Sino-francouzská válka - Sino-French War

| Sino-francouzská válka | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Část Tonkinova kampaň | |||||||||

Operace čínsko-francouzské války (1884–1885) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Bojovníci | |||||||||

| Velitelé a vůdci | |||||||||

| Síla | |||||||||

| 15 000 - 20 000 vojáků | 25 000 - 35 000 vojáků (z provincií Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian, Zhejiang a Yunnan ) | ||||||||

| Ztráty a ztráty | |||||||||

| 4 222 zabitých a zraněných 5 223 zemřelo na nemoc[5] | ~ 10 000 zabito neznámý zraněn[6] | ||||||||

The Sino-francouzská válka (tradiční čínština : 中法 戰爭; zjednodušená čínština : 中法 战争; pchin-jin : Zhōngfǎ Zhànzhēng, francouzština: Guerre franco-chinoise, vietnamština: Chiến tranh Pháp-Thanh), také známý jako Tonkinská válka a Tonquin válka,[7] byl omezený konflikt bojovaný od srpna 1884 do dubna 1885. Nebylo vyhlášení války. Vojensky to byla patová situace. Čínské armády si vedly lépe než v jiných válkách devatenáctého století a válka skončila francouzským ústupem na souši.[1] Jedním z důsledků však bylo, že Francie nahradila čínskou kontrolu nad Tonkin (severní Vietnam ). Válka posílila dominanci Vdova císařovny Cixi nad čínskou vládou, ale svrhl vládu předsedy vlády Jules Ferry v Paříži. Obě strany byly s Smlouva Tientsin.[8] Podle Lloyda Eastmana „ani jeden národ nezískal diplomatické zisky“.[9]

Předehra

Francouzský zájem o severní Vietnam datován od konce 18. století, kdy byl politickým katolickým knězem Pigneau de Behaine přijal francouzské dobrovolníky, aby bojovali Nguyễn Ánh a pomoci začít Dynastie Nguyễn, ve snaze získat privilegia pro Francii a pro Římskokatolický kostel. Francie zahájila svou koloniální kampaň v roce 1858, v roce 1862 anektovala několik jižních provincií a vytvořila kolonii Cochinchina.

Francouzští průzkumníci sledovali průběh červená řeka přes severní Vietnam k jeho zdroji v Yunnan vzbuzuje naděje na ziskovou obchodní cestu s Čínou, která by mohla obejít smluvní přístavy čínských pobřežních provincií.[10] Hlavní překážkou této myšlenky je Armáda černé vlajky - dobře organizovaná banditská síla vedená impozantním Liu Yongfu - vybíral přemrštěné „daně“ z obchodu mezi Red River a S Tn Tây a Lào Cai na hranici Yunnan.

V roce 1873 malá francouzská síla pod velením poručíka de Vaisseau Francis Garnier, přesáhl jeho pokyny, vojensky zasáhl v severním Vietnamu. Po sérii francouzských vítězství proti Vietnamcům vyzvala vietnamská vláda Černé vlajky Liu Yongfu, kteří porazili Garnierovu sílu pod hradbami Hanoi. Garnier byl v této bitvě zabit a francouzská vláda se od jeho expedice později distancovala.[11]

Expedice Henriho Rivièra v Tonkinu

V roce 1881 francouzský velitel Henri Rivière byl vyslán s malou vojenskou silou do Hanoje, aby prošetřil vietnamské stížnosti na činnost francouzských obchodníků.[12] Navzdory pokynům svých nadřízených zaútočil Rivière dne 25. dubna 1882 na hanojskou pevnost.[13] Ačkoli Rivière následně vrátil citadelu vietnamské kontrole, jeho použití síly vyvolalo poplach jak ve Vietnamu, tak v Číně.[14]

Vietnamská vláda, která nebyla schopna konfrontovat Rivière se svou vlastní zchátralou armádou, znovu požádala o pomoc Liu Yongfu, jehož dobře vycvičení a ostřílení vojáci černé vlajky by byli Francouzi trnem v oku. Vietnamci také usilovali o čínskou podporu. Vietnam byl dlouho vazalským státem v Číně a Čína souhlasila, že vyzbrojí a podpoří Černé vlajky a skrytě se postaví proti francouzským operacím v Tonkinu.

Soud Qing také vyslal Francouzům silný signál, že Čína nedovolí, aby Tonkin spadl pod francouzskou kontrolu. V létě roku 1882 vojska Číňanů Yunnanská armáda a Guangxi armáda překročil hranici do Tonkinu a obsadil Lạng Sơn, Bắc Ninh, Hung Hoa a další města.[15] Francouzský ministr v Číně Frédéric Bourée byl tak znepokojen vyhlídkou na válku s Čínou, že v listopadu a prosinci vyjednal dohodu s čínským státníkem Li Hongzhang rozdělit Tonkin na francouzskou a čínskou sféru vlivu. Žádná ze stran těchto jednání nekonzultovala s Vietnamci.[16]

Rivière, znechucený dohodou uzavřenou Bourée, se rozhodl počátkem roku 1883 tento problém vynutit. Nedávno mu byl poslán prapor námořní pěchoty z Francie, který mu dal tolik mužů, aby se mohl vydat za Hanoj. Dne 27. března 1883, aby Rivière zajistil svou komunikační linku z Hanoje k pobřeží, dobyl citadelu Nam Định se silou 520 francouzských vojáků pod jeho osobním velením.[17] Během jeho nepřítomnosti v Nam Định Black Flags a Vietnamese zaútočili na Hanoj, ale šéfkuchař de Bataillon Berthe de Villers je odrazil v Bitva o Gia Cuc dne 28. března.[18] Rivière radostně zareagoval: „To je donutí, aby se dopustili své Tonkinovy otázky!“[Tento citát vyžaduje citaci ]

Rivière měl perfektní načasování. Čekal, že bude za své peníze vyplacen Zachycení Nam Định; místo toho se stal hrdinou hodiny. Nedávno došlo ke změně vlády ve Francii a nové správě Francie Jules Ferry silně upřednostňovaná koloniální expanze. Rozhodlo se proto podpořit Rivière. Ministr trajektů a zahraničí Paul-Armand Challemel-Lacour odsoudil dohodu Bourée s Li Hongzhangem a odvolal nešťastného francouzského ministra.[19] Také Číňanům dali jasně najevo, že jsou odhodláni umístit Tonkina pod francouzskou ochranu. V dubnu 1883 si čínský občan Mandarin Tang Jingsong, který si uvědomil, že Vietnamcům chybí prostředky, jak účinně odolávat Francouzům,Tang Jingsong, 唐景崧) přesvědčil Liu Yongfu, aby s armádou černé vlajky vyrazil na pole proti Rivière. Výsledkem byl rok, kdy síly Liou Yongfu bojovaly s nekonvenční válkou.[20]

Dne 10. května 1883 vyzval Liu Yongfu Francouze k bitvě v posměšném poselství, které bylo na stěnách Hanoje často umístěno. Dne 19. Května Rivière čelila Černým vlajkám v Battle of Paper Bridge a Francouzi utrpěli katastrofální porážku. Rivièrovy malé síly (kolem 450 mužů) zaútočily na silnou obrannou pozici Černé vlajky poblíž vesnice Cầu Giấy, několik kilometrů západně od Hanoje, Francouzům známou jako Paperský most (Pont de Papier). Po počátečních úspěších byli Francouzi nakonec zahaleni na obou křídlech; jen s obtížemi se mohli přeskupit a spadnout zpět do Hanoje. Rivière, Berthe de Villers a několik dalších vyšších důstojníků byli při této akci zabiti.[21]

Francouzský zásah do Tonkina

Riviérova smrt vyvolala ve Francii rozzlobenou reakci. Posily byly poslány do Tonkinu, byl odvrácen hrozící útok Černých vlajek na Hanoj a vojenská situace byla stabilizována.

Protektorát nad Tonkinem

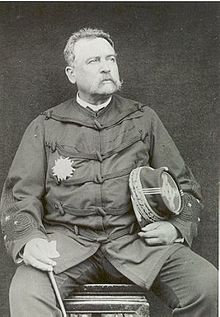

Dne 20. srpna 1883 admirál Amédée Courbet, který byl nedávno jmenován velitelem nově vytvořené námořní divize Tonkin Coasts, zaútočil na pevnosti, které střežily přístupy k vietnamskému hlavnímu městu Huế v Battle of Thuận An, a přinutil vietnamskou vládu podepsat Smlouva o Huế, umístění Tonkin pod francouzskou ochranou.[22]

Současně nový velitel expedičního sboru Tonkin, generál Bouët, zaútočil na pozice Černé vlajky na řece Day. Přestože Francouzi zřídili armádu černých vlajek v Bitva u Phủ Hoài (15. Srpna) a Bitva o Palan (1. září) nebyli schopni obsadit všechny pozice Liu Yongfu a bitvy se v očích světa rovnaly francouzským porážkám. Bouët byl široce považován za neúspěšný ve své misi, a rezignoval v září 1883. V případě, silné povodně nakonec přinutily Liu Yongfu opustit linii řeky Day a spadnout zpět do opevněného města S Tn Tây, několik mil na západ.

