Squanto - Squanto

Tisquantum („Squanto“) | |

|---|---|

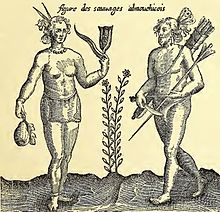

1911 ilustrace Tisquantum („Squanto“), které učí Plymouthští kolonisté zasadit kukuřici. | |

| narozený | C. 1585 |

| Zemřel | koncem listopadu 1622 OS Mamamoycke (nebo Monomoit) (Nyní Chatham, Massachusetts ) |

| Národnost | Patuxet |

| Známý jako | Poradenské, poradenské a překladatelské služby pro EU Mayflower osadníci |

Tisquantum (/tɪsˈkwɒnt.m/; C. 1585 (± 10 let?) - konec listopadu 1622 OS ), běžněji známý zdrobněnou variantou Squanto (/ˈskwɒntoʊ/), byl členem Kmen Patuxet nejlépe známý pro bytí časný styk mezi domorodým Američanem populace v Southern Nová Anglie a Mayflower Poutníci kteří se usadili na místě bývalé letní vesničky Tisquantum. Kmen Patuxetů žil na západním pobřeží ostrova Zátoka Cape Cod, ale byli vyhlazeni epidemickou infekcí.

Tisquantum byl unesen anglickým průzkumníkem Thomasem Huntem, který ho odnesl do Španělska, kde ho prodal ve městě Málaga. Byl mezi řadou zajatců koupených místními mnichy, kteří se zaměřili na jejich vzdělání a evangelizaci. Tisquantum nakonec odcestoval do Anglie, kde se možná setkal Pocahontas, domorodý Američan z Virginie, v letech 1616-1617.[1] Poté se v roce 1619 vrátil do Ameriky do své rodné vesnice, ale zjistil, že jeho kmen byl zničen epidemickou infekcí; Tisquantum byl poslední z Patuxetů.

The Mayflower přistál v zátoce Cape Cod v roce 1620 a Tisquantum pracoval na zprostředkování mírumilovných vztahů mezi poutníky a místními Pokanokets. Na prvních setkáních v březnu 1621 hrál klíčovou roli, částečně proto, že mluvil anglicky. Poté žil s Poutníky 20 měsíců a pracoval jako překladatel, průvodce a poradce. Seznámil osadníky s obchodem s kožešinami a naučil je setí a hnojení původních plodin; to se ukázalo jako životně důležité, protože semena, která poutníci přinesli z Anglie, většinou selhala. Jak se nedostatek potravin zhoršoval, Plymouthská kolonie Guvernér William Bradford spoléhal na Tisquantum, že pilotuje loď osadníků na obchodní expedici kolem Cape Cod a prostřednictvím nebezpečných hejn. Během této cesty Tisquantum uzavřel smlouvu, kterou Bradford nazval „indickou horečkou“. Bradford s ním zůstal několik dní, dokud nezemřel, což Bradford popsal jako „velkou ztrátu“.

Kolem Tisquanta vyrostla v průběhu času značná mytologie, a to především kvůli brzké chvále Bradforda a kvůli ústřední roli, kterou Díkůvzdání festival 1621 her v americké lidové historii. Tisquantum byl spíše praktickým poradcem a diplomatem než ušlechtilý divoch ten pozdější mýtus vylíčil.

název

Dokumenty ze 17. století různě vykreslují pravopis Tisquantova jména jako Tisquantum, Tasquantum, a Tusquantuma střídavě mu zavolat Squanto, Squantum, Tanta, a Tantam.[2] Dokonce i ti dva Mayflower osadníci, kteří s ním jednali, jeho jméno přesně vyhláskovali; Bradford ho přezdíval „Squanto“ Edward Winslow vždy o něm mluvil jako Tisquantum, což podle historiků bylo jeho vlastní jméno.[3] Jedním z návrhů významu je, že je odvozen z Algonquian výraz pro vztek Manitou, „světobsahující duchovní síla v srdci náboženských přesvědčení pobřežních indiánů“.[4] Manitou byla „duchovní síla předmětu“ nebo „fenomén“, síla, díky níž „všechno v přírodě reagovalo na člověka“.[5] Byly nabídnuty další návrhy,[A] ale všechny zahrnují určitý vztah k bytostem nebo mocnostem, které kolonisté spojovali s ďáblem nebo zlem.[b] Je tedy nepravděpodobné, že by to bylo jeho rodné jméno, spíše než rodné jméno, které získal nebo převzal později v životě, ale v tomto ohledu neexistují žádné historické důkazy. Jméno může napovídat například o tom, že prošel zvláštním duchovním a vojenským výcvikem, a proto byl v roce 1620 vybrán pro svou roli styku s osadníky.[8]

Časný život a roky otroctví

O životě Tisquanta před jeho prvním kontaktem s Evropany není známo téměř nic, a dokonce i kdy a jak k tomuto prvnímu setkání došlo, je předmětem protichůdných tvrzení.[9] Popisy z první ruky psané v letech 1618 až 1622 nezmiňují jeho mládí ani stáří a Salisbury navrhl, že mu bylo dvacet nebo třicet, když se v roce 1614 vydal do Španělska.[10] Pokud by tomu tak bylo, narodil by se kolem roku 1585 (± 10 let).

Tisquantova rodná kultura

Kmeny, které na začátku 17. století žily v jižní Nové Anglii, se o sobě zmiňovaly jako Ninnimissinuok, variace Narragansett slovo Ninnimissinnȗwock což znamená „lidé“ a znamená „známost a sdílená identita“.[11] Tisquantův kmen Patuxety obsadila pobřežní oblast západně od Zátoka Cape Cod, a řekl anglickému obchodníkovi, že patuxetů bylo kdysi 2 000.[12] Mluvili dialektem Východní Algonquian společné kmenům až na západ Zátoka Narragansett.[C] Různé algonquiánské dialekty jižní Nové Anglie byly dostatečně podobné, aby umožňovaly efektivní komunikaci.[d] Termín patuxet odkazuje na web Plymouth, Massachusetts a znamená „při malých pádech“.[E] odkazující na Morisona.[17] Morison dává Mourtův vztah jako autorita pro obě tvrzení.

Roční vegetační období v jižním Maine a Kanadě nebylo dostatečně dlouhé na to, aby se dalo vyprodukovat kukuřice sklizně a indiánské kmeny v těchto oblastech musely žít docela kočovnou existenci,[18] zatímco Algonquins v jižní Nové Anglii byli naopak „sedavými kultivátory“.[19] Rostly dost pro vlastní zimní potřeby a pro obchod, zejména pro severní kmeny, a dost na to, aby ulevily kolonistům v úzkosti po mnoho let, kdy jejich úroda byla nedostatečná.[20]

Skupinám, které tvořily Ninnimissinuok, předsedal jeden nebo dva sachemy.[21] Hlavní funkcí sachemů bylo přidělování půdy pro pěstování,[22] řídit obchod s jinými sachemy nebo vzdálenějšími kmeny,[23] vykonat spravedlnost (včetně trestu smrti),[24] sbírat a ukládat hold z úrody a lovu,[25] a vede ve válce.[26]

Sachemsovi radili „hlavní muži“ volané komunity ahtaskoaog, kolonisty obecně nazývané „šlechtici“. Sachems dosáhl konsensu souhlasem těchto mužů, kteří se pravděpodobně také podíleli na výběru nových sachemů. Když sachemy postoupili zemi, byl obvykle přítomen jeden nebo více hlavních mužů.[27] Byla třída, která se jmenovala pniesesock mezi Pokanokety, kteří sbírali každoroční poctu Sachemu, vedli válečníky do bitvy a měli zvláštní vztah se svým bohem Abbomochem (Hobbomockem), který byl vyvolán v pow wows pro léčivé síly, sílu, kterou kolonisté srovnávali s ďáblem.[F] Třída kněží pocházela z tohoto řádu a šamani také působili jako řečníci a dávali jim politickou moc v rámci svých společností.[32] Salisbury navrhl, že Tisquantum byl pniesesock.[8] Tato třída mohla vyprodukovat něco jako pretoriánskou stráž, což odpovídá „udatným mužům“, které popsal Roger Williams mezi Narragansetts, jedinou společností jižní Nové Anglie s elitní třídou válečníků.[33] Kromě třídy občanů (sanops), byli tu cizinci, kteří se připoutali ke kmeni. Měli málo práv kromě očekávání ochrany před jakýmkoli společným nepřítelem.[32]

Kontakt s Evropany

Ninnimissinuok měl sporadické kontakty s evropskými průzkumníky téměř sto let před přistáním Mayflower v roce 1620. Rybáři z newfoundlandských břehů z Bristol, Normandie, a Bretaň začal provádět každoroční jarní návštěvy počínaje rokem 1581, aby přinesl tresku do jižní Evropy.[34] Tato časná setkání měla dlouhodobé účinky. Evropané mohli zavést nemoci[G] pro které indická populace neměla žádný odpor. Když Mayflower Poutníci zjistili, že celá vesnice postrádá obyvatele.[36] Evropští lovci kožešin obchodovali s různými kmeny, což podporovalo vzájemné soupeření a nepřátelství.[37]

První únosy

V roce 1605 se George Weymouth vydal na expedici, kterou prozkoumal možnost osídlení v horní Nové Anglii Henry Wriothesley a Thomas Arundell.[38] Měli náhodné setkání s loveckou párty, poté se rozhodli unést několik Indů. Zajetí Indů bylo „otázkou velkého významu pro úplné doplnění naší cesty“.[39]

Vzali pět zajatců do Anglie a tři dali sirovi Ferdinando Gorges. Gorges byl investorem do Weymouth plavby a stal se hlavním propagátorem režimu, když Arundell odstoupil od projektu.[40] Gorges psal o jeho radosti z Weymouthova únosu a jmenoval Tisquantum jako jeden ze tří, které mu byly dány.

