Divné příběhy - Weird Tales

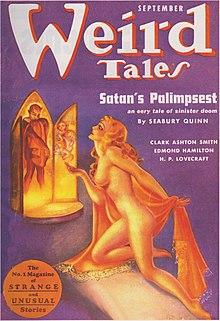

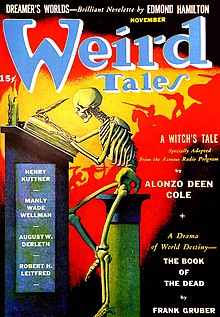

Divné příběhy je Američan fantazie a hororová fikce zásobník buničiny založené J. C. Hennebergerem a J. M. Lansingerem koncem roku 1922. První vydání z března 1923 se objevilo na novinových stáncích 18. února.[2] První editor, Edwin Baird, tištěná raná práce od H. P. Lovecraft, Seabury Quinn, a Clark Ashton Smith, z nichž všichni by se stali populárními spisovateli, ale do roku se časopis dostal do finančních potíží. Henneberger prodal svůj podíl ve vydavatelství Rural Publishing Corporation společnosti Lansinger a refinancoval Divné příběhy, s Farnsworth Wright jako nový editor. První číslo pod kontrolou Wrighta bylo vydáno v listopadu 1924. Časopis byl pod Wrightem úspěšnější a navzdory občasným finančním neúspěchům prosperoval v příštích patnácti letech. Pod Wrightovou kontrolou časopis splnil svůj podtitul „The Unique Magazine“ a publikoval celou řadu neobvyklých fikcí.

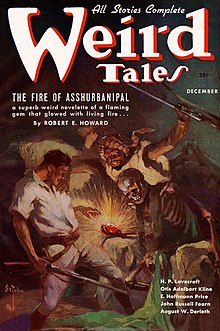

Lovecraft Cthulhu mythos příběhy se poprvé objevily v Divné příběhy, začínání s "Volání Cthulhu „v roce 1928. Byly dobře přijaty a skupina spisovatelů spojených s Lovecraftem napsala další příběhy odehrávající se ve stejném prostředí. Robert E. Howard byl pravidelným přispěvatelem a několik jeho publikoval Barbar Conan příběhy v časopise a série příběhů Seabury Quinna o Jules de Grandin Detektiv, který se specializoval na případy nadpřirozených věcí, byl mezi čtenáři velmi oblíbený. Včetně dalších oblíbených autorů Nictzin Dyalhis, E. Hoffmann Cena, Robert Bloch, a H. Warner Munn. Wright některé publikoval sci-fi, spolu s fantazií a hrůzou, částečně proto, že kdy Divné příběhy byl spuštěn neexistovaly žádné časopisy specializující se na science fiction, ale v této politice pokračoval i po zavedení časopisů jako např Úžasné příběhy v roce 1926. Edmond Hamilton napsal hodně sci-fi pro Divné příběhy, i když po několika letech použil časopis pro své fantastickější příběhy a předložil své vesmírné opery někde jinde.

V roce 1938 byl časopis prodán Williamovi Delaneyovi, vydavateli časopisu Povídky, a do dvou let byl Wright, který byl nemocný, nahrazen Dorothy McIlwraith jako editor. Ačkoli někteří úspěšní noví autoři a umělci, jako např Ray Bradbury a Hannes Bok Kritici časopis nadále považují za časopis, který podle časopisu McIlwraith upadl od svého rozkvětu ve 30. letech. Divné příběhy přestal vycházet v roce 1954, ale od té doby byly učiněny četné pokusy o opětovné spuštění časopisu, počínaje rokem 1973. Nejdéle trvající verze začala v roce 1988 a běžela s občasnou přestávkou více než 20 let pod řadou vydavatelů. V polovině 90. let byl název změněn na Worlds of Fantasy & Horror kvůli problémům s licencí, přičemž původní titul se vrátil v roce 1998.

Časopis je historiky fantasy a science fiction považován za legendu v oboru, s Robert Weinberg, autor historie časopisu, který jej považuje za „nejdůležitější a nejvlivnější ze všech fantasy časopisů“.[3] Weinbergův kolega historik, Mike Ashley, je opatrnější, popisuje to jako „sekunda po Neznámý význam a vliv ",[4] a dodává, že „někde v rezervoáru představivosti všech amerických (a mnoha jiných než amerických) autorů žánrů fantasy a hororů je součástí ducha Divné příběhy".[5]

Pozadí

Na konci 19. století populární časopisy obvykle netiskly beletrii s vyloučením jiného obsahu; zahrnovaly by také články z oblasti beletrie a poezii. V říjnu 1896 se Frank A. Munsey společnosti Argosy časopis jako první přešel na tisk pouze beletrie a v prosinci téhož roku se to změnilo na používání levného papíru z dřevoviny. Toto je nyní historiky časopisů považováno za začátek zásobník buničiny éra. Po celá léta byly časopisy o vláknině úspěšné, aniž by omezily svůj fikční obsah na jakýkoli konkrétní žánr, ale v roce 1906 zahájil Munsey Časopis Railroad Man's, první titul zaměřený na konkrétní místo. Následovaly další tituly, které se specializovaly na konkrétní žánry beletrie, počínaje rokem 1915 s Časopis Detective Story, s Western Story Magazine následující v roce 1919.[6] Divná fikce, sci-fi, a fantazie všechny se často objevovaly v buničinách dne, ale na počátku 20. let 20. století stále neexistoval jediný časopis zaměřený na žádný z těchto žánrů, ačkoli Kniha vzrušení, která byla zahájena v roce 1919 Street & Smith s úmyslem tisknout „jiné“ nebo neobvyklé příběhy bylo téměř zmeškané.[6][7]

V roce 1922 J. C. Henneberger, vydavatel Vysokoškolský humor a Časopis zábavy, založil společnost Rural Publishing Corporation v Chicagu ve spolupráci se svým bývalým bratrem z bratrství J. M. Lansingerem.[8] Jejich první podnik byl Detektivní příběhy, časopis o buničině, který se objevil dvakrát měsíčně, počínaje vydáním 1. října 1922. Zpočátku to bylo neúspěšné a v rámci plánu refinancování se Henneberger rozhodl vydat další časopis, který by mu umožnil rozdělit část svých nákladů mezi tyto dva tituly. Henneberger už dlouho obdivoval Edgar Allan Poe, a tak vytvořil beletristický časopis, který by se zaměřil na horor, a nazval jej Divné příběhy.[9][10]

