Marie Antoinette - Marie Antoinette

| Marie Antoinette | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Portrét od Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, 1778 | |||||

| Královna choť Francie | |||||

| Držba | 10. května 1774 - 21. září 1792 | ||||

| narozený | 2. listopadu 1755 Palác Hofburg, Vídeň, Rakouské arcivévodství, Svatá říše římská | ||||

| Zemřel | 16. října 1793 (ve věku 37) Place de la Révolution, Paříž, Francouzská první republika | ||||

| Pohřbení | 21. ledna 1815 | ||||

| Manželka | |||||

| Problém | |||||

| |||||

| Dům | Habsburg-Lotrinsko | ||||

| Otec | František I., císař svaté říše římské | ||||

| Matka | Marie Terezie z Rakouska | ||||

| Náboženství | Římský katolicismus | ||||

| Podpis | |||||

Erb Marie Antoinetty z Rakouska | |||||

Marie Antoinette (/ˌ…ntwəˈnɛt,ˌɒ̃t-/,[1] Francouzština:[maʁi ɛtwanɛt] (![]() poslouchat); narozený Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2. listopadu 1755 - 16. října 1793) byla poslední královna Francie před francouzská revoluce. Narodila se arcivévodkyně Rakouska a byla předposledním dítětem a nejmladší dcerou Císařovna Marie Terezie a Císař František I.. Stala se dauphine z Francie v květnu 1770 ve věku 14 let po jejím sňatku s Louis-Auguste Dědic francouzského trůnu. Dne 10. května 1774 nastoupil její manžel na trůn jako Ludvík XVI. A stala se královnou.

poslouchat); narozený Maria Antonia Josepha Johanna; 2. listopadu 1755 - 16. října 1793) byla poslední královna Francie před francouzská revoluce. Narodila se arcivévodkyně Rakouska a byla předposledním dítětem a nejmladší dcerou Císařovna Marie Terezie a Císař František I.. Stala se dauphine z Francie v květnu 1770 ve věku 14 let po jejím sňatku s Louis-Auguste Dědic francouzského trůnu. Dne 10. května 1774 nastoupil její manžel na trůn jako Ludvík XVI. A stala se královnou.

Pozice Marie Antoinette u soudu se zlepšila, když po osmi letech manželství začala mít děti. U Francouzů se však mezi lidmi stávala stále více nepopulární libely obvinil ji z toho, že je rozmařilejší, promiskuitní a chová sympatie k francouzským vnímaným nepřátelům - zejména k jejímu rodnému Rakousku - a jejím dětem z nelegitimy. Falešná obvinění Záležitost s diamantovým náhrdelníkem poškodila její pověst dále. Během revoluce se stala známou jako Madame Déficit protože finanční krizi země byla přičítána jejím bohatým výdajům a jejímu odporu vůči sociálním a finančním reformám v roce 2006 Turgot a Necker.

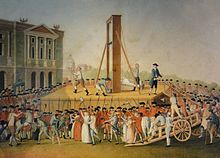

Několik událostí bylo spojeno s Marií Antoinette během revoluce poté, co vláda uvalila královskou rodinu do domácího vězení Tuilerijský palác v říjnu 1789. Červen 1791 se pokusil let do Varennes a její role v Válka první koalice mělo katastrofální dopad na francouzský lidový názor. Na 10. srpna 1792, útok na Tuileries přinutil královskou rodinu uchýlit se k Shromáždění, a byli uvězněni v Temple Prison 13. srpna. Dne 21. Září 1792 monarchie byla zrušena. Ludvík XVI. Byl popraven gilotina dne 21. ledna 1793. Proces u Marie Antoinetty začal dne 14. října 1793 a o dva dny později byla odsouzena Revoluční tribunál velezrady a popraven, také gilotinou, na Place de la Révolution.

Časný život (1755–1770)

Maria Antonia se narodila 2. listopadu 1755 v Palác Hofburg ve Vídni v Rakousku. Byla nejmladší dcerou Císařovna Marie Terezie, vládce Habsburská říše a její manžel František I., císař svaté říše římské.[2] Její kmotři byli Joseph I. a Mariana Victoria, Portugalský král a královna; Arcivévoda Joseph a arcivévodkyně Maria Anna jednali jako zmocněnci pro svou novorozenou sestru.[3][4] Maria Antonia se narodila Dušičky, katolický den smutku, a během jejího dětství se místo toho oslavovaly její narozeniny den předtím Všech svatých, kvůli konotacím data. Krátce po jejím narození byla umístěna do péče vychovatelky císařských dětí, hraběnky von Brandeis.[5] Maria Antonia byla vychována společně se svou sestrou, Maria Carolina, která byla o tři roky starší a se kterou měla celoživotní blízký vztah.[6] Maria Antonia měla s matkou obtížný, ale nakonec milující vztah,[7] který o ní hovořil jako o „malé madame Antoine“.

Maria Antonia strávila formativní léta mezi palácem Hofburg a Schönbrunn, císařské letní sídlo ve Vídni,[4] kde se 13. října 1762, když jí bylo sedm, setkala Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, O dva měsíce mladší a zázračné dítě.[8][4][5][9] Navzdory soukromému doučování, které absolvovala, byly výsledky jejího vzdělávání méně než uspokojivé.[10] Ve věku 10 let neuměla správně psát v němčině ani v jazyce běžně používaném u soudu, jako je francouzština nebo italština,[4] a rozhovory s ní byly strnulé.[11][4]

Pod výukou Christoph Willibald Gluck, Z Maria Antonia se vyvinula dobrá muzikantka. Naučila se hrát na harfa,[10] the cembalo a flétna. Zpívala během večerních setkání rodiny, protože měla krásný hlas.[12] Také vynikala v tanci, měla „vynikající“ chování a milovala panenky.[13]

Dauphine z Francie (1770–1774)

V návaznosti na Sedmiletá válka a Diplomatická revoluce z roku 1756 se císařovna Marie Terezie rozhodla ukončit nepřátelství se svým dlouholetým nepřítelem králem Louis XV Francie. Jejich společná touha zničit ambice Pruska a Velké Británie a zajistit konečný mír mezi jejich zeměmi je vedla k uzavření spojenectví manželstvím: 7. února 1770 Ludvík XV formálně požádal o ruku Marie Antonie pro jeho nejstarší přeživší vnuk a dědic, Louis-Auguste, duc de Berry a Dauphin z Francie.[4]

Maria Antonia se formálně vzdala svých práv Habsburg domén a dne 19. dubna byla ženatý na základě plné moci francouzskému Dauphinovi na Augustiniánský kostel ve Vídni se svým bratrem Arcivévoda Ferdinand stojí za Dauphinem.[14][15][4] Dne 14. Května potkala svého manžela na okraji les Compiègne. Po svém příjezdu do Francie přijala francouzskou verzi svého jména: Marie Antoinette. Další slavnostní svatba se konala 16. Května 1770 v Palác ve Versailles a po slavnostech den skončil rituální povlečení.[16][17] Dlouhodobý neúspěch páru suverénní manželství sužovalo pověst Louis-Auguste a Marie Antoinetty na příštích sedm let.[18][19]

Počáteční reakce na manželství Marie Antoinetty a Louis-Auguste byla smíšená. Na jedné straně byl Dauphine krásný, osobitý a obyčejní lidé ho měli rádi. Její první oficiální vystoupení v Paříži dne 8. června 1773 mělo obrovský úspěch. Na druhou stranu měli ti, kdo se stavěli proti spojenectví s Rakouskem, obtížný vztah s Marií Antoinettou, stejně jako ostatní, kteří ji neměli rádi z osobních nebo malicherných důvodů.[20]

Madame du Barry se ukázalo jako nepříjemný nepřítel nového dauphine. Byla milenkou Ludvíka XV. A měla na něj značný politický vliv. V roce 1770 byla nápomocna při vypuzení Étienne François, Duc de Choiseul, který pomohl zorganizovat francouzsko-rakouské spojenectví a manželství Marie Antoinetty,[21] a ve vyhnanství své sestry, vévodkyně de Gramont, jedné z čekajících dám Marie Antoinetty. Marie Antoinetta byla tety jejího manžela přesvědčena, aby odmítly uznat du Barryho, což někteří považovali za politickou chybu, která ohrožovala zájmy Rakouska u francouzského soudu. Matka Marie Antoinette a rakouský velvyslanec ve Francii, Comte de Mercy-Argenteau, který zaslal tajné zprávy císařovny o chování Marie Antoinetty, tlačil na Marii Antoinettu, aby promluvila s Madame du Barry, s čímž s nechutí souhlasila, že to udělá na Nový rok 1772.[22][23] Pouze jí řekla: „Ve Versailles je dnes hodně lidí“, ale to stačilo madame du Barry, která byla s tímto uznáním spokojena, a krize pominula.[24] Dva dny po smrti Ludvíka XV. V roce 1774 deportoval Ludvík XVI. Du Barryho do Abbaye de Pont-aux-Dames v r. Meaux, což potěšilo jak jeho manželku, tak tety.[25][26][27][28][29] O dva a půl roku později, na konci října 1776, skončilo vyhnanství madam du Barry a bylo jí umožněno vrátit se do svého milovaného zámku v Louveciennes, ale nikdy jí nebylo dovoleno vrátit se do Versailles.[30]

Raná léta (1774–78)

Po smrti Ludvíka XV. Dne 10. května 1774 nastoupil Dauphin na trůn jako král Ludvík XVI Francie a Navarra s Marií Antoinette jako jeho královnou. Na začátku měla nová královna omezený politický vliv se svým manželem, který s podporou svých dvou nejdůležitějších ministrů, hlavního ministra Maurepas a ministr zahraničí Vergennes, zablokovala několik jejích kandidátů v přijímání důležitých pozic, včetně Choiseul.[31][32] Královna hrála rozhodující roli v potupě a vyhnanství nejmocnějších ministrů Ludvíka XV., duc d'Aiguillon.[33][34][35]