Kapitán George Weymouth, když se mu nepodařilo najít Severozápadní průchod se stalo v řece na pobřeží Amerika, volala Pemmaquid, odkud přinesl pět domorodců, z nichž tři se jmenovali Manida, Sellwarroes, a Tasquantumkoho jsem se zmocnil, byli všichni z jednoho národa, ale ze všech částí a z různých rodin; Tuto nehodu je třeba uznat, že Bůh má na mysli to, že se postavil na nohy a oživil všechny naše plantáže.[41]

Nepřímé důkazy téměř znemožňují tvrzení, že to bylo Tisquantum mezi těmi, které si vzal Gorges,[h] Adams tvrdí, že „je nepravděpodobné, že by člen kmene Pokánoket absolvoval léto 1605 na návštěvě mezi svými smrtícími nepřáteli Tarratiny, jejichž jazyk pro něj nebyl ani srozumitelný… a byl by zajat jako jeden ze skupiny je způsobem popsaným Rosierem “.[42] a žádný moderní historik to nebaví jako fakt.[i]

Únos Tisquanta

V roce 1614 vedla anglická expedice John Smith plul podél pobřeží Maine a Massachusetts Bay a sbíral ryby a kožešiny. Smith se vrátil do Anglie na jednom z plavidel a nechal Thomase Hunta ve vedení druhé lodi. Hunt měl dokončit hromadu tresky a pokračovat k Malaga Ve Španělsku, kde byl trh se sušenými rybami,[43] ale Hunt se rozhodl zvýšit hodnotu své zásilky přidáním lidského nákladu. Odplul na první pohled do přístavu v Plymouthu, aby obchodoval s vesnicí Patuxet, kde pod příslibem obchodu nalákal 20 indiánů na palubu své lodi, včetně Tisquantum.[43] Jakmile byli na palubě, byli uvězněni a loď se plavila přes zátoku Cape Cod, kde Hunt unesl dalších sedm z Nausetů.[44] Poté vyplul do Málagy.

Smith i Gorges nesouhlasili s Huntovým rozhodnutím zotročit indiány.[45] Soutěsky se obávaly vyhlídky na „začátek nové války mezi obyvateli těchto částí a námi“,[46] i když se zdálo, že ho nejvíce znepokojuje, zda tato událost narušila jeho plány na hledání zlata s Epenowem na vinici Marthy.[47] Smith navrhl, aby Hunt dostal své spravedlivé dezerty, protože „tento divoký akt ho držel až do konce před jakýmkoli dalším znehodnocením těchto částí.“[43]

Podle Gorges vzal Hunt Indy k Gibraltarský průliv kde prodal co nejvíce. Ale „Friers (sic) z těchto částí „zjistili, co dělá, a vzali zbývající indiány, aby byli instruováni“ v křesťanské víře; a tak zklamaný tento nehodný kolega ze svých nadějí na zisk “.[48] Žádné záznamy neukazují, jak dlouho žil Tisquantum ve Španělsku, co tam dělal, ani jak se „dostal pryč do Anglie“, jak říká Bradford.[49] Prowse tvrdí, že strávil čtyři roky v otroctví ve Španělsku a poté byl propašován na palubu lodi patřící do Guyovy kolonie, převezen do Španělska a poté do Newfoundlandu.[50] Smith doložil, že Tisquantum žil v Anglii „dobře“, i když neříká, co tam dělal.[51] Guvernér Plymouthu William Bradford ho znal nejlépe a zaznamenal, že v něm žije Cornhill, Londýn s „Mistře Johne Slanie ".[52] Slany byl obchodník a stavitel lodí, který se stal dalším z obchodních dobrodruhů v Londýně v naději, že si vydělá peníze z kolonizujících projektů v Americe, a byl investorem v Východoindická společnost.

Tisquantův návrat do Nové Anglie

Podle zprávy Rada v Plymouthu pro novou Anglii v roce 1622 bylo Tisquantum v Newfoundlandu "s kapitánem." Zedník Guvernér tam za závazek této plantáže “.[53] Thomas Dermer byl u Cuper's Cove v Početí Bay,[54] dobrodruh, který doprovázel Smitha na jeho neúspěšné cestě do Nové Anglie v roce 1615. Tisquantum a Dermer hovořili o Nové Anglii, když byli v Newfoundlandu, a Tisquantum ho přesvědčil, že by tam mohl zbohatnout, a Dermer napsal Gorges a požádal, aby mu Gorges poslal provizi za jednání v Nové Anglii.

Ke konci roku 1619 se Dermer a Tisquantum plavili po pobřeží Nové Anglie do zátoky Massachusetts. Zjistili, že všichni obyvatelé zemřeli v domovské vesnici Tisquantum v Patucketu, a tak se přestěhovali do vnitrozemí do vesnice Nemask. Dermer poslal Tisquantum[55] do vesnice Pokanoket poblíž Bristol, Rhode Island, sídlo šéfa Massasoita. O několik dní později dorazil Massasoit do Nemasket spolu s Tisquantem a 50 válečníky. Není známo, zda se Tisquantum a Massasoit setkali před těmito událostmi, ale jejich vzájemné vztahy lze vysledovat přinejmenším k tomuto datu.

Dermer se vrátil do Nemasketu v červnu 1620, ale tentokrát zjistil, že tamní Indiáni nesli „zlověstnou zlobu vůči Angličanům“, podle dopisu z 30. června 1620 přepsaného Bradfordem. Tato náhlá a dramatická změna od přátelství k nepřátelství byla způsobena incidentem z předchozího roku, kdy evropské pobřežní plavidlo lákalo některé indiány na palubu s příslibem obchodu, jen aby je nemilosrdně zabili. Dermer napsal, že „Squanto nemůže popřít, ale zabili by mě, když jsem byl v Nemasku, kdyby pro mě tvrdě neprosil.“[56]

Nějaký čas po tomto setkání zaútočili Indiáni na Dermera a Tisquanta a jejich stranu na vinici Marthy a Dermer dostal „14 smrtelných ran v tomto procesu“.[57] Utekl do Virginie, kde zemřel, ale o Tisquantově životě není nic známo, dokud se najednou neobjeví poutníkům v Plymouthské kolonii.

Plymouthská kolonie

Massachusettští indiáni byli na sever od Plymouthské kolonie, vedeni náčelníkem Massasoitem, a kmen Pokanoketů byl na severu, východě a jihu. Tisquantum žil s Pokanokety, protože jeho rodný kmen Patuxetů byl účinně vyhuben před příchodem Mayflower; Poutníci skutečně založili své dřívější bydlení jako místo Plymouthské kolonie.[58] Kmen Narragansett obýval Rhode Island.

Massasoit stál před dilematem, zda uzavřít spojenectví s plymouthskými kolonisty, kteří by ho mohli chránit před Narragansetts, nebo se pokusit sestavit kmenovou koalici, aby kolonisty vyhnal. Rozhodnout o problému, podle Bradfordova účtu, „dostali všechny Powachy země, na tři dny společně děsným a ďábelským způsobem, aby je zaklínali a popravili svými zaklínadly, které shromáždění a službu drželi ve tmě neutěšený bažina. “[59] Philbrick to považuje za shromáždění šamanů, kteří se spojili, aby kolonisty vyhnali z břehů nadpřirozenými prostředky.[j] Tisquantum žil v Anglii a řekl Massassoitovi „jaké divy tam viděl“. Vyzval Massasoita, aby se spřátelil s plymouthskými kolonisty, protože jeho nepřátelé by pak byli „nuceni se mu klanět“.[60] Také spojen s Massasoit byl Samoset, nezletilý Abenakki sachem, který pocházel z Muscongus Bay oblast Maine. Samoset (nesprávná výslovnost Somerseta) se v Anglii naučil angličtinu jako zajatec Merchant Tailors Guild.

V pátek 16. března prováděli osadníci vojenský výcvik, když do osady „odvážně přišel sám“ Samoset.[61] Kolonisté byli zpočátku znepokojeni, ale on okamžitě uvolnil jejich obavy tím, že požádal o pivo.[62] Celý den jim dával informace o okolních kmenech, pak zůstal na noc. Následujícího dne se Samoset vrátil s pěti muži, všichni nesoucí jelení kůže a jednu kočičí kůži. Osadníci je bavili, ale odmítli s nimi obchodovat, protože byla sobota, ačkoli je povzbuzovali, aby se vrátili s dalšími kožešinami. Všichni odešli, ale Samoset, který setrval až do středy a předstíral nemoc.[63] Ve čtvrtek 22. března se vrátil ještě jednou, tentokrát s Tisquantem. Muži přinesli důležité zprávy: Massasoit, jeho bratr Quadrquina a všichni jejich muži byli poblíž. Po hodinové diskusi se na Strawberry Hill objevil sachem a jeho vlak 60 mužů. Kolonisté i Massasoitovi muži nebyli ochotni učinit první krok, ale Tisquantum pendloval mezi skupinami a uskutečnil jednoduchý protokol, který umožňoval Edwardu Winslowovi přiblížit se k sachem. Winslow s Tisquantem jako překladatelem prohlásil láskyplné a pokojné úmysly král James a touha jejich guvernéra obchodovat a uzavřít s ním mír.[64] Poté, co Massasoit jedl, Miles Standish vedl ho k domu, který byl vybaven polštáři a kobercem. Guvernér Carver pak přišel „s Drummem a Trumpetem po něm“ na setkání s Massasoitem. Strany jedly společně, poté vyjednaly smlouvu o míru a vzájemné obraně mezi osadníky z Plymouthu a lidmi z Pokanoketu.[65] Podle Bradforda „po celou dobu, co seděl u Governoura, se třásl strachem“.[66] Massasoitovi následovníci tleskali smlouvě,[66] a mírové podmínky dodržovaly obě strany během Massasoitova života.