Historie publikace

Rural Publishing Corporation

| Jan | Února | Mar | Dubna | Smět | Červen | Jul | Srpen | Září | Října | listopad | Prosinec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1923 | 1/1 | 1/2 | 1/3 | 1/4 | 2/1 | 2/2 | 2/3 | 2/4 | ||||

| 1924 | 3/1 | 3/2 | 3/3 | 3/4 | 4/2 | 4/3 | 4/4 | |||||

| 1925 | 5/1 | 5/2 | 5/3 | 5/4 | 5/5 | 5/6 | 6/1 | 6/2 | 6/3 | 6/4 | 6/5 | 6/6 |

| 1926 | 7/1 | 7/2 | 7/3 | 7/4 | 7/5 | 7/6 | 8/1 | 8/2 | 8/3 | 8/4 | 8/5 | 8/6 |

| 1927 | 9/1 | 9/2 | 9/3 | 9/4 | 9/5 | 9/6 | 10/1 | 10/2 | 10/3 | 10/4 | 10/5 | 10/6 |

| 1928 | 11/1 | 11/2 | 11/3 | 11/4 | 11/5 | 11/6 | 12/1 | 12/2 | 12/3 | 12/4 | 12/5 | 12/6 |

| 1929 | 13/1 | 13/2 | 13/3 | 13/4 | 13/5 | 13/6 | 14/1 | 14/2 | 14/3 | 14/4 | 14/5 | 14/6 |

| 1930 | 15/1 | 15/2 | 15/3 | 15/4 | 15/5 | 15/6 | 16/1 | 16/2 | 16/3 | 16/4 | 16/5 | 16/6 |

| 1931 | 17/1 | 17/2 | 17/3 | 17/4 | 18/1 | 18/2 | 18/3 | 18/4 | 18/5 | |||

| 1932 | 19/1 | 19/2 | 19/3 | 19/4 | 19/5 | 19/6 | 20/1 | 20/2 | 20/3 | 20/4 | 20/5 | 20/6 |

| 1933 | 21/1 | 21/2 | 21/3 | 21/4 | 21/5 | 21/6 | 22/1 | 22/2 | 22/3 | 22/4 | 22/5 | 22/6 |

| 1934 | 23/1 | 23/2 | 23/3 | 23/4 | 23/5 | 23/6 | 24/1 | 24/2 | 24/3 | 24/4 | 24/5 | 24/6 |

| 1935 | 25/1 | 25/2 | 25/3 | 25/4 | 25/5 | 25/6 | 26/1 | 26/2 | 26/3 | 26/4 | 26/5 | 26/6 |

| 1936 | 27/1 | 27/2 | 27/3 | 27/4 | 27/5 | 27/6 | 28/1 | 28/2 | 28/3 | 28/4 | 28/5 | |

| 1937 | 29/1 | 29/2 | 29/3 | 29/4 | 29/5 | 29/6 | 30/1 | 30/2 | 30/3 | 30/4 | 30/5 | 30/6 |

| 1938 | 31/1 | 31/2 | 31/3 | 31/4 | 31/5 | 31/6 | 32/1 | 32/2 | 32/3 | 32/4 | 32/5 | 32/6 |

| 1939 | 33/1 | 33/2 | 33/3 | 33/4 | 33/5 | 34/1 | 34/2 | 34/3 | 34/4 | 34/5 | 34/6 | |

| 1940 | 35/1 | 35/2 | 35/3 | 35/4 | 35/5 | 35/6 | ||||||

| Problémy Divné příběhy od roku 1923 do roku 1940, s uvedením čísla svazku / čísla. Editoři byli Edwin Baird (žlutý), Farnsworth Wright (modrý) a Dorothy McIlwraith (zelený). Nebyl žádný problém s číslem 4/1.[11] | ||||||||||||

Henneberger si vybral Edwin Baird, redaktor Detektivní příběhy, upravovat Divné příběhy; Farnsworth Wright byl první čtenář, a Otis Adelbert Kline také pracoval na časopise a pomáhal Bairdovi. Sazby plateb byly nízké, obvykle mezi čtvrtinou a půl centu za slovo; rozpočet se u nejpopulárnějších autorů zvýšil na jeden cent za slovo.[10] Prodeje byly zpočátku špatné a společnost Henneberger se brzy rozhodla změnit formát ze standardní velikosti buničiny na velká buničina, aby byl časopis lépe viditelný. To mělo malý dlouhodobý dopad na prodej, ačkoli první vydání v nové velikosti z května 1923 bylo jediné, které se v prvním roce úplně vyprodalo - pravděpodobně proto, že obsahovalo první díl populárního seriálu, Měsíční terorautor: A.G. Birch.[12][13]

Časopis ztratil pod vydavatelstvím Baird značné množství peněz: po třinácti vydáních celkový dluh přesáhl 40 000 $.[14][poznámky 1] Mezitím, Detektivní příběhy byl retitled Skutečné detektivní příběhy a stejně tak dosahoval zisku Vysokoškolský humor. Henneberger se rozhodl prodat oba časopisy Lansingerovi a investovat do nich peníze Divné příběhy.[12][16] To neřešilo dluhy ve výši 40 000 USD, z nichž většina byla dlužena tiskárně časopisu. Tiskařskou společnost vlastnil B. Cornelius, který souhlasil s Hennebergerovým návrhem, aby byl dluh přeměněn na většinový podíl v nové společnosti Popular Fiction Publishing. To nevylučovalo všechny dluhy časopisu, ale znamenalo to Divné příběhy mohl pokračovat v publikování a možná se vrátil k ziskovosti. Cornelius souhlasil, že pokud by se časopis stal dostatečně ziskovým, aby mu splatil dlužných 40 000 $, vzdal by se svých akcií ve společnosti. Cornelius se stal pokladníkem společnosti; obchodním manažerem byl William (Bill) Sprenger, který pracoval pro Rural Publishing. Henneberger doufal, že dluh nakonec refinancuje pomocí další tiskárny, společnosti Hall Printing Company, kterou vlastní Robert Eastman.[12]

Baird zůstal u Lansingera, takže Henneberger napsal H. P. Lovecraft, který prodal několik příběhů Divné příběhy, aby zjistil, zda by měl zájem tuto práci převzít. Henneberger nabídl desetitýdenní zálohu, ale stanovil podmínku, aby se Lovecraft přestěhoval do Chicaga, kde mělo sídlo časopis. Lovecraft popsal Hennebergerovy plány v dopise Frank Belknap Long jako „zbrusu nový časopis pro oblast chvění Poe-Machenů“. Lovecraft nechtěl opustit New York, kam se nedávno přestěhoval se svou novou nevěstou; jeho nechuť k chladnému počasí byla dalším odstrašujícím prostředkem.[12][17][18][poznámky 2] Strávil několik měsíců zvažováním nabídky v polovině roku 1924, aniž by učinil konečné rozhodnutí, přičemž Henneberger ho navštívil v Brooklynu více než jednou, ale nakonec buď odmítl, nebo se Henneberger jednoduše vzdal. Do konce roku byl Wright najat jako nový redaktor časopisu Divné příběhy. Posledním číslem pod Bairdovým jménem bylo kombinované číslo květen / červen / červenec se 192 stránkami - mnohem silnější časopis než ta předchozí. To bylo sestaveno Wrightem a Kline, spíše než Baird.[12]