Dne 24. května 1774, dva týdny po smrti Ludvíka XV., Král obdaroval svou manželku Petit Trianon, malý zámek ve Versailles, který postavil Ludvík XV pro svou milenku, Madame de Pompadour. Louis XVI dovolil Marii Antoinette, aby ji zrekonstruovala, aby vyhovovala jejímu vlastnímu vkusu; brzy kolovaly pověsti, že stěny omítla zlatem a diamanty.[36]

Královna těžce utrácela za módu, luxus a hazard, ačkoli země čelila vážné finanční krizi a populace trpěla. Rose Bertinová vytvořil pro ni šaty a účesy jako poufs, vysoký až tři stopy (90 cm), a panache (sprška peří). Ona a její soud také přijaly anglickou módu šatů vyrobených z indienne (materiál zakázaný ve Francii od roku 1686 do roku 1759 na ochranu místního francouzského vlněného a hedvábného průmyslu) perkál a mušelín.[37][38] V době, kdy Válka s moukou z roku 1775 řada nepokojů (kvůli vysoké ceně mouky a chleba) poškodila její pověst u široké veřejnosti. Pověst Marie Antoinetty nakonec nebyla o nic lepší než reputace oblíbených předchozích králů. Mnoho Francouzů ji začalo obviňovat z ponižující ekonomické situace, což naznačuje, že neschopnost země splácet svůj dluh byla výsledkem jejího plýtvání korunovými penězi.[39] Matka Marie Antoinetty, Marie Terezie, ve své korespondenci vyjádřila znepokojení nad výdajovými návyky své dcery a citovala občanské nepokoje, které to začalo způsobovat.[40]

Již v roce 1774 se Marie Antoinetta začala spřátelit s některými ze svých mužských obdivovatelů, jako například baron de Besenval, duc de Coigny, a Hrabě Valentin Esterházy,[41][42] a také navázal hluboké přátelství s různými dámami u soudu. Nejznámější bylo Marie-Louise, princezna de Lamballe, související s královskou rodinou prostřednictvím jejího manželství s Penthièvrova rodina. Dne 19. září 1774 jmenovala svého dozorce její domácnosti,[43][44] schůzku, kterou brzy přenesla ke svému novému oblíbenci, vévodkyně z Polignacu.

V roce 1774 převzala záštitu nad svým bývalým učitelem hudby, německým operním skladatelem Christoph Willibald Gluck, který zůstal ve Francii až do roku 1779.[45][46]

Mateřství, změny u soudu, intervence v politice (1778–1781)

Uprostřed atmosféry vlny libely, Svatá říše římská Císař Josef II přijel do Francie inkognito pod jménem Comte de Falkenstein na šestitýdenní návštěvu, během níž intenzivně cestoval po Paříži a hostoval ve Versailles. Se svou sestrou a jejím manželem se seznámil dne 18. Dubna 1777 v Château de la Muette, a upřímně promluvil se svým švagrem, zvědavý, proč královské manželství nebylo naplněno, a dospěl k závěru, že neexistuje žádná překážka manželských vztahů páru, kromě nezájmu královny a neochoty krále se namáhat .[47] V dopise svému bratrovi Leopold, Velkovévoda Toskánska, Joseph II je popsal jako „pár úplných lumpů“.[48] Prozradil Leopoldovi, že nezkušený - tehdy ještě jen 22letý - Ludvík XVI. Mu svěřil postup, který podnikal v manželské posteli; říká, že Ludvík XVI. „představí člena“, ale poté „zůstane tam, aniž by se pohyboval asi dvě minuty,“ stáhne se, aniž by dokončil akt, a „nabídne dobrou noc“.[49]

Návrhy, kterými Louis trpěl fimóza, kterému se ulevilo obřízka, byly zdiskreditovány.[50] Po Josephově intervenci však bylo manželství v srpnu 1777 nakonec naplněno.[51] O osm měsíců později, v dubnu 1778, bylo podezření, že královna je těhotná, což bylo oficiálně oznámeno 16. května.[52] Dcera Marie Antoinette, Marie-Thérèse Charlotte, Madame Royale, se narodil ve Versailles dne 19. prosince 1778.[7][53][54] Otcovství dítěte bylo napadeno v libely stejně jako všechny její děti.[55][56]

Uprostřed těhotenství královny došlo ke dvěma událostem, které měly zásadní dopad na její pozdější život: návrat jejího přítele a milence, švédského diplomata Počítat Axel von Fersen[57] na dva roky do Versailles a nárok jejího bratra na trůn Bavorsko, napadené habsburskou monarchií a Pruskem.[58] Marie Antoinette prosila svého manžela, aby se za Rakousko přimlouvala za Francouze. The Mír těšínský, podepsaná 13. května 1779, ukončila krátký konflikt, kdy královna na naléhání své matky uvalila francouzskou mediaci a Rakousko získalo území nejméně 100 000 obyvatel - silný ústup od rané francouzské pozice, která byla vůči Rakousku nepřátelská. To částečně vyvolávalo dojem, že se královna postavila na stranu Rakouska proti Francii.[59][60]

Mezitím královna začala zavádět změny v soudních zvycích. Někteří z nich se setkali s nesouhlasem starší generace, jako je upuštění od silného líčení a populární širokopásmový kufry.[62] Nová móda volala po jednodušším ženském vzhledu, typickém nejprve pro rustikální vzhled župan à la polonaise styl a později gaulle, vrstvené mušelínové šaty, které Marie Antoinette nosila v roce 1783 Vigée-Le Brun portrét.[63] V roce 1780 se začala účastnit amatérských her a muzikálů v divadle postaveném pro ni Richard Mique na Petit Trianon.[64]

Splátky francouzského dluhu zůstaly obtížným problémem, který dále prohloubily Vergennes a také pobídnutí Marie Antoinette[Citace je zapotřebí ] Louis XVI zapojit Francii do války ve Velké Británii s ní Severoamerické kolonie. Primární motiv pro zapojení královny do politických záležitostí v tomto období může mít pravděpodobně více společného se soudním factionalismem než jakýkoli skutečný zájem z její strany o samotnou politiku.[65] ale hrála důležitou roli při pomoci americká revoluce zajištěním rakouské a ruské podpory Francii, což vedlo k vytvoření neutrální ligy, která zastavila útok Velké Británie, a nerozhodným zvážením nominace Philippe Henri, markýz de Ségur jako ministr války a Charles Eugène Gabriel de La Croix, markýz de Castries jako ministr námořnictva v roce 1780, který pomáhal George Washington porazit Brity v americká revoluční válka, který skončil v roce 1783.[66]

V roce 1783 hrála královna při jmenování rozhodující roli Charles Alexandre de Calonne, blízký přítel Polignaců, as Generální kontrolor financí a baron de Breteuil jako Ministr královské domácnosti, což z něj dělá možná nejsilnějšího a nejkonzervativnějšího ministra vlády.[Citace je zapotřebí ] Výsledkem těchto dvou nominací bylo, že vliv Marie Antoinetty se stal ve vládě prvořadým a noví ministři odmítli jakoukoli zásadní změnu struktury starého režimu. Více než to, dekret de Ségura, ministra války, vyžadující čtyři čtvrtletí šlechta jako podmínka pro jmenování důstojníků zablokovala přístup občanů na důležité pozice v ozbrojených silách a zpochybnila koncept rovnosti, jedné z hlavních stížností a příčin francouzské revoluce.[67][68]

Druhé těhotenství Marie Antoinetty skončilo a potrat počátkem července 1779, jak potvrzují dopisy mezi královnou a její matkou, i když někteří historici věřili, že mohla zaznamenat krvácení související s nepravidelným menstruačním cyklem, které si spletla se ztraceným těhotenstvím.[69] Její třetí těhotenství bylo potvrzeno v březnu 1781 a dne 22. října porodila Louis Joseph Xavier François Dauphin z Francie.

Císařovna Marie Terezie zemřela 29. listopadu 1780 ve Vídni. Marie Antoinette se obávala, že smrt její matky ohrozí francouzsko-rakouské spojenectví (a nakonec i sebe), ale její bratr, Josef II., Císař svaté říše římské, napsal jí, že nemá v úmyslu alianci prolomit.[70]

Druhá návštěva Josefa II., Která se uskutečnila v červenci 1781 s cílem potvrdit francouzsko-rakouské spojenectví a také vidět jeho sestru, byla poznamenána falešnými pověstmi[56] že Marie Antoinette mu poslala peníze z francouzské pokladnice.[71][72]

Klesající popularita (1782–1785)

Navzdory obecným oslavám nad zrozením Dauphina byl politický vliv Marie Antoinetty, jaký byl, velmi přínosný pro Rakousko.[73] Během Konvice válka, ve kterém se její bratr Joseph pokusil otevřít Řeka Scheldt pro námořní plavbu se Marii Antoinettě podařilo uložit Vergennesovi povinnost vyplatit Rakousku obrovské finanční vyrovnání. Nakonec se královně podařilo získat podporu jejího bratra Velká Británie v americká revoluce a neutralizovala francouzské nepřátelství vůči jeho spojenectví s Ruskem.[74][75]

V roce 1782, po vychovatelce královských dětí, princezna de Guéméné, zkrachovala a rezignovala, Marie Antoinette jmenovala svého oblíbence, vévodkyně z Polignacu, do polohy.[76] Toto rozhodnutí se setkalo s nesouhlasem soudu, protože vévodkyně byla považována za příliš skromný porod, než aby mohla zaujímat tak vznešené postavení. Na druhou stranu král i královna plně věřili paní de Polignac, poskytli jí třináctipokojový byt ve Versailles a zaplatili jí dobře.[77] Celá rodina Polignaců těžila z královské laskavosti v titulech a pozicích, ale její náhlé bohatství a bohatý životní styl pobouřily většinu aristokratických rodin, které nesnášely dominanci Polignaců u soudu, a také podporovaly rostoucí populární nesouhlas Marie Antoinetty, většinou v Paříži.[78] De Mercy napsal císařovně: „Je téměř nevysvětlitelné, že za tak krátkou dobu měla královská laskavost přinést rodině takové ohromné výhody“.[79]

V červnu 1783 bylo oznámeno nové těhotenství Marie Antoinette, ale v noci z 1. na 2. listopadu, jejích 28. narozenin, potratila.

