth as a spiritual double of Jesus and the stripping of the body as a symbol of the soul being naked.[357]

Marvin Meyer finds a subplot, or scenes or vignettes, "in Secret Mark that is present in only a truncated form in canonical Mark", about a young man as a symbol of discipleship who follows Jesus throughout the gospel story.[358]).[359] The first trace of this young man is found in the story of the rich man in Mark 10:17–22 whom Jesus loves and "who is a candidate for discipleship"; the second is the story of the young man in the first Secret Mark passage (after Mark 10:34) whom Jesus raises from the dead and teaches the mystery of the kingdom of God and who loves Jesus; the third is found in the second Secret Mark passage (at Mark 10:46) in which Jesus rejects Salome and the sister of the youth whom Jesus loved and his mother; the fourth is in the story of the escaping naked young man in Gethsemane (Mark 14:51–52); and the fifth is found in the story of the young man in a white robe inside the empty tomb, a youth who informs Salome and the other women that Jesus has risen (Mark 16:1–8).[360] In this scenario, a once-coherent story in Secret Mark would, after much of the elements had been removed, form an incoherent story in canonical Mark with only embedded echoes of the story present.[38]

Lacuna in the trip to Jericho

The second excerpt from Secret Mark fills in an apparent mezera in Mark 10:46: "They came to Jericho. As he and his disciples and a large crowd were leaving Jericho, Bartimaeus son of Timaeus, a blind beggar, was sitting by the roadside."[361][362] Morton Smith notes that "one of Mark's favorite formulas" is to say that Jesus comes to a certain place, but "in all of these except Mark 3:20 and 10:46 it is followed by an account of some event which occurred in the place entered" before he leaves the place.[363] Due to this apparent gap in the story, there has been speculation that the information about what happened in Jericho has been omitted.[361][364] Podle Robert Gundry, the fact that Jesus cures the blind Bartimaeus on the way from Jericho justifies that Mark said that Jesus came to Jericho without saying that he did anything there. As a parallel, Gundry refers to Mark 7:31 where Jesus "returned from the region of Pneumatika, and went by way of Sidone směrem k Galilejské moře ".[365] However, here Jesus is never said to have entered Sidon, and it is possible that this is an amalgamation of several introductory notices.[366]

With the addition from Secret Mark, the gap in the story would be solved: "They came to Jericho, and the sister of the youth whom Jesus loved and his mother and Salome were there, and Jesus did not receive them. As he and his disciples and a large crowd were leaving Jericho ..."[367] The fact that the text becomes more comprehensible with the addition from Secret Mark,[39] plus the fact that Salome is mentioned (and since she was "popular in heretical circles", the sentence could have been abbreviated for that reason), indicates that Secret Mark has preserved a reading that was deleted in the canonical Gospel of Mark.[368] Crossan thinks this shows that "Mark 10:46 is a condensed and dependent version of" the Secret Mark sentence.[369] Others argue that it would be expected that someone later would want to fill in the obvious gaps that occur in the Gospel of Mark.[370]

Relation to the Gospel of John

The raising of Lazarus in John and the young man in Secret Mark

The resurrection of the young man by Jesus in Secret Mark bears such clear similarities to the raising of Lazarus in the Gospel of John (11:1–44) that it can be seen as another version of that story.[371] But although there are striking parallels between these two stories,[38] there are also "numerous, often pointless, contradictions."[372] If the two verses in Mark preceding Secret Mark are included, both stories tell us that the disciples are apprehensive as they fear Jesus' arrest. In each story it is the sister whose brother just died who approaches Jesus on the road and asks his help; she shows Jesus the tomb, which is in Bethany; the stone is removed, and Jesus raises the dead man who then comes out of the tomb.[373] In each story, the emphasis is upon the love between Jesus and this man,[24] and eventually, Jesus follows him to his home.[38] Each story occurs "at the same period in Jesus' career", as he has left Galilee and gone into Judea and then to Transjordánsko.[374][375]