Konfrontace mezi Francií a Čínou

Na konci roku se Francouzi připravili na velkou ofenzívu, aby vyhladili Černé vlajky, a pokusili se přesvědčit Čínu, aby zrušila podporu Liu Yongfu, a pokusila se získat podporu dalších evropských mocností pro plánovanou ofenzívu. Avšak jednání v Šanghaji v červenci 1883 mezi francouzským ministrem Arthurem Tricou a Li Hongzhang byly ukončeny vládou Qing po obdržení naivně optimistického hodnocení markýzem Zeng Jize, čínský ministr do Paříže, že francouzská vláda neměla žaludek pro totální válku s Čínou.[23] Jules Ferry a francouzský ministr zahraničí Paul-Armand Challemel-Lacour se setkal několikrát v létě a na podzim roku 1883 s markýzem Zengem v Paříži, ale tyto paralelní diplomatické diskuse se rovněž ukázaly jako neúspěšné.[24] Číňané byli pevní a odmítli stáhnout značné posádky čínských pravidelných vojsk ze Sơn Tây, Bắc Ninh a Lạng Sơn, a to navzdory pravděpodobnosti, že budou brzy zapojeni do boje proti Francouzům. Jelikož se zdálo, že válka s Čínou je stále pravděpodobnější, přesvědčili Francouzi německou vládu, aby odložila propuštění Dingyuan a Zhenyuan, poté byly v německých loděnicích pro čínské postaveny dvě moderní bitevní lodě Beiyang Fleet.[25] Mezitím Francouzi upevnili svoji moc nad Delta vytvořením míst na Quảng Yên, Hưng Yên a Ninh Bình.[26]

Rostoucí napětí mezi Francií a Čínou vyvolalo v Číně během podzimu 1883 proticizinecké demonstrace. K nejzávažnějším událostem došlo v provincii Kuang-tung, kde byli Evropané nejvýznamnější. Byly provedeny útoky na majetek evropských obchodníků v Kantonu a na ostrově Shamian. Několik evropských mocností, včetně Francie, poslalo do Guangzhou dělové čluny, aby chránily své státní příslušníky.

Son Tay a Bac Ninh

Francouzi připustili, že útok na Liu Yongfu pravděpodobně vyústí v nehlášenou válku s Čínou, ale vypočítali, že rychlé vítězství v Tonkinu by Číňany donutilo přijmout fait accompli. Velením Tonkinovy kampaně byl pověřen admirál Courbet, který zaútočil S Tn Tây v prosinci 1883. The Kampaň Sơn Tây byla nejdivočejší kampaň, kterou Francouzi v Tonkinu dosud bojovali. Přestože čínský a vietnamský kontingent v Son Tay hrály při obraně malou roli, Černé vlajky Liu Yongfu divoce bojovaly o udržení města. Dne 14. prosince zaútočili Francouzi na vnější obranu Sơn Tây v Phu Sa, ale byli vrženi zpět s těžkými ztrátami. V naději, že využije Courbetovu porážku, zaútočil Liu Yongfu ve stejnou noc na francouzské linie, ale útok Black Flag také katastrofálně selhal. Po odpočinku svých vojsk dne 15. prosince, Courbet znovu zaútočil na obranu Sơn Tây odpoledne 16. prosince. Tentokrát byl útok důkladně připraven dělostřelectvem a doručen až poté, co byli obránci vyčerpáni. V 17 hodin prapor cizinecké legie a prapor námořních střelců dobyli západní bránu Sơn Tây a probojovali se do města. Posádka Liu Yongfu se stáhla do citadely a o několik hodin později pod rouškou tmy evakuovala Sơn Tây. Courbet dosáhl svého cíle, ale za značné náklady. Francouzské oběti v Son Tay byly 83 mrtvých a 320 zraněných. Boje u Sơn Tây si také vyžádaly strašlivou daň Černých vlajek a podle názoru některých pozorovatelů je jednou provždy zlomily jako vážnou bojovou sílu. Liu Yongfu cítil, že byl úmyslně ponechán nést hlavní tíhu svých čínských a vietnamských spojenců, a rozhodl se, že už nikdy nebude své jednotky tak otevřeně vystavovat.[27]

V březnu 1884 obnovili Francouzi svou ofenzívu pod velením generála Charles-Théodore Millot, který převzal odpovědnost za pozemní kampaň od admirála Courbeta po pádu Sơn Tây. Posily z Francie a afrických kolonií nyní zvýšily sílu Tonkin Expeditionary Corps na více než 10 000 mužů a Millot tuto sílu uspořádal do dvou brigád. 1. brigádě velel generál Louis Brière de l'Isle, který se dříve proslavil jako guvernér Senegalu, a 2. brigádě velel charismatický mladý generál cizinecké legie François de Négrier, který nedávno potlačil vážnou arabskou vzpouru v Alžírsku. Francouzský cíl byl Bắc Ninh, obsazený silnou silou pravidelných čínských jednotek armády Kuang-si.[28] The Bắc Ninh kampaň byla výhra pro Francouze. Morálka v čínské armádě byla nízká a Liu Yongfu dával pozor, aby své zkušené Černé vlajky neohrožoval. Millot obešel čínskou obranu na jihozápad od Bắc Ninh a na město zaútočil 12. března z jihovýchodu s úplným úspěchem. Guangxi armáda kladla slabý odpor a Francouzi se města zmocnili s lehkostí a zajali velké množství munice a řadu zbrusu nových Krupp dělo.[29]

Dohoda Tientsin a Smlouva o Huế

Porážka v Bắc Ninh, blížící se pádu Sơn Tây, posílila ruku umírněného prvku v čínské vládě a dočasně zdiskreditovala extremistickou „puristickou“ stranu vedenou Zhang Zhidong, která agitovala za totální válku proti Francii. Další francouzské úspěchy na jaře 1884, včetně Zachycení Hưng Hóa a Thái Nguyên, přesvědčil Vdova císařovny Cixi že Čína by se měla smířit a v květnu bylo dosaženo dohody mezi Francií a Čínou. Jednání se konala v Tianjinu (Tientin). Li Hongzhang, vůdce čínských umírněných, zastupoval Čínu; a kapitáne François-Ernest Fournier, velitel francouzského křižníku Volta, zastoupená ve Francii. The Tientsin Accord, uzavřená dne 11. května 1884, stanovila čínské uznání francouzského protektorátu nad Annamem a Tonkinem a stažení čínských vojsk z Tonkinu výměnou za komplexní smlouvu, která by urovnala podrobnosti obchodu a obchodu mezi Francií a Čínou a stanovila vymezení jeho sporné hranice s Vietnamem.[30]

Dne 6. června Francouzi navázali na svou dohodu s Čínou uzavřením nového Smlouva o Huế s Vietnamci, kteří založili francouzský protektorát nad Annamem i Tonkinem a umožnili Francouzům rozmístit jednotky na strategických místech vietnamského území a instalovat obyvatele hlavních měst. Podpis smlouvy doprovázelo důležité symbolické gesto. Pečeť předložená čínským císařem o několik desítek let dříve vietnamskému králi Gia Long byla roztavena za přítomnosti francouzských a vietnamských zplnomocněných zástupců, což svědčí o tom, že se Vietnam zřekl svých tradičních vztahů s Čínou.[31]

Fournier nebyl profesionálním diplomatem a dohoda Tientsin obsahovala několik volných konců. Rozhodující je, že výslovně nestanovila lhůtu pro stažení čínských vojsk z Tonkinu. Francouzi tvrdili, že ke stažení vojsk mělo dojít okamžitě, zatímco Číňané tvrdili, že stažení bylo podmíněno uzavřením komplexní smlouvy. Ve skutečnosti byl čínský postoj ex post facto racionalizací, která měla ospravedlnit jejich neochotu nebo neschopnost provést podmínky dohody. Dohoda byla v Číně extrémně nepopulární a vyvolala okamžitou reakci. Válečná strana požadovala obžalobu Li Hongzhanga a jeho politické oponenty zaujalo, aby byly čínským jednotkám v Tonkinu zaslány rozkazy, aby si udrželi své pozice.

Záloha Bắc Lệ

Li Hongzhang naznačil Francouzům, že při prosazování dohody mohou nastat potíže, ale nic konkrétního nebylo řečeno. Francouzi předpokládali, že čínská vojska opustí Tonkin podle dohody, a připravili se na obsazení pohraničních měst Long Son, Cao Bằng a Ten Ke. Na začátku června 1884 francouzská kolona pod velením podplukovníka Alphonse Dugenne postupovala k obsazení Langsona. Dne 23. Června, poblíž městečka Bắc Lệ, Francouzi narazili na silné oddělení armády Guangxi usazené v obranné pozici za řekou Song Thuong. S ohledem na diplomatický význam tohoto objevu měl Dugenne hlásit přítomnost čínských sil Hanoji a čekat na další pokyny. Místo toho dal Číňanům ultimátum a po jejich odmítnutí ustoupit pokračoval v jeho postupu. Číňané zahájili palbu na postupující Francouze, což vyvolalo dvoudenní bitvu, ve které byla Dugennova kolona obklíčena a vážně zřízena. Dugenne se nakonec probojoval z čínského obklíčení a svou malou sílu vyprostil.[32]

Když zprávy oBắc Lệ přepadení „dosáhl Paříže, zuřilo to, co bylo vnímáno jako do očí bijící čínská zrada. Ferryho vláda požadovala omluvu, odškodnění a okamžité provedení podmínek dohody Tianjin. Čínská vláda souhlasila s vyjednáváním, ale odmítla se omluvit nebo vyplatit jakékoli odškodnění. Nálada ve Francii byla proti kompromisu, a přestože jednání pokračovala po celý červenec, admirál Courbet dostal rozkaz odvézt svou letku do Fu-čou (Foochow). Byl pověřen přípravou na útok na Čínská flotila Fujian v přístavu a zničit Foochow Navy Yard. Mezitím jako předběžná ukázka toho, co by následovalo, kdyby se Číňané vzpurili, kontradmirál Sébastien Lespès zničil tři čínské pobřežní baterie v přístavu Keelung v severní Formosě (Tchaj-wan ) námořním bombardováním dne 5. srpna. Francouzi postavili jako „zástavu“ výsadkovou sílu na břeh, aby obsadili Keelung a nedaleké uhelné doly v Pei-tao (Pa-tou) (měřidlo) je třeba vyjednávat proti čínskému stažení z Tonkinu, ale příchod velké čínské armády pod velením císařského komisaře Liu Mingchuan ji 6. srpna donutila znovu nastoupit.[33]