Počet Axel von Fersen, po svém návratu z Ameriky v červnu 1783, byl přijat do královniny soukromé společnosti. Stále existovaly tvrzení, že tito dva byli romanticky zapletení,[80] ale protože většina jejich korespondence byla ztracena nebo zničena, neexistují žádné přesvědčivé důkazy.[81] V roce 2016 Telegrafní Henry Samuel oznámil, že vědci z francouzského Výzkumného střediska pro ochranu sbírek (CRCC) „pomocí nejmodernějších rentgenových paprsků a různých infračervených skenerů“ dešifrovali dopis od ní, který aféru prokázal.[82]

V této době brožury popisující fraškovou sexuální deviaci včetně královny a jejích přátel u soudu rostly v celé zemi. The Portefeuille d’un talon rouge byl jedním z prvních, včetně královny a řady dalších šlechticů v politickém prohlášení odsuzujícím nemorální praktiky soudu. Postupem času se tyto začaly stále více soustředit na královnu. Popsali milostná setkání s celou řadou postav, od vévodkyně de Polignac až po Ludvíka XV. Jak se tyto útoky zvyšovaly, byly spojeny s odporem veřejnosti k jejímu spojení s konkurenčním rakouským národem. Veřejně bylo naznačeno, že její domnělé chování se naučilo u soudu soupeřícího národa, zejména lesbismu, který byl znám jako „německý zlozvyk“.[83] Její matka opět vyjádřila obavy o bezpečnost své dcery a začala využívat rakouského velvyslance ve Francii, Comte de Mercy, poskytnout informace o bezpečnosti a pohybech Marie Antoinetty.[84]

V roce 1783 byla královna zaneprázdněna jejím vytvořením “osada ", rustikální útočiště postavené jejím oblíbeným architektem, Richard Mique, podle návrhů malíře Hubert Robert.[85] Jeho vytvoření však způsobilo další rozruch, když se jeho cena stala všeobecně známou.[86][87] Osada však nebyla výstředností Marie Antoinetty. V té době bylo v módě, aby šlechtici měli na svých pozemcích rekreace malých vesnic. Ve skutečnosti byl design zkopírován z designu princ de Condé. Bylo také podstatně menší a méně složité než mnoho jiných šlechticů.[88] Kolem tentokrát nashromáždila knihovnu 5000 knih. Ti, kteří se jí často věnovali, byli nejčtenější, i když také ráda četla historii.[89][90] Sponzorovala umění, zejména hudbu, a také podporovala některé vědecké snahy, povzbuzovala a byla svědkem prvního zahájení Montgolfière, a horkovzdušný balón.[91]

Dne 27. dubna 1784, Beaumarchais hra Figarova svatba měl premiéru v Paříži. Hra byla původně králem zakázána kvůli jejímu negativnímu zobrazení šlechty a hra byla nakonec povolena k veřejnému provedení kvůli podpoře královny a její ohromné popularitě u soudu, kde o ní tajně četla Marie Antoinette. Tato hra byla katastrofou pro obraz monarchie a aristokracie. Inspirovalo to Mozart je Le Nozze di Figaro, která měla premiéru ve Vídni 1. května 1786.[92]

Dne 24. října 1784 koupil Ludvík XVI., Jeho převzetím barona de Breteuila, Ludvík XVI Château de Saint-Cloud z duc d'Orléans jménem jeho manželky, kterou chtěla kvůli jejich rozrůstající se rodině. Chtěla mít možnost vlastnit svůj vlastní majetek. Jeden, který byl ve skutečnosti její, aby pak měl pravomoc jej odkázat „kterémukoli z mých dětí si přeji“; výběr dítěte, o kterém si myslela, že ho může použít, spíše než procházení patriarchálními dědickými zákony nebo rozmary. Bylo navrženo, že náklady by mohly být pokryty z jiných prodejů, například z prodeje zámek Trompette v Bordeaux.[93] To bylo nepopulární, zejména u těch frakcí šlechty, které se nelíbily královně, ale také u rostoucího procenta populace, která nesouhlasila s francouzskou královnou, která by vlastnila soukromou rezidenci. Nákup společnosti Saint-Cloud tak ještě více poškodil obraz veřejnosti o královně. Vysoká cena zámku, téměř 6 milionů livres, plus značné dodatečné náklady na vymalování, zajistily, že na splácení podstatného dluhu Francie šlo mnohem méně peněz.[94][95]

Dne 27. března 1785 porodila Marie Antoinette druhého syna, Louis Charles, který nesl titul duc de Normandie.[96] Skutečnost, že k porodu došlo přesně devět měsíců po Fersenově návratu, neunikla pozornosti mnoha, což vedlo k pochybnostem o původu dítěte a ke znatelnému poklesu reputace královny ve veřejném mínění.[97] Většina životopisců Marie Antoinetty a Ludvíka XVII věří, že mladý princ byl biologickým synem Ludvíka XVI., Včetně Stefan Zweig a Antonia Fraser, kteří věří, že Fersen a Marie Antoinette byli skutečně romanticky zapleteni.[98][99][100][101][102][103][104][105] Fraser také poznamenal, že datum narození se dokonale shoduje se známou manželskou návštěvou krále.[56] Dvořané ve Versailles si ve svých denících poznamenali, že datum koncepce dítěte ve skutečnosti dokonale odpovídalo období, kdy král a královna trávili mnoho času společně, ale tyto podrobnosti byly ignorovány uprostřed útoků na královninu postavu.[106] Tato podezření na nelegitimitu spolu s pokračujícím zveřejňováním libely a nikdy nekončící kavalkády soudních intrik, akce Josefa II Konvice válka, nákup společností Saint-Cloud a Záležitost s diamantovým náhrdelníkem ve spojení, aby se prudce obrátil lidový názor proti královně, a ve francouzské psychice se rychle zakořenil obraz nemorální, utrácející cizí královny s prázdnou hlavou.[107]

Druhá dcera, její poslední dítě, Marie Sophie Hélène Béatrix, Madame Sophie, se narodil 9. července 1786 a do 19. června 1787 žil jen jedenáct měsíců.

Čtyři živě narozené děti Marie Antoinetty byly:

- Marie-Thérèse-Charlotte, Madame Royale (19. prosince 1778 - 19. října 1851)

- Louis-Joseph-Xavier-François, Dauphin (22. října 1781 - 4. června 1789)

- Louis-Charles, Dauphin po smrti svého staršího bratra, budoucího titulárního krále Ludvíka XVII. ve Francii (27. března 1785 - 8. června 1795)

- Sophie-Hélène-Béatrix, zemřel v dětství (9. července 1786 - 19. června 1787)

Předehra k revoluci: skandály a neúspěch reforem (1786–1789)

Skandál s diamantovým náhrdelníkem

Marie Antoinette začala ve své roli francouzské královny opouštět své bezstarostnější činnosti a stále více se angažovala v politice.[108] Veřejným projevem své pozornosti výchově a péči o své děti se královna snažila zlepšit zpustlý obraz, který získala v roce 1785 z „Affair s diamantovým náhrdelníkem ", ve kterém ji veřejné mínění falešně obvinilo z trestné účasti na podvodu klenotníků Boehmera a Bassenge v ceně drahého diamantového náhrdelníku, který původně vytvořili pro madame du Barry. Hlavními aktéry skandálu byli Kardinál de Rohan, princ de Rohan-Guéméné, velký francouzský Almoner, a Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy, hraběnka de La Motte, potomek nemanželského dítěte Henry II Francie z Dům Valois. Marie Antoinette hluboce neměla ráda Rohana od doby, kdy byl jako dítě francouzským velvyslancem ve Vídni. Navzdory jeho vysoké administrativní pozici u soudu mu nikdy neřekla ani slovo. Dalšími účastníky byla Nicole Lequay, alias Baronne d'Oliva, prostitutka, která vypadala jako Marie Antoinette; Rétaux de Villette padělatel; Alessandro Cagliostro, italský dobrodruh; a Comte de La Motte, manžel Jeanne de Valois. Paní de La Motte přiměla Rohana, aby koupil náhrdelník jako dárek pro Marii Antoinettu, aby získal královninu přízeň.

Když byla aféra objevena, byli všichni zúčastnění (kromě de La Motte a Rétaux de Villette, kterým se podařilo uprchnout) zatčeni, souzeni, odsouzeni a buď uvězněni nebo vyhoštěni. Mme de La Motte byla odsouzena na doživotí do vězení Nemocnice Pitié-Salpêtrière, který sloužil také jako vězení pro ženy. Soudě Parlement, Rohan byl shledán nevinným vůči jakémukoli provinění a bylo mu dovoleno opustit Bastillu. Marie Antoinette, která trvala na zatčení kardinála, byla zasažena těžká osobní rána, stejně jako monarchie, a navzdory skutečnosti, že vinné strany byly souzeny a odsouzeny, se aféra ukázala být velmi škodlivá pro její pověst, což nikdy se z toho nevzpamatoval.[Citace je zapotřebí ]

Selhání politických a finančních reforem

Král, který trpěl akutním depresivním stavem, začal hledat radu od své manželky. Ve své nové roli a se zvyšující se politickou mocí se královna pokusila zlepšit nepříjemnou situaci, která panovala mezi shromážděním a králem.[109] Tato změna postavení královny signalizovala konec vlivu Polignaců a jejich dopad na finance koruny.