Populární vydávání beletrie

Henneberger dal Wrightovi plnou kontrolu Divné příběhy, a nezapojil se do výběru příběhu. Asi v roce 1921 Wright začal trpět Parkinsonova choroba a během jeho redakční činnosti se příznaky postupně zhoršovaly. Na konci 20. let nemohl podepsat své jméno a koncem 30. let mu pomohl Bill Sprenger dostat se do práce a zpět domů.[12] První vydání s Wrightem jako redaktorem bylo datováno listopadem 1924 a časopis okamžitě obnovil pravidelný měsíční plán, přičemž formát se opět změnil na buničinu.[11] Mzda byla zpočátku nízká, s limitem půl centu za slovo až do roku 1926, kdy byla nejvyšší sazba zvýšena na jeden cent za slovo. Některé dluhy vydavatelství Popular Fiction Publishing byly v průběhu času splaceny a nejvyšší platová sazba se nakonec zvýšila na jeden a půl centu za slovo.[poznámky 3] Cena obálky časopisu byla na tu dobu vysoká. Robert Bloch připomněl, že „na konci dvacátých a třicátých let tohoto století ... v době, kdy se většina buničinových periodik prodávala za desetník, byla jejich cena čtvrtinová“.[23] Ačkoli společnost Popular Fiction Publishing nadále sídlila v Chicagu, redakce byly na chvíli na dvou samostatných adresách v Indianapolis, ale do Chicaga se přestěhovaly koncem roku 1926. Po krátké době North Broadway, kancelář se přesunula na 840 North Michigan Avenue, kde by zůstal až do roku 1938.[24]

V roce 1927 vydalo Popular Fiction Publishing Birch's Měsíční teror, jeden z Divné příběhy' více populárních seriálů, jako kniha v pevné vazbě, včetně tří dalších příběhů z prvního ročníku časopisu. Jeden z příběhů, „Dobrodružství ve čtvrté dimenzi“, byl od samotného Wrighta. Kniha se prodávala špatně a zůstala v nabídce na stránkách Divné příběhy, za snížené ceny, na dvacet let.[24][25] Bylo to v jednom okamžiku poskytnuto jako bonus čtenářům, kteří se přihlásili k odběru.[26] V roce 1930 Cornelius spustil doprovodný časopis, Orientální příběhy, ale časopis nebyl úspěšný, i když dokázal vydržet déle než tři roky, než se Cornelius vzdal.[24][27] Další finanční rána nastala koncem roku 1930, kdy bankovní selhání zmrazilo většinu hotovosti časopisu. Henneberger změnil plán na dvouměsíčník, počínaje číslem únor / březen 1931; o šest měsíců později, s vydáním v srpnu 1931, se měsíční plán vrátil.[28] O dva roky později Divné příběhy„banka měla stále finanční problémy a platby autorům se podstatně zpožďovaly.[29]

The Deprese zasáhla také Hall Printing Company, v kterou Henneberger doufal, že převezme dluh od Cornelia; Robert Eastman, majitel společnosti Hall, v jednom okamžiku nebyl schopen splnit výplatní listinu. Eastman zemřel v roce 1934 a spolu s ním šly Hennebergerovy plány na získání kontroly nad Divné příběhy.[24] Časopis inzeroval v raných sci-fi buničinách, obvykle zdůrazňoval jeden z více sci-fi příběhů. Inzerovaný příběh byl často Edmond Hamilton, který byl populární v časopisech sf. Wright také prodával vázané knihy od některých svých populárnějších autorů, jako je Kline, na stránkách Divné příběhy.[30] Ačkoli časopis nikdy nebyl příliš výnosný, Wright byl dobře placen. Robert Weinberg, autor historie Divné příběhy, zaznamenává pověst, že Wright nebyl za většinu své práce v časopise placen, ale podle E. Hoffmann Cena, blízký Wrightův přítel, který pro něj občas četl rukopisy, Divné příběhy platil Wrightovi v roce 1927 přibližně 600 $ měsíčně.[24]

Delaney

| Jan | Února | Mar | Dubna | Smět | Červen | Jul | Srpen | Září | Října | listopad | Prosinec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1941 | 35/7 | 35/8 | 35/9 | 35/10 | 36/1 | 36/2 | ||||||

| 1942 | 36/3 | 36/4 | 36/5 | 36/6 | 36/7 | 36/8 | ||||||

| 1943 | 36/9 | 36/10 | 36/11 | 36/12 | 37/1 | 37/2 | ||||||

| 1944 | 37/3 | 37/4 | 37/5 | 37/6 | 38/1 | 38/2 | ||||||

| 1945 | 38/3 | 38/4 | 38/5 | 38/6 | 39/1 | 39/2 | ||||||

| 1946 | 39/3 | 39/4 | 39/5 | 39/6 | 39/7 | 39/8 | ||||||

| 1947 | 39/9 | 39/10 | 39/11 | 39/11 | 39/12 | 40/1 | ||||||

| 1948 | 40/2 | 40/3 | 40/4 | 40/5 | 40/6 | 41/1 | ||||||

| 1949 | 41/2 | 41/3 | 41/4 | 41/5 | 41/6 | 42/1 | ||||||

| 1950 | 42/2 | 42/3 | 42/4 | 42/5 | 42/6 | 43/1 | ||||||

| 1951 | 43/2 | 43/3 | 43/4 | 43/5 | 43/6 | 44/1 | ||||||

| 1952 | 44/2 | 44/3 | 44/4 | 44/5 | 44/6 | 44/7 | ||||||

| 1953 | 44/8 | 45/1 | 45/2 | 45/3 | 45/4 | 45/5 | ||||||

| 1954 | 45/6 | 46/1 | 46/2 | 46/3 | 46/4 | |||||||

| Problémy Divné příběhy z let 1941-54, číslo svazku / čísla vydání. (1) Primární editor byl Dorothy McIlwraith. Pomocný redaktor Lamont Buchanan (červený) měl primární editační povinnosti od o létě 1945 díky jeho rezignaci v roce 1949. Posledním problémem, který ho uvedl na seznamu v tiráži, je Září 1949. Otázka označující přesný začátek jeho redakční činnosti není v současné době známa.[31] (2) Zjevná chyba při duplikování svazku 39/11 je ve skutečnosti správná.[11] | ||||||||||||

Cornelius odešel do důchodu v roce 1938 a společnost Popular Fiction Publishing byla prodána Williamovi J. Delaneyovi, který byl vydavatelem Povídky, úspěšný obecný časopis o buničině se sídlem v New Yorku. Sprenger a Wright oba dostali podíl na akciích od Cornelia; Sprenger ve společnosti nezůstal, ale Wright se přestěhoval do New Yorku a zůstal jako redaktor.[28][30] Hennebergerův podíl v nakladatelství Popular Fiction Publishing byl převeden na malý zájem o novou společnost Weird Tales, Inc., dceřinou společnost Delaney's Short Stories, Inc.[11][30] Dorothy McIlwraith, redaktorka Povídky, se stal Wrightovým asistentem a v příštích dvou letech se Delaney pokusila zvýšit zisky úpravou počtu a ceny stránky. Zvýšení ze 144 stran na 160 stran počínaje vydáním v únoru 1939, spolu s použitím levnějšího (a tedy silnějšího) papíru způsobilo, že byl časopis tlustší, ale to se nepodařilo zvýšit prodej. V září 1939 počet stránek klesl na 128 a cena byla snížena z 25 centů na 15 centů. Od ledna 1940 byla frekvence snížena na dvouměsíčník, což byla změna, která zůstala v platnosti až do konce běhu časopisu o čtrnáct let později.[28][30] Žádná z těchto změn neměla zamýšlený účinek a tržby se nadále zhoršovaly.[30] V březnu 1940 Wright odešel a byl nahrazen McIlwraithem jako redaktorem; historie časopisu se liší v tom, zda byl propuštěn z důvodu špatného prodeje, nebo skončil kvůli svému zdraví - teď už trpěl Parkinsonovou chorobou tak vážně, že měl potíže s chůzí bez pomoci.[28][30][32][33][poznámky 4] Wright poté podstoupil operaci ke zmírnění bolesti, kterou trpěl, ale nikdy se úplně nezotavil. Zemřel v červnu téhož roku.[12]