Tisquantum jako průvodce hraničním přežitím

Massasoit a jeho muži odešli den po smlouvě, ale Samoset a Tisquantum zůstali.[67] Tisquantum a Bradford si vytvořili blízké přátelství a Bradford se na něj během let, kdy byl guvernérem kolonie, silně spoléhal. Bradford ho považoval za „speciální nástroj poslaný Bohem k jejich dobru nad jejich očekávání“.[68] Tisquantum je naučil dovednosti přežití a seznámil je s jejich prostředím. „Nařídil jim, jak připravit jejich kukuřici, kam vzít ryby, a jak obstarat další komodity, a byl také jejich pilotem, který je za účelem jejich zisku přivedl na neznámá místa, a nikdy je neopustil, dokud nezemřel.“[68]

Den poté, co Massasoit opustil Plymouth, strávil Tisquantum den v Řeka úhoře šlapání úhořů z bahna nohama. Kbelík úhořů, které přinesl zpět, byl „tlustý a sladký“.[69] Sběr úhořů se stal součástí každoroční praxe osadníků. Bradford se však zvláště zmiňuje o pokynech Tisquantum týkajících se místního zahradnictví. Dorazil v době výsadby plodin pro tento rok a Bradford řekl, že „Squanto je postavil na místo něho a ukázal jim jak způsoby, jak je nastavit, tak i poté, jak je oblékat a ošetřovat.“[70] Bradford napsal, že Sqanto jim ukázal, jak hnojit vyčerpanou půdu:

Řekl jim, až na to, že dostali ryby a zasypali je [semeno kukuřice] na těchto starých pozemcích, takže to nevyšlo. A ukázal jim, že v polovině dubna by měli mít na skladě dostatek ryb, aby vyšli k potoku, u kterého začali stavět, a naučil je, jak to vzít a kde získat další opatření, která jsou pro ně nezbytná. To vše zjistili zkouškou a zkušenostmi.[71]

Stejný názor na hodnotu indických pěstitelských metod uvedl Edward Winslow v dopise Anglii na konci roku:

Poslední jaro jsme nastavili na dvacet akrů indický Corne a zasel asi šest akrů Barly a Pease; a podle způsobu Indiáni„Hnojili jsme naši zemi Heringem nebo spíše Shaddem, kterého máme v hojné míře, a s velkou lehkostí se držíme u našich dveří. Naše kukuřice se osvědčila a Bůh se modlí, měli jsme dobrý nárůst indický-Corne a naše Barly lhostejně dobrá, ale náš Pease nestál za shromáždění, protože jsme se obávali, že jsou příliš pozdě.[72]

Metoda, kterou ukázal Tisquantum, se stala běžnou praxí osadníků.[73] Tisquantum také ukázal plymouthským kolonistům, jak mohou získat kožešiny s „několika drobnými komoditami, které si nejprve přinesli“. Bradford uvedl, že mezi nimi nebyl „nikdo, kdo by někdy viděl bobří kůži, dokud sem nepřišli a nebyli informováni Squanto“.[74] Obchodování s kožešinami se stalo pro kolonisty důležitým způsobem, jak splatit svůj finanční dluh svým finančním sponzorům v Anglii.

Role Tisquanta v osadnické diplomacii

Thomas Morton uvedl, že Massasoit byl osvobozen v důsledku mírové smlouvy a „trpěl [Tisquantum] žít s Angličany“,[75] a Tisquantum zůstal věrný kolonistům. Jeden komentátor uvedl, že osamělost způsobená hromadným vyhynutím jeho lidu byla motivem jeho připoutanosti k plymouthským osadníkům.[76] Další navrhl, že to byl vlastní zájem, který si vymyslel, když byl v zajetí Pokanoketu.[77] Osadníci byli nuceni spoléhat na Tisquantum, protože byl jediným prostředkem, kterým mohli komunikovat s okolními indiány, a byl zapojen do každého kontaktu po dobu 20 měsíců, kdy s nimi žil.

Mise do Pokanoketu

Plymouthská kolonie v červnu rozhodla, že mise na Massasoit v Pokatoketu zvýší jejich bezpečnost a sníží počet návštěv Indů, kteří vyčerpali své potravní zdroje. Winslow napsal, že chtějí zajistit, aby mírová smlouva byla Pokanoketem stále ceněna, a prozkoumat okolní zemi a sílu různých kmenů. Rovněž doufali, že projeví ochotu splatit obilí, které vzali na Cape Cod předchozí zimu, slovy Winslowa, „aby se uspokojili s některými počatými zraněními, která mají být způsobena na našich koncích“.[78]

Guvernér Bradford vybral Edwarda Winslowa a Stephen Hopkins udělat cestu s Tisquantem. Vyrazili 2. července[k] nesoucí „Horse-mans kabát“ jako dárek pro Massasoit vyrobený z červené bavlny a zdobený „jemnou krajkou“. Vzali také měděný řetěz a poselství vyjadřující jejich přání pokračovat a posilovat mír mezi oběma národy a vysvětlovat účel řetězu. Kolonie si nebyla jistá svou první sklizní a požádali Massasoita, aby zabránil svým lidem v návštěvě Plymouthu tak často, jak měli - ačkoli si přáli vždy pobavit každého hosta Massasoitu. Kdyby tedy někomu dal řetěz, věděli by, že návštěvníka poslal on, a vždy by ho přijali. Zpráva se také pokusila vysvětlit chování osadníků na Cape Cod, když vzali trochu kukuřice, a požádali, aby poslal své muže do Nausetu, aby vyjádřili přání osadníků provést restituci. Odjeli v 9 hodin ráno,[82] a cestoval dva dny setkáním s přátelskými indiány. Když dorazili do Pokanoketu, bylo třeba poslat Massasoita a Winslow a Hopkins mu při příjezdu pozdravili svými mušketami, na Tisquantův návrh. Massasoit byl vděčný za kabát a ujistil je o všech bodech, které učinili. Ujistil je, že jeho 30 přítokových vesnic zůstane v míru a přinese kožešiny do Plymouthu. Kolonisté zůstali dva dny,[83] poté poslal Tisquantum do různých vesnic, aby hledali obchodní partnery pro Angličany, zatímco oni se vrátili do Plymouthu.

Mise do Nausetu

Winslow píše, že mladý John Billington se zatoulal a pět dní se nevrátil. Bradford poslal zprávu Massasoitovi, který se dotazoval a zjistil, že dítě putovalo do vesnice Manumett, která ho předala Nausetům.[84] Deset osadníků vyrazilo a vzalo Tisquantum jako překladatele a Tokamahamona jako „zvláštního přítele“, podle Winslowových slov. Pluli do Cummaquid do večera a přenocoval v zátoce. Ráno byli dva indiáni na palubě vysláni, aby si promluvili se dvěma indiány, kteří lobovali. Bylo jim řečeno, že chlapec byl v Nausetu, a indiáni z Cape Cod vyzvali všechny muže, aby si s sebou vzali jídlo. Kolonisté z Plymouthu počkali, až příliv dovolí člunu dostat se na břeh, a poté byli eskortováni do Sachemu Iyanough kterému bylo v jeho polovině 20. let a „velmi osobním, jemným, zdvořilým a fayre podmíněným, opravdu ne jako Savage“, podle Winslowových slov. Kolonisté byli bohatě pobaveni a Iyanough dokonce souhlasil, že je bude doprovázet k Nausetům.[85] Zatímco v této vesnici potkali starou ženu „ne méně než sto yeerů starou“, která chtěla vidět kolonisty, a řekla jim o tom, jak Hunt unesl její dva syny ve stejnou dobu jako Tisquantum, a od té doby je neviděla. Winslow ji ujistil, že s indiány se takhle nebudou chovat, a „dal jí nějaké maličkosti, které ji trochu uklidnily“.[86] Po obědě osadníci odvedli loď do Nausetu se sachemem a dvěma členy jeho skupiny, ale příliv zabránil lodi v dosažení břehu, a tak kolonisté poslali Inyanough a Tisquantum, aby se setkali s nausetským sachem Aspinetem. Kolonisté zůstali ve své šalotce a Nausetští muži přišli „velmi tlustí“, aby je přiměli, aby přišli na břeh, ale Winslowova skupina se bála, protože to bylo právě místo Prvního setkání. Jeden z Indů, jehož kukuřici vzali předchozí zimu, jim vyšel vstříc a slíbili mu, že mu to zaplatí.[l] Té noci přijel sachem s více než 100 muži, odhadli kolonisté, a chlapce vynesl na šalotku. Kolonisté dali Aspinetovi nůž a jeden muži, který chlapce odnesl na loď. Tím Winslow usoudil, že „s námi uzavřeli mír“.

Nausetové odešli, ale kolonisté se dozvěděli (pravděpodobně z Tisquanta), že Narragansetti zaútočili na Pokanokety a dobyli Massasoit. To způsobilo velký poplach, protože jejich vlastní osídlení nebylo dobře střeženo, protože jich bylo na této misi tolik. Muži se okamžitě pokusili vyrazit, ale neměli čerstvou vodu. Poté, co se znovu zastavili v Iyanoughově vesnici, vyrazili do Plymouthu.[88] Tato mise vyústila v pracovní vztah mezi osadníky z Plymouthu a indiány z Cape Cod, jak Nausets, tak Cummaquid, a Winslow připsal tento výsledek Tisquantum.[89] Bradford napsal, že Indové, jejichž kukuřici vzali předchozí zimu, přišli a dostali odškodnění a mír obecně převládal.[90]

Akce na záchranu Tisquantum v Nemasketu

Muži se po záchraně Billingtonova chlapce vrátili do Plymouthu a bylo jim potvrzeno, že Massasoit byl vyloučen nebo zajat Narragansetty.[91] To se také naučili Corbitant, Pocasset[92] sachem, dříve přítok Massasoitu, se v Nemasketu pokoušel vypudit tuto kapelu z Massasoitu. Corbitant údajně také brojil proti mírovým iniciativám, které právě měli plymouthští osadníci s Cummaquidem a Nausetem. Tisquantum byl předmětem Corbitantova hněvu kvůli jeho roli při zprostředkování míru s indiány Cape Cod, ale také proto, že byl hlavním prostředkem, kterým mohli osadníci komunikovat s indiány. „Pokud byl mrtvý, Angličané ztratili jazyk,“ řekl údajně.[93] Hobomok byl Pokanoket pniese bydlící u kolonistů,[m] a také mu bylo vyhrožováno za jeho loajalitu k Massasoitovi.[95] Tisquantum a Hobomok byli zjevně příliš vyděšení, aby vyhledali Massasoita, a místo toho šli do Nemasketu, aby zjistili, co mohli. Tokamahamon však šel hledat Massasoita. Corbitant objevil Tisquantum a Hobomok v Nemasket a zajal je. Držel Tisquantum s nožem na prsou, ale Hobomok se uvolnil a běžel do Plymouthu, aby je upozornil, protože si myslel, že Tisquantum zemřel.[96]