Pokračující zhoršování finanční situace i přes škrty královské družiny a soudní výdaje nakonec přinutily krále, královnu a ministra financí, Calonne, na naléhání Vergennes, svolat zasedání Shromáždění významných osobností, po přestávce 160 let. Shromáždění se konalo za účelem zahájení nezbytných finančních reforem, avšak Parlement odmítl spolupracovat. První setkání se konalo dne 22. února 1787, devět dní po smrti Vergennes dne 13. února. Marie Antoinette se schůzky nezúčastnila a její nepřítomnost vyústila v obvinění, že se královna pokouší podkopat její účel.[110][111] Shromáždění selhalo. Neprošel žádnými reformami a místo toho upadl do vzpoury králi. Na naléhání královny, Louis XVI propustil Calonne dne 8. dubna 1787.[109]

1. května 1787 Étienne Charles de Loménie de Brienne, arcibiskup z Toulouse a jeden z politických spojenců královny, byl jmenován králem na její naléhání, aby nahradil Calonne, nejprve jako Generální kontrolor financí a poté jako předseda vlády. Začal zavádět další škrty u soudu, zatímco se pokoušel obnovit královskou absolutní moc oslabenou parlamentem.[112] Brienne nedokázala zlepšit finanční situaci, a protože byl spojencem královny, toto selhání nepříznivě ovlivnilo její politické postavení. Pokračující špatné finanční klima v zemi mělo za následek 25. května rozpuštění shromáždění významných osobností kvůli jeho neschopnosti fungovat a nedostatek řešení byl viněn královně.[67]

Finanční problémy Francie byly výsledkem kombinace faktorů: několik drahých válek; velká královská rodina, jejíž výdaje hradil stát; a neochota většiny členů privilegovaných vrstev, aristokracie a duchovenstva, pomoci uhradit náklady na vládu z jejich vlastních kapes tím, že se vzdá některých svých finančních privilegií. V důsledku veřejného vnímání, že sama zničila národní finance, dostala Marie Antoinette v létě 1787 přezdívku „Madame Déficit“.[113] I když za ni nemohla jediná chyba finanční krize, Marie Antoinetta byla největší překážkou jakéhokoli významného reformního úsilí. Hrála rozhodující roli v hanbě reformních ministrů financí, Turgot (v roce 1776) a Jacques Necker (první propuštění v roce 1781). Při zohlednění tajných výdajů královny byly soudní výdaje mnohem vyšší než oficiální odhad 7% státního rozpočtu.[114]

Královna se pokusila bránit propagandou zobrazující ji jako starostlivou matku, zejména na obraze od Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun vystavoval na Royal Académie Salon de Paris v srpnu 1787, ukazující ji se svými dětmi.[115][116] Zhruba ve stejné době Jeanne de Valois-Saint-Rémy uprchla z vězení a uprchla do Londýna, kde zveřejnila škodlivé pomluvy týkající se její údajné milostné aféry s královnou.[117]

Politická situace v roce 1787 se zhoršila, když na naléhání Marie Antoinetty Parlement byl vyhoštěn do Troyes 15. srpna. Dále se zhoršovalo, když se Ludvík XVI. Pokusil použít a lit de Justice dne 11. listopadu uložit právní předpisy. The nový Duc d'Orléans veřejně protestoval proti královským činům a následně byl vyhoštěn na svůj majetek v Villers-Cotterêts.[118] Květnové edikty vydané dne 8. května 1788 byly rovněž proti veřejnosti a parlamentu. Nakonec 8. srpna oznámil Ludvík XVI. Svůj úmysl přivést zpět Generální statky, tradiční zvolený zákonodárce země, který nebyl svolán od roku 1614.[119]

Zatímco od konce roku 1787 až do své smrti v červnu 1789 bylo hlavním zájmem Marie Antoinetty pokračující zhoršování zdraví Dauphina, který trpěl tuberkulóza,[120] byla přímo zapojena do exilu EU Parlement, květnové edikty a oznámení týkající se generálních stavů. Podílela se na Radě krále, první královně, která to udělala za více než 175 let (od té doby Marie Medicejská byl pojmenován Šéfkuchař du Conseil du Roi, mezi 1614 a 1617), a ona dělala hlavní rozhodnutí v zákulisí a v Královské radě.

Marie Antoinette se zasloužila o obnovení Jacques Necker jako ministryně financí 26. srpna, populární krok, i když sama měla obavy, že by to šlo proti ní, kdyby se Neckerovi nepodařilo reformovat finance země. Přijala Neckerův návrh na zdvojnásobení zastoupení Třetí majetek (tiers état) ve snaze ověřit moc aristokracie.[121][122]

V předvečer zahájení stavovského generála se královna zúčastnila mše oslavující její návrat. Jakmile se otevřelo 5. května 1789, došlo k roztržce mezi demokraty Třetí majetek (skládající se z měšťanů a radikálních aristokratů) a konzervativní šlechty Druhý majetek rozšířila a Marie Antoinette věděla, že její soupeř, Duc d'Orléans, který dával lidem během zimy peníze a chléb, bude davem uznáván, a to na její úkor.[123]

Smrt Dauphina 4. června, která hluboce zasáhla jeho rodiče, byla francouzským lidem prakticky ignorována,[124] kteří se místo toho připravovali na příští schůzi generálních stavů a doufali v řešení chlebové krize. Jelikož se třetí stav prohlásil a národní shromáždění a vzal Přísaha na tenisovém kurtu, and as people either spread or believed rumors that the queen wished to bathe in their blood, Marie Antoinette went into mourning for her eldest son.[125] Her role was decisive in urging the king to remain firm and not concede to popular demands for reforms. In addition, she showed her determination to use force to crush the forthcoming revolution.[126][127]

French Revolution before Varennes (1789–91)

The situation escalated on 20 June as the Third Estate, which had been joined by several members of the clergy and radical nobility, found the door to its appointed meeting place closed by order of the king. It thus met at the tennis court in Versailles and took the Přísaha na tenisovém kurtu not to separate before it had given a constitution to the nation.

On 11 July at Marie Antoinette's urging Necker was dismissed and replaced by Breteuil, the queen's choice to crush the Revolution with mercenary Swiss troops under the command of one of her favorites, Pierre Victor, baron de Besenval de Brünstatt.[128][129][130] At the news, Paris was besieged by riots that culminated in the útok Bastily dne 14. července.[131][132]15. července Gilbert du Motier, markýz de Lafayette was named commander-in-chief of the newly formed Garde nationale.[133][134]

In the days following the storming of the Bastille, for fear of assassination, and ordered by the king, the emigration of members of the high aristocracy began on 17 July with the departure of the hrabě d'Artois, the Condés, cousins of the king,[135] and the unpopular Polignacs. Marie Antoinette, whose life was as much in danger, remained with the king, whose power was gradually being taken away by the Ústavodárné národní shromáždění.[133][136][137]

The abolition of feudal privileges podle Ústavodárné národní shromáždění on 4 August 1789 and the Deklarace práv člověka a občana (La Déclaration des Droits de l'Homme et du Citoyen), drafted by Lafayette with the help of Thomas Jefferson and adopted on 26 August, paved the way to a Konstituční monarchie (4 September 1791 – 21 September 1792).[138][139] Despite these dramatic changes, life at the court continued, while the situation in Paris was becoming critical because of bread shortages in September. On 5 October, a crowd from Paris descended upon Versailles and forced the royal family to move to the Tuilerijský palác in Paris, where they lived under a form of house arrest under the watch of Lafayette's Garde Nationale, while the Comte de Provence and jeho žena were allowed to reside in the Petit Luxembourg, where they remained until they went into exile on 20 June 1791.[140]

Marie Antoinette continued to perform charitable functions and attend religious ceremonies, but dedicated most of her time to her children.[141] She also played an important political, albeit not public, role between 1789 and 1791 when she had a complex set of relationships with several key actors of the early period of the French Revolution. One of the most important was Necker, the Prime Minister of Finances (Premier ministre des finances).[142] Despite her dislike of him, she played a decisive role in his return to the office. She blamed him for his support of the Revolution and did not regret his resignation in 1790.[143][144]

Lafayette, one of the former military leaders in the American War of Independence (1775–83), served as the warden of the royal family in his position as commander-in-chief of the Garde Nationale. Despite his dislike of the queen—he detested her as much as she detested him and at one time had even threatened to send her to a convent—he was persuaded by the mayor of Paris, Jean Sylvain Bailly, to work and collaborate with her, and allowed her to see Fersen a number of times. He even went as far as exiling the Duke of Orléans, who was accused by the queen of fomenting trouble. His relationship with the king was more cordial. As a liberal aristocrat, he did not want the fall of the monarchy but rather the establishment of a liberal one, similar to that of the Spojené království, based on cooperation between the king and the people, as was to be defined in the Constitution of 1791.

Despite her attempts to remain out of the public eye, Marie Antoinette was falsely accused in the libelles of having an affair with Lafayette, whom she loathed,[145] and, as was published in Le Godmiché Royal ("The Royal Dildo"), and of having a sexual relationship with the English baroness Lady Sophie Farrell of Bournemouth, a well-known lesbian of the time. Publication of such calumnies continued to the end, climaxing at her trial with an accusation of incest with her son. There is no evidence to support the accusations.

Mirabeau

A significant achievement of Marie Antoinette in that period was the establishment of an alliance with Honoré Gabriel Riqueti, Comte de Mirabeau, the most important lawmaker in the assembly. Like Lafayette, Mirabeau was a liberal aristocrat. He had joined the Third estate and was not against the monarchy, but wanted to reconcile it with the Revolution. He also wanted to be a minister and was not immune to corruption. On the advice of Mercy, Marie Antoinette opened secret negotiations with him and both agreed to meet privately at the Château de Saint-Cloud on 3 July 1790, where the royal family was allowed to spend the summer, free of the radical elements who watched their every move in Paris.[146][147] At the meeting, Mirabeau was much impressed by the queen, and remarked in a letter to Auguste Marie Raymond d'Arenberg, Comte de la Marck, that she was the only person the king had by him: La Reine est le seul homme que le Roi ait auprès de Lui.[148] An agreement was reached turning Mirabeau into one of her political allies: Marie Antoinette promised to pay him 6000 livres per month and one million if he succeeded in his mission to restore the king's authority.[149]

The only time the royal couple returned to Paris in that period was on 14 July to attend the Fête de la Fédération, an official ceremony held at the Champ de Mars in commemoration of the fall of the Bastille one year earlier. At least 300,000 persons participated from all over France, including 18,000 national guards, with Talleyrand, biskup z Autun, celebrating a mass at the autel de la Patrie ("altar of the fatherland"). The king was greeted at the event with loud cheers of "Long live the king!", especially when he took the oath to protect the nation and to enforce the laws voted by the Constitutional Assembly. There were even cheers for the queen, particularly when she presented the Dauphin to the public.[150][151]

Mirabeau sincerely wanted to reconcile the queen with the people, and she was happy to see him restoring much of the king's powers, such as his authority over foreign policy, and the right to declare war. Over the objections of Lafayette and his allies, the king was given a suspensive veto allowing him to veto any laws for a period of four years. With time, Mirabeau would support the queen, even more, going as far as to suggest that Louis XVI "adjourn" to Rouen or Compiègne.[152] This leverage with the Assembly ended with the death of Mirabeau in April 1791, despite the attempt of several moderate leaders of the Revolution to contact the queen to establish some basis of cooperation with her.