Sino-francouzská válka, srpen 1884 až duben 1885

Provoz letky admirála Courbeta

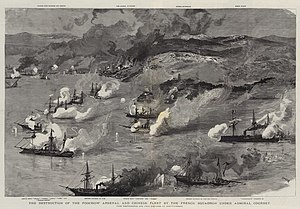

Fuzhou a řeka Min

Jednání mezi Francií a Čínou se zhroutila v polovině srpna a 22. srpna dostal Courbet rozkaz zaútočit na čínskou flotilu ve Fu-čou. V Bitva o Fuzhou (také známá jako bitva u kotvy Pagoda) 23. srpna 1884 se Francouzi pomstili za Bac Le Ambush. Během dvouhodinového střetnutí sledovaného s profesionálním zájmem neutrálními britskými a americkými plavidly (bitva byla jednou z prvních příležitostí, kdy bylo úspěšně nasazeno torpédo s nosníkem), Courbetova Letka Dálného východu zničil čínskou překonanou fujianskou flotilu a vážně poškodil Foochow Navy Yard (který byl paradoxně postaven pod vedením francouzského správce Prosper Giquel ). Za méně než hodinu bylo potopeno devět čínských lodí, včetně korvety Yangwu, vlajková loď flotily Fujian. Čínské ztráty mohly činit 3 000 mrtvých, zatímco francouzské ztráty byly minimální. Courbet poté úspěšně stáhl řeku Min na otevřené moře a zezadu zničil několik čínských pobřežních baterií, když prošel francouzskou eskadru průsmyky Min'an a Jinpai.[34]

Nepokoje v Hongkongu

Francouzský útok na Fu-čou účinně ukončil diplomatické kontakty mezi Francií a Čínou. Ačkoli žádná země nevyhlásila válku, spor by se nyní urovnal na bojišti. Zprávy o zničení fujianské flotily uvítalo vypuknutí vlastenecké vášně v Číně, která byla poznamenána útoky na cizince a cizí majetek. V Evropě panovalo s Čínou značné sympatie a Číňané byli schopni najmout jako poradce řadu důstojníků britské, německé a americké armády a námořnictva.

Vlastenecké rozhořčení se rozšířilo do britské kolonie v Hongkong. V září 1884 přístavní dělníci v Hongkongu odmítli opravit francouzskou pevnou La Galissonnière, který utrpěl poškození skořápky v srpnových námořních zásazích. Stávka se zhroutila koncem září, ale pracovníkům přístavu zabránili v obnovení činnosti další skupiny čínských pracovníků, včetně přístavních dělníků, nosičů sedadel a rikšů. Pokus britských úřadů o ochranu pracovníků přístavu před obtěžováním vyústil ve 3. října ve vážné nepokoje, během nichž byl zastřelen nejméně jeden výtržník a několik sikhských strážníků bylo zraněno. Britové měli z dobrého důvodu podezření, že rušení vyvolaly čínské orgány v provincii Kuang-tung.[35]

Francouzská okupace Keelungu

Francouzi se mezitím rozhodli vyvinout tlak na Čínu vysláním expedičního sboru na severu Formosy, aby se zmocnil Keelung a Tamsui, vykoupením neúspěchu ze dne 6. srpna a nakonec vyhráním „zástavy“, kterou hledali. Dne 1. října přistál podplukovník Bertaux-Levillain v Keelungu se silou 1 800 námořní pěchoty a přinutil Číňany stáhnout se do silných obranných pozic, které byly připraveny v okolních kopcích. Francouzská síla byla příliš malá na to, aby postoupila za Keelung, a uhelné doly Pei-tao zůstaly v čínských rukou. Mezitím, po neúčinném námořním bombardování dne 2. října, admirál Lespès zaútočil 8. října na čínskou obranu u Tamsui s 600 námořníky z vyloďovacích společností jeho letky a byl rozhodně odrazen silami pod vedením fujianského generála Sun Kaihua (孫開華). V důsledku tohoto obrácení byla francouzská kontrola nad Formosou omezena pouze na město Keelung. Tento úspěch zdaleka nedosahoval očekávání.

Blokáda Formosa

Ke konci roku 1884 byli Francouzi schopni prosadit omezenou blokádu severních formosanských přístavů Keelung a Tamsui a prefekturního hlavního města Tchaj-wanu (nyní Tainan ) a jižní přístav Takow (Kao-siung ). Na začátku ledna 1885 byl expediční sbor Formosa, nyní pod velením plukovníka Jacques Duchesne, byl podstatně posílen dvěma prapory pěchoty, čímž se jeho celková síla zvýšila na přibližně 4 000 mužů. Mezitím koncepty z Hunanská armáda a Armáda Anhui přinesl sílu obranné armády Liu Mingchuana přibližně 25 000 mužům. Přestože Francouzi na konci ledna 1885 těžce převyšovali početní převahu, dobyli na jihovýchod od Keelungu řadu menších čínských pozic, ale kvůli neustálému dešti byli v únoru nuceni zastavit útočné operace.

Blokáda uspěla částečně proto, že severní Beiyang Fleet, přikázaný Li Hongzhang, popřel pomoc na jih Flotila Nanyang. K boji s Francouzi nebyly vyslány žádné lodě Beiyang.[36] To vedlo námořnictvo k neúspěchu.[37] Nejpokročilejší lodě rezervoval pro severočínskou flotilu Li Hongzhang. Ani neuvažoval o použití této dobře vybavené flotily k útoku na Francouze, protože se chtěl ujistit, že je vždy pod jeho velením. Čínský sever a jih soupeřily a vláda byla rozdělena na různé strany.[38] Čína neměla ani jednu admirálu odpovědnou za všechna čínská námořnictva, severní a jižní čínská námořnictva nespolupracovaly. To byl důvod, proč Francie mohla během války dosáhnout kontroly nad mořem, protože nebojovala proti celému čínskému námořnictvu.[39] Tianjin Severní námořní akademie také vyčerpala jižní Čínu potenciálních námořníků, protože místo toho narukovali do severní Číny.[40]

Zátoka Shipu, Zhenhai Bay a blokáda rýže

Ačkoli expediční sbor Formosa zůstal uvězněn v Keelungu, Francouzi zaznamenali na jaře 1885 důležité úspěchy jinde. Courbetova letka byla od začátku války podstatně posílena a nyní měl k dispozici podstatně více lodí než v říjnu 1884. Na začátku února 1885 část jeho eskadry opustila Keelung, aby odvrátila hrozící pokus části Číňanů Flotila Nanyang (Flotila jižních moří) prolomit francouzskou blokádu Formosy. Dne 11. února se Courbetova pracovní skupina setkala s křižníky Kaiji, Nanchen a Nanrui, tři z nejmodernějších lodí čínské flotily poblíž Shipu Bay, doprovázené fregatou Yuyuan a kompozitní šalupa Chengqing. Číňané se rozptýlili při francouzském přístupu a zatímco tři křižníky úspěšně unikly, francouzským se podařilo chytit do pasti Yuyuan a Chengqing v Shipu Bay. V noci ze dne 14. Února v Bitva u Shipu, Francouzi zaútočili na čínská plavidla dvěma odpáleními torpéd. Během krátkého střetnutí uvnitř zálivu Yuyuan byla vážně poškozena torpédy a Chengqing byl zasažen Yuyuan 'je oheň. Obě lodě následně Číňané potopili. Vypuštění francouzského torpéda uniklo téměř bez ztráty.[41]

Courbet navázal na tento úspěch 1. března vyhledáním Kaiji, Nanchen a Nanrui, která se uchýlila k dalším čtyřem čínským válečným lodím v zátoce Zhenhai poblíž přístavu Ningbo. Courbet uvažoval o vynucení čínské obrany, ale po otestování její obrany se nakonec rozhodl střežit vstup do zátoky, aby tam nepřátelské lodě zůstaly po dobu nepřátelských akcí plněny. Krátká a neprůkazná potyčka mezi francouzským křižníkem Nielly a čínské pobřežní baterie dne 1. března umožnily čínskému generálovi Ouyangovi Lijianovi (歐陽 利 見), pověřenému obranou Ningbo, požadovat tzv.Bitva o Zhenhai „jako obranné vítězství.[42]

V únoru 1885 se Británie pod diplomatickým tlakem Číny odvolala na ustanovení zákona o zahraničním zařazení z roku 1870 a uzavřela Hongkong a další přístavy na Dálném východě pro francouzské válečné lodě. Francouzská vláda to oplatila tím, že nařídila admirálovi Courbetovi provést „rýžovou blokádu“ řeky Yangzi v naději, že se Qingský soud vyrovná provokací vážného nedostatku rýže v severní Číně. Rýžová blokáda vážně narušila námořní přepravu rýže ze Šanghaje a přinutila Číňany, aby ji přepravovali po souši, ale válka skončila, než blokáda vážně zasáhla čínskou ekonomiku.