Jesus' route in Mark

With the quoted Secret Mark passages added to the Gospel of Mark, a story emerges in which Jesus on his way to Jeruzalém listy Galilee and walks into northernJudea, then crosses the Jordan River east into Peraea and walks south through Peraea on the eastern side of the Jordan, meets the rich man whom he urges to give all his possessions to the poor and follow him (Mark 10:17–22), comes to Bethany, still on the other side of Jordan, and raises the young man from the dead (Secret Mark 1). He then crosses the river Jordan again and continues west while rejecting James' and John's request (Mark 10:35–45). He arrives at Jericho where he does not receive the three women (Mark 10:46 + Secret Mark 2) and then leaves Jericho to meet the blind Bartimaeus and give him back his sight.[376][377]

Two Bethanys

In each story, the raising of the dead man takes place in Bethany.[378] In the Gospel of John (10:40) Jesus is at "the place where John had been baptizing", which in John 1:28 is said to be a place named "Bethany beyond the Jordan " when Mary arrives and tells him that Lazarus is sick (John 11:1–3). Jesus follows her to another village called Bethany just outside of Jerusalem (John 11:17–18). In Secret Mark, the woman meets him at the same place, but he never travels to Bethany near Jerusalem. Instead, he just follows her to the young man since he already is in Bethany (beyond the Jordan).[379] In Secret Mark, the young man (Lazarus?) and his sister (Mary?) are not named, and their sister Martha does not even appear.[371][380]

Relations between the gospels

A number of scholars argue that the story in Secret Mark is based on the Gospel of John.[aj] Other scholars argue that the authors of Secret Mark and the Gospel of John independently used a common source or built on a common tradition.[24] The fact that Secret Mark refers to another Bethany than the one in the Gospel of John as the place for the miracle and omits the names of the protagonisté, and since there are no traces in Secret Mark of the rather extensive Johannine redaction,[24] or of other Johannine characteristics, including its language, militate against Secret Mark being based on the Gospel of John.[372][384][385][386] Michael Kok thinks that this also militates against the thesis that the Gospel of John depends on Secret Mark and that it indicates that they both are based either on "oral variants of the same underlying tradition",[387] or on older written collections of miracle stories.[24] Koester thinks Secret Mark represents an earlier stage of development of the story.[24] Morton Smith tried to demonstrate that the resurrection story in Secret Mark does not contain any of the secondary traits found in the parallel story in John 11 and that the story in John 11 is more theologically developed. He concluded that the Secret Mark version of the story contains an older, independent, and more reliable witness to the ústní tradice.[115][388][386]

Baptismal significance

Morton Smith saw the longer Secret Mark passage as a story of baptism.[G][391] According to Smith "the mystery of the kingdom of God" that Jesus taught the young man, was, in fact, a magical rite that "involved a purificatory baptism".[392][324] That this story depicts a baptism was in turn accepted by most scholars, also those otherwise critical to Smith's reconstructions.[391][393][394] And with the idea of the linen sheet as a baptismal garment followed the idea of nakedness and sex.[395]

But there has been some debate about this matter. Například, Scott G. Brown (while defending the authenticity of Secret Mark) disagrees with Smith that the scene is a reference to baptism. He thinks this is to profoundly misinterpret the text,[393] and he argues that if the story really had been about baptism, it would not have mentioned only teaching, but also water or disrobing and immersion.[391][396] He adds that "the young man's linen sheet has baptismal connotations, but the text discourages every attempt to perceive Jesus literally baptizing him."[397] Stephen Carlson agrees that Brown's reading is more plausible than Smith's.[398] The idea that Jesus practiced baptism is absent from the Synoptic Gospels, though it is introduced in the Janovo evangelium.[ak][365]

Brown argues that Clement, with the expression "the mystery of the kingdom of God,"[19] primarily meant "advanced theological instruction."[al] On the other three occasions when Clement refers to "initiation in the great mysteries",[dopoledne] he always refers to the "highest stage of Christian theological education, two stages beyond baptism" – a philosophical, intellectual and spiritual experience "beyond the material realm".[401] Brown thinks the story of the young man is best understood symbolically, and the young man is best seen as an abstract symbol of "discipleship as a process of following Jesus in the way to life through death".[402]These matters also have a bearing on the debates about the authenticity of Secret Mark, because Brown implies that Smith, himself, did not quite understand his own discovery and it would be illogical to forge a text that you do not understand, to prove a theory it does not support.[an]