Občanská ústava duchovenstva

In March 1791 Papež Pius VI odsoudil Občanská ústava duchovenstva, reluctantly signed by Louis XVI, which reduced the number of bishops from 132 to 93, imposed the election of bishops and all members of the clergy by departmental or district assemblies of electors, and reduced the Pope's authority over the Church. Religion played an important role in the life of Marie Antoinette and Louis XVI, both raised in the Roman Catholic faith. The queen's political ideas and her belief in the absolute power of monarchs were based on France's long-established tradition of the božské právo králů.[Citace je zapotřebí ] On 18 April, as the royal family prepared to leave for Saint-Cloud to attend Easter mass celebrated by a refractory priest, a crowd, soon joined by the Garde Nationale (disobeying Lafayette's orders), prevented their departure from Paris, prompting Marie Antoinette to declare to Lafayette that she and her family were no longer free. This incident fortified her in her determination to leave Paris for personal and political reasons, not alone, but with her family. Even the king, who had been hesitant, accepted his wife's decision to flee with the help of foreign powers and counter-revolutionary forces.[153][154][155] Fersen and Breteuil, who represented her in the courts of Europe, were put in charge of the escape plan, while Marie Antoinette continued her negotiations with some of the moderate leaders of the French Revolution.[156][157]

Flight, arrest at Varennes and return to Paris (21–25 June 1791)

There had been several plots designed to help the royal family escape, which the queen had rejected because she would not leave without the king, or which had ceased to be viable because of the king's indecision. Once Louis XVI finally did commit to a plan, its poor execution was the cause of its failure. In an elaborate attempt known as the Let do Varennes dosáhnout monarchista pevnost Montmédy, some members of the royal family were to pose as the servants of an imaginary "Mme de Korff", a wealthy Russian baroness, a role played by Louise-Elisabeth de Croÿ de Tourzel, governess of the royal children.

After many delays, the escape was ultimately attempted on 21 June 1791, but the entire family was arrested less than twenty-four hours later at Varennes and taken back to Paris within a week. The escape attempt destroyed much of the remaining support of the population for the king.[158][159]

Upon learning of the capture of the royal family, the Ústavodárné národní shromáždění sent three representatives, Antoine Barnave, Jérôme Pétion de Villeneuve a Charles César de Fay de La Tour-Maubourg to Varennes to escort Marie Antoinette and her family back to Paris. On the way to the capital they were jeered and insulted by the people as never before. The prestige of the French monarchy had never been at such a low level. During the trip, Barnave, the representative of the moderate party in the Assembly, protected Marie Antoinette from the crowds, and even Pétion took pity on the royal family. Brought safely back to Paris, they were met with total silence by the crowd. Thanks to Barnave, the royal couple was not brought to trial and was publicly osvobozen of any crime in relation with the attempted escape.[160][161]

Marie Antoinette's first Lady of the Bedchamber, Mme Campan, wrote about what happened to the queen's hair on the night of 21–22 June, "...in a single night, it had turned white as that of a seventy-year old woman." (En une seule nuit ils étaient devenus blancs comme ceux d'une femme de soixante-dix ans.)[162]

Radicalization of the Revolution after Varennes (1791–92)

After their return from Varennes and until the útok Tuileries on 10 August 1792, the queen, her family and entourage were held under tight surveillance by the Garde Nationale in the Tuileries, where the royal couple was guarded night and day. Four guards accompanied the queen wherever she went, and her bedroom door had to be left open at night. Her health also began to deteriorate, thus further reducing her physical activities.[163][164]

On 17 July 1791, with the support of Barnave and his friends, Lafayette's Garde Nationale zahájil palbu on the crowd that had assembled on the Champ de Mars to sign a petition demanding the depozice krále. The estimated number of those killed varies between 12 and 50. Lafayette's reputation never recovered from the event and, on 8 October, he resigned as commander of the Garde Nationale. Their enmity continuing, Marie Antoinette played a decisive role in defeating him in his aims to become the mayor of Paris in November 1791.[165]

As her correspondence shows, while Barnave was taking great political risks in the belief that the queen was his political ally and had managed, despite her unpopularity, to secure a moderate majority ready to work with her, Marie Antoinette was not considered sincere in her cooperation with the moderate leaders of the French Revolution, which ultimately ended any chance to establish a moderate government.[166] Moreover, the view that the unpopular queen was controlling the king further degraded the royal couple's standing with the people, which the Jakobíni successfully exploited after their return from Varennes to advance their radical agenda to abolish the monarchy.[167] This situation lasted until the spring of 1792.[168][169]

Marie Antoinette continued to hope that the military coalition of European kingdoms would succeed in crushing the Revolution. She counted most on the support of her Austrian family. After the death of her brother Joseph in 1790, his successor, Leopold, was willing to support her to a limited degree.[Citace je zapotřebí ] Upon Leopold's death in 1792, his son, Francis, a conservative ruler, was ready to support the cause of the French royal couple more vigorously because he feared the consequences of the French Revolution and its ideas for the monarchies of Europe, particularly, for Austria's influence in the continent.[Citace je zapotřebí ]

Barnave had advised the queen to call back Mercy, who had played such an important role in her life before the Revolution, but Mercy had been appointed to another foreign diplomatic position[kde? ] and could not return to France. At the end of 1791, ignoring the danger she faced, the Princezna de Lamballe, who was in London, returned to the Tuileries. As to Fersen, despite the strong restriction imposed on the queen, he was able to see her a final time in February 1792.[170]

Events leading to the abolition of the monarchy on 10 August 1792

Leopold's and Francis II's strong action on behalf of Marie Antoinette led to France's declaration of war on Austria on 20 April 1792. This resulted in the queen being viewed as an enemy, although she was personally against Austrian claims to French territories on European soil. That summer, the situation was compounded by multiple defeats of the French armies by the Austrians, in part because Marie Antoinette passed on military secrets to them.[171] In addition, at the insistence of his wife, Louis XVI vetoed several measures that would have further restricted his power, earning the royal couple the nicknames "Monsieur Veto" and "Madame Veto",[172][173] nicknames then prominently featured in different contexts, including La Carmagnole.

Barnave remained the most important advisor and supporter of the queen, who was willing to work with him as long as he met her demands, which he did to a large extent. Barnave and the moderates comprised about 260 lawmakers in the new Legislative Assembly; the radicals numbered around 136, and the rest around 350. Initially, the majority was with Barnave, but the queen's policies led to the radicalization of the Assembly and the moderates lost control of the legislative process. The moderate government collapsed in April 1792 to be replaced by a radical majority headed by the Girondins. The Assembly then passed a series of laws concerning the Church, the aristocracy, and the formation of new national guard units; all were vetoed by Louis XVI. While Barnave's faction had dropped to 120 members, the new Girondin majority controlled the legislative assembly with 330 members. The two strongest members of that government were Jean Marie Roland, who was minister of interior, and General Dumouriez, the minister of foreign affairs. Dumouriez sympathized with the royal couple and wanted to save them but he was rebuffed by the queen.[174][175]

Marie Antoinette's actions in refusing to collaborate with the Girondins, in power between April and June 1792, led them to denounce the treason of the Austrian comity, a direct allusion to the queen. Po Madame Roland sent a letter to the king denouncing the queen's role in these matters, urged by the queen, Louis XVI disbanded[Citace je zapotřebí ] the government, thus losing his majority in the Assembly. Dumouriez resigned and refused a post in any new government. At this point, the tide against royal authority intensified in the population and political parties, while Marie Antoinette encouraged the king to veto the new laws voted by the Legislative Assembly in 1792.[176] In August 1791, the Prohlášení Pillnitz threatened an invasion of France. This led in turn to a French declaration of war in April 1792, which led to the Francouzské revoluční války and to the events of August 1792, which ended the monarchy.[177]

On 20 June 1792, "a mob of terrifying aspect" broke into the Tuileries, made the king wear the červená kapota (red Phrygian cap) to show his loyalty to the Republic, insulted Marie Antoinette, accusing her of betraying France, and threatened her life. In consequence, the queen asked Fersen to urge the foreign powers to carry out their plans to invade France and to issue a manifesto in which they threatened to destroy Paris if anything happened to the royal family. The Brunswickský manifest, issued on 25 July 1792, triggered the events of 10 August[178] when the approach of an armed mob on its way to the Tuileries Palace forced the royal family to seek refuge at the Legislative Assembly. Ninety minutes later, the palace was invaded by the mob, who massacred the Švýcarské gardy.[179][180] On 13 August the royal family was imprisoned in the tower of the Chrám v Marais under conditions considerably harsher than those of their previous confinement in the Tuileries.[181]

A week later, several of the royal family's attendants, among them the Princezna de Lamballe, were taken for interrogation by the Pařížská komuna. Převedeno do La Force vězení, after a rapid judgment, Marie Louise de Lamballe byl savagely killed 3. září. Her head was affixed on a pike and paraded through the city to the Temple for the queen to see. Marie Antoinette was prevented from seeing it, but fainted upon learning of it.[182][183]

On 21 September 1792, the fall of the monarchy was officially declared and the Národní shromáždění became the governing body of the French Republic. The royal family name was downgraded to the non-royal "Kapety ". Preparations began for the trial of the king in a court of law.[184]