Guvernér Bradford zorganizoval ozbrojenou pracovní skupinu asi tuctu mužů pod velením Milese Standisha,[97][98] a vyrazili před svítáním 14. srpna[99] pod vedením Hobomoka. V plánu bylo pochodovat těch 14 mil do Nemasketu, odpočinout si a poté v noci nevědomky odvést vesnici. Překvapení bylo úplné a vesničané byli vyděšení. Kolonisté nemohli přimět Indy pochopit, že hledají pouze Corbitanta, a z domu se pokoušeli uniknout „tři ranění“.[100] Kolonisté si uvědomili, že Tisquantum je nezraněný a pobývá ve vesnici a že Corbitant a jeho muži se vrátili do Pocasetu. Kolonisté prohledali obydlí a Hobomok se dostal na jeho vrchol a volal po Tisquantu a Tisquantovi, kteří oba přišli. Osadníci zabavili dům na noc. Následujícího dne vysvětlili vesnici, že se zajímají pouze o Corbitanta a ty, kteří ho podporují. Varovali, že budou požadovat odplatu, pokud jim Corbitant bude i nadále vyhrožovat, nebo pokud se Massasoit nevrátí z Narragansetts, nebo pokud se někdo pokusí ublížit některému z Massasoitových poddaných, včetně Tisquantum a Hobomok. Poté pochodovali zpět do Plymouthu s vesničany Nemask, kteří pomáhali nést jejich vybavení.[101]

Bradford napsal, že tato akce vyústila v pevnější mír a že „potápěčské sachemy“ osadníkům blahopřáli a další se s nimi vyrovnali. I Corbitant uzavřel mír prostřednictvím Massasoitu.[99] Nathaniel Morton později zaznamenal, že devět sub-sachemů přišlo do Plymouthu 13. září 1621 a podepsali dokument, ve kterém se prohlásili „Loajální poddaní krále JamesKrál Velká Británie, Francie a Irsko".[102]

Mise k lidem v Massachusetu

Kolonisté z Plymouthu se rozhodli setkat s indiány z Massachusetts, kteří je často ohrožovali.[103] 18. srpna vyrazila kolem půlnoci posádka deseti osadníků, tlumočníci Tisquantum a další dva Indové v naději, že dorazí před svítáním. Ale špatně odhadli vzdálenost a byli nuceni zakotvit na břehu a zůstat v shallop přes další noc.[104] Jakmile vystoupili na břeh, našli ženu přicházející sbírat uvězněné humry a ona jim řekla, kde jsou vesničané. Byl vyslán Tisquantum ke kontaktu a zjistili, že sachem předsedá značně omezenému pásmu následovníků. Jmenoval se Obbatinewat a byl přítokem Massasoitu. Vysvětlil, že jeho aktuální poloha v bostonském přístavu nebyla trvalým pobytem, protože se pravidelně pohyboval, aby se vyhnul Tarentinům[n] a Squa Sachim (vdova po Nanepashemet ).[106] Obbatinewat souhlasil, že se poddá králi Jamesovi výměnou za slib kolonistů, že ho ochrání před svými nepřáteli. Rovněž je vzal na prohlídku squa sachem přes Massachusetts Bay.

V pátek 21. září vystoupili kolonisté na břeh a pochodovali domem, kde byl pohřben Nanepashemet.[107] Zůstali tam a poslali Tisquantum a dalšího Inda, aby našli lidi. Objevily se náznaky uspěchaného odstranění, ale našli ženy spolu s obilím a později muže, který byl přiveden k chvění osadníků. Ujistili ho, že nemají v úmyslu ublížit, a on souhlasil, že s nimi bude obchodovat s kožešinami. Tisquantum vyzval kolonisty, aby jednoduše „pušili“ ženy a sundali jejich kůže na zem, že „jsou to špatní lidé a často se vám vyhrožovali,“[108] ale kolonisté trvali na tom, aby s nimi zacházeli spravedlivě. Ženy následovaly muže k šalotce a prodávaly jim všechno, co měli, včetně kabátů z jejich zad. Když kolonisté odpluli, všimli si, že mnoho ostrovů v přístavu bylo obydlených, některé se úplně vyčistily, ale všichni obyvatelé zemřeli.[109] They returned with "a good quantity of beaver", but the men who had seen Boston Harbor expressed their regret that they had not settled there.[99]

The peace regime that Tisquantum helped achieve

During the fall of 1621 the Plymouth settlers had every reason to be contented with their condition, less than one year after the "starving times". Bradford expressed the sentiment with biblical allusion[Ó] that they found "the Lord to be with them in all their ways, and to bless their outgoings and incomings …"[110] Winslow was more prosaic when he reviewed the political situation with respect to surrounding natives in December 1621: "Wee have found the Indiáni very faithfull in their Covenant of Peace with us; very loving and readie to pleasure us …," not only the greatest, Massasoit, "but also all the Princes and peoples round about us" for fifty miles. Even a sachem from Martha's Vineyard, who they never saw, and also seven others came in to submit to King James "so that there is now great peace amongst the Indiáni themselves, which was not formerly, neither would have bin but for us …"[111]

"Díkůvzdání"

Bradford wrote in his journal that come fall together with their harvest of Indian corn, they had abundant fish and fowl, including many turkeys they took in addition to venison. He affirmed that the reports of plenty that many report "to their friends in England" were not "feigned but true reports".[112] He did not, however, describe any harvest festival with their native allies. Winslow, however, did, and the letter which was included in Mourtův vztah became the basis for the tradition of "the first Thanksgiving".[p]

Winslow's description of what was later celebrated as the first Thanksgiving was quite short. He wrote that after the harvest (of Indian corn, their planting of peas were not worth gathering and their barley harvest of barley was "indifferent"), Bradford sent out four men fowling "so we might after a more special manner rejoice together, after we had gathered the fruit of our labours …"[114] The time was one of recreation, including the shooting of arms, and many Natives joined them, including Massasoit and 90 of his men,[q] who stayed three days. They killed five deer which they presented to Bradford, Standish and others in Plymouth. Winslow concluded his description by telling his readers that "we are so farre from want, that we often wish you partakers of our plentie."[116]

The Narragansett threat

The various treaties created a system where the English settlers filled the vacuum created by the epidemic. The villages and tribal networks surrounding Plymouth now saw themselves as tributaries to the English and (as they were assured) King James. The settlers also viewed the treaties as committing the Natives to a form of vassalage. Nathaniel Morton, Bradford's nephew, interpreted the original treaty with Massasoit, for example, as "at the same time" (not within the written treaty terms) acknowledging himeself "content to become the Subject of our Sovereign Lord the King aforesaid, His Heirs and Successors, and gave unto them all the Lands adjacent, to them and their Heirs for ever".[117] The problem with this political and commercial system was that it "incurred the resentment of the Narragansett by depriving them of tributaries just when Dutch traders were expanding their activities in the [Narragansett] bay".[118] In January 1622 the Narraganset responded by issuing an ultimatum to the English.

In December 1621 the Štěstí (which had brought 35 more settlers) had departed for England.[r] Not long afterwards rumors began to reach Plymouth that the Narragansett were making warlike preparations against the English.[s] Winslow believed that that nation had learned that the new settlers brought neither arms nor provisions and thus in fact weakened the English colony.[122] Bradford saw their belligerency as a result of their desire to "lord it over" the peoples who had been weakened by the epidemic (and presumably obtain tribute from them) and the colonists were "a bar in their way".[123] In January 1621/22 a messenger from Narraganset sachem Canonicus (who travelled with Tokamahamon, Winslow's "special friend") arrived looking for Tisquantum, who was away from the settlement. Winslow wrote that the messenger appeared relieved and left a bundle of arrows wrapped in a rattlesnake skin. Rather than let him depart, however, Bradford committed him to the custody of Standish. The captain asked Winslow, who had a "speciall familiaritie" with other Indians, to see if he could get anything out of the messenger. The messenger would not be specific but said that he believed "they were enemies to us." That night Winslow and another (probably Hopkins) took charge of him. After his fear subsided, the messenger told him that the messenger who had come from Canonicus last summer to treat for peace, returned and persuaded the sachem on war. Canonicus was particularly aggrieved by the "meannesse" of the gifts sent him by the English, not only in relation to what he sent to colonists but also in light of his own greatness. On obtaining this information, Bradford ordered the messenger released.[124]

When Tisquantum returned he explained that the meaning of the arrows wrapped in snake skin was enmity; it was a challenge. After consultation, Bradford stuffed the snake skin with powder and shot and had a Native return it to Canonicus with a defiant message. Winslow wrote that the returned emblem so terrified Canonicus that he refused to touch it, and that it passed from hand to hand until, by a circuitous route, it was returned to Plymouth.[125]

Tisquantum's double dealing

Notwithstanding the colonists' bold response to the Narragansett challenge, the settlers realized their defenselessness to attack.[126] Bradford instituted a series of measures to secure Plymouth. Most important they decided to enclose the settlement within a pale (probably much like what was discovered surrounding Nenepashemet's fort). They shut the inhabitants within gates that were locked at night, and a night guard was posted. Standish divided the men into four squadrons and drilled them in where to report in the event of alarm. They also came up with a plan of how to respond to fire alarms so as to have a sufficient armed force to respond to possible Native treachery.[127] The fence around the settlement required the most effort since it required felling suitable large trees, digging holes deep enough to support the large timbers and securing them close enough to each other to prevent penetration by arrows. This work had to be done in the winter and at a time too when the settlers were on half rations because of the new and unexpected settlers.[128] The work took more than a month to complete.[129]