Viz také

Poznámky a odkazy

Poznámky

- ^ Agamemnon Tselikas, "Grammatical and Syntactic Comments"[2]

- ^ A b C Isaac Vossius ' first edition of the letters of Ignáce z Antiochie published in Amsterdam in 1646.[6] The book was catalogued by Morton Smith as MS 65.[7]

- ^ Smith, Morton, Manuscript Material from the Monastery of Mar Saba: Discovered, Transcribed, and Translated by Morton Smith, New York, privately published (Dec. 1958), pp. i + 10. It "was submitted to the U.S. Copyright Office on December 22, 1958."[54]

- ^ The meeting took place on December 29, 1960, in "the Horace Mann Auditorium, Teacher's College" at Columbia University.[62]

- ^ The Greek adjective "mystikon" (μυστικόν) has two basic meanings, "secret" and "mystic". Morton Smith chose to translate it to "secret",[101] which gives the impression that the gospel was concealed. Scott Brown translates it to "mystic", i.e. a gospel that has concealed meanings.[4]

- ^ For instance, were many apocryphal texts first encountered in and published from a single late manuscript, like the Počáteční Thomasovo evangelium a Infancy Gospel of James.[31] In 1934 the previously unknown Egerton Gospel was purchased from an antique dealer in Egypt.[109]

- ^ A b C Smith got the idea that the gospel story depicts a rite of baptism from Cyril Richardson in January 1961.[389][390]

- ^ A b "'the mystery of the kingdom of God' ... was a baptism administered by Jesus to chosen disciples, singly, and by night. In this baptism the disciple was united with Jesus. The union may have been physical (... there is no telling how far symbolism went in Jesus' rite), but the essential thing was that the disciple was possessed by Jesus' spirit."[324]

- ^ A b "the disciple was possessed by Jesus' spirit and so united with Jesus. One with him, he participated by hallucination in Jesus' ascent into the heavens ... Freedom from the law may have resulted in completion of the spiritual union by physical union ... how early it began there is no telling."[334]

- ^ A b Robert Grant thinks the author took everything about the young man (řecký: neaniskos) from the canonical gospels (Mark 14:51–52, 16:5; Matt 19:20 & 22, Luke 7:14);[344] so also Robert Gundry (Mark 10:17–22, Matt 19:16–22, Luke 18:18–23).[345][346]

- ^ Smith wrote that the tower library alone (there were two libraries) must have had at least twice the number of books as were listed in the 1910 catalogue,[137] and he estimated them to between 400 and 500.[138] Smith's preserved notes on the Mar Saba books end with item 489.[143]

- ^ Eyer refers to Fitzmyer, Joseph A. "How to Exploit a Secret Gospel." Amerika 128 (23 June 1973), pp. 570–572 and Gibbs, John G., review of Secret Gospel, Teologie dnes 30 (1974), pp. 423–426.[68]

- ^ V Sacra Parallela, normally attributed to John of Damascus, a citation from Clement is introduced with: "From the twenty-first letter of Clement the Stromatist".[157] Opposite the view of later biographer, some modern scholars have argued that John of Damascus lived and worked mainly in Jerusalem until 742.[158]

- ^ Beskow, Per (1979), Fynd och fusk i Bibelns värld: om vår tids Jesus-apokryfer, Stockholm: Proprius, ISBN 9171183302

- ^ Smith napočítal 25 vědců, kteří si mysleli, že Clement napsal dopis, 6 těch, kteří neposkytli stanovisko, a 4, kteří nesouhlasili. 15 učenců si myslelo, že tajný materiál byl vytvořen z kanonických evangelií a 11 si myslelo, že tento materiál existoval před napsáním Markova evangelia.[172]

- ^ Tajná značka na „raně křesťanských spisech“,[173] včetně citací Helmuta Koestera,[174] a Ron Cameron.[175]