Provoz v Tonkinu

Francouzská vítězství v deltě

Tato sekce potřebuje další citace pro ověření. (Červen 2020) (Zjistěte, jak a kdy odstranit tuto zprávu šablony) |

Mezitím francouzská armáda v Tonkinu také vyvíjela silný tlak na čínské síly a jejich spojence Černé vlajky. Na začátku září 1884 generál Millot, jehož zdraví selhalo, rezignoval na funkci generálního šéfa expedičního sboru Tonkin a byl nahrazen generálem Brière de l'Isle, nadřízeným jeho dvou velitelů brigády. Prvním úkolem Brière de l'Isleho bylo porazit velkou čínskou invazi do delty Rudé řeky. Na konci září 1884 postupovaly z Langsonu velké oddíly armády Guangxi a sondovaly do L Namc Nam údolí, oznamující jejich přítomnost přepadením francouzských dělových člunů Hache a Massue 2. října. Brière de l'Isle okamžitě zareagoval, přepravil téměř 3000 francouzských vojáků do údolí Lục Nam na palubu flotily dělových člunů a zaútočil na čínské oddíly, než se mohli soustředit. V Kampaň Kep, (2. až 15. října 1884), tři francouzské kolony pod celkovým velením generála de Négriera spadly na oddělené oddíly armády Guangxi a postupně je porazily při zásazích Lam (6. října), Kép (8. října) a Chũ (10. října). Druhá z těchto bitev byla poznamenána hořkými boji na blízko mezi francouzskými a čínskými jednotkami a de Négrierovi vojáci utrpěli těžké ztráty při útoku na opevněnou vesnici Kép. Rozzlobení vítězové po bitvě zastřelili nebo bajonetovali skóre zraněných čínských vojáků a zprávy o francouzských zvěrstvech u Kepu šokovaly veřejné mínění v Evropě. Ve skutečnosti byli vězni během čínsko-francouzské války zajati jen zřídka a Francouzi byli stejně šokováni čínským zvykem vyplácet odměnu za useknuté francouzské hlavy.

V návaznosti na tato francouzská vítězství Číňané ustoupili zpět k Bắc Lệ a Dong Songovi a de Négrier vytvořil důležité přední pozice u Kép a Chu, které ohrožovaly základnu armády Guangxi v Lang Son. Čch byl jen několik kilometrů jihozápadně od pokročilých stanovišť armády Kuang-si v Dong Song a 16. prosince silné čínské útočné oddíly přepadly dvě roty cizinecké legie těsně na východ od Čch. Ha Ho. Legionáři se probojovali z čínského obklíčení, ale utrpěli řadu obětí a museli opustit své mrtvé na bojišti. De Négrier okamžitě vychoval posily a pronásledoval Číňany, ale nájezdníci udělali dobrý ústup do Dong Song.[43]

Krátce po říjnových zásazích proti armádě Guangxi podnikl Brière de l'Isle kroky k doplnění zásob západních základen Hưng Hóa, Thái Nguyên a Tuyên Quang, které se staly stále více ohrožovány černými vlajkami Liu Yongfu a Tang Jingsong Yunnanská armáda. Dne 19. Listopadu v Bitva o Yu Oc, sloupec pro Tuyên Quanga pod velením plukovníka Jacques Duchesne byl přepaden v Yu Oc soutěska u Černých vlajek, ale dokázala se probojovat až k obléhanému stanovišti. Francouzi také zlikvidovali východní Deltu před nájezdy čínských partyzánů se sídlem v Kuang-tungu obsazením Tien Yen, Dong Trieu a dalších strategických bodů a blokádou kantonského přístavu Beihai (Pak-Hoi). Také provedli zatáčky podél dolního toku Rudé řeky, aby vytlačili annamské partyzánské skupiny ze základen blízko Hanoje. Tyto operace umožnily Brière de l'Isle soustředit většinu Tonkinského expedičního sboru kolem Chũ a Kép na konci roku 1884, aby postupoval na Long Son, jakmile bylo řečeno slovo.

Kampaň Long Son

Francouzská strategie v Tonkinu byla předmětem hořké debaty v Poslanecké sněmovně koncem prosince 1884. Ministr armády generál Jean-Baptiste-Marie Campenon tvrdil, že Francouzi by měli upevnit svoji moc nad Delta. Jeho oponenti vyzvali k totální ofenzivě, aby Číňany vyhodili ze severního Tonkinu. Debata vyvrcholila Campenonovou rezignací a jeho nahrazením jestřábovým generálem ve funkci ministra armády Jules Louis Lewal, který okamžitě nařídil Brière de l'Isleovi zajmout Lạng Sơna. Kampaň byla zahájena z francouzské přední základny v Chu a ve dnech 3. a 4. ledna 1885 zaútočil generál de Négrier a porazil podstatnou část armády Guangxi, která se soustředila kolem nedaleké vesnice Núi Bop pokusit se narušit francouzské přípravy. De Nègrierovo vítězství v Núi Bop, který vyhrál s kurzem necelého jednoho až deseti, byl svými spolupracovníky považován za nejpozoruhodnější profesionální triumf své kariéry.[44]

It took the French a month to complete their preparations for the Lạng Sơn Campaign. Finally, on 3 February 1885, Brière de l'Isle began his advance from Chu with a column of just under 7,200 troops, accompanied by 4,500 coolies. In ten days the column advanced to the outskirts of Lang Son. The troops were burdened with the weight of their provisions and equipment, and had to march through extremely difficult country. They also had to fight fierce actions to overrun stoutly defended Chinese positions, at Tây Hòa (4 February), Ahoj (5 February) and Dong Song (6 February). After a brief pause for breath at Dong Song, the expeditionary corps pressed on towards Lạng Sơn, fighting further actions at Deo Quao (9 February), and Pho Vy (11 February). On 12 February, in a costly but successful battle, the Turcos and marine infantry of Colonel Laurent Giovanninelli's 1st Brigade stormed the main Chinese defences at Bac Vie, several kilometres to the south of Lang Son.[45] On 13 February, the French column entered Lang Son which the Chinese abandoned after fighting a token rearguard action at the nearby village of Ky Lua.[46]

Siege and relief of Tuyên Quang

The capture of Lang Son allowed substantial French forces to be diverted further west to relieve the small and isolated French garrison in Tuyên Quang, which had been placed under siege in November 1884 by Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army and Tang Jingsong's Yunnan Army. The Siege of Tuyên Quang was the most evocative confrontation of the Sino-French War. The Chinese and Black Flags sapped methodically up to the French positions, and in January and February 1885 breached the outer defences with mines and delivered seven separate assaults on the breach. The Tuyên Quang garrison, 400 legionnaires and 200 Tonkinese auxiliaries under the command of chef de bataillon Marc-Edmond Dominé, beat off all attempts to storm their positions, but lost over a third of their strength (50 dead and 224 wounded) sustaining a heroic defence against overwhelming odds. By mid-February it was clear that Tuyên Quang would fall unless it was relieved immediately.[47]

Leaving de Négrier at Lang Son with the 2nd Brigade, Brière de l'Isle personally led Giovanninelli's 1st Brigade back to Hanoi, and then upriver to the relief of Tuyên Quang. The brigade, reinforced at Phu Doan on 24 February by a small column from Hung Hoa under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel de Maussion, found the route to Tuyên Quang blocked by a strong Chinese defensive position at Hòa Mộc. On 2 March 1885 Giovanninelli attacked the left flank of the Chinese defensive line. The Battle of Hòa Mộc was the most fiercely fought action of the war. Two French assaults were decisively repulsed, and although the French eventually stormed the Chinese positions, they suffered very high casualties (76 dead and 408 wounded). Nevertheless, their costly victory cleared the way to Tuyên Quang. The Yunnan Army and the Black Flags raised the siege and drew off to the west, and the relieving force entered the beleaguered post on 3 March. Brière de l'Isle praised the courage of the hard-pressed garrison in a widely quoted order of the day. ‘Today, you enjoy the admiration of the men who have relieved you at such heavy cost. Tomorrow, all France will applaud you!’[48]

Konec

Bang Bo, Ky Lua and the retreat from Lạng Sơn

Before his departure for Tuyên Quang, Brière de l'Isle ordered de Négrier to press on from Lạng Sơn towards the Chinese border and expel the battered remnants of the Guangxi Army from Tonkinese soil. After resupplying the 2nd Brigade with food and ammunition, de Négrier defeated the Guangxi Army at the Bitva o Đồng Đăng on 23 February 1885 and cleared it from Tonkinese territory. For good measure, the French crossed briefly into Guangxi province and blew up the 'Gate of China', an elaborate Chinese customs building on the Tonkin-Guangxi border. They were not strong enough to exploit this victory, however, and the 2nd Brigade returned to Langson at the end of February.[49]

By early March, in the wake of the French victories at Hoa Moc and Dong Dang, the military situation in Tonkin had reached a temporary stalemate. Giovanninelli's 1st Brigade faced Tang Qingsong's Yunnan Army around Hưng Hóa and Tuyên Quang, while de Négrier's 2nd Brigade at Lạng Sơn faced Pan Dingxin's Guangxi Army. Neither Chinese army had any realistic prospect of launching an offensive for several weeks, while the two French brigades that had jointly captured Lạng Sơn in February were not strong enough to inflict a decisive defeat on either Chinese army separately. Meanwhile, the French government was pressuring Brière de l'Isle to send the 2nd Brigade across the border into Guangxi province, in the hope that a threat to Chinese territory would force China to sue for peace. Brière de l'Isle and de Négrier examined the possibility of a campaign to capture the major Chinese military depot at Longzhou (Lung-chou, 龍州), 60 kilometres beyond the border, but on 17 March Brière de l'Isle advised the army ministry in Paris that such an operation was beyond his strength. Substantial French reinforcements reached Tonkin in the middle of March, giving Brière de l'Isle a brief opportunity to break the stalemate. He moved the bulk of the reinforcements to Hưng Hóa to reinforce the 1st Brigade, intending to attack the Yunnan Army and drive it back beyond Yen Bay. While he and Giovanninelli drew up plans for a western offensive, he ordered de Négrier to hold his positions at Lang Son.