Louis XVI's trial and execution

Charged with undermining the První francouzská republika, Louis XVI was separated from his family and tried in December. He was found guilty by the Convention, led by the Jacobins who rejected the idea of keeping him as a hostage. On 15 January 1793, by a majority of one vote, that of Philippe Égalité, he was condemned to death by guillotine and executed on 21 January 1793.[185][186]

Marie Antoinette in the Temple

The queen, now called "Widow Capet", plunged into deep mourning. She still hoped her son Louis-Charles, whom the exiled Comte de Provence, Louis XVI's brother, had recognized as Louis XVI's successor, would one day rule France. The royalists and the refractory clergy, including those preparing the insurrection in Vendée, supported Marie Antoinette and the return to the monarchy. Throughout her imprisonment and up to her execution, Marie Antoinette could count on the sympathy of conservative factions and social-religious groups which had turned against the Revolution, and also on wealthy individuals ready to bribe republican officials to facilitate her escape;[187] These plots all failed. While imprisoned in the Tower of the Temple, Marie Antoinette, her children, and Élisabeth were insulted, some of the guards going as far as blowing smoke in the ex-queen's face. Strict security measures were taken to assure that Marie Antoinette was not able to communicate with the outside world. Despite these measures, several of her guards were open to bribery and a line of communication was kept with the outside world.[Citace je zapotřebí ]

After Louis' execution, Marie Antoinette's fate became a central question of the National Convention. While some advocated her death, others proposed exchanging her for French prisoners of war or for a ransom from the Holy Roman Emperor. Thomas Paine advocated exile to America.[188] In April 1793, during the Vláda teroru, a Výbor pro veřejnou bezpečnost dominuje Robespierre was formed, and men such as Jacques Hébert began to call for Marie-Antoinette's trial. Do konce května Girondins had been chased from power.[189] Calls were also made to "retrain" the eight-year-old Louis XVII, to make him pliant to revolutionary ideas. To carry this out, Louis Charles was separated from his mother on 3 July after a struggle during which his mother fought in vain to retain her son, who was handed over to Antoine Simon, a cobbler and representative of the Pařížská komuna. Until her removal from the Temple, Marie Antoinette spent hours trying to catch a glimpse of her son, who, within weeks, had been made to turn against her, accusing his mother of wrongdoing.[190]

Conciergerie

On the night of 1 August, at 1:00 in the morning, Marie Antoinette was transferred from the Temple to an isolated cell in the Conciergerie as 'Prisoner n° 280'. Leaving the tower she bumped her head against the překlad of a door, which prompted one of her guards to ask her if she was hurt, to which she answered, "No! Nothing now can hurt me."[191] This was the most difficult period of her captivity. She was under constant surveillance, with no privacy. The "Carnation Plot" (Le complot de l'œillet), an attempt to help her escape at the end of August, was foiled due to the inability to corrupt all the guards.[192] She was attended by Rosalie Lamorlière, who took care of her as much as she could. At least once she received a visit by a Catholic priest.[193][194]

Trial and execution (14–16 October 1793)

Marie Antoinette was tried by the Revolutionary Tribunal on 14 October 1793. Some historians believe the outcome of the trial had been decided in advance by the Committee of Public Safety around the time the Carnation Plot (fr ) byl odkryt.[195] She and her lawyers were given less than one day to prepare her defense. Among the accusations, many previously published in the libelles, were: orchestrating orgies in Versailles, sending millions of livres of treasury money to Austria, planning the massacre of the gardes françaises (National Guards) in 1792,[196] declaring her son to be the new king of France, and incest, a charge made by her son Louis Charles, pressured into doing so by the radical Jacques Hébert who controlled him. This last accusation drew an emotional response from Marie Antoinette, who refused to respond to this charge, instead of appealing to all mothers present in the room; their reaction comforted her since these women were not otherwise sympathetic to her.[197][198]

Early on 16 October, Marie Antoinette was declared guilty of the three main charges against her: depletion of the national treasury, conspiracy against the internal and external security of the State, and velezrada because of her intelligence activities in the interest of the enemy; the latter charge alone was enough to condemn her to death.[199] At worst, she and her lawyers had expected life imprisonment.[200] In the hours left to her, she composed a letter to her sister-in-law, Madame Élisabeth, affirming her clear conscience, her Catholic faith, and her love and concern for her children. The letter did not reach Élisabeth.[201] Her will was part of the collection of papers of Robespierre found under his bed and were published by Edme-Bonaventure Courtois.[202][203]

Preparing for her execution, she had to change clothes in front of her guards. She put on a plain white dress, white being the color worn by widowed queens of France. Her hair was shorn, her hands bound painfully behind her back and she was put on a rope leash. Unlike her husband, who had been taken to his execution in a carriage (carrosse), she had to sit in an open cart (charrette) for the hour it took to convey her from the Conciergerie přes rue Saint-Honoré thoroughfare to reach the guillotine erected in the Place de la Révolution (the present-day Place de la Concorde ).[204] She maintained her composure, despite the insults of the jeering crowd. A ústavní priest was assigned to her to hear her final confession. He sat by her in the cart, but she ignored him all the way to the scaffold.[205][206]

Marie Antoinette was guillotined at 12:15 p.m. on 16 October 1793.[207][208] Her last words are recorded as, "Pardonnez-moi, monsieur. Je ne l’ai pas fait exprès" or "Pardon me, sir, I did not do it on purpose", after accidentally stepping on her executioner's shoe.[209] Her head was one of which Marie Tussaud was employed to make masky smrti.[210] Her body was thrown into an neoznačený hrob v Madeleine cemetery located close by in rue d'Anjou. Because its capacity was exhausted the cemetery was closed the following year, on 25 March 1794.[211]

Both Marie Antoinette's and Louis XVI's bodies were exhumed on 18 January 1815, during the Bourbon restaurování, když Comte de Provence ascended the newly reestablished throne as Ludvík XVIII, King of France and of Navarre. Christian burial of the royal remains took place three days later, on 21 January, in the necropolis of French kings at the Bazilika sv. Denise.[212]

Dědictví

For many revolutionary figures, Marie Antoinette was the symbol of what was wrong with the old regime in France. The onus of having caused the financial difficulties of the nation was placed on her shoulders by the revolutionary tribunal,[213] and under the new republican ideas of what it meant to be a member of a nation, her Austrian descent and continued correspondence with the competing nation made her a traitor.[214] The people of France saw her death as a necessary step toward completing the revolution. Furthermore, her execution was seen as a sign that the revolution had done its work.[215]

Marie-Antoinette is also known for her taste for fine things, and her commissions from famous craftsmen, such as Jean-Henri Riesener, suggest more about her enduring legacy as a woman of taste and patronage. For instance, a writing table attributed to Riesener, now located at Waddesdon Manor, bears witness to Marie-Antoinette's desire to escape the oppressive formality of court life, when she decided to move the table from the Queen's boudoir de la Meridienne at Versailles to her humble interior, the Petit Trianon. Her favourite objects filled her small, private chateau and reveal aspects of Marie-Antoinette's character that have been obscured by satirical political prints, such as those in Les Tableaux de la Révolution.[216]

Long after her death, Marie Antoinette remains a major historical figure linked with conservatism, the katolický kostel, wealth, and fashion. She has been the subject of a number of books, films, and other media. Politically engaged authors have deemed her the quintessential representative of třídní konflikt, západní aristokracie a absolutismus. Some of her contemporaries, such as Thomas Jefferson, attributed to her the start of the francouzská revoluce.[217]

V populární kultuře

Fráze "Let them eat cake " is often attributed to Marie Antoinette, but there is no evidence that she ever uttered it, and it is now generally regarded as a journalistic cliché.[218] This phrase originally appeared in Book VI of the first part of Jean-Jacques Rousseau autobiografické dílo Les Confessions, finished in 1767 and published in 1782: "Enfin Je me rappelai le pis-aller d'une grande Princesse à qui l'on disait que les paysans n'avaient pas de pain, et qui répondit: Qu'ils mangent de la brioche" ("Finally I recalled the stopgap solution of a great princess who was told that the peasants had no bread, and who responded: 'Let them eat brioška'"). Rousseau ascribes these words to a "great princess", but the purported writing date precedes Marie Antoinette's arrival in France. Some think that he invented it altogether.[219]

In the United States, expressions of gratitude to France for its help in the americká revoluce included naming a city Marietta, Ohio v roce 1788.[220] Her life has been the subject of many films, such as the 2006 film Marie Antoinette.[221]

In 2020, a silk shoe that belonged to her will be sold in an auction in the Palace of Versailles starting $11.800.[222]

Děti

| název | Portrét | Životnost | Poznámky |

|---|---|---|---|

| Marie Thérèse Charlotte Madame Royale |  | 19 December 1778 – 19 October 1851 | Married her cousin, Louis Antoine, vévoda z Angoulême, the eldest son of the future Charles X Francie. |

| Louis Joseph Xavier François Dauphin de France |  | 22 October 1781 – 4 June 1789 | Died in childhood on the very day the Estates General convened. |

| Louis XVII Francie (Nominally) King of France and Navarre |  | 27 March 1785 – 8 June 1795 | Died in childhood; žádný problém. He was never officially king, nor did he rule. His title was bestowed by his royalist supporters and acknowledged implicitly by his uncle's later adoption of the regnal name Louis XVIII rather than Louis XVII, upon the restoration of the Bourbon monarchy in 1814. |

| Sophie Hélène Béatrix |  | 9 July 1786 – 19 June 1787 | Zemřel v dětství. |

In addition to her biological children, Marie Antoinette adopted four children: "Armand" Francois-Michel Gagné (c. 1771–1792), a poor orphan adopted in 1776; Jean Amilcar (c. 1781–1793), a Senegalese otrok boy given to the queen as a present by Chevalier de Boufflers in 1787, but whom she instead had freed, baptized, adopted and placed in a pension; Ernestine Lambriquet (1778–1813), daughter of two servants at the palace, who was raised as the playmate of her daughter and whom she adopted after the death of her mother in 1788; a nakonec "Zoe" Jeanne Louise Victoire (1787-?), who was adopted in 1790 along with her two older sisters when her parents, an usher and his wife in service of the king, had died.[223]Of these, only Armand, Ernestine, and Zoe actually lived with the royal family: Jean Amilcar, along with the elder siblings of Zoe and Armand who were also formally foster children of the royal couple, simply lived at the queen's expense until her imprisonment, which proved fatal for at least Amilcar, as he was evicted from the boarding school when the fee was no longer paid, and reportedly starved to death on the street.[223] Armand and Zoe had a position which was more similar to that of Ernestine; Armand lived at court with the king and queen until he left them at the outbreak of the revolution because of his republican sympathies, and Zoe was chosen to be the playmate of the Dauphin, just as Ernestine had once been selected as the playmate of Marie-Therese, and sent away to her sisters in a convent boarding school before the Flight to Varennes in 1791.[223]

Reference

Poznámky

- ^ Jones, Daniel (2003) [1917], Peter Roach; James Hartmann; Jane Setter (eds.), Slovník výslovnosti v angličtině, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-3-12-539683-8

- ^ Fraser 2002, str. 5

- ^ Fraser 2002, s. 5–6

- ^ A b C d E F G de Decker, Michel (2005). Marie-Antoinette, les dangereuses liaisons de la reine. Paris, France: Belfond. s. 12–20. ISBN 978-2714441416.