První vydání McIlwraitha bylo datováno dubnem 1940. Od roku 1945[34] přes 1949,[35] pomáhal jí Lamont Buchanan, který pro ni pracoval jako pomocný redaktor a umělecký redaktor pro oba Divné příběhy a Povídky. August Derleth také poskytoval pomoc a radu, ačkoli s časopisem neměl žádné formální spojení. Většina rozpočtu McIlwraitha šla do Povídky, protože to byl úspěšnější časopis;[30][33] sazba platby za beletrii v Divné příběhy do roku 1953 to byl jeden cent za slovo, což je výrazně pod nejvyšší úrovní ostatních vtedajších sci-fi a fantasy časopisů.[36] Problémy způsobil také válečný nedostatek a počet stránek se snížil, nejprve na 112 stránek v roce 1943 a poté na 96 stránek v následujícím roce.[30][33]

Cena byla zvýšena na 20 centů v roce 1947 a znovu na 25 centů v roce 1949, ale nejen to Divné příběhy to trpělo - celý průmysl buničiny upadal. Delaney přepnul formát na strávit s vydáním ze září 1953, ale neměla být žádná odklad. V roce 1954 Divné příběhy a Povídky zastavil publikaci; v obou případech bylo poslední vydání vydáno v září 1954.[30][37] Pro Divné příběhy, číslo ze září 1954 bylo jeho 279. číslem.[38]

70. a začátek 80. let

| Jaro | Léto | Podzim | Zima | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1973 | 47/1 | 47/2 | 47/3 | |||||||||

| 1974 | 47/4 | |||||||||||

| 1981 | 1 & 2 | 3 | ||||||||||

| 1983 | 4 | |||||||||||

| 1984 | 49/1 | |||||||||||

| 1985 | 49/2 | |||||||||||

| 1988 | 50/1 | 50/2 | 50/3 | 50/4 | ||||||||

| 1989 | 51/1 | 51/2 | ||||||||||

| 1990 | 51/3 | 51/4 | 52/1 | 52/2 | ||||||||

| 1991 | 52/3 | 52/4 | 53/1 | 53/2 | ||||||||

| 1992 | 53/3 | 53/4 | ||||||||||

| 1993 | 53/3 | 53/3 | ||||||||||

| 1994 | 53/3 | 1/1 | ||||||||||

| 1995 | 1/2 | |||||||||||

| 1996 | 1/3 | 1/4 | ||||||||||

| 1998 | 55/1 | 55/2 | ||||||||||

| 1999 | 55/3 | 55/4 | 56/1 | 56/2 | ||||||||

| 2000 | 56/3 | 56/4 | 57/1 | 57/2 | ||||||||

| 2001 | 57/3 | 57/4 | 58/1 | 58/2 | ||||||||

| 2002 | 58/3 | 58/4 | 59/1 | 59/2 | ||||||||

| Problémy Divné příběhy od roku 1988 do roku 2002, ukazující objem a čísla vydání. Všimněte si, že čtyři čísla začínající létem 1994 měla název Worlds of Fantasy & Horror. Pět zimních čísel bylo datováno dvěma roky: 1988/1989, 1992/1993; 1996/1997, 2001/2002 a 2002/2003. Redaktoři byli Moskowitz (šedá), Carter (fialová), Ackerman & Lamont (jasně růžová), Garb (zelená), Schweitzer, Scithers a Betancourt (oranžová); Schweitzer (tmavě růžová); a Scithers and Schweitzer (žlutá).[39] | ||||||||||||

V polovině 50. let Leo Margulies, známá postava ve světě vydávání časopisů, založila novou společnost Renown Publications s plány vydat několik titulů. Získal práva k oběma Divné příběhy a Povídkya doufali, že oba časopisy přivedou zpět. Opustil plán restartu Divné příběhy v roce 1962, poté, co byl poučen dotisky z původního časopisu Sam Moskowitz že v té době existoval malý trh pro podivné a hororové fikce.[40][poznámky 5] Místo toho Margulies těžil Divné příběhy backfile pro čtyři antologie, které se objevily na počátku 60. let: Neočekávaný, Ghoul-Keepers, Divné příběhy, a Worlds of Weird.[41] Posledně jmenované byly duchovně upraveny Moskowitzem, který Marguliesovi navrhl, že když nastal čas na opětovné spuštění časopisu, měl by obsahovat dotisky z obskurních zdrojů, které Moskowitz našel, spíše než jen příběhy přetištěné z první inkarnace Divné příběhy.[41][43] Tyto příběhy by byly pro většinu čtenářů úplně nové a ušetřené peníze by mohly být použity na příležitostný nový příběh.[41]

Nová verze Divné příběhy se konečně objevil v publikaci Renown Publications, v dubnu 1973, editoval Moskowitz. Měl slabou distribuci a prodeje byly příliš nízké na udržitelnost; podle Moskowitze byl průměrný prodej 18 000 výtisků na jedno vydání, což je výrazně méně než 23 000 výtisků, které by časopis potřeboval k přežití. Čtvrté číslo z léta 1974 bylo poslední, protože Margulies zavřel všechny své časopisy kromě Tajemný časopis Mike Shayne, který jako jediný dosahoval zisku. Mike Ashley, historik časopisu sci-fi, zaznamenává, že Moskowitz nebyl v žádném případě ochotný pokračovat, protože ho štvalo podrobné zapojení Margulies do každodenních redakčních úkolů, jako je editace rukopisů a psaní úvodů.[41]

Margulies zemřel následující rok a jeho vdova Cylvia Margulies se rozhodla prodat práva k titulu. Forrest Ackerman, fanoušek a redaktor sci-fi, byla jednou ze zúčastněných stran, ale místo toho se rozhodla prodat Victorovi Dricksovi a Robertu Weinbergovi.[44] Weinberg zase získal licenci na titul Lin Carter, kteří mají zájem o vydavatele, Knihy Zebra, v projektu. Výsledkem byla série čtyři brožované antologie, editoval Lin Carter, objevuje se v letech 1981 až 1983;[45] původně se plánovalo, že budou čtvrtletní, ale ve skutečnosti se první dva objevily v prosinci 1980 a oba byly datovány na jaře 1981. Další byly datovány na podzim 1981;[46] Carterova práva na titul byla ukončena Weinbergem v roce 1982 z důvodu neplacení, ale čtvrté vydání již bylo v pracích a nakonec se objevilo s datem léta 1983.[47]