On 23 and 24 March the 2nd Brigade, only 1,500 men strong, fought a fierce action with over 25,000 troops of the Guangxi Army entrenched near Zhennanguan on the Chinese border. The Battle of Bang Bo (named by the French from the Vietnamese pronunciation of Hengpo, a village in the centre of the Chinese position where the fighting was fiercest), is normally known as the Battle of Zhennan Pass in China. The French took a number of outworks on 23 March, but failed to take the main Chinese positions on 24 March and were fiercely counterattacked in their turn. Although the French made a fighting withdrawal and prevented the Chinese from piercing their line, casualties in the 2nd Brigade were relatively heavy (70 dead and 188 wounded) and there were ominous scenes of disorder as the defeated French regrouped after the battle. As the brigade's morale was precarious and ammunition was running short, de Négrier decided to fall back to Lang Son.[50]

The coolies abandoned the French and the French also had supply issues. The Chinese also outnumbered the French.[51] The Chinese advanced slowly in pursuit, and on 28 March de Négrier fought a battle at Ky Lua in defence of Lạng Sơn. Rested, recovered and fighting behind breastworks, the French successfully held their positions and inflicted crippling casualties on the Guangxi Army. French casualties at Ky Lua were 7 men killed and 38 wounded. The Chinese left 1,200 corpses on the battlefield, and a further 6,000 Chinese soldiers may have been wounded. The battle of Ky Lua gave a grim foretaste of the horrors of warfare on the Western Front thirty years later.[52]

Towards the end of the battle de Négrier was seriously wounded in the chest while scouting the Chinese positions. He was forced to hand over command to his senior regimental commander, Lieutenant-Colonel Paul-Gustave Herbinger. Herbinger was a noted military theoretician who had won a respectable battlefield reputation during the Franco-Prussian War, but was quite out of his depth as a field commander in Tonkin. Several French officers had already commented scathingly on his performance during the Lạng Sơn campaign and at Bang Bo, where he had badly bungled an attack on the Chinese positions.

Upon assuming command of the brigade, Herbinger panicked. Despite the evidence that the Chinese had been decisively defeated and were streaming back in disarray towards the Chinese frontier, he convinced himself that they were preparing to encircle Lạng Sơn and cut his supply line. Disregarding the appalled protests of some of his officers, he ordered the 2nd Brigade to abandon Lạng Sơn on the evening of 28 March and retreat to Chũ. The retreat from Lạng Sơn was conducted without loss and with little interference from the Chinese, but Herbinger set an unnecessarily punishing pace and abandoned considerable quantities of food, ammunition and equipment. When the 2nd Brigade eventually rallied at Chũ, its soldiers were exhausted and demoralised. Meanwhile, the Chinese general Pan Dingxin (潘鼎新), informed by sympathisers in Lạng Sơn that the French were in full retreat, promptly turned his battered army around and reoccupied Lạng Sơn on 30 March. The Chinese were in no condition to pursue the French to Chũ, and contented themselves with a limited advance to Dong Song.[53] The retreat was seen as a Chinese victory.[54]

There was also bad news for the French from the western front. On 23 March, in the Battle of Phu Lam Tao, a force of Chinese regulars and Black Flags surprised and routed a French zouave battalion that had been ordered to scout positions around Hưng Hóa in preparation for Giovanninelli's projected offensive against the Yunnan Army.[55]

Collapse of Ferry's government

Neither reverse was serious, but in the light of Herbinger's alarming reports Brière de l'Isle believed the situation to be much worse than it was, and sent an extremely pessimistic telegram back to Paris on the evening of 28 March. The political effect of this telegram was momentous. Ferry's immediate reaction was to reinforce the army in Tonkin, and indeed Brière de l'Isle quickly revised his estimate of the situation and advised the government that the front could soon be stabilised. However, his second thoughts came too late. When his first telegram was made public in Paris there was an uproar in the Chamber of Deputies. A motion of no confidence was tabled, and Ferry's government fell on 30 March.[56] 'Tonkinova aféra ', as this humiliating blow to French policy in Tonkin was immediately dubbed, effectively ended Ferry's distinguished career in French politics. He would never again become premier, and his political influence during the rest of his career would be severely limited. His successor, Henri Brisson, promptly concluded peace with China. The Chinese government agreed to implement the Tientsin Accord (implicitly recognising the French protectorate over Tonkin), and the French government dropped its demand for an indemnity for the Bắc Lệ ambush. A peace protocol ending hostilities was signed on 4 April, and a substantive peace treaty was signed on 9 June at Tianjin by Li Hongzhang and the French minister Jules Patenôtre.[57]

Japan and Russia's threat to join the war against China and the Northern fleet

Japan had taken advantage of China's distraction with France to intrigue in the Chinese protectorate state of Korea. In December 1884 the Japanese sponsored the 'Gapsin převrat ', bringing Japan and China to the brink of war. Thereafter the Qing court considered that the Japanese were a greater threat to China than the French. In January 1885 the Empress Dowager directed her ministers to seek an honourable peace with France. Secret talks between the French and Chinese were held in Paris in February and March 1885, and the fall of Ferry's ministry removed the last remaining obstacles to a peace.[58]

The Korean issue led to Japan and Russia having deteriorating relations with China, and in northern China Japan potentially threatened to join the war with France against China.[59] North China was menaced by the prospect of Japan and Russia joining in the war which led to China seeking a peace deal even though Chinese forces defeated the French on land.[54]

Li Hongzhang rejected pleas for the northern Beiyang fleet to be sent south to battle the French blockade.[36]

The Korean issue and the threat of Japan led to Li Hongzhang refusing to use the northern Beiyang fleet to fight the French who destroyed the Fuzhou fleet.[60] Li Hongzhang also wanted to personally maintain control of the fleet by keeping it in northern China and not let it slip into the control of another party.[38]

Final engagements

Ironically, while the war was being decided on the battlefields of Tonkin and in Paris, the Formosa expeditionary corps won two spectacular victories in March 1885. In a series of actions fought between 4 and 7 March Colonel Duchesne broke the Chinese encirclement of Keelung with a flank attack delivered against the east of the Chinese line, capturing the key position of La Table and forcing the Chinese to withdraw behind the Keelung River.[61] Duchesne's victory sparked a brief panic in Taipei, but the French were not strong enough to advance beyond their bridgehead. The Kampaň Keelung now reached a point of equilibrium. The French were holding a virtually impregnable defensive perimeter around Keelung but could not exploit their success, while Liu Mingchuan's army remained in presence just beyond their advanced positions.

However, the French had one card left to play. Duchesne's victory enabled Admiral Courbet to detach a marine infantry battalion from the Keelung garrison to capture the Pescadores Islands na konci března.[62] Strategically, the Pescadores campaign (1885) was an important victory, which would have prevented the Chinese from further reinforcing their army in Formosa, but it came too late to affect the outcome of the war. Future French operations were cancelled on the news of Lieutenant-Colonel Herbinger's retreat from Lạng Sơn on 28 March, and Courbet was on the point of evacuating Keelung to reinforce the Tonkin expeditionary corps, leaving only a minimum garrison at Makung in the Pescadores, when hostilities were ended in April by the conclusion of preliminaries of peace.[63]

The news of the peace protocol of 4 April did not reach the French and Chinese forces in Tonkin for several days, and the final engagement of the Sino-French War took place on 14 April 1885 at Kép, where the French beat off a half-hearted Chinese attack on their positions.[64] Meanwhile, Brière de l’Isle had reinforced the key French posts at Hưng Hóa and Chũ, and when hostilities ended in the third fortnight of April the French were standing firm against both the Guangxi and Yunnan armies.[65] Although Brière de l'Isle was planning to attack the Yunnan Army at Phu Lam Tao to avenge the defeat of 23 March, many French officers doubted whether this offensive would have succeeded. At the same time, the Chinese armies had no prospect whatsoever of driving the French from Hưng Hóa or Chũ. Militarily, the war in Tonkin ended in a stalemate.

The peace protocol of 4 April required the Chinese to withdraw their armies from Tonkin, and the French continued to occupy Keelung and the Pescadores for several months after the end of hostilities, as a surety for Chinese good faith. Admiral Courbet fell seriously ill during this occupation, and on 11 June died aboard his flagship Bayard v Makung přístav.[66] Meanwhile, the Chinese punctiliously observed the terms of the peace settlement, and by the end of June 1885 both the Yunnan and Guangxi armies had evacuated Tonkin. Liu Yongfu's Black Flag Army also withdrew from Tonkinese territory.