- ^ „Předpoklad zachování posledních komentářů [Donalda] Akenson a [Jacob] Neusner je to Dopis Theodorovi je zřejmé padělání. Pokud by tomu tak bylo, neměli by mít problém poskytnout definitivní důkaz, ale oba se této odpovědnosti vyhnuli tím, že označili dokument za zjevně podvodný, takže důkaz by byl nadbytečný. “[186]

- ^ „Ale ti, kdo tvrdí, že dopis je padělek dvacátého století, musí nyní připustit, aby padělatel měl kromě dříve uznávaných kompetencí také solidní znalosti o epiztolografii, starodávných postupech kompozice a přenosu a schopnosti vázat dopis s jemnou obecnou strukturou. v patristice, řecké paleografii z 18. století, Markanových literárních technikách a ohromném vhledu do psychologie a umění podvodu. “[191]

- ^ Scott G. Brown hovoří o Ronaldovi Thistedovi a Bradleym Efronovi, kteří tvrdí, že „neexistuje stálý trend směrem k přebytku nebo nedostatku nových slov“.[198][196]

- ^ „Vím, že fakta zřídka stojí v cestě neuvěřitelné teorii, ale myslel bych si, že každý, kdo si dokáže představit, že Smith vytvořil perfektní padělek, by měl alespoň potíže představit si ho, jak čte antiintelektuální evangelický křesťanský špionážní román.[207]

- ^ Sanka Knox, „Nové evangelium připisované Markovi; kopie řeckého dopisu říká, že svatý uchovával„ tajemství “NA TAJNÉM GOSPELU PŘIHLÁŠENÉ K OZNAČENÍ“. New York Times, 30. prosince 1960.

- ^ Birger A. Pearson byl Carlsonem přesvědčen, že Smith text zfalšoval.[256]

- ^ Tony Burke: Apocryphicity - "Ancient Gospel or Modern Forgery? The Secret Gospel of Mark in Debate". York University Christian Apocrypha Symposium Series 2011, 29. dubna 2011, York University (Vanier College). Úvahy o sympoziu Secret Mark, část 2

- ^ Především Quentin Quesnell,[288] Stephen C. Carlson,[289] Francis Watson[290] a Craig A. Evans.[205]

- ^ Těmito třemi vědci, kteří se zabývali falšováním, byl Stephen C. Carlson, Birger A. Pearson a Bart D Ehrman.[307]

- ^ Biblická archeologická recenze, „Zformoval Morton Smith‚ tajnou značku '? “

- ^ „Expert na rukopis váží autentičnost„ tajné značky ““ dostupný online Archivováno 2010-07-05 na Wayback Machine (datum přístupu 15. dubna 2018).

- ^ Venetia Anastasopoulou: „Může dokument sám o sobě odhalit padělek?“ dostupný online (datum přístupu 1. května 2018).

- ^ "Dr. Tselikas je ředitelem Centra pro historii a paleografii Kulturní nadace Řecké národní banky a také Středomořský výzkumný ústav pro paleografii, bibliografii a historii textů. “[2]

- ^ Agamemnon Tselikas, „Paleografická pozorování 1“[2]

- ^ Agamemnon Tselikas, "Textologická pozorování"[2]

- ^ „Je pravda, že moderní padělek by byl úžasný výkon. Aby to bylo možné sfalšovat, musel by někdo napodobovat řecký styl rukopisu z 18. století a vytvořit dokument, který se tolik podobá Clementovi, že oklamá odborníky, kteří tráví svůj život analyzováním Clementa, který cituje dříve ztracenou pasáž Marka, která je natolik podobná Markovi, že oklamá odborníky, kteří tráví svůj život analyzováním Marka. Pokud je to padělané, je to jedno z největších vědeckých děl dvacátého století, někdo, kdo do toho vložil neskutečné množství práce. “[94]

- ^ Někteří komentátoři se domnívají, že chlapec byl cizinec, který žil poblíž zahrady a po probuzení vyběhl napůl oblečený, aby zjistil, o čem je ten hluk (v. 46–49) (Viz John Gill Expozice Bible, at Nástroje pro studium Bible.) W. L. Lane si myslí, že Mark zmínil tuto epizodu, aby dal jasně najevo, že nejen učedníci, ale „Všechno uprchl a nechal Ježíše samotného ve vazbě policie. “[343]