V roce 1982 Sheldon Jaffery a Roy Torgeson setkal se s Weinbergem, aby navrhli převzetí jako držitelé licence, ale Weinberg se rozhodl nabídku nepokračovat. Následující rok Brian Forbes oslovil Weinberga s další nabídkou. Forbesova společnost, Bellerophon Network, byla otiskem losangeleské společnosti The Wizard. Ashley uvádí, že Weinberg byl schopen kontaktovat Forbes pouze telefonicky, ai to nebylo vždy spolehlivé, takže jednání byla pomalá. Redakčním ředitelem Forbesu byl Gordon Garb a redaktorem beletrie Gil Lamont; Forrest Ackerman také pomáhal, hlavně získáním materiálu, který měl zahrnout. Mezi různými účastníky projektu došlo k velkému zmatku:[48] podle Místo, obchodní sci-fi časopis, "Ackerman říká, že nebyl v kontaktu s vydavatelem Forbes, neví, co se stane s materiálem, který sestavil, a je stejně temný jako všichni ostatní. Lamont říká, že stále znovu vyjednává jeho smlouvy a není si jistý, kde stojí “.[49] Původní plán spočíval v tom, že první vydání se objeví v srpnu 1984, datováno červenec / srpen, ale než se objevilo, bylo přijato rozhodnutí změnit obsah a na konci roku se konečně objevil nový, úplně resetovaný problém, datovaný Fall 1984. I s tímto zpožděním ještě nebyla s Weinbergem dosažena konečná dohoda o udělování licencí. Bylo vytištěno pouze 12 500 kopií; ty byly zaslány dvěma distributorům, kteří se dostali do bankrotu. Výsledkem bylo, že se prodalo jen několik kopií a distributoři Forbes nezaplatili. Navzdory finančnímu neúspěchu se Forbes pokusil pokračovat a nakonec se objevila druhá otázka. Jeho titulní datum bylo zima 1985, ale to bylo vydáno až v červnu 1986. Bylo vytištěno několik kopií; zprávy se pohybují celkem mezi 1 500 a 2 300. Mark Monsolo byl redaktorem beletrie, ale Garb pokračoval jako redaktor; Lamont už s časopisem nebyl v kontaktu.[48]

Terminus a jeho nástupci

| Jaro | Léto | Podzim | Zima | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Jan | Února | Mar | Dubna | Smět | Červen | Jul | Srpen | Září | Října | listopad | Prosinec | |

| 2003 | 59/3 | 59/4 | 60/1 | |||||||||

| 2004 | 60/2 | 60/3 | 60/4 | |||||||||

| 2005 | 337 | |||||||||||

| 2006 | 338 | 339 | 340 | 341 | 342 | |||||||

| 2007 | 343 | 344 | 345 | 346 | 347 | |||||||

| 2008 | 348 | 349 | 350 | 351 | 352 | |||||||

| Problémy Divné příběhy od roku 2003 do roku 2008, ukazující objem a čísla vydání. Většina čísel byla pojmenována buď s měsícem, nebo se dvěma měsíci (např. „Březen / duben 2004“). Jedno číslo, jaro 2003, bylo nazváno sezónou. Redaktoři byli Scithers a Schweitzer (žlutá); Scithers, Schweitzer a Betancourt (oranžová); Segal (modrý); a Vandermeer (šedá).[39] | ||||||||||||

Divné příběhy byl trvaleji oživen na konci 80. let 20. století George H. Scithers, John Gregory Betancourt a Darrell Schweitzer, která založila společnost Terminus Publishing se sídlem ve Filadelfii a poskytla licenci na práva od Weinberga. Spíše než se soustředit na distribuci novinového stánku, která byla nákladná a v 80. letech se stala méně efektivní, plánovali vybudovat základnu přímých předplatitelů a distribuovat časopis k prodeji prostřednictvím specializovaných obchodů.[50] První vydání mělo krycí datum na jaře 1988, ale bylo vyrobeno dostatečně brzy na to, aby bylo k dispozici v roce 1987 Světová fantasy úmluva v Nashville, Tennessee.[50][51] Velikost byla stejná jako původní verze buničiny, i když byla vytištěna na lepším papíru. K dispozici byly také omezené verze vázaných verzí každého čísla podepsané přispěvateli. Speciální World Fantasy Award Divné příběhy obdržené v roce 1992 ukázalo, že časopis byl úspěšný z hlediska kvality, ale tržby nebyly dostatečné k pokrytí nákladů. Kvůli úspoře peněz byl formát změněn na větší plochý formát, počínaje číslem zima 1992/1993, ale časopis zůstal ve finančních potížích, přičemž problémy se v příštích několika letech staly nepravidelnými. Číslo léta 1993 bylo posledním vydáním vázané knihy; to bylo také poslední, na chvíli, nesoucí jméno Divné příběhy, protože Weinberg neobnovil licenci. Časopis byl retitled Worlds of Fantasy & Horrora číslování svazků bylo znovu zahájeno na svazku 1 číslo 1, ale v každém jiném případě se časopis nezměnil a čtyři čísla pod tímto názvem, vydaná v letech 1994 až 1996, jsou bibliografy považována za součást celkového Divné příběhy běh.[50]

V dubnu 1995 HBO oznámili, že mají v plánu obrátit se Divné příběhy do tří epizod antologie podobné jejich Příběhy z krypty série. Dohodu za práva usnadnili scenáristé Mark Patrick Carducci a Peter Atkins. Ředitelé Tim Burton, Francis Ford Coppola, a Oliver Stone byli výkonnými producenty a každý z nich měl režírovat epizodu. Stone měl být ředitelem pilota, ale série se nikdy nedostala k uskutečnění.[52]

| Zima | Jaro | Léto | Podzim | Zima | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2009 | 353 | 354 | |||

| 2010 | 355 | 356 | |||

| 2011 | 357 | 358 | nn | ||

| 2012 | 359 | 360 | |||

| 2013 | 361 | ||||

| 2014 | 362 | ||||

| Problémy Divné příběhy od roku 2009 do roku 2014, ukazující objem a čísla vydání. Číslo označené „nn“ nebylo očíslováno; byla to ukázková kopie rozdaná na World Fantasy Convention. Redaktory byli Vandermeer (šedý); Segal (modrý); a Kaye (lila).[39] | |||||

V roce 1997 se neobjevily žádné problémy, ale v roce 1998 Scithers a Schweitzer vyjednali dohodu s Warrenem Lupinem z Publikace DNA což jim umožnilo začít publikovat Divné příběhy znovu na základě licence. První číslo bylo vydáno v létě 1998 a kromě vynechání čísla Zima 1998 byl zachován pravidelný čtvrtletní harmonogram na další čtyři a půl roku. Prodeje byly slabé, nikdy se nezvýšily nad 6 000 kopií a DNA začala mít finanční potíže. Wildside Press, vlastněný Johnem Betancourtem, se připojil k DNA a Terminus Publishing jako spoluvydavatel, počínaje číslem červenec / srpen 2003, a Divné příběhy na několik měsíců se vrátil k většinou pravidelnému rozvrhu. Dlouhá pauza skončila vydáním z prosince 2004, které se objevilo počátkem roku 2005; toto bylo poslední vydání v rámci dohody s DNA. Wildside Press poté koupil Divné příběhya Betancourt se znovu připojil k Scithersovi a Schweitzerovi jako spoledaktor.[39][50]