Continuation of insurgency

Liu Yongfu's Chinese Black Flag forces continued to harass and fight the French in Tonkin after the end of the Sino-French War.[67]

With support from China, Vietnamese and Chinese freebooters fought against the French in Lang Son in the 1890s.[68] They were labelled "pirates" by the French. The Black Flags and Liu Yongfu in China received requests for assistance from Vietnamese anti-French forces.[69][70][71][72][73] Pirate Vietnamese and Chinese were supported by China against the French in Tonkin.[74] Women from Tonkin were sold by pirates.[75] Dealers of opium and pirates of Vietnamese and Chinese origin in Tonkin fought against the French Foreign Legion.[76]

The bandits and pirates included Nung among their ranks. By adopting their clothing and hairstyle, it was possible to change identity to Nung for pirate and exile Chinese men.[77] Pirate Chinese and Nung fought against the Meo.[78] The flag pirates who fought the French were located among the Tay.[79]

In 1891 "Goldthwaite's Geographical Magazine, Volumes 1-2" said "FOUR months ago, a band of 500 pirates attacked the French residency at Chobo, in 'l‘onkin. They beheaded the French resident, ransacked and burned the town, and killed many of the people."[80] In 1906 the "Decennial Reports on the Trade, Navigation, Industries, Etc., of the Ports Open to Foreign Commerce in China and Corea, and on the Condition and Development of the Treaty Port Provinces ..., Volume 2" said "Piracy on the Tonkin border was very prevalent in the early years of the decade. Fortified frontier posts were established in 1893 by the Tonkin Customs at the most dangerous passes into China, for the purpose of repressing contraband, the importation of arms and ammunition, and specially the illicit traflic of women, children, and cattle, which the pirates raided in Tonkin and carried beyond the Chinese mountains with impunity. These posts were eventually handed over to the military authorities."[81] In 1894 "Around Tonkin and Siam" said "This, in my view, is too pessimist an estimate of the situation, a remark which also applies to the objection that these new roads facilitate the circulation of pirates. Defective as they may be, these roads must, it seems to me, be of service to cultivation and trade, and, therefore, in the long run to the pacification of the country."[82] In 1893 "The Medical World, Volume 11" said "Captain Hugot, of the Zouaves, was inclose pursuit of the fnmous Thuyet, one of the most redoubtable, ferocious, and cunning of the Black Flag (Annamite pirates) leaders, the man who prepared and executed the ambuscade at Hue. The captain was just about to seize the person of the young pretender Ham-Nghi, whom the Black Flags had recently proclaimed sovereign of Armani, when he was struck by several arrows, discharged by the body-guard of HamNghi. The wounds were all light, scarcely more than scratches, and no evil effect was feared at the time. After a few days, however, in spite of every care, the captain grew weaker, and it became apparent that he was suffering from the effects of arrow poison. He was removed as quickly and as tenderly as possible to Tanh-Hoa, where he died in horrible agony a few days later, in spite of the most scientific treatment and the most assiduous attention."— National Druggist.[83] The 1892 "The Imperial and Asiatic Quarterly Review and Oriental and Colonial Record" said "The French port of Yen Long was surprised by Chinese and Annamite pirates and the troops driven out with loss."[84][85]

French attempts to secure an alliance with Japan

The French were well aware of China's sensitivities regarding Japan, and as early as June 1883, in the wake of Rivière's death at Paper Bridge, began angling for an alliance with Japan to offset their precarious military position in Tonkin.[86] Francouzský ministr zahraničí Paul Challemel-Lacour believed that France "ought not to disdain the support which, at an appropriate moment, the attitude of Japan would be able to supply to our actions".[87] In order to court the Japanese government, France offered to support Japan's pleas for revision of the unequal treaties z Bakumatsu era, which provided extra-territoriality and advantageous tariffs to foreigners. Japan welcomed the offer of French support, but was reluctant to be drawn into a military alliance.[88] Japan was in effect quite worried of the military might China represented, at least on paper, at that time. As the situation in Annam deteriorated however, France was even more anxious to obtain Japanese help.[89]

After French difficulties in Tchaj-wan, new attempts at negotiating an alliance were made with the Minister General Campenon meeting with General Miura Goro, but Gorō remained ambiguous, encouraging France to continue to support Japan's drive for Treaty revision.[90] Hopes for an alliance were reawakened in December 1884 when a clash occurred between China and Japan in Korea, when Japan supported the Gapsin coup d'état podle Kim Ok-gyun against the pro-Chinese Korean government, prompting Jules Ferry to request the French ambassador in Japan Sienkiewicz to approach the Japanese government with an offer.[91] Sienkiewicz however remained extremely negative to the point of refraining from communicating Ferry's proposal.[92] French interest faded in 1885 as the campaign in Tonkin progressed, while, on the contrary Japanese interest increased as the Japanese government and public opinion started to favour open conflict with China.[93] The Sino-French War ended however without an alliance coming to fruition.[94]

French officers

A number of high-ranking French officers were killed in combat, including General Riviere and General Francis Garnier who were subjected to beheading.[95]

Killed in action at Bang Bo, 24 March 1885

2nd Lieutenant René Normand, 111th Line Battalion

Doctor Raynaud, 111th Line Battalion

Captain Patrick Cotter, 2nd Legion Battalion

Captain Brunet, 3rd Legion Battalion

Killed in action at Hoa Moc, 2 March 1885

Captain Tailland, killed in action at Hoa Moc, 2 March 1885

Následky

Li Hungzhang and Zeng Jizhe were key Chinese officials in the negotiations between China, France, and Vietnam. At the time, Li was the viceroy of Zhili and chief minister of Beiyang. Zeng was the Chinese ambassador to France. Li favoured a quick settlement but Zeng talked or prolonging the war. The peace treaty of June 1885 gave the French control of Annam, the contested area of Indochina. They were obliged to evacuate Formosa and the Pescadores Ostrovy[96] (which Courbet had wanted to retain as a French counterweight to British Hongkong ), but the Chinese withdrawal from Tonkin left the way clear for them to reoccupy Lạng Sơn and to advance up the Red River to Lao Cai on the Yunnan–Tonkin border. In the years that followed the French crushed a vigorous Vietnamese resistance movement and consolidated their hold on Annam and Tonkin. V roce 1887 Cochinchina, Annam a Tonkin (the territories which comprise the modern state of Vietnam) and Kambodža were incorporated into Francouzská Indočína. They were joined a few years later by Laos, ceded to France by Siam at the conclusion of the Franko-siamská válka of 1893. France dropped demands for an indemnity from China.[97][98]

Domestically, the unsatisfactory conclusion to the Sino-French War dampened enthusiasm for colonial conquest. The war had already destroyed Ferry's career, and his successor Henri Brisson also resigned in the wake of the acrimonious 'Tonkin Debate' of December 1885, in which Clemenceau and other opponents of colonial expansion nearly succeeded in securing a French withdrawal from Tonkin. In the end, the Chamber voted the 1886 credits to support the Tonkin expeditionary corps by 274 votes to 270.[99] If only three votes had gone the other way, the French would have left Tonkin. As Thomazi would later write, 'France gained Indochina very much against its own wishes.' The reverberations of the Tonkinova aféra tarnished the reputation of the proponents of French colonial expansion generally, and delayed the realisation of other French colonial projects, including the conquest of Madagascar. It was not until the early 1890s that domestic political support for colonial expansion revived in France.

As far as China was concerned, the war hastened the emergence of a strong nationalist movement, and was a significant step in the decline of the Qing empire. The loss of the Fujian fleet on 23 August 1884 was considered particularly humiliating. The Chinese strategy also demonstrated the flaws in the late Qing national defence system of independent regional armies and fleets. The military and naval commanders in the south received no assistance from Li Hongzhang's Northern Seas (Beiyang ) fleet, based in the Gulf of Zhili, and only token assistance from the Southern Seas (Nanyang ) fleet at Shanghai. The excuse given, that these forces were needed to deter a Japanese penetration of Korea, was not convincing. The truth was, that having built up a respectable steam navy at considerable expense, the Chinese were reluctant to hazard it in battle, even though concentrating their forces would have given them the best chance of challenging France's local naval superiority. The Vdova císařovny Cixi and her advisers responded in October 1885 by establishing a Navy Yamen on the model of the admiralties of the European powers, to provide unified direction of naval policy. The benefits of this reform were largely nullified by corruption, and although China acquired a number of modern ships in the decade after the Sino-French War, the Chinese navies remained handicapped by incompetent leadership. The bulk of China's steamship fleet was destroyed or captured in the Sino–Japanese War (1894–95), and for decades thereafter, China ceased to be a naval power of any importance.

Historians have judged the Qing dynasty's vulnerability and weakness to foreign imperialism in the 19th century to be based mainly on its maritime naval weakness, the historian Edward L. Dreyer said that "Meanwhile, new but not exactly modern Chinese armies suppressed the mid century rebellions, bluffed Russia into a peaceful settlement of disputed frontiers in Central Asia, and defeated the French forces on land in the Sino-French War (1884–85). However the defeat of the fleet, and the resulting threat to steamship traffic to Taiwan, forced China to conclude peace on unfavorable terms."[2]

Film

Tato část obsahuje toto znění propaguje subjekt subjektivním způsobem bez předávání skutečných informací. (Červen 2020) (Zjistěte, jak a kdy odstranit tuto zprávu šablony) |

A war movie, The War of Loong, about Feng Zicai and the victory of Chinese troops in the Sino-French conflict, was released in 2017 (https://www.imdb.com/title/tt7345928/?ref_=ttpl_pl_tt ).

Viz také

- Vztahy mezi Francií a Asií

- Franco–Siamese War z roku 1893

Reference

Citace

- ^ A b Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 (illustrated ed.). Psychologie Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Retrieved 2012-01-18. "who had been in Tonkin for only three months, took command. He immediately ordered the evacuation of Lang Són. Although Herbinger may have been retiring to the more strongly fortified positions further south, the retreat seemed to many to be the result of panic. Widely interpreted as a Chinese victory, the Qing forces were able to capture the strategic northern city of Lang Són and the surrounding territory by early April 1885. China's forces now dominated the battefield, but fighting ended on 4 April 1885 as a result of peace negotiations. China sued for peace because Britain and Germany had not offered assistance as Beijing had hoped, and Russia and Japan threatened china's northern borders. Meanwhile, China's economy was injured by the French "naval interdiction of the seaborne rich trade."197 Negotiations between Li Hongzhang and the French minister in China were concluded in June 1885. Although Li did not have to admit fault for starting the war, Beijing did recognize all of the French treaties with Annam that turned it into a French protectorate."