- ^ V paralelních pasážích u Matouše a Lukáše slovo neaniskos se nepoužívá. U Matouše 28: 2 je to „anděl Páně“ oblečený v bílém, který sestupuje z nebe a „Lukáš předpokládá dva andělské muže“ (Lukáš 24: 1–10).[354]

- ^ Výraz „učedník, kterého Ježíš miloval“ (řecky: ὁ μαθητὴς ὃν ἠγάπα ὁ Ἰησοῦς, ho mathētēs hon ēgapa ho Iēsous) nebo „milovaný žák“, žák „milovaný Ježíše“ (Řek: ὃν ἐφίλει ὁ Ἰησοῦς, hon efilei ho Iēsous) je zmíněn pouze v Janově evangeliu, a to v šesti pasážích: 13:23, 19:26, 20: 2, 21: 7, 21:20, 21:24.[355]

- ^ Například F. F. Bruce,[381] Raymond E. Brown,[382] Patrick W. Skehan,[120] Robert M. Grant,[123] Helmut Merkelová,[383][117] a Frans Neirynck.[126]

- ^ Ježíš říká, že křtil své následovníky v Janovi 3:22: „... strávil tam s nimi nějaký čas a křtil“; Jan 3:26: „... křtí a všichni jdou k němu“; a Jan 4: 1: „Ježíš činí a křtí více učedníků než Jan“. Ale v následujícím verši (Jan 4: 2) si evangelium odporuje: „- ačkoli to nebyl Ježíš sám, ale jeho učedníci, kteří křtili -“ (NRSV).[399]

- ^ „... publikem delšího evangelia nejsou katechumeni, kteří se připravují na křest, ale pokřtění křesťané zapojení do pokročilé teologické výuky, jejímž cílem je gnóza.“[400]

- ^ Klement Alexandrijský, Stromata I.28.176.1–2; IV.1.3.1; V.11.70.7–71.3.[401]

- ^ „Jazyk tajemného náboženství v dopise je metaforický, stejně jako v nesporných spisech Clementa, a křestní obrazy v evangeliu jsou symbolické, jak se na„ mystické evangelium “hodí. Smith bohužel tuto metaforu interpretoval doslovně, když popisoval text používaný jako přednáška ke křtu. “[403]

Reference

- ^ Schenke 2012, str. 554.

- ^ A b C d E Tselikas 2011

- ^ Burnet 2013, str. 290.

- ^ A b C Brown 2005, str. xi.

- ^ Smith 1973, str. 93–94.

- ^ A b Ignáce 1646

- ^ A b C Pantuck & Brown 2008, s. 107–108.

- ^ A b Smith 1973, str. 1.

- ^ A b Smith 1973b, str. 13.

- ^ A b C d E F Brown 2005, str. 6.

- ^ Burke 2013, str. 2.

- ^ A b C Burke 2013, str. 5.

- ^ Watson 2010, str. 128.

- ^ A b C d E F Brown 2005, s. 25–26.

- ^ A b C Hedrick a Olympiou 2000, s. 8–9.

- ^ A b Hedrick 2013, str. 42–43.

- ^ Hedrick 2009, str. 45.

- ^ A b Rau 2010, str. 142.

- ^ A b C d E F G h i Smith 2011

- ^ Brown 2017, str. 95.

- ^ A b Hedrick 2003, str. 133.

- ^ Grafton 2009, str. 25.

- ^ A b Meyer 2003, str. 139.

- ^ A b C d E F G Koester 1990, str. 296.

- ^ A b C Theissen & Merz 1998, str. 46.

- ^ A b C Grafton 2009, str. 26.

- ^ A b Brown 2005, str. 68.

- ^ A b C Hedrick 2003, str. 141.

- ^ Carlson 2013, str. 306–307.

- ^ A b C d Ehrman 2003, str. 81–82.

- ^ A b C d Burke 2013, str. 27.

- ^ A b C d Hedrick 2013, str. 31.

- ^ A b C Smith 1982, str. 457.

- ^ A b C d E F G h Burke 2013, str. 6.

- ^ Hedrick 2013, str. 44.

- ^ A b C d E Burke 2013, str. 9.