První vydání Wildside Press vyšlo v září 2005 a počínaje následujícím číslem, datovaným únorem 2006, si časopis po určitou dobu udržel víceméně dvouměsíční plán. Na začátku roku 2007 oznámil Wildside předělání Divné příběhy, pojmenování Stephen H. Segal redakční a kreativní ředitel a později nábor Ann VanderMeer jako nový redaktor beletrie.[43] V lednu 2010 časopis oznámil, že Segal opouští hlavní redaktorský post, aby se stal redaktorem Quirk Books. VanderMeer byl povýšen na šéfredaktora, Mary Robinette Kowal připojil se k personálu jako umělecký ředitel a Segal se stal hlavním redaktorem.[53]

23. srpna 2011, John Betancourt oznámil, že Wildside Press bude prodávat Divné příběhy Marvin Kaye a John Harlacher z Nth Dimension Media. Marvin Kaye převzal šéfredaktorské povinnosti. Číslo 359, první v rámci nových vydavatelů, bylo vydáno koncem února 2012. Několik měsíců před vydáním čísla 359 bylo zdarma vydáno speciální vydání náhledu World Fantasy Convention pro zájemce.[54][55][56][57] Poté se objevily čtyři čísla, přičemž číslo # 362 bylo zveřejněno na jaře roku 2014.[58]

14. srpna 2019 oficiální Divné příběhy Časopis Facebook oznámil návrat Divné příběhy s autorem Jonathan Maberry jako redakční ředitel. Vydání # 363 bylo k dispozici ke koupi na Divné příběhy webová stránka.[59]

Obsah a příjem

Henneberger dal Divné příběhy podtitul „The Unique Magazine“ z prvního čísla. Henneberger doufal v podání „off-trail“ nebo neobvyklého materiálu. Později si vzpomněl na rozhovor se třemi známými spisovateli z Chicaga, Hamlin Garland, Emerson Hough, a Ben Hecht, z nichž každý řekl, že se vyhýbali psaní příběhů „fantasy, bizarní a outré“[10] z důvodu pravděpodobnosti odmítnutí stávajícími trhy. Dodal: „Přiznám se, že hlavním motivem je založení Divné příběhy bylo dát spisovateli volnou ruku, aby vyjádřil své nejniternější pocity způsobem, který odpovídá velké literatuře “.[10]

Edwin Baird

Edwin Baird, první redaktor časopisu Divné příběhy, nebyl pro tuto práci ideální volbou, protože neměl rád hororové příběhy; jeho odbornost byla v krimi a většina materiálu, který získal, byla nevýrazná a neoriginální.[9][10] Spisovatelé, které Henneberger doufal, že zveřejní, například Garland a Hough, nepředložili Bairdovi nic a časopis publikoval převážně tradiční beletrii duchů, přičemž mnoho příběhů bylo vyprávěno postavami v bláznivých blázincích nebo vyprávěno ve formátu deníku.[61][62] Úvodní příběh prvního čísla byl „Ooze“, autor Anthony M. Rud; tam byl také první pokračování seriálu "Věc tisíce tvarů", od Otis Adelbert Kline, a 22 dalších příběhů. Ashley navrhuje, aby se lepším spisovatelům buničiny, od nichž se Bairdovi podařilo získat materiál, například Francis Stevens a Austin Hall posílali Bairdovi příběhy, které už byly jinde odmítnuty.[63]

V polovině roku dostal Baird pět příběhů od H. P. Lovecrafta; Baird je koupil všech pět. Lovecraft, kterého přátelé přesvědčili, aby příběhy předložil, přiložil průvodní dopis, který byl tak pozoruhodně negativní ohledně kvality rukopisů, že jej Baird publikoval ve vydání ze září 1923, s připojenou poznámkou, že příběhy koupil “ navzdory výše uvedenému nebo kvůli tomu “.[64] Baird však trval na tom, aby byly příběhy znovu odeslány jako rukopisy s dvojitým řádkováním; Lovecraftovi se psaní nelíbilo a zpočátku se rozhodl znovu odeslat pouze jeden příběh, “Dagon ".[64] Objevil se v čísle z října 1923, které bylo nejpozoruhodnější z Bairdova působení, protože zahrnovalo příběhy tří autorů, kteří by se stali častými přispěvateli do Divné příběhy: stejně jako Lovecraft označil první vystoupení v časopise Frank Owen a Seabury Quinn.[14][63]

Robert Weinberg, ve své historii Divné příběhy, souhlasí s Ashley, že kvalita Bairdových čísel byla špatná, ale poznamenává, že byly zveřejněny některé dobré příběhy: „jen to, že procento těchto příběhů bylo nepatrně malé“.[62] Weinberg vyzdvihuje „A Square of Canvas“ od Ruda a „Beyond the Door“ od Paula Sutera jako „výjimečný“;[62] oba se objevili ve vydání z dubna 1923. Weinberg také považuje „The Floor Above“ od M. L. Humphriesa a „Penelope“ od Vincent Starrett „jak z čísla z května 1923, tak„ Lucifer “od Johna Swaina, z čísla z listopadu 1923, jako nezapomenutelné, a uvádí, že„Krysy ve zdech „, v čísle z března 1924, byl jedním z nejlepších příběhů Lovecrafta. Není jasné, zda za nákup příběhů Lovecrafta byl zodpovědný Baird nebo Henneberger; v jednom z dopisů Lovecrafta objasňuje, že Baird chtěl získat jeho příběhy, ale Henneberger má řekl, že přemohl Bairda a že Bairdovi se nelíbilo Lovecraftovo psaní.[65] Byl to Henneberger, kdo přišel s dalším nápadem týkajícím se Lovecrafta: Henneberger kontaktoval Harry Houdini a zařídil, aby mu Lovecraftův duch napsal příběh pomocí zápletky dodané Houdinim. Příběh, "Vězněn s faraony “, objevil se pod Houdiniho jménem v čísle květen / červen / červenec 1924, přestože byl téměř ztracen - Lovecraft nechal napsaný rukopis ve vlaku, kterým se vydal do New Yorku, aby se oženil, a proto strávil většinu svého svatebního dne přepisováním rukopis z rukopisné kopie, kterou stále měl.[66][67]

Vydání květen / červen / červenec 1924 obsahovalo další příběh: „The Loved Dead ", od C. M. Eddy Jr. který zahrnoval zmínku o nekrofilie.[68][69] Podle Eddyho to vedlo k odstranění časopisu z novinových stánků v několika městech a prospěšné publicitě časopisu, což napomohlo prodeji, ale v jeho historii Divné příběhy Robert Weinberg uvádí, že nenalezl žádné důkazy o zákazu časopisu a finanční stav časopisu naznačuje, že ani prodej neměl žádnou výhodu.[68] S. T. Joshi však uvedl, že časopis byl skutečně odstraněn z novinových stánků v Indianě.[70]

Obal během Bairdova působení byl nudný; Ashley tomu říká „neatraktivní“,[9] a Weinberg popisuje barevné schéma obálky prvního čísla jako „méně než inspirované“, ačkoli obálku příštího měsíce považuje za vylepšení. Dodává, že od čísla z května 1923 „se pokrývky ponořily do jámy průměrnosti“. Podle Weinbergova názoru byla špatná obálka, často R. M. Mallyho, pravděpodobně částečně vinou neúspěchu časopisu pod Bairdem.[60] Weinberg také považuje interiérové umění během prvního ročníku časopisu za velmi slabé; většina interiérových kreseb byla malá a s malou atmosférou, kterou by člověk od hororového časopisu očekával. Všechny ilustrace pocházel od Heitmana, kterého Weinberg popisuje jako „... pozoruhodný jeho naprostým nedostatkem fantazie. Heitmanovou specializací bylo převzetí jeden scéna v děsivém příběhu, který neobsahoval vůbec nic děsivého nebo divného a ilustrujícího to “.[71][72]