Falešné poplachy

By the beginning of March, the fortification of the settlement had been accomplished. It was now time when the settlers had promised the Massachuset they would come to trade for furs. They received another alarm however, this time from Hobomok, who was still living with them. Hobomok told of his fear that the Massachuset had joined in a confederacy with the Narraganset and if Standish and his men went there, they would be cut off and at the same time the Narraganset would attack the settlement at Plymouth. Hobomok also told them that Tisquantum was part of this conspiracy, that he learned this from other Natives he met in the woods and that the settlers would find this out when Tisquantum would urge the settlers into the Native houses "for their better advantage".[130] This allegation must have come as a shock to the English given that Tisquantum's conduct for nearly a year seemed to have aligned him perfectly with the English interest both in helping to pacify surrounding societies and in obtaining goods that could be used to reduce their debt to the settlers' financial sponsors. Bradford consulted with his advisors, and they concluded that they had to make the mission despite this information. The decision was made partly for strategic reasons. If the colonists cancelled the promised trip out of fear and instead stayed shut up "in our new-enclosed towne", they might encourage even more aggression. But the main reason they had to make the trip was that their "Store was almost emptie" and without the corn they could obtain by trading "we could not long subsist …"[131] The governor therefore deputed Standish and 10 men to make the trip and sent along both Tisquantum and Hobomok, given "the jealousy between them".[132]

Not long after the shallop departed, "an Indian belonging to Squanto's family" came running in. He betrayed signs of great fear, constantly looking behind him as if someone "were at his heels". He was taken to Bradford to whom he told that many of the Narraganset together with Corbitant "and he thought Massasoit" were about to attack Plymouth.[132] Winslow (who was not there but wrote closer to the time of the incident than did Bradford) gave even more graphic details: The Native's face was covered in fresh blood which he explained was a wound he received when he tried speaking up for the settlers. In this account he said that the combined forces were already at Nemasket and were set on taking advantage of the opportunity supplied by Standish's absence.[133] Bradford immediately put the settlement on military readiness and had the ordnance discharge three rounds in the hope that the shallop had not gone too far. Because of calm seas Standish and his men had just reached Gurnet's Nose, heard the alarm and quickly returned. When Hobomok first heard the news he "said flatly that it was false …" Not only was he assured of Massasoit's faithfulness, he knew that his being a pniese meant he would have been consulted by Massasoit before he undertook such a scheme. To make further sure Hobomok volunteered his wife to return to Pokanoket to assess the situation for herself. At the same time Bradford had the watch maintained all that night, but there were no signs of Natives, hostile or otherwise.[134]

Hobomok's wife found the village of Pokanoket quiet with no signs of war preparations. She then informed Massasoit of the commotion at Plymouth. The sachem was "much offended at the carriage of Tisquantum" but was grateful for Bradford's trust in him [Massasoit]. He also sent word back that he would send word to the governor, pursuant to the first article of the treaty they had entered, if any hostile actions were preparing.[135]

Allegations against Tisquantum

Winslow writes that "by degrees wee began to discover Tisquantum," but he does not describe the means or over what period of time this discovery took place. There apparently was no formal proceeding. The conclusion reached, according to Winslow, was that Tisquantum had been using his proximity and apparent influence over the English settlers "to make himselfe great in the eyes of" local Natives for his own benefit. Winslow explains that Tisquantum convinced locals that he had the ability to influence the English toward peace or war and that he frequently extorted Natives by claiming that the settlers were about to kill them in order "that thereby hee might get gifts to himself to work their peace …"[136]

Bradford's account agrees with Winslow's to this point, and he also explains where the information came from: "by the former passages, and other things of like nature",[137] evidently referring to rumors Hobomok said he heard in the woods. Winslow goes much further in his charge, however, claiming that Tisquantum intended to sabotage the peace with Massasoit by false claims of Massasoit aggression "hoping whilest things were hot in the heat of bloud, to provoke us to march into his Country against him, whereby he hoped to kindle such a flame as would not easily be quenched, and hoping if that blocke were once removed, there were no other betweene him and honour" which he preferred over life and peace.[138] Winslow later remembered "one notable (though) wicked practice of this Tisquantum"; namely, that he told the locals that the English possessed the "plague" buried under their storehouse and that they could unleash it at will. What he referred to was their cache of gunpowder.[t]

Massasoit's demand for Tisquantum

Captain Standish and his men eventually did go to the Massachuset and returned with a "good store of Trade". On their return, they saw that Massasoit was there and he was displaying his anger against Tisquantum. Bradford did his best to appease him, and he eventually departed. No long afterward, however, he sent a messenger demanding that Tisquantum is put to death. Bradford responded that although Tisquantum "deserved to die both in respect of him [Massasoit] and us", but said that Tisquantum was too useful to the settlers because otherwise, he had no one to translate. Not long afterward, the same messenger returned, this time with "divers others", demanding Tisquantum. They argued that Tisquantum being a subject of Massasoit, was subject, pursuant to the first article of the Peace Treaty, to the sachem's demand, in effect, rendition. They further argued that if Bradford would not produce pursuant to the Treaty, Massasoit had sent many beavers' skins to induce his consent. Finally, if Bradford still would not release him to them, the messenger had brought Massasoit's own knife by which Bradford himself could cut off Tisquantum's head and hands to be returned with the messenger. Bradford avoided the question of Massasoit's right under the treaty[u] but refused the beaver pelts saying that "It was not the manner of the Angličtina to sell men's lives at a price …" The governor called Tisquantum (who had promised not to flee), who denied the charges and ascribed them to Hobomok's desire for his downfall. He nonetheless offered to abide by Bradford's decision. Bradford was "ready to deliver him into the hands of his Executioners" but at that instance, a boat passed before the town in the harbor. Fearing that it might be the French, Bradford said he had to first identify the ship before dealing with the demand. The messenger and his companions, however, "mad with rage, and impatient at delay" left "in great heat".[141]

Tisquantum's final mission with the settlers

Příjezd Vrabec

The ship the English saw pass before the town was not French, but rather a shallop from the Vrabec, a shipping vessel sponsored by Thomas Weston and one other of the Plymouth settlement's sponsors, which was plying the eastern fishing grounds.[142] This boat brought seven additional settlers but no provisions whatsoever "nor any hope of any".[143] In a letter they brought, Weston explained that the settlers were to set up a salt pan operation on one of the islands in the harbor for the private account of Weston. He asked the Plymouth colony, however, to house and feed these newcomers, provide them with seed stock and (ironically) salt, until he was able to send the salt pan to them.[144] The Plymouth settlers had spent the winter and spring on half rations in order to feed the settlers that had been sent nine months ago without provisions.[145] Now Weston was exhorting them to support new settlers who were not even sent to help the plantation.[146] He also announced that he would be sending another ship that would discharge more passengers before it would sail on to Virginia. He requested that the settlers entertain them in their houses so that they could go out and cut down timber to lade the ship quickly so as not to delay its departure.[147] Bradford found the whole business "but cold comfort to fill their hungry bellies".[148] Bradford was not exaggerating. Winslow described the dire straits. They now were without bread "the want whereof much abated the strength and the flesh of some, and swelled others".[149] Without hooks or seines or netting, they could not collect the bass in the rivers and cove, and without tackle and navigation rope, they could not fish for the abundant cod in the sea. Had it not been for shellfish which they could catch by hand, they would have perished.[150] But there was more, Weston also informed them that the London backers had decided to dissolve the venture. Weston urged the settlers to ratify the decision; only then might the London merchants send them further support, although what motivation they would then have he did not explain.[151] That boat also, evidently,[proti] contained alarming news from the South. John Huddleston, who was unknown to them but captained a fishing ship that had returned from Virginia to the Maine fishing grounds, advised his "good friends at Plymouth" of the massacre in the Jamestown settlements podle Powhatan in which he said 400 had been killed. He warned them: "Happy is he whom other men's harms doth make to beware."[155] This last communication Bradford decided to turn to their advantage. Sending a return for this kindness, they might also seek fish or other provisions from the fishermen. Winslow and a crew were selected to make the voyage to Maine, 150 miles away, to a place they had never been.[158] In Winslow's reckoning, he left at the end of May for Damariscove.[w] Winslow found the fishermen more than sympathetic and they freely gave what they could. Even though this was not as much as Winslow hoped, it was enough to keep them going until the harvest.[163]

When Winslow returned, the threat they felt had to be addressed. The general anxiety aroused by Huddleston's letter was heightened by the increasingly hostile taunts they learned of. Surrounding villagers were "glorying in our weaknesse", and the English heard threats about how "easie it would be ere long to cut us off". Even Massasoit turned cool towards the English, and could not be counted on to tamp down this rising hostility. So they decided to build a fort on burying hill in town. And just as they did when building the palisade, the men had to cut down trees, haul them from the forest and up the hill and construct the fortified building, all with inadequate nutrition and at the neglect of dressing their crops.[164]

Weston's English settlers

They might have thought they reached the end of their problems, but in June 1622 the settlers saw two more vessels arrive, carrying 60 additional mouths to feed. These were the passengers that Weston had written would be unloaded from the vessel going on to Virginia. That vessel also carried more distressing news. Weston informed the governor that he was no longer a part of the company sponsoring the Plymouth settlement. The settlers he sent just now, and requested the Plymouth settlement to house and feed, were for his own enterprise. The "sixty lusty men" would not work for the benefit of Plymouth; in fact he had obtained a patent and as soon as they were ready they would settle an area in Massachusetts Bay. Other letters also were brought. The other venturers in London explained that they had bought out Weston, and everyone was better off without him. Weston, who saw the letter before it was sent, advised the settlers to break off from the remaining merchants, and as a sign of good faith delivered a quantity of bread and cod to them. (Although, as Bradford noted in the margin, he "left not his own men a bite of bread.") The arrivals also brought news that the Štěstí had been taken by French pirates, and therefore all their past effort to export American cargo (valued at £500) would count for nothing. Finally Robert Cushman sent a letter advising that Weston's men "are no men for us; wherefore I prey you entertain them not"; he also advised the Plymouth Separatists not to trade with them or loan them anything except on strict collateral."I fear these people will hardly deal so well with the savages as they should. I pray you therefore signify to Squanto that they are a distinct body from us, and we have nothing to do with them, neither must be blamed for their faults, much less can warrant their fidelity." As much as all this vexed the governor, Bradford took in the men and fed and housed them as he did the others sent to him, even though Weston's men would compete with his colony for pelts and other Native trade.[165] But the words of Cushman would prove prophetic.