- ^ A b PO, Chung-yam (28 June 2013). Conceptualizing the Blue Frontier: The Great Qing and the Maritime World in the Long Eighteenth Century (PDF) (Teze). Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg. p. 11.

- ^ Jane E. Elliott (2002). Some Did it for Civilisation, Some Did it for Their Country: A Revised View of the Boxer War. Čínská univerzitní tisk. 473–. ISBN 978-962-996-066-7.

- ^ http://www.manchuarchery.org/photographs http://www.gmw.cn/01ds/2000-01/19/GB/2000^284^0^DS803.htm http://www.zwbk.org/zh-tw/Lemma_Show/100624.aspx http://www.360doc.com/content/10/0812/14/1817883_45500043.shtml „Archivovaná kopie“. Archivovány od originál dne 24. června 2016. Citováno 2. června 2016.CS1 maint: archivovaná kopie jako titul (odkaz)

- ^ Clodfelter, p. 238-239

- ^ Clodfelter, p. 238-239

- ^ Viz například Anonymous, "Named To Be Rear Admiral: Eventful and Varied Career of 'Sailor Joe' Skerrett," The New York Times, April 19, 1894.

- ^ Twitchett, Cambridge historie Číny, xi. 251; Chere, 188–90.

- ^ Eastman, p 201.

- ^ Thomazi, Conquête, 105–7

- ^ Thomazi, Conquête, 116–31

- ^ Thomazi, Conquête, 140–57

- ^ Marolles, 75–92

- ^ Eastman, 51–7

- ^ Marolles, 133–44; Lung Chang, 90–1

- ^ Eastman, 57–65

- ^ Marolles, 178–92

- ^ Huard, 26–30

- ^ Eastman, 62–9

- ^ John King Fairbank; Kwang-Ching Liu; Denis Crispin Twitchett, eds. (1980). Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911. Volume 11, Part 2 of The Cambridge History of China Series (illustrated ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 251. ISBN 0-521-22029-7. Citováno 18. ledna 2012.

For over a year prior to China's 'unofficial' declaration of war in 1884, Liu Yung-fu's 'Black Flag' forces effectively harassed the French at Tongking, at times fighting behind entrenched defences or else laying skilful ambushes.

- ^ Marolles, 193–222; Duboc, 123–39; Huard, 6–16; Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 55–8

- ^ Huard, 103–22; Loir, 13–22; Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 62–4; Conquête, 165–6

- ^ Eastman, 76–84

- ^ Eastman, 85–7

- ^ Lung Chang, 180–3 and 184–94

- ^ De Lonlay, Au Tonkin, 111–16; Duboc, 207; Huard, 164–70

- ^ Huard, 180–7 and 202–31; Thomazi, Conquête, 171–7; Histoire militaire, 68–72

- ^ Technically the Army of the Two Guangs (Guangdong and Guangxi), but invariably called the Guangxi Army in French and other European sources.

- ^ Huard, 252–76; Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 75–80

- ^ Thomazi, Conquête, 189–92

- ^ Thomazi, Conquête, 192–3

- ^ Lecomte, Guet-apens, 102–75

- ^ Duboc, 261–3; Garnot, 45–7; Loir, 184–8

- ^ Lung Chang, 280–3; Thomazi, Conquête, 204–15

- ^ Chere, Diplomacy of the Sino-French War, 108–15; JHKBRAS, 20 (1980), 54–65

- ^ A b Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 (ilustrované vydání). Psychologie Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Citováno 18. ledna 2012.

Following this setback, the Qing court officially declared war on France on 26 August 1884. On 1 October, Admiral Courbet landed at Jilong with 2,250 men, and the city fell to the French. Chinese forces continued to encircle Jilong throughout the rest of the War. Although a French blockade thwarted all subsequent Chinese efforts to send a fleet to relieve Taiwan, the French troops never succeeded in taking the riverside town of Danshui (Tamsui) in Taiwan's northwestern coastal plain, immediately north of modern-day Taipei. As a result, French control over Taiwan was limited merely to the northern coast. China's central fleet, based in Jiangsu Province, proved unable to break through Admiral Courbet's blockade of Taiwan. Although the south quickly requested assistance from the northern fleet, Li Hongzhang refused to place his own ships in danger. This decision almost guaranteed that China's coastal waters would be dominated by the French.

- ^ Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 (ilustrované vydání). Psychologie Press. p. 88. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Citováno 18. ledna 2012.

While the Chinese Army enjoyed limited victories in Annam and on Taiwan, the Chinese Navy was not so successful.

- ^ A b Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 (ilustrované vydání). Psychologie Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Citováno 18. ledna 2012.

Not surprisingly, considering Li Hongzhang's political power, many of the best and most modern ships found their way into Li's northern fleet, which never saw any action in the Sino-French conflict. In fact, fear that he might lost control over his fleet led Li to refuse to even consider sending his ships southward to aid the Fuzhou fleet against the French. Although Li later claimed that moving his fleet southward would have left northern China undefended, his decision has been criticized as a sign of China's factionalized government as well as its provincial north-south mindest.

- ^ Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 (ilustrované vydání). Psychologie Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Citováno 18. ledna 2012.

By 1883, therefore, at the outset of the Sino-French War, China's navy was poorly trained, especially in southern China. Although many of China's modern ships were state of the art, the personnel manning them were relatively unskilled: according to Rawlinson, only eight of the fourteen ship captains that saw action in the war had received any modern training at all. In addition, there was little, if any, coordination between the fleets in north and south China. The lack of a centralized admiralty commanding the entire navy meant that at any one time France opposed only a fraction of China's total fleet. This virtually assured French naval dominance in the upcoming conflict.

- ^ Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 (ilustrované vydání). Psychologie Press. p. 87. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Citováno 18. ledna 2012.

While China possessed much of the equipment for a modern navy by the early 1880s, it still did not have a sufficiently large pool of qualified sailors. One of the major training grounds during the early 1870s was at the Fuzhou Arsenal, which had hired foreign experts to conduct training classes. By the late 1870s, many of the foreigners had left Fuzhou and a new naval academy was opened at Tianjin, in northern China. This academy lured many of the best-trained Chinese sailors away from southern China.

- ^ Duboc, 274–93; Loir, 245–64; Lung Chang, 327–8; Thomazi, 220–25; Wright, 63–4

- ^ Loir, 277–9; Lung Chang, 328

- ^ Bonifacy, 7–8; Harmant, 91–112; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 149–55

- ^ Armengaud, 2–4; Bonifacy, 8–9; Harmant, 113–37; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 155–76

- ^ Armengaud, 21–4; Harmant, 157–8; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 288–98 and 304–5

- ^ Armengaud, 24–8; Bonifacy, 17–18; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 298–305

- ^ Harmant, 159–64; Thomazi, Conquête, 237–41 and 246–8; Histoire militaire, 102–3 and 107–8

- ^ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 324–9; Thomazi, Conquête, 247–8; Histoire militaire, 107–8;

- ^ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 337–49

- ^ Armengaud, 40–58; Bonifacy, 23–6; Harmant, 211–35; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 428–53 and 455

- ^ Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 (ilustrované vydání). Psychologie Press. p. 89. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Citováno 18. ledna 2012.

The Qing coury whole-heartedly supported the war, and from August to November 1884 the Chinese military prepared to enter the conflict. During the early months of 1885, the Chinese Army once again took the offensive as Beijing repeatedly ordered it to march on Tonkin. However, the shortage of supplies, poor weather, and illness devastated the Chinese troops; one 2,000 man unit reportedly lost 1,500 men to disease. This situation led one Qing military official to warn that fully one-half of all reinforcements to Annam might succumb to the elements. The focus of the fighting soon revolved around Lạng Sơn, Pan Dingxin, the Governor of Guangxi, succeeded in establishing his headquarters there by early 1885. In February 1885 a French campaign forced Pan to retreat, and the French troops soon reoccupied the town. the French forces continued the offensive, an on 23 March they temporarily occupied and then hastily torched Zhennanguan, a town on the China-Annam border, before pulling back once again to Lạng Sơn. Spurred on by the French attack, General Feng Zicai led his troops southward against General François de Négrier's forces. The situation quickly became serious for the French, as their coolies deserted, interrupting the French supply lines, and ammunition began to run short. Even though the training of the Qing troops was inferior to the French and the Chinese officer corps was poor, their absolute number were greater. This precarious situation worsened for the French when General Negrier was wounded on 28 March. Lieutenant Colonel Paul Gustave Herbinger,

- ^ Armengaud, 61–7; Bonifacy, 27–9; Harmant, 237–52; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 463–74; Thomazi, Histoire militaire, 111–12

- ^ Armengaud, 74–6; Bonifacy, 36–8 and 39–40; Harmant, 274–300; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 501–12

- ^ A b Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Modern Chinese warfare, 1795–1989 (ilustrované vydání). Psychologie Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Citováno 18. ledna 2012.

who had been in Tonkin for only three months, took command. He immediately ordered the evacuation of Lang Són. Although Herbinger may have been retiring to the more strongly fortified positions further south, the retreat seemed to many to be the result of panic. Widely interpreted as a Chinese victory, the Qing forces were able to capture the strategic northern city of Lang Són and the surrounding territory by early April 1885. China's forces now dominated the battefield, but fighting ended on 4 April 1885 as a result of peace negotiations. China sued for peace because Britain and Germany had not offered assistance as Beijing had hoped, and Russia and Japan threatened china's northern borders. Meanwhile, China's economy was injured by the French "naval interdiction of the seaborne rich trade."197 Negotiations between Li Hongzhang and the French minister in China were concluded in June 1885. Although Li did not have to admit fault for starting the war, Beijing did recognize all of the French treaties with Annam that turned it into a French protectorate.