Farnsworth Wright

Nový redaktor Farnsworth Wright byl mnohem ochotnější než Baird publikovat příběhy, které se nehodily do žádné ze stávajících kategorií buničiny. Ashley ve svém výběru popisuje Wrighta jako „nevyzpytatelného“, ale pod jeho vedením se kvalita časopisu neustále zlepšovala.[74] Jeho první vydání, listopad 1924, bylo o málo lepší než vydání Bairda, ačkoli obsahovalo dva příběhy nových autorů, Frank Belknap Long a Greye La Spina, kteří se stali oblíbenými přispěvateli.[75] V následujícím roce založil Wright skupinu pravidelných spisovatelů, včetně Longa a La Spiny, a publikoval mnoho příběhů spisovatelů, kteří budou s časopisem úzce spojeni na další desetiletí a další. V dubnu 1925 Nictzin Dyalhis objevil se první příběh „Když zelená hvězda ubývala“; ačkoli Weinberg to považuje za velmi zastaralé, v té době to bylo velmi pokládané, Wright jej v roce 1933 uvedl jako nejpopulárnější příběh, který se objevil v Divné příběhy. Toto vydání obsahovalo také první díl románu La Spiny Útočníci ze tmy, což Baird odmítl jako „příliš běžné“. Ukázalo se, že je u čtenářů velmi populární, a Weinberg poznamenává, že Bairdovo odmítnutí bylo „jen jednou z mnoha chyb, kterých se dopustil dřívější redaktor“.[76]

Arthur J. Burks, který se stal velmi úspěšným spisovatelem buničiny, se v lednu 1925 objevil pod svým skutečným jménem i pod pseudonymem, který se používal pro jeho první prodej. Robert Spencer Carr První příběh se objevil v březnu 1925; H. Warner Munn „Vlkodlak z Ponkertu“ se objevil v červenci 1925 a ve stejném čísle vytiskl Wright „Oštěp a tesák“, první profesionální prodej Robert E. Howard, který by se stal slavným jako tvůrce Barbar Conan.[76] Na konci roku 1925 Wright přidal „Divné příběhy dotisk “oddělení, které představilo staré podivné příběhy, obvykle hororové klasiky. Často to byly překlady a v některých případech vzhled v Divné příběhy bylo první vystoupení příběhu v angličtině.[77]

Wright původně odmítl Lovecraftův „Volání Cthulhu „, ale nakonec jej koupil a vytiskl ve vydání z února 1928.[78] Jednalo se o první příběh o Cthulhu Mythos, fiktivní vesmír, ve kterém Lovecraft uvedl několik příběhů. Postupem času začali další autoři přispívat svými vlastními příběhy se stejným společným pozadím, například Frank Belknap Long, August Derleth, E. Hoffmann Cena, a Donald Wandrei. Robert E. Howard a Clark Ashton Smith byli přátelé Lovecrafta, ale nepřispěli příběhy Cthulhu; místo toho napsal Howard meč a čarodějnictví fiction, a Smith produkoval sérii vysoká fantazie příběhy, z nichž mnohé byly součástí jeho Hyperborejský cyklus.[74] Robert Bloch, později se stal známým jako spisovatel filmu Psycho, začal publikovat příběhy v Divné příběhy v roce 1935; byl fanouškem Lovecraftovy práce a požádal Lovecraft o svolení zahrnout Lovecraft jako postavu do jednoho ze svých příběhů a zabít postavu. Lovecraft mu dal svolení a krátce nato mu to odplatil tím, že v jednom ze svých vlastních příběhů zabil řídce maskovanou verzi Blocha.[79][poznámky 6] Edmond Hamilton, přední raný spisovatel vesmírná opera, se stal pravidelným a Wright také publikoval sci-fi příběhy od J. Schlossel a Otis Adelbert Kline.[61] Tennessee Williams „první prodej byl Divné příběhy, s povídkou s názvem „Pomsta Nitocris Toto bylo zveřejněno v čísle ze srpna 1928 pod skutečným jménem autora Thomase Laniera Williamse.[81]

Divné příběhy„Podtitul byl„ The Unique Magazine “a Wrightovy výběry příběhů byly tak rozmanité, jak sliboval podtitul;[4] byl ochoten tisknout podivné nebo bizarní příběhy bez náznaku fantastických, pokud byly dost neobvyklé, aby se vešly do časopisu.[77] Although Wright's editorial standards were broad, and although he personally disliked the restrictions that convention placed on what he could publish, he did exercise caution when presented with material that might offend his readership.[74][82] E. Hoffmann Price records that his story "Stranger from Kurdistan" was held after purchase for six months before Wright printed it in the July 1925 issue; the story includes a scene in which Christ and Satan meet, and Wright was worried about the possible reader reaction. The story nevertheless proved to be very popular, and Wright reprinted it in the December 1929 issue. He also published "The Infidel's Daughter" by Price, a satire of the Ku-Klux-Klan, which drew an angry letter and a cancelled subscription from a Klan member. Price later recalled Wright's response: "a story that arouses controversy is good for circulation ... and anyway it would be worth a reasonable loss to rap bigots of that caliber".[82] Wright also printed George Fielding Eliot 's "The Copper Bowl", a story about a young woman being tortured; she dies when her torturer forces a rat to eat through her body. Weinberg suggests that the story was so gruesome that it would have been difficult to place in a magazine even fifty years later.[83]

On several occasions Wright rejected a story of Lovecraft's only to reconsider later; de Camp suggests that Wright's rejection at the end of 1925 of Lovecraft's "V trezoru ", a story about a mutilated corpse taking revenge on the undertaker responsible, was because it was "too gruesome", but Wright changed his mind a few years later, and the story eventually appeared in April 1932.[84] Wright also rejected Lovecraft's "Bránami stříbrného klíče " in mid-1933. Price had revised the story before passing it to Wright, and after Wright and Price discussed the story, Wright bought it, in November of that year.[85] Wright turned down Lovecraft's novel V horách šílenství in 1935, though in this case it was probably because of the story's length—running a serial required paying an author for material that would not appear until two or three issues later, and Divné příběhy often had little cash to spare. In this case he did not change his mind.[86]

Quinn was Divné příběhy' most prolific author, with a long-running sequence of stories about a detective, Jules de Grandin, who investigated supernatural events, and for a while he was the most popular writer in the magazine.[poznámky 7] Včetně dalších pravidelných přispěvatelů Paul Ernst, David H. Keller, Greye La Spina, Hugh B. Jeskyně, and Frank Owen, who wrote fantasies set in an imaginary version of the Far East.[74] C.L. Moore 's story "Shambleau ", her first sale, appeared in Divné příběhy in November 1933; Price visited the Divné příběhy offices shortly after Wright read the manuscript for it, and recalls that Wright was so enthusiastic about the story that he closed the office, declaring it "C.L. Moore day".[88] The story was very well received by readers, and Moore's work, including her stories about Jirel z Joiry a Northwest Smith, appeared almost exclusively in Divné příběhy během příštích tří let.[74][89]