- ^ Burke 2013, str. 22.

- ^ A b C d E F G h Fowler 1998

- ^ A b Ehrman 2003, str. 79.

- ^ Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 354.

- ^ Hedrick 2003, str. 144.

- ^ Meyer 2010, str. 75.

- ^ A b Smith 1973b, str. 9.

- ^ A b Stroumsa 2008, str. xv.

- ^ Pantuck & Brown 2008, s. 106–107, n. 1.

- ^ Hedrick 2009, str. 44.

- ^ Pantuck & Brown 2008, str. 106.

- ^ A b Criddle 1995

- ^ Huller & Gullotta 2017

- ^ Piovanelli 2013

- ^ A b Hedrick 2009

- ^ Watson 2010

- ^ Ehrman 2003c

- ^ Pantuck & Brown 2008, str. 108, č. 5.

- ^ Pantuck 2013, str. 204.

- ^ A b Pantuck 2013, str. 203.

- ^ Pantuck 2013, str. 207.

- ^ Smith 1973b, s. 25–27.

- ^ Smith 1973b, s. 22–25.

- ^ Kok 2015, str. 273.

- ^ Smith 1973b, str. 30.

- ^ Brown 2013, str. 247.

- ^ A b C Smith 1973

- ^ Smith 1973b, str. 76.

- ^ Smith 1973, str. 445–454, desky I – III.

- ^ A b Smith 1973b

- ^ Hedrick 2003, str. 135.

- ^ A b C Eyer 1995

- ^ Šipka 2003, str. 137.

- ^ Stroumsa 2003, str. 147.

- ^ A b C d Stroumsa 2003, str. 147–148.

- ^ A b C Hedrick 2009, str. 48.

- ^ Stroumsa 2008, str. xx – xxi.

- ^ Šipka 2003, str. 138.

- ^ A b Hedrick 2003, str. 140.

- ^ Hedrick a Olympiou 2000, s. 9–10.

- ^ A b C d E Burke 2013, str. 11.

- ^ Hedrick 2003, str. 136.

- ^ Hedrick a Olympiou 2000, str. 8.

- ^ Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 353–354, 362, 364.

- ^ Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 369–370, 374–376.

- ^ A b C Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 369.

- ^ Quesnell 1975, str. 49–50.

- ^ Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 357–358.

- ^ A b Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 362–363.

- ^ A b Hedrick a Olympiou 2000, s. 11–15.

- ^ Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 377.

- ^ Collins & Attridge 2007, str. 491.

- ^ Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 353.

- ^ A b Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 371–375, 378.

- ^ Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 365.

- ^ Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 375.

- ^ Paananen 2019, str. 19.

- ^ A b C d Ehrman 2003, str. 82.

- ^ Anastasopoulou 2010, str. 4.

- ^ A b C Hedrick 2009, str. 46.

- ^ Ehrman 2003b, str. 161.

- ^ Evans 2013, str. 87.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 3–5.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 121–122.

- ^ A b Smith 1973, str. 24.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 123.

- ^ Cameron 1982, str. 67.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. xxi.

- ^ Smith 1973b, str. 18.

- ^ Ehrman 2003, str. 85.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 69–70.

- ^ A b Evans 2013, str. 99.

- ^ A b Kok 2015, str. 271.

- ^ Smith 2005, str. 1.

- ^ Burke 2013, str. 21.

- ^ Hedrick a Olympiou 2000, str. 3.

- ^ Merkelová 1991, str. 106–107.

- ^ Smith 1982, str. 452.

- ^ A b Brown 2005, str. 7.

- ^ A b Hedrick 2003, str. 135.

- ^ A b C d E Merkelová 1991, str. 107.

- ^ Bruce 1974, str. 20.

- ^ Brown 1974 474, 485.

- ^ A b Skehan 1974, str. 452.

- ^ Udělit 1974, str. 58.

- ^ Udělit 1974, str. 60–61.

- ^ A b Udělit 1974

- ^ Merkelová 1974, s. 130–136.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 10.

- ^ A b Neirynck 1979

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 93.

- ^ Wright 1996, str. 49.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 11.

- ^ Quesnell 1975, str. 48–67.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 12.