Weston's men, "stout knaves" in the words of Thomas Morton,[166] were roustabouts collected for adventure[167] and they scandalized the mostly strictly religious villagers of Plymouth. Worse, they stole the colony's corn, wandering into the fields and snatching the green ears for themselves.[168] When caught, they were "well whipped", but hunger drove them to steal "by night and day". The harvest again proved disappointing, so that it appeared that "famine must still ensue, the next year also" for lack of seed. And they could not even trade for staples because their supply of items the Natives sought had been exhausted.[169] Part of their cares were lessened when their coasters returned from scouting places in Weston's patent and took Weston's men (except for the sick, who remained) to the site they selected for settlement, called Wessagusset (now Weymouth ). But not long after, even there they plagued Plymouth, who heard, from Natives once friendly with them, that Weston's settlers were stealing their corn and committing other abuses.[170] At the end of August a fortuitous event staved off another starving winter: the Objev, bound for London, arrived from a coasting expedition from Virginia. The ship had a cargo of knives, beads and other items prized by Natives, but seeing the desperation of the colonists the captain drove a hard bargain: He required them to buy a large lot, charged them double their price and valued their beaver pelts at 3s. per pound, which he could sell at 20s. "Yet they were glad of the occasion and fain to buy at any price …"[171]

Trading expedition with Weston's men

The Charita returned from Virginia at the end of September–beginning of October. It proceeded on to England, leaving the Wessagusset settlers well provisioned. The Labuť was left for their use as well.[172] It was not long after they learned that the Plymouth settlers had acquired a store of trading goods that they wrote Bradford proposing that they jointly undertake a trading expedition, they to supply the use of the Labuť. They proposed equal division of the proceeds with payment for their share of the goods traded to await arrival of Weston. (Bradford assumed they had burned through their provisions.) Bradford agreed and proposed an expedition southward of the Cape.[173]

Winslow wrote that Tisquantum and Massasoit had "wrought" a peace (although he doesn't explain how this came about). With Tisquantum as guide, they might find the passage among the Monomoy Shoals na Zvuk Nantucket;[X] Tisquantum had advised them he twice sailed through the shoals, once on an English and once on a French vessel.[175] The venture ran into problems from the start. When in Plymouth Richard Green, Weston's brother-in-law and temporary governor of the colony, died. After his burial and receiving directions to proceed from the succeeding governor of Wessagusset, Standish was appointed leader but twice the voyage was turned back by violent winds. On the second attempt, Standish fell ill. On his return Bradford himself took charge of the enterprise.[176] In November they set out. When they reached the shoals, Tisquantum piloted the vessel, but the master of the vessel did not trust the directions and bore up. Tisquantum directed him through a narrow passage, and they were able to harbor near Mamamoycke (now Chatham ).

That night Bradford went ashore with a few others, Tisquantum acting as translator and facilitator. Not having seen any of these Englishmen before, the Natives were initially reluctant. But Tisquantum coaxed them and they provided a plentiful meal of venison and other victuals. They were reluctant to allow the English to see their homes, but when Bradford showed his intention to stay on shore, they invited him to their shelters, having first removed all their belongings. As long as the English stayed, the Natives would disappear "bag and baggage" whenever their possessions were seen. Eventually Tisquantum persuaded them to trade and as a result, the settlers obtained eight hogsheads of corn and beans. The villagers also told them that they had seen vessels "of good burthen" pass through the shoals. And so, with Tisquantum feeling confident, the English were prepared to make another attempt. But suddenly Tisquantum became ill and died.[177]

Tisquantum's death

The sickness seems to have greatly shaken Bradford, for they lingered there for several days before he died. Bradford described his death in some detail:

In this place Tisquantum fell sick of Indian fever, bleeding much at the nose (which the Indians take as a symptom of death) and within a few days died there; desiring the Governor to pray for him, that he might go to the Englishmen's God in Heaven; and bequeathed sundry of his things to English friends, as remembrances of his love; of whom they had a great loss.[178]

Without Tisquantum to pilot them, the English settlers decided against trying the shoals again and returned to Cape Cod Bay.[179]

The English Separatists were comforted by the fact that Tisquantum had become a Christian convert. William Wood writing a little more than a decade later explained why some of the Ninnimissinuok began recognizing the power of "the Englishmens God, as they call him": "because they could never yet have power by their conjurations to damnifie the Angličtina either in body or goods" and since the introduction of the new spirit "the times and seasons being much altered in seven or eight years, freer from lightning and thunder, and long droughts, suddaine and tempestuous dashes of rain, and lamentable cold Winters".[180]

Philbrick speculates that Tisquantum may have been poisoned by Massasoit. His bases for the claim are (i) that other Native Americans had engaged in assassinations during the 17th century; and (ii) that Massasoit's own son, the so-called Král Filip, may have assassinated John Sassamon, an event that led to the bloody Válka krále Filipa a half-century later. He suggests that the "peace" Winslow says was lately made between the two could have been a "rouse" but does not explain how Massasoit could have accomplished the feat on the very remote southeast end of Cape Cod, more than 85 miles distant from Pokanoket.[181]

Tisquantum is reputed to be buried in the village of Chatham Port.[y]

Assessment, memorials, representations, and folklore

Historické hodnocení

Because almost all the historical records of Tisquantum were written by English Separatists and because most of that writing had the purpose to attract new settlers, give account of their actions to their financial sponsors or to justify themselves to co-religionists, they tended to relegate Tisquantum (or any other Native American) to the role of assistant to them in their activities. No real attempt was made to understand Tisquantum or Native culture, particularly religion. The closest that Bradford got in analyzing him was to say "that Tisquantum sought his own ends and played his own game, … to enrich himself". But in the end, he gave "sundry of his things to sundry of his English friends".[178]

Historians' assessment of Tisquantum depended on the extent they were willing to consider the possible biases or motivations of the writers. Earlier writers tended to take the colonists' statements at face value. Current writers, especially those familiar with ethnohistorical research, have given a more nuanced view of Tisquantum, among other Native Americans. As a result, the assessment of historians has run the gamut. Adams characterized him as "a notable illustration of the innate childishness of the Indian character".[183] By contrast, Shuffelton says he "in his own way, was quite as sophisticated as his English friends, and he was one of the most widely traveled men in the New England of his time, having visited Spain, England, and Newfoundland, as well as a large expanse of his own region."[184] Early Plymouth historian Judge John Davis, more than a half century before, also saw Tisquantum as a "child of nature", but was willing to grant him some usefulness to the enterprise: "With some aberrations, his conduct was generally irreproachable, and his useful services to the infant settlement, entitle him to grateful remembrance."[185] In the middle of the 20th century Adolf was much harder on the character of Tisquantum ("his attempt to aggrandize himself by playing the Whites and Indians against each other indicates an unsavory facet of his personality") but gave him more importance (without him "the founding and development of Plymouth would have been much more difficult, if not impossible.").[186] Most have followed the line that Baylies early took of acknowledging the alleged duplicity and also the significant contribution to the settlers' survival: "Although Squanto had discovered some traits of duplicity, yet his loss was justly deemed a public misfortune, as he had rendered the English much service."[187]

Memorials and landmarks

As for monuments and memorials, although many (as Willison put it) "clutter up the Pilgrim towns there is none to Squanto…"[188] The first settlers may have named after him the peninsula called Squantum once in Dorchester,[189] nyní v Quincy, during their first expedition there with Tisquantum as their guide.[190] Thomas Morton refers to a place called "Squanto's Chappell",[191] but this is probably another name for the peninsula.[192]

Literature and popular entertainment

Tisquantum rarely makes appearances in literature or popular entertainment. Of all the 19th century New England poets and story tellers who drew on pre-Revolution America for their characters, only one seems to have mentioned Tisquantum. A zatímco Henry Wadsworth Longfellow himself had five ancestors aboard the Mayflower, "Námluvy Miles Standish " has the captain blustering at the beginning, daring the savages to attack, yet the enemies he addresses could not have been known to him by name until their peaceful intentions had already been made known:

Let them come if they like, be it sagamore, sachem, or pow-wow,

Aspinet, Samoset, Corbitant, Squanto, or Tokamahamon!

Tisquantum is almost equally scarce in popular entertainment, but when he appeared it was typically in implausible fantasies. Very early in what Willison calls the "Pilgrim Apotheosis", marked by the 1793 sermon of Reverend Chandler Robbins, in which he described the Mayflower settlers as "pilgrims",[193] a "Melo Drama" was advertised in Boston titled "The Pilgrims, Or the Landing of the Forefathrs at Plymouth Rock" filled with Indian threats and comic scenes. In Act II Samoset carries off the maiden Juliana and Winslow for a sacrifice, but the next scene presents "A dreadful Combat with Clubs and Shileds, between Samoset and Squanto".[194] Nearly two centuries later Tisquantum appears again as an action figure in the Disney film Squanto: Příběh válečníka (1994) with not much more fidelity to history. Tisquantum (voiced by Frank Welker ) appears in the first episode ("The Mayflower Voyagers", aired October 21, 1988) of the animated mini-series To je Amerika, Charlie Brown. A more historically accurate depiction of Tisquantum (as played by Kalani Queypo ) se objevil v Kanál National Geographic film Svatí a cizinci, napsáno Eric Overmyer and Seth Fisher, which aired the week of Thanksgiving 2015.[195]

Didactic literature and folklore

Where Tisquantum is most encountered is in literature designed to instruct children and young people, provide inspiration, or guide them to a patriotic or religious truth. This came about for two reasons. First, Lincoln's establishment of Thanksgiving as a national holiday enshrined the New England Anglo-Saxon festival, vaguely associated with an American strain of Protestantism, as something of a national origins myth, in the middle of a divisive Civil War when even some Unionists were becoming concerned with rising non-Anglo-Saxon immigration.[196] This coincided, as Ceci noted, with the "noble savage" movement, which was "rooted in romantic reconstructions of Indians (for example, Hiawatha) as uncorrupted natural beings—who were becoming extinct—in contrast to rising industrial and urban mobs". She points to the Indian Head coin first struck in 1859 "to commemorate their passing.'"[197] Even though there was only the briefest mention of "Thanksgiving" in the Plymouth settlers' writings, and despite the fact that he was not mentioned as being present (although, living with the settlers, he likely was), Tisquantum was the focus around both myths could be wrapped. He is, or at least a fictionalized portrayal of him, thus a favorite of a certain politically conservative American Protestant groups.[z]

The story of the selfless "noble savage" who patiently guided and occasionally saved the "Pilgrims" (to whom he was subservient and who attributed their good fortune solely to their faith, all celebrated during a bounteous festival) was thought to be an enchanting figure for children and young adults. Beginning early in the 20th century Tisquantum entered high school textbooks,[aa] children's read-aloud and self-reading books,[ab] more recently learn-to-read and coloring books[ac] and children's religious inspiration books.[inzerát] Over time and particularly depending on the didactic purpose, these books have greatly fictionalized what little historical evidence remains of Tisquantum's life. Their portraits of Tisquantum's life and times spans the gamut of accuracy. Those intending to teach a moral lesson or tell history from a religious viewpoint tend to be the least accurate even when they claim to be telling a true historical story.[ae] Recently there have been attempts to tell the story as accurately as possible, without reducing Tisquantum to a mere servant of the English.[af] There have even been attempts to place the story in the social and historical context of fur trade, epidemics and land disputes.[198] Almost none, however, have dealt with Tisquantum's life after "Thanksgiving" (except occasionally the story of the rescue of John Billington). An exception to all of that is the publication of a "young adult" version of Philbrick's best-selling adult history.[199] Nevertheless, given the sources which can be drawn on, Tisquantum's story inevitably is seen from the European perspective.