- ^ Bonifacy, 37–8; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 329–30 and 515–16; Lung Chang, 340

- ^ Thomazi, Conquête, 258–61

- ^ Huard, 800–12; Lung Chang, 369–71; Thomazi, Conquête, 261–2

- ^ Eastman, 196–9; Lecomte, Lang-Son, 405–8 and 531–6

- ^ John King Fairbank (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Late Chʻing, 1800–1911, pt. 2. Cambridge University Press. pp. 251–. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3.

- ^ John King Fairbank (1978). The Cambridge History of China: Late Chʻing, 1800–1911, pt. 2. Cambridge University Press. str. 252–. ISBN 978-0-521-22029-3.

- ^ Garnot, 147–72

- ^ Garnot, 179–95; Loir, 291–317

- ^ Garnot, 195–206

- ^ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 524–6

- ^ Lecomte, Lang-Son, 513–24

- ^ Garnot, 214–23; Loir, 338–45

- ^ Lessard 2015, pp. 58-9.

- ^ Douglas Porch (11 July 2013). Counterinsurgency: Exposing the Myths of the New Way of War. Cambridge University Press. str. 52–. ISBN 978-1-107-02738-1.

- ^ David G. Marr (1971). Vietnamese Anticolonialism, 1885–1925. University of California Press. str. 72–. ISBN 978-0-520-04277-3.

- ^ Paul Rabinow (1 December 1995). French Modern: Norms and Forms of the Social Environment. University of Chicago Press. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-226-70174-5.

- ^ Le Tonkin: ou la France dans l'Extrême-Orient 1884, Hinrichsen (page 64)

- ^ Henri Frey (1892). Pirates et rebelles au Tonkin: nos soldats au Yen-Thé. Hachette.

- ^ "1898 ATM7 INDOCHINE TONKIN DE THAM PIRATES YEN THE ANNAMITES NHA GUE - eBay". www.ebay.com. Citováno 28. března 2018.

- ^ Benerson Little (2010). Lov pirátů: Boj proti pirátům, lupičům a mořským lupičům od starověku po současnost. Potomac Books, Inc., str. 205–. ISBN 978-1-59797-588-9.

- ^ Micheline Lessard (24. dubna 2015). Obchodování s lidmi v koloniálním Vietnamu. Routledge. str. 22–. ISBN 978-1-317-53622-2.

- ^ Jean-Denis G.G. Lepage (11. prosince 2007). Francouzská cizinecká legie: Ilustrovaná historie. McFarland. str. 72–. ISBN 978-0-7864-3239-4.

- ^ Jean-Pascal Bassino; Jean-Dominique Giacometti; Kōnosuke Odaka; Suzanne Ruth Clarková (2000). Kvantitativní hospodářské dějiny Vietnamu, 1900–1990: mezinárodní workshop. Institut ekonomického výzkumu, univerzita Hitotsubashi. p. 375.

- ^ John Colvin (1996). Sopka pod sněhem: Vo Nguyen Giap. Knihy o kvartetu. p. 76. ISBN 978-0-7043-7100-2.

- ^ Jean Michaud (19. dubna 2006). Historický slovník národů masivu jihovýchodní Asie. Strašák Press. str. 232–. ISBN 978-0-8108-6503-7.

- ^ Geografický časopis Goldthwaite. Wm. M. & J.C. Goldthwaite. 1891. str. 362–.

- ^ Čína. Hai guan zong shui wu si shu (1906). Desetileté zprávy o obchodu, navigaci, průmyslových odvětvích atd., O přístavech otevřených zahraničnímu obchodu v Číně a Koreji a o stavu a vývoji provincií přístavu Smlouvy ... Statistický odbor generálního inspektora cel. str. 464–.

- ^ Kolem Tonkin a Siam. Chapman & Hall. 1894. str.73 –.

- ^ Lékařský svět. Roy Jackson. 1893. str. 283–.

- ^ Asijská recenze. Východ západ. 1892. str. 234–.

- ^ Císařský a asijský čtvrtletní přehled a orientální a koloniální záznam. Orientální institut. 1892. str.1 –.

- ^ Richard Sims Francouzská politika vůči Bakufu a Meiji Japan 1854–95 str.122

- ^ Richard Sims Francouzská politika vůči Bakufu a Meiji Japan 1854–95 str.123

- ^ Richard Sims Francouzská politika vůči Bakufu a Meiji Japan 1854–95 str. 125

- ^ Richard Sims Francouzská politika vůči Bakufu a Meiji Japan 1854–95 str.128

- ^ Richard Sims Francouzská politika vůči Bakufu a Meiji Japan 1854–95 str.130

- ^ Richard Sims Francouzská politika vůči Bakufu a Meiji Japan 1854–95 s. 131

- ^ Richard Sims Francouzská politika vůči Bakufu a Meiji Japan 1854–95 str. 136

- ^ Richard Sims Francouzská politika vůči Bakufu a Meiji Japan 1854–95 str. 138-139

- ^ Richard Sims Francouzská politika vůči Bakufu a Meiji Japan 1854–95 str.142

- ^ Elliott 2002, str. 195.

- ^ Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Moderní čínská válka, 1795–1989 (ilustrované vydání). Psychologie Press. p. 90. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Citováno 18. ledna 2012.

Prostřednictvím tohoto mírového dítěti Francie souhlasila s evakuací svých vojsk z Tchaj-wanu a Pescadores výměnou za to, že Čína přijala, že Annam se stal francouzským protektorátem. . .

- ^ Bruce A. Elleman (2001). Moderní čínská válka, 1795–1989 (ilustrované vydání). Psychologie Press. p. 92. ISBN 0-415-21474-2. Citováno 18. ledna 2012.

Čína nemusela Francii platit odškodnění

- ^ Burlette, Julia Alayne Grenier (2007). Francouzský vliv v zámoří: Vzestup a pád koloniální Indočíny (PDF) (Diplomová práce). p. 25. Archivovány od originál (PDF) dne 22. července 2010.

- ^ Huard, 1 113–74; Thomazi, Conquête, 277–82

Zdroje

- Armengaud, J., Lang-Son: Journal des opérations qui ont précédé et suivi la prize de cette citadelle (Paříž, 1901)

- Bonifacy, Prozatímní kolekce des peintures chinoises reprezentativní rozmanité epizody francouzského chinoise z let 1884–1885 (Hanoj, 1931)

- Chere, L. M., „Hongkongské nepokoje z října 1884: důkazy čínského nacionalismu?“, Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 20 (1980), 54–65 [1]

- Chere, L. M., Diplomacie čínsko-francouzské války (1883–1885): Globální komplikace nehlášené války (Notre Dame, 1988)

- Clodfelter, M. (2017). Warfare and Armed Conflicts: A Statistical Encyclopedia of Casualty and Other Figures, 1492-2015 (4. vydání). Jefferson, Severní Karolína: McFarland.

- Duboc, E., Trente cinq mois de campagne en Chine, au Tonkin (Paříž, 1899)

- Eastman, L., Trůn a mandarinky: Hledání politiky v Číně během čínsko-francouzské diskuse (Stanford, 1984)

- Elleman, B., Modern Chinese Warfare, 1795–1989 (New York, 2001) [2]

- Garnot, L'expédition française de Formose, 1884–1885 (Paříž, 1894)

- Harmant, J., La verité sur la retraite de Lang-Son (Paříž, 1892)

- Huard, L., La guerre du Tonkin (Paříž, 1887)

- Lecomte, J., Le guet-apens de Bac-Lé (Paříž, 1890)

- Lecomte, J., Lang-Son: boje, retraite et négociations (Paříž, 1895)

- Loir, M., L'escadre de l'amiral Courbet (Paříž, 1886)

- Lung Chang [龍 章], Yueh-nan yu Chung-fa chan-cheng [越南 與 中法 戰爭, Vietnam a čínsko-francouzská válka] (Taipei, 1993)

- Marolles, Vice-amiral de, La dernière campagne du Commandant Henri Rivière (Paříž, 1932)

- Randier, J., La Royale (La Falaise, 2006) ISBN 2-35261-022-2

- Bernard, H., L'Amiral Henri Rieunier (1833–1918) Ministre de la Marine - La Vie extraordinaire d'un grand marin (Biarritz, 2005)

- Thomazi, A., La conquête de l'Indochine (Paříž, 1934)

- Thomazi, A., Histoire militaire de l'Indochine française (Hanoj, 1931)

Další čtení

- Caruana, J .; Koehler, R. B. & Millar, Steve (2001). „Otázka 20/00: Operace francouzského námořnictva na východě 1858–1885“. Warship International. Mezinárodní organizace pro námořní výzkum. XXXVIII (3): 238–239. ISSN 0043-0374.

- James F. Roche; L. L. Cowen (1884). Francouzi ve Foochowě. ŠANGHAJ: Vytištěno v kanceláři „Celestial Empire“. str.49. Citováno 6. července 2011.(Originál z University of California)

- Olender, Piotr (2012). Sino-francouzská námořní válka, 1884–1885. Knihy MMP.