- ^ Quesnell 1975, str. 56–58.

- ^ A b C Klement Alexandrijský 1905–1936

- ^ Quesnell 1975, str. 55, 63–64.

- ^ Crossan 1985, str. 100.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 35.

- ^ A b C Smith 1973, str. 290.

- ^ A b Smith 1960, str. 175.

- ^ Jeffery 2007, str. 39.

- ^ Carlson 2005, s. 36–37.

- ^ Quesnell 1975, str. 56.

- ^ Evans 2013, str. 97.

- ^ Pantuck & Brown 2008, str. 107, č. 2.

- ^ Pantuck & Brown 2008, str. 106–107.

- ^ Brown & Pantuck 2013, str. 131.

- ^ Murgia 1976, str. 35–40.

- ^ Murgia 1976, str. 40.

- ^ Ehrman 2003c, str. 161.

- ^ Murgia 1976, s. 38–39.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 30.

- ^ Klawans 2018, str. 495–496.

- ^ Brown 2005, s. 30–31.

- ^ A b C Smith 1982, str. 451.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 29.

- ^ Smith 1973b, str. 12.

- ^ Smith 1973b, s. 6, 285–286.

- ^ Watson 2010, str. 133–134.

- ^ Piovanelli 2013, s. 163.

- ^ Smith 1973, str. 289.

- ^ Smith 1973b, s. 143–148.

- ^ Brown 2005, s. 28–34.

- ^ Watson 2010, str. 129, n. 4.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 33.

- ^ Quesnell 1975

- ^ Smith 1976, str. 196.

- ^ Huller & Gullotta 2017, str. 359–360.

- ^ Beskow 1983

- ^ Pearson 2008, s. 6–7, 11.

- ^ A b C Beskow 2011, str. 460.

- ^ Pearson 2008, str. 7.

- ^ Smith 1982, str. 451–452.

- ^ Šipka 2003, str. 13.

- ^ Kirby 2005

- ^ A b Koester 1990, str. 293–303.

- ^ Cameron 1982, s. 67–71.

- ^ A b Schenke 2012, str. 554–572.

- ^ Crossan 1985, str. 108.

- ^ Meyer 2003, str. 118.

- ^ A b Meyer 2003

- ^ Kok 2015, str. 276.

- ^ Watson 2010, str. 129.

- ^ Henige 2009, str. 41.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 43–44.

- ^ Neusner 1993, str. 28.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 39.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 47.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 24.

- ^ Smith 1982, str. 450.

- ^ Jay 2008, str. 573.

- ^ Jay 2008, str. 596.

- ^ Jay 2008, str. 596–597.

- ^ Carlson 2005, str. 49.

- ^ Carlson 2005, str. 117, č. 3.

- ^ Criddle 1995, str. 218.

- ^ Brown 2016, str. 316–317.

- ^ A b Brown 2008, str. 536–537.

- ^ Brown 2016, str. 317.

- ^ Thisted & Efron 1987, str. 451.

- ^ Hunter 1940

- ^ Carlson 2005, s. 19–20.

- ^ Jenkins 2001, str. 101–102.

- ^ Burke 2013, str. 8.

- ^ Cena 2004, s. 127–132.

- ^ Watson 2010, s. 161–170.

- ^ A b Evans 2013, str. 75–100.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 58.

- ^ Brown 2005, str. 58–59.

- ^ Brown & Pantuck 2013, str. 104.

- ^ Watson 2010, str. 169.

- ^ Pantuck 2011a, s. 1–16.

- ^ Martínez 2016, str. 6.

- ^ Martínez 2016, s. 6–7.

- ^ Watson 2010, str. 170.

- ^ Martínez 2016, str. 7.

- ^ Evans 2013, str. 90.

- ^ Watson 2010, str. 165–170.

- ^ Paananen 2019, str. 60–62.

- ^ Šipka 2003

- ^ A b Schuler 2004

- ^ Carlson 2005, str. 124.

- ^ A b Ehrman 2003c, str. 158.

- ^ Ehrman 2003c, str. 159.

- ^ Ehrman 2003, str. 89.

- ^ Hedrick 2003, str. 134-136.