- ^ A b de Ségur d'Armaillé, Marie Célestine Amélie (1870). Marie-Thérèse et Marie-Antoinette. Paříž, Francie: Vydání Didier Millet. pp. 34, 47.

- ^ Lever 2006, str. 10

- ^ A b Fraser 2001, pp. 22–23, 166–70

- ^ Delorme, Philippe (1999). Marie-Antoinette. Épouse de Louis XVI, mère de Louis XVII. Pygmalion Éditions. p. 13.

- ^ Lever, Évelyne (2006). 'C'état Marie-Antoinette. Paříž, Francie: Fayard. p. 14.

- ^ A b Cronin 1989, str. 45

- ^ Fraser 2002, s. 32–33

- ^ Cronin 1989, str. 46

- ^ Weber 2007[stránka potřebná ]

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 51–53

- ^ Pierre Nolhac & La Dauphine Marie Antoinette,1929, str. 46–48

- ^ Fraser 2001, s. 70–71

- ^ Nolhac 1929, pp. 55–61

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 157

- ^ Alfred et Geffroy D'Arneth & Correspondance Secrete entre Marie-Therese et le Comte de Mercy-Argenteau, vol 3 1874, pp. 80–90, 110–15

- ^ Cronin 1974, str. 61–63

- ^ Cronin 1974, str. 61

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 80–81

- ^ ALfred and Geffroy d'Arneth 1874, str. 65–75

- ^ Lever 2006

- ^ Fraser, Marie Antoinette, 2001, s. 124.

- ^ Jackes Levron & Madame du Barry 1973, pp. 75–85

- ^ Evelyne Lever & Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 124

- ^ Goncourt, Edmond de (1880). Charpentier, G. (ed.). La Du Barry. Paříž, Francie. str. 195–96.

- ^ Lever, Evelyne, Louis XV, Fayard, Paris, 1985, p. 96

- ^ Vatel, Charles (1883). Histoire de Madame du Barry: d'après ses papiers personnels et les documents d'archives. Paris, France: Hachette Livre. p. 410. ISBN 978-2013020077.

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 136–37

- ^ Arneth and Geffroy ii 1874, pp. 475–80

- ^ Castelot, André (1962). Marie-Antoinette. Paris, France: Librairie académique Perrin. pp. 107–08. ISBN 978-2262048228.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 124–27

- ^ Lever & Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 125

- ^ Cronin 1974, str. 215

- ^ Batterberry, Michael; Ruskin Batterberry, Ariane (1977). Fashion, the mirror of history. Greenwich, Connecticut: Greenwich House. p. 190. ISBN 978-0-517-38881-5.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 150–51

- ^ Erickson, Carolly (1991). To the Scaffold: The Life of Marie Antoinette. New York City: William Morrow and Company. p. 163. ISBN 978-0688073015.

- ^ Thomas, Chantal. The Wicked Queen: The Origins of the Myth of Marie Antoinette. Přeložila Julie Rose. New York: Zone Books, 2001, p. 51.

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 140–45

- ^ Arneth and Geffroy i 1874, pp. 400–10

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 129–31

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 131–32; Bonnet 1981

- ^ Fraser 2001, pp. 111–13

- ^ Howard Patricia, Gluck 1995, pp. 105–15, 240–45

- ^ Lever, Evelyne, Ludvík XVI, Fayard, Paris, 1985, pp. 289–91

- ^ Cronin 1974, pp. 158–59

- ^ Fraser, Antonia (2002). Marie Antoinette: The Journey. Nakladatelská skupina Knopf Doubleday. p. 156. ISBN 9781400033287.

- ^ „Obřízka a fimóza ve Francii v osmnáctém století“. Historie obřízky. Citováno 16. prosince 2016.

- ^ Cronin 1974, str. 159

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 160–61

- ^ Cronin 1974, str. 161

- ^ Hibbert 2002, str. 23

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 169

- ^ A b C Fraser, Antonia (2006). Marie Antoinette: The Journey. Phoenix. ISBN 9780753821404.

- ^ https://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldnews/europe/france/12096119/Marie-Antoinettes-torrid-affair-with-Swedish-count-revealed-in-decoded-letters.html

- ^ Cronin 1974, str. 162–64

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 158–71

- ^ Arneth a Geoffroy, III. 1874, s. 168–70, 180–82, 210–12

- ^ [1] Kelly Hall: „Nesprávnost, neformálnost a intimita ve Vigée Le Brun’s Marie Antoinette en Chemise“, str. 21–28. Providence College Art Journal, 2014.

- ^ Kindersley, Dorling (2012). Móda: Definitivní historie kostýmů a stylů. New York: DK Publishing. s. 146–49.

- ^ Cronin 1974, s. 127–28

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 174–79

- ^ "Marie-Antoinette | Životopis a francouzská revoluce". Encyklopedie Britannica. Citováno 3. února 2018.

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 152, 171, 194–95

- ^ A b Fraser 2001, str. 218–20

- ^ Price Munro & Preserving the Monarchy: The Comte de Vergennes, 1774–1787 1995, s. 30–35, 145–50

- ^ Meagen Elizabeth Moreland: Představení mateřství v korespondenci madame de Sévigné, Marie-Thérèse z Rakouska a Joséphine Bonaparte jejich dcerám. Kapitola I: Kontextualizace korespondence, str. 11 [vyvoláno 1. října 2016].

- ^ Arneth, Alfred (1866). Marie Antoinette; Josef II. A Leopold II (ve francouzštině a němčině). Lipsko / Paříž / Vídeň: K.F. Köhler / vyd. Jung-Treuttel / Wilhelm Braumüller. p.23 (poznámka pod čarou).

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 184–187

- ^ Cena 1995, str. 55–60

- ^ Fraser, str. 232–36

- ^ Lettres de Marie Antoinette et al., str. 42–44

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 350–53

- ^ Cronin 1974, str. 193

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 198–201

- ^ Munro Price & The Road to Versailles 2003, s. 14–15, 72

- ^ Zweig Stephan & Marie Antoinette 1938, str. 121

- ^ Farr, Evelyn, Marie Antoinette a hrabě Fersen: Nevyřčený milostný příběh

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 202

- ^ Samuel, Henry (12. ledna 2016). „Žhavá aféra Marie-Antoinette se švédským počtem odhalená v dekódovaných dopisech“. The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Hunt, Lynn. „Mnoho těl Marie Antoinetty: politická pornografie a problém ženského pohlaví ve francouzské revoluci.“ v Francouzská revoluce: nedávné debaty a nové diskuse 2. vydání, vyd. Gary Kates. New York a London: Routledge, 1998, s. 201–18.

- ^ Thomas, Chantal. Zlá královna: Počátky mýtu Marie Antoinetty. Přeložila Julie Rose. New York: Zone Books, 2001, s. 51–52.

- ^ Páka 2006, str. 158

- ^ Fraser, str. 206–08

- ^ Gutwirth, Madelyn, Soumrak bohyň: ženy a zastoupení ve francouzské revoluční éře 1992 103, 178–85, 400–05

- ^ Fraser, Antonia (2002). Marie Antoinette: The Journey. Nakladatelská skupina Knopf Doubleday. p. 207. ISBN 9781400033287.

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 208

- ^ Bombelles, Marquis de & Journal, sv. I 1977, str. 258–65

- ^ Cronin 1974, str. 204–05

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 214–15

- ^ Fraser, Antonia (2002). Marie Antoinette: The Journey. Nakladatelská skupina Knopf Doubleday. p. 217. ISBN 9781400033287.

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 216–20

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 358–60

- ^ Fraser 2001, s. 224–25

- ^ Páka 2006, str. 189

- ^ Stefan Zweig, Marie Antoinette: Portrét průměrné ženy, New York, 1933, s. 143, 244–47

- ^ Fraser 2001, s. 267–69

- ^ Ian Dunlop, Marie-Antoinette: Portrét, Londýn, 1993

- ^ Évelyne Lever, Marie-Antoinette: la dernière reine, Fayard, Paříž, 2000

- ^ Simone Bertière, Marie-Antoinette: l'insoumise„Le Livre de Poche, Paříž, 2003

- ^ Jonathan Beckman, Jak zničit královnu: Marie Antoinetta, ukradené diamanty a skandál, který otřásl francouzským trůnem, Londýn, 2014

- ^ Munro Price, Pád francouzské monarchie: Ludvík XVI., Marie Antoinetta a baron de Breteuil, Londýn, 2002

- ^ Deborah Cadbury, Ztracený francouzský král: Tragický příběh oblíbeného syna Marie-Antoinette, London, 2003, s. 22–24

- ^ Cadbury, str. 23

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 226

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 248–52

- ^ A b Fraser 2001, str. 248–50

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 246–48

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 419–20

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 250–60

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 254–55

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 254–60

- ^ Facos, str. 12.