Notes, references and sources

Poznámky

- ^ Kinnicutt proposes meanings for the various renderings of his name: Squantam, a contracted form of Musquqntum meaning "He is angry"; Tantum je zkrácená forma Keilhtannittoom, meaning "My great god"; Tanto, z Kehtanito, for "He is the greatest god": and Tisquqntum, pro Atsquqntum, possibly for "He possesses the god of evil."[6]

- ^ Dockstader writes that Tiquantum means "door" or "entrance", although his source is not explained.[7]

- ^ The languages of Southern New England are known today as Západní Abenaki, Massachusett, Loup A and Loup B, Narragansett, Mohegan-Pequot, a Quiripi-Unquachog.[13] Many 17th-century writers state that numerous people in the coastal areas of Southern New England were fluent in two or more of these languages.[14]

- ^ Roger Williams writes in his grammar of the Narragansett language that "their Dialekty doe exceedingly differ" between the French settlements in Canada and the Dutch settlements in New York, "but (within that compass) a man may, by this helpe, converse with tisíce z Domorodci all over the Countrey."[15]

- ^ Adolf,[16]

- ^ Winslow called this supernatural being Hobbamock (the Indians north of the Pokanokets call it Hobbamoqui, he said) and expressly equated him with the devil.[28] William Wood called this same supernatural being Abamacho and said that it presided over the infernal regions where "loose livers" were condemned to dwell after death.[29] Winslow used the term powah to refer to the shaman who conducted the healing ceremony,[30] and Wood described these ceremonies in detail.[31]

- ^ Pro evropský dovoz Paleopathology existují paleopatologické důkazy tyfus, záškrt, chřipka, spalničky, Plané neštovice, Černý kašel, tuberkulóza, žlutá zimnice, spála, kapavka a neštovice.[35]

- ^ The Indians taken by Weymouth were Eastern Abenaki from Maine, whereas Tisquantum was Patuxet, a Southern New England Algonquin. He lived in Plymouth, where the Archanděl neither reached nor planned to.

- ^ Vidět, např., Salisbury 1982, pp. 265–66 n.15; Shuffelton 1976, str. 109; Adolf 1964, str. 247; Adams 1892, str. 24 n. 2; Deane 1885, str. 37; Kinnicutt 1914, str. 109–11

- ^ Vidět Philbrick 2006, str. 95–96

- ^ Mourtův vztah says that they left on June 10, but Prince points out that it was a Sabbath and therefore unlikely to be the day of their departure.[79] Both he and Young[80] follow Bradford, who recorded that they left on July 2.[81]

- ^ "we promised him restitution, & desired him either to come Patuxet for satisfaction, or else we would bring them so much corne againe, he promised to come, wee used him very kindly for the present."[87]

- ^ Bradford describes him as "a proper lusty man, and a man of account for his valour and parts amongst the Indians".[94]

- ^ The Abeneki were known as "Tarrateens" or "Tarrenteens" and lived on the Kennebec and nearby rivers in Maine. "There was great enmity between the Tarrentines and the Alberginians, or the Indians of Massachusetts Bay."[105]

- ^ Bradford quoted Deuteronomium 32:8, which those familiar would understand the unspoken allusion to a "waste howling wilderness." But the chapter also has the assurance that the Lord kept Jacob "as the apple of his eye."

- ^ So Alexander Young put it as early as 1841.[113]

- ^ Humins surmises that the entourage included sachems and other headmen of the confederation's villages."[115]

- ^ According to John Smith's account in New England Trials (1622), the Štěstí arrived at New Plymouth on November 11, 1621 o.s. and departed December 12.[119] Bradford described the 35 that were to remain as "unexpected or looked for" and detailed how they were less prepared than the original settlers had been, bringing no provisions, no material to construct habitation and only the poorest of clothes. It was only when they entered Cape Cod Bay, according to Bradford, that they began to consider what desperation they would be in if the original colonists had perished. The Štěstí also brought a letter from London financier Thomas Weston complaining about holding the Mayflower for so long the previous year and failing to lade her for her return. Bradford's response was surprisingly mild. They also shipped back three hogshead of furs as well as sasssafras, and clapboard for a total freight value of £500.[120]

- ^ Winslow wrote that the Narragansett had sought and obtained a peace agreement with the Plymouth settlers the previous summer,[121] although no mention of it is made in any of the writings of the settlers.

- ^ The story was revealed by Tisquantum himself when some barrels of gunpowder were unearthed under a house. Hobomok asked what they were, and Tisquantum replied that it was the plague that he had told him and others about. Oddly in a tale of the wickedness of Tisquantum for claiming the English had control over the plague is this addendum: Hobomok asked one of the settlers whether it was true, and the settler replied, "no; But the God of the English had it in store, and could send it at is pleasure to the destruction of his and our enemies."[139]

- ^ The first two numbered items of the treaty as it was printed in Mourtův vztah provided: "1. That neither he nor any of his should injure or doe hurt to any of our people. 2. And if any of his did hurt to any of ours, he should send the offender, that we might punish him."[140] As printed the terms do not seem reciprocal, but Massasoit apparently thought they were. Neither Bradford in his answer to the messenger, nor Bradford or Winslow in their history of this event denies that the treaty entitled Massasoit to the return of Tisquantum.

- ^ The events in Bradford's and Winslow's chronologies, or at least the ordering of the narratives, do not agree. Bradford's order is: (1) Provisions spent, no source of food found; (2) end of May brings shallop from Vrabec with Weston letters and seven new settlers; (3) Charita a Labuť dorazí s vkladem „šedesáti chtíčových mužů“; (4) uprostřed dopisu „jejich rovin“ od Huddlestonu přivezeného „touto lodí“ z východu; (5) Winslow a muži se vracejí s nimi; (6) „letos v létě“ staví pevnost.[152] Winslowova sekvence je: (1) Shallop from Vrabec přijde; (2) konec května 1622, sklad potravin utracený; (3) Winslow a jeho muži plují do Damariscove v Maine; (4) po návratu zjistí stav kolonie mnohem oslabený nedostatkem chleba; (5) Nativní posměšky způsobují, že osadníci začali stavět pevnost na úkor výsadby; (6) konec června - začátek července Charita a Labuť přijet.[153] Níže uvedená chronologie následuje Willisonovu kombinaci dvou účtů.[154] Ačkoli Bradfordovo poměrně neopatrné používání zájmenů činí nejasným, který „pilot“ Winslow následoval na loviště v Maine (který nesl Huddletonův dopis) nebo kdo vlastně přinesl Huddletonův dopis,[155] je pravděpodobné, že shallop z Vrabec a ne další loď od samotného Huddlestona, jak před ním byli Willison a Adams[156] uzavřít. Philbrick má Huddlestonův dopis dorazit po Charita a Labuť, a zmiňuje pouze Winslowovu plavbu na loviště, která by se uskutečnila po skončení rybářské sezóny, pokud by k ní došlo po příjezdu těchto dvou plavidel.[157]

- ^ Ostrovy u řeky Damariscove v Maine brzy poskytovaly rybářům etapy od raných dob.[159] Ostrov Damariscove se na mapě Johna Smitha z roku 1614 nazýval Damerillovy ostrovy. Bradford poznamenal, že v roce 1622 „došlo k vylodění mnohem více lodí“.[160] The Vrabec byla umístěna na těchto pozemcích.[161] Morison uvádí, že 300 až 400 plachet z různých zemí, včetně 30 až 40 angličtiny a také z Virginie, přišlo lovit tyto důvody v květnu a odjížděli v létě.[162] Winslowovým úkolem bylo žebrat nebo si půjčit zásoby od těchto rybářů.

- ^ Jednalo se o stejné „nebezpečné hejna a drtiče“, které způsobily Mayflower vrátit se zpět 9. listopadu 1620 o.s.[174]

- ^ Značka na předním trávníku Centra genealogického výzkumu Nickersona na Orleans Road ve městě Chatham uvádí, že Tisquantum je pohřben v čele Ryderovy zátoky. Nickerson tvrdí, že kostra, která kolem roku 1770 vymývala „z kopce mezi Head of the Bay a Cove's Pond“, byla pravděpodobně Squantoova.[182]

- ^ Vidět, například, "The Story of Squanto". Christian Worldview Journal. 26. srpna 2009. Archivováno od originálu 8. prosince 2013.CS1 maint: BOT: stav původní adresy URL neznámý (odkaz); „Squanto: drama díkůvzdání“. Zaměřte se na rodinu Denní vysílání. 1. května 2007.; „Vyprávějte svým dětem příběh Squanta“. Křesťanské titulky. 19. listopadu 2014.; „Historie indiánů díkůvzdání: Proč Squanto už věděl anglicky“. Bill Petro: Vytváření mezer ve strategii a realizaci. 23. listopadu 2016..

- ^ Ilustrace v záhlaví tohoto článku je například jednou ze dvou Tisquantum v Bricker, Garland Armor (1911). Výuka zemědělství na střední škole. New York: Macmillan Co. (Desky po str. 112.)