- ^ Schama, str. 221.

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 255–58

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 257–58

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 258–59

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 260–61

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 263–65

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 2001, str. 448–53

- ^ Deník francouzské revoluce 1789–1993 a Morris Gouverneur 1939, s. 66–67

- ^ Nicolardot, Louis, Journal de Louis Seize, 1873, s. 133–38

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 274–78

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 279–82

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 462–67

- ^ iFraser 2001, str. 280–85

- ^ Dopisy vol, str. 130–40

- ^ Morris 1939, str. 130–35

- ^ Fraser 2001, s. 282–84

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 474–78

- ^ A b Fraser 2001, str. 284–89

- ^ Despaches of Earl Grower, Oscar Browning & Cambridge 1885, str. 70–75, 245–50

- ^ Journal d'émigration du prince de Condé. 1789–1795, publié par le comte de Ribes, Bibliothèque nationale de France. [2]

- ^ Castelot, Karel X.„Librairie Académique Perrin, Paříž, 1988, s. 78–79.

- ^ Despaches of Earl Grower, Oscar Browning & Cambridge, 1885, str. 70–75, 245–50

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 289

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 484–85

- ^ „dossiers d'histoire - Le Palais du Luxembourg - Sénat“. senat.fr.

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 304–08

- ^ Discours prononcé par M. Necker, Premier Ministre des Finances, à l'Assemblée Nationale, le 24. Septembre 1789.[3]

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 315

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 536–37

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 319

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 334

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 528–30

- ^ Mémoires de Mirabeau, svazek VII, s. 342.

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 524–27

- ^ 2001 & Fraser, str. 314–16

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 335

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 313

- ^ Fraser 2001, s. 321–23

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 542–52

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 336–39

- ^ Fraser 2001, s. 321–25

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 340–41

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 325–48

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 555–68

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 569–75

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 385–98

- ^ Mémoires de Madame Campan, premiérka femme de chambre de Marie-Antoinette, Le Temps retrouvé, Mercure de France, Paříž, 1988, s. 272, ISBN 2-7152-1566-5

- ^ Lettres de Marie Antoinette sv. 2 1895, str. 364–78

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 576–80

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 350, 360–71

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 353–54

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 350–52

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 357–58

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 408–09

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 599–601

- ^ 2001, str. 365–68

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 365–68

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 607–09

- ^ Castelot 1962, str. 415–16

- ^ Lever, Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 591–92

- ^ Castelot 1962, str. 418

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 371–73

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 368, 375–78

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 373–79

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 428–35

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 382–86

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 389

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 442–46

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 392

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 395–99

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 447–53

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 453–57

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 398, 408

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 411–12

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 412–14

- ^ Funck-Brentano, Frantz: Les Derniers jours de Marie-Antoinette, Flammarion, Paříž, 1933

- ^ Furneaux a 19711, str. 139–42

- ^ G. Lenotre: Poslední dny Marie Antoinetty, 1907.

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 416–20

- ^ Castelot, Marie Antoinette 1962, str. 496–500

- ^ Procès de Louis XVI, de Marie-Antoinette, de Marie-Elisabeth et de Philippe d'Orléans, Recueil de pièces authentiques, Années 1792, 1793 a 1794, De Mat, imprimeur-libraire, Bruxelles, 1821, s. 473

- ^ Castelot 1957, s. 380–85

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 429–35

- ^ Le procès de Marie-Antoinette, Ministère de la Justice, 17. října 2011 (ve francouzštině) [4]

- ^ Furneaus 1971, str. 150–54

- ^ „Poslední dopis Marie-Antoinetty“, Čaj v Trianonu, 26. května 2007

- ^ Courtois, Edme-Bonaventure; Robespierre, Maximilien de (31. ledna 2019). „Papiers inédits trouvés chez Robespierre, Saint-Just, Payan atd. Supprimés ou omis par Courtois ...“ Baudoin - prostřednictvím Knih Google.

- ^ Chevrier, M. -R; Alexandre, J .; Laux, Christian; Godechot, Jacques; Ducoudray, Emile (1983). „Documents intéressant E.B. Courtois. In: Annales historiques de la Révolution française, 55e Année, č. 254 (Octobre – Décembre 1983), s. 624–28“. Annales Historiques de la Révolution Française. 55 (254): 624–35. JSTOR 41915129.

- ^ Furneaus 1971, str. 155–56

- ^ Castelot 1957, str. 550–58

- ^ Lever & Marie Antoinette 1991, str. 660

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 440

- ^ The Times 23. října 1793, Časy.

- ^ "Slavná poslední slova". 23. května 2012.

- ^ „Marie Tussaud“. encyclopedia.com. Citováno 28. března 2016.

- ^ Ragon, Michel, L'espace de la mort, Essai sur l'architecture, la décoration et l'urbanisme funéraires, Michel Albin, Paříž, 1981, ISBN 978-2-226-22871-0 [5]

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. 411, 447

- ^ Hunt, Lynn (1998). „Mnoho těl Marie Antoinetty: politická pornografie a problém ženského pohlaví ve francouzské revoluci“. V Kates, Gary (ed.). Francouzská revoluce: nedávné debaty a nové diskuse (2. vyd.). Londýn, Anglie: Routledge. str.201–18. ISBN 978-0415358330.

- ^ Kaiser, Thomas (podzim 2003). „Od rakouského výboru po zahraniční spiknutí: Marie-Antoinette, Austrophobia and the Terror“. Francouzské historické studie. Durham, Severní Karolína: Duke University Press. 26 (4): 579–617. doi:10.1215/00161071-26-4-579. S2CID 154852467.

- ^ Thomas, Chantal (2001). Zlá královna: Počátky mýtu Marie Antoinetty. Přeložila Julie Rose. New York City: Zone Books. p. 149. ISBN 0942299396.

- ^ Jenner, Victoria (12. listopadu 2019). „Oslava Marie-Antoinette k jejím narozeninám“. Waddesdon Manor. Citováno 18. listopadu 2019.

- ^ Jefferson, Thomas (2012). Autobiografie Thomase Jeffersona. Mineola, New York: Courier Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0486137902. Citováno 29. března 2013.

Někdy jsem věřil, že kdyby neexistovala královna, nebyla by žádná revoluce.

- ^ Fraser 2001, str. xviii, 160; Páka 2006, str. 63–65; Lanser 2003, str. 273–90

- ^ Johnson 1990, str. 17

- ^ Sturtevant, str. 14, 72.

- ^ luizhadsen Paulnewton (24. září 2016), Marie Antoinetta 2006 Celý film, vyvoláno 1. prosince 2016

- ^ Hartmann, Christian (15. listopadu 2020). „Hedvábná bota Marie Antoinette jde do prodeje ve Versailles“. Reuters. Citováno 15. listopadu 2020.

- ^ A b C Philippe Huisman, Marguerite Jallut: Marie Antoinette, Stephens, 1971

Bibliografie

- Bonnet, Marie-Jo (1981). Un choix sans équivoque: recherches historiques sur les relations amoureuses entre les femmes, XVIe – XXe siècle (francouzsky). Paříž: Denoël. OCLC 163483785.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Castelot, André (1957). Královna Francie: biografie Marie Antoinette. trans. Denise Folliot. New York: Harper & Brothers. OCLC 301479745.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Cronin, Vincent (1989). Louis a Antoinette. London: The Harvill Press. ISBN 978-0-00-272021-2.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Dams, Bernd H .; Zega, Andrew (1995). La folie de bâtir: pavillons d'agrément et folies sous l'Ancien Régime. trans. Alexia Walker. Flammarion. ISBN 978-2-08-201858-6.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Facos, Michelle (2011). Úvod do umění devatenáctého století. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-84071-5. Citováno 1. září 2011.

- Fraser, Antonia (2001). Marie Antoinette (1. vyd.). New York: N.A. Talese / Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-385-48948-5.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Fraser, Antonia (2002). Marie Antoinette: The Journey (2. vyd.). Garden City: Anchor Books. ISBN 978-0-385-48949-2.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Hermann, Eleanor (2006). Sex s královnou. Harper / Morrow. ISBN 978-0-06-084673-2.

- Hibbert, Christopher (2002). Dny francouzské revoluce. Harperova trvalka. ISBN 978-0-688-16978-7.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Johnson, Paul (1990). Intelektuálové. New York: Harper & Row. ISBN 978-0-06-091657-2.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Lanser, Susan S. (2003). "Jíst dort: (Ab) použití Marie-Antoinette". V Goodman, Dena (ed.). Marie-Antoinette: Spisy na těle královny. Psychologie Press. ISBN 978-0-415-93395-7.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Páka, Évelyne (2006). Marie Antoinette: Poslední francouzská královna. London: Portrait. ISBN 978-0-7499-5084-2.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Schama, Simon (1989). Občané: Kronika francouzské revoluce. New York: Vintage. ISBN 978-0-679-72610-4.

- Seulliet, Philippe (červenec 2008). „Labutí píseň: Hudební pavilon poslední francouzské královny“. Svět interiérů (7).CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Sturtevant, Lynne (2011). Průvodce po historické Mariettě v Ohiu. Historie tisku. ISBN 978-1-60949-276-2. Citováno 1. září 2011.

- Weber, Caroline (2007). Queen of Fashion: What Marie Antoinette Wear to the Revolution. Pikador. ISBN 978-0-312-42734-4.CS1 maint: ref = harv (odkaz)

- Wollstonecraft, Mary (1795). Historický a morální pohled na vznik a pokrok francouzské revoluce a dopad, který přinesla v Evropě. St. Paul's.

- Farr, Evelyn (2009). Nevyřčený milostný příběh: Marie Antoinette a hrabě Fersen. Nakladatelé Peter Owen.

Další čtení

- Bashor, Will (2013). Marie Antoinette's Head: The Royal Hairdresser, the Queen, and the Revolution. Lyons Press. p. 320. ISBN 978-0762791538.