- ^ Například, Olcott, Frances Jenkins (1922). Dobré příběhy k velkým narozeninám, uspořádané pro vyprávění a čtení nahlas a pro vlastní čtení dětí. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co. Tato kniha byla znovu vydána knihovnou University of Virginia v roce 1995. Tisquantum je v příbězích s názvem „Otec kolonií Nové Anglie“ (William Bradford), s. 125– označován jako „Tisquantum“ a „Velký indián“. 139. Viz také Bradstreet, Howard (1925). Squanto. [Hartford? Conn.]: [Bradstreet?].

- ^ Např.: Beals, Frank L .; Ballard, Lowell C. (1954). Skutečné dobrodružství s osadníky Pilgrim: William Bradford, Miles Standish, Squanto, Roger Williams. San Francisco: H. Wagner Publishing Co. Bulla, Clyde Robert (1954). Squanto, přítel bílých mužů. New York: T.Y. Crowell. Bulla, Clyde Robert (1956). John Billington, přítel Squanta. New York: Crowell. Stevenson, Augusta; Goldstein, Nathan (1962). Squanto, mladý indický lovec. Indianapolis, Indiana: Bobbs-Merrill. Anderson, A.M. (1962). Squanto a poutníci. Chicago: Wheeler. Ziner, Feenie (1965). Temný poutník. Philadelphia: Chilton Books. Graff, Robert; Graff (1965). Squanto: Indický dobrodruh. Champaign, Illinois: Garrard Publishing Co. Grant, Matthew G. (1974). Squanto: Indián, který zachránil poutníky. Chicago: Kreativní vzdělávání. Jassem, Kate (1979). Squanto: Pilgrim Adventure. Mahwah, New Jersey: Troll Associates. Cole, Joan Wade; Newsom, Tom (1979). Squanto. Oklahoma City, Oklahoma: Economy Co. ;Kessel, Joyce K. (1983). Squanto a první den díkuvzdání. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Carolrhoda Bookr. Rothaus, James R. (1988). Squanto: Indián, který zachránil poutníky (1500-1622). Mankato, Minnesota: Kreativní vzdělávání.;Celsi, Teresa Noel (1992). Squanto a první den díkuvzdání. Austin, Texas: Raintree Steck-Vaughn. Dubowski, Cathy East (1997). The Story of Squanto: First Friend to the P. Milwaukee, Wisconsin: vydavatelé Gareth Stevens. ;Bruchac, Joseph (2000). Squanto's Journey: The Story of the First Thanksgiving. n.l .: Silver Whistle. Samoset a Squanto. Peterborough, New Hampshire: Cobblestone Publishing Co. 2001. Whitehurst, Susan (2002). Partnerství v Plymouthu: Poutníci a domorodí Američané. New York: Press PowerKids. Buckley, Susan Washborn (2003). Squanto the Pilgrims 'Friend. New York: Scholastic. Hirschfelder, Arlene B. (2004). Squanto, 1585 - 1622. Mankato, Minnesota: Blue Earth Books. Roop, Peter; Roop, Connie (2005). Děkuji, Squanto!. New York: Scholastic. Banks, Joan (2006). Squanto. Chicago: Wright Group / McGraw Hill. Ghiglieri, Carol; Noll, Cheryl Kirk (2007). Squanto: Přítel poutníků. New York: Scholastic.

- ^ Např., Hobbs, Carolyn; Roland, Pat (1981). Squanto. Milton, Florida: Vytištěno Dětským biblickým klubem. The Legend of Squanto. Carol Stream, Illinois. 2005. Metaxas, Eric (2005). Squanto a první den díkuvzdání. Rowayton, Connecticut: ABDO Publishing Co. Kniha byla retitled Squanto a zázrak díkůvzdání když byl v roce 2014 znovu vydán náboženským vydavatelem Thomasem Nelsonem. Kniha byla proměněna v animované video Rabbit Ears Entertainment v roce 2007.

- ^ Například, Metaxas 2005, chválen autorovým kolegou jako „skutečný příběh“ Chuck Colson, uvádí nesprávně téměř všechny dobře zdokumentované skutečnosti v Tisquantově životě. Začíná to únosem dvanáctiletého Tisquanta, jehož první věta se datuje „rokem našeho Pána 1608“ (spíše než 1614). Když potká „Poutníky“, pozdraví guvernéra Bradforda (spíše než Carvera). Zbytek je fiktivní náboženské podobenství, které končí tím, že Tisquantum (po „Dni díkůvzdání“ a před jakýmkoli obviněním ze zrady) děkuje Bohu za poutníky.

- ^ Bruchac 2000 například dokonce jmenuje Hunt, Smith a Dermer a pokouší se vykreslit Tisquantum z domorodého Američana, spíše než z pohledu „Pilgrim“.

Reference

- ^ Rose, E.M. (2020). „Setkal se Squanto s Pocahontasem a o čem by mohli diskutovat?“. Junto. Citováno 24. září 2020.

- ^ Baxter 1890, str. 1104 č. 146; Kinnicutt 1914, str. 110–12.

- ^ Mladý 1841, str. 202 č. 1.

- ^ Mann 2005.

- ^ Martin 1978, str. 34.

- ^ Kinnicutt 1914, str. 112.

- ^ Dockstader 1977, str. 278.

- ^ A b Salisbury 1981, str. 230.

- ^ Salisbury 1981, s. 228.

- ^ Salisbury 1981, s. 228–29.

- ^ Bragdon 1996, str. i.

- ^ Dopis Emmanuela Althama jeho bratrovi siru Edwardu Althamovi, září 1623, v James 1963, str. 29. Kopii dopisu rovněž reprodukuje online MayflowerHistory.com.

- ^ Goddard 1978, str.passim.

- ^ Bragdon 1996, s. 28–29, 34.

- ^ Williams 1643, s. [ii] - [iii]. Viz také Salisbury 1981, str. 229.

- ^ Adolf 1964, str. 257 č. 1.

- ^ Bradford 1952, str. 82 č. 7.

- ^ Bennett 1955, str. 370–71.

- ^ Bennett 1955, str. 374–75.

- ^ Russell 1980, s. 120–21; Jennings 1976, str. 65–67.

- ^ Jennings 1976, str. 112.

- ^ Winslow 1924, str. 57 přetištěno na Youmg 1841, str. 361

- ^ Bragdon 1996, str. 146.

- ^ Winslow 1624, str. 59–60 přetištěno na Mladý 1841, str. 364–65; Dřevo 1634, str. 90; Williams 1643, str. 136

- ^ Winslow 1624, str. 57–58 přetištěno na Mladý 1841, s. 362–63; Jennings 1976, str. 113

- ^ Williams 1643, s. 178–79; Brigdon 1996, str. 148–50.

- ^ Bragdon 1996, str. 142.

- ^ Winslow 1624, str. 53 přetištěno na Mladý 1841, str. 356.

- ^ Dřevo 1634, str. 105 Další informace o Abbomochovi vidět Bragdon 1996, s. 143, 188–90, 201–02.

- ^ Winslow 1624, str. 54 přetištěno na Mladý 1841, str. 357.

- ^ Dřevo 1634, str. 92–94.

- ^ A b Robbins 1956, str. 61.

- ^ Bragdon 1996, str. 143.

- ^ Martin 1978, str. 41.

- ^ Martin 1978, str. 43.

- ^ Jennings 1976, s. 15–16, 22–24, 26–31; Martin 1978, str. 43–51.

- ^ Jennings 1976, str. 85–88.

- ^ Burrage 1906, str. 355.

- ^ Rosier 1605 přetištěno na Burrage 1906, str. 379.

- ^ Rosier 1065 přetištěno na Burrage 1906, str. 357.

- ^ Soutěsky 1658 přetištěno na Baxter 1890, str. II: 8.

- ^ Adams 1892, str. 24 č. 2 (pokračování)

- ^ A b C Smith 1907, str. II: 4.

- ^ Mourtův vztah 1622, str. 233 dotisk Mladý 1841, str. 186. Viz také Dunn 1993, str. 39 a Salisbury 1981, str. 234.

- ^ Smith 1907, s. II: 4–5.

- ^ Baxter 1890, str. I: 211. Vidět Salisbury 1981, str. 234.

- ^ Baxter 1890, str. I: 209.

- ^ Soutěsky 1622, str. 11 dotisk Baxter 1890, s. I: 209–10.

- ^ OPP: Bradford 1952, str. 81 a Davis 1908, str. 112.

- ^ Prowse 1895, str. 104 č. 2

- ^ Smith 1907, str. II: 62.

- ^ Mourtův vztah 1622, str. 35 dotisk Mladý 1841, str. 191. Bradford jednoduše poznamenává, že „ho bavil obchodník v Londýně“. OPP: Bradford 1952, str. 81 a Davis 1908, str. 112.

- ^ Soutěsky 1622, str. 13 dotisk Baxter 1890, str. I: 212.

- ^ D. eane 1887, str. 134.

- ^ Dunn 1993, str. 40.

- ^ OPP: Bradford 1952, str. 82 dotisk Davis 1908, str. 112–13.

- ^ Gorger 1658, str. 20 dotisk dovnitř Baxter 1890, str. II: 29.

- ^ Russell 1980, str. 22.

- ^ OPP: Bradford 1952, str. 84 a Davis 1908, str. 114.

- ^ Pratt 1858, str. 485

- ^ Mourtův vztah 1622, str. 31–32 přetištěno Dexter 1865, s. 81–83 a Mladý 1841, s. 181–82.

- ^ Mourtův vztah 1622, str. 33 přetištěno Dexter 1865, str. 84 a Mladý 1841, str. 181.

- ^ Mourtův vztah 1622, str. 33–35 přetištěno Dexter 1865, str. 87–89 a Mladý 1841, s. 186–89.

- ^ Mourtův vztah 1622, str. 35–36 přetištěno Dexter 1865, str. 90–92 a Mladý 1841, s. 190–92.

- ^ Mourtův vztah 1622, str. 36–37 přetištěno Dexter 1865, str. 92–94 a Mladý 1841, str. 192–93.

- ^ A b Mourtův vztah 1622, str. 37 dotisk Dexter 1865, str. 94 a Mladý 1841, str. 194.