As well as fiction, Wright printed a substantial amount of poetry, with at least one poem included in most issues. Originally this often included reprints of poems such as Edgar Allan Poe „“El Dorado ", but soon most of the poetry was original, with contributions coming from Lovecraft, Howard, and Clark Ashton Smith, among many others.[90][91][92] Lovecraft's contributions included ten of his "Houby z Yuggoth " poems, a series of sonnets on weird themes that he wrote in 1930.[93]

The artwork was an important element of the magazine's personality, with Margaret Brundage, who painted many covers featuring nudes for Divné příběhy, perhaps the best known artist.[74] Many of Brundage's covers were for stories by Seabury Quinn, and Brundage later commented that once Quinn realized that Wright always commissioned covers from Brundage that included a nude, "he made sure that each de Grandin story had at least one sequence where the heroine shed all her clothes".[94] For over three years in the early 1930s, from June 1933 to August/September 1936, Brundage was the only cover artist Divné příběhy použitý.[94][95] Another prominent cover artist was J. Allen St. John, whose covers were more action-oriented, and who designed the title logo used from 1933 until 2007.[74] Hannes Bok 's first professional sale was to Divné příběhy, for the cover of the December 1939 issue; he became a frequent contributor over the next few years.[96]

Virgil Finlay, one of the most important figures in the history of science fiction and fantasy art, made his first sale to Wright in 1935; Wright only bought one interior illustration from Finlay at that time because he was concerned that Finlay's delicate technique would not reproduce well on pulp paper. After a test print on pulp stock demonstrated that the reproduction was more than adequate,[97] Wright began to buy regularly from Finlay, who became a regular cover artist for Divné příběhy starting with the December 1935 issue.[98] Demand from readers for Finlay's artwork was so high that in 1938 Wright commissioned a series of illustrations from Finlay for lines taken from famous poems, such as "O sweet and far, from cliff and scar/The horns of Elfland faintly blowing", from Tennyson's "Princezna ".[99] Not every artist was as successful as Brundage and Finlay: Price suggested that Curtis Senf, who painted 45 covers early in Wright's tenure, "was one of Sprenger's bargains", meaning that he produced poor art, but worked fast for low rates.[100]

During the 1930s, Brundage's rate for a cover painting was $90. Finlay received $100 for his first cover, which appeared in 1937, over a year after his first interior illustrations were used; Weinberg suggests that the higher fee was partly to cover postage, since Brundage lived in Chicago and delivered her artwork in person, but it was also because Brundage's popularity was beginning to decline. When Delaney acquired the magazine in late 1938, the fee for a cover painting was cut to $50, and in Weinberg's opinion the quality of the artwork declined immediately. Nudes no longer appeared, though it is not known if this was a deliberate policy on Delaney's part. In 1939 a campaign by Fiorello LaGuardia, the mayor of New York, to eliminate sex from the pulps led to milder covers, and this may also have had an effect.[101]

In 1936, Howard committed suicide, and the following year Lovecraft died.[102] There was so much unpublished work by Lovecraft [poznámky 8] that Wright was able to use that he printed more material under Lovecraft's byline after his death than before.[103] In Howard's case, there was no such trove of stories available, but other writers such as Henry Kuttner provided similar material.[28] By the end of Wright's tenure as editor, many of the writers who had become strongly associated with the magazine were gone; Kuttner, and others such as Price and Moore, were still writing, but Weird Tales' rates were too low to attract submissions from them. Clark Ashton Smith had stopped writing, and two other writers who were well-liked, G.G. Pendarves and Henry Whitehead, zemřel.[102]

Except for a couple of short-lived magazines such as Zvláštní příběhy a Příběhy kouzel a tajemství, and a weak challenge from Duchařské historky, all between the late 1920s and the early 1930s, Divné příběhy had little competition for most of Wright's sixteen years as editor. In the early 1930s, a series of pulp magazines began to appear that became known as "divná hrozba " magazines. These lasted until the end of the decade, but despite the name there was little overlap in subject matter between them and Divné příběhy: the stories in the weird menace magazines appeared to be based on occult or supernatural events, but at the end of the tale the mystery was always revealed to have a logical explanation.[104] In 1935 Wright began running weird detective stories to try to attract some of the readers of these magazines to Divné příběhy, and asked readers to write in with comments. Reader reaction was uniformly negative, and after a year he announced that there would be no more of them.[105]

In 1939 two more serious threats appeared, both launched to compete directly for Divné příběhy' readers. Zvláštní příběhy appeared in February 1939 and lasted for just over two years; Weinberg describes it as "top-quality",[102] though Ashley is less complimentary, describing it as largely unoriginal and imitative.[106] The following month the first issue of Neznámý appeared from Street & Smith.[107] Fritz Leiber submitted several of his "Fafhrd a Šedý Mouser " stories to Wright, but Wright rejected all of them (as did McIlwraith when she took over the editorship). Leiber subsequently sold them all to John W. Campbell for Neznámý; Campbell commented each time to Leiber that "these would be better in Divné příběhy". The stories grew into a very popular sword and sorcery series, but none of them ever appeared in Divné příběhy. Leiber did eventually sell several stories to Divné příběhy, beginning with "The Automatic Pistol", which appeared in May 1940.[102][108]

Divné příběhy included a letters column, titled "The Eyrie", for most of its existence, and during Wright's time as editor it was usually filled with long and detailed letters. When Brundage's nude covers appeared, a lengthy debate over whether they were suitable for the magazine was fought out in the Eyrie, with the two sides divided about equally. For years it was the most discussed topic in the magazine's letter column. Many of the authors Wright published wrote letters too, including Lovecraft, Howard, Kuttner, Bloch, Smith, Quinn, Wellman, Price, and Wandrei. In most cases these letters praised the magazine, but occasionally a critical comment was raised, as when Bloch repeatedly expressed his dislike for Howard's stories of Conan the Barbarian, referring to him as "Conan the Cimmerian Chipmunk".[109] Another debate that was aired in the letter column was the question of how much science fiction the magazine should include. Dokud Úžasné příběhy was launched in April 1926, science fiction was popular with Divné příběhy' readers, but after that point letters began to appear asking Wright to exclude science fiction, and only publish weird fantasy and horror. The pro-science fiction readers were in the majority, and as Wright agreed with them, he continued to include science fiction in Divné příběhy.[110] Hugh B. Cave, who sold half-a-dozen stories to Wright in the early 1930s, commented on "The Eyrie" in a letter to a fellow writer: "No other magazine makes such a point of discussing past stories, and letting the authors know how their stuff is received".[111]

Dorothy McIlwraith

McIlwraith was an experienced magazine editor, but she knew little about weird fiction, and unlike Wright she also had to face real competition from other magazines for Divné příběhy' core readership.[102] Ačkoli Neznámý folded in 1943, in its four years of existence it transformed the field of fantasy and horror, and Divné příběhy was no longer regarded as the leader in its field. Neznámý published many successful humorous fantasy stories, and McIlwraith responded by including some humorous material, but Divné příběhy' rates were less than Neznámýje, with predictable effects on quality.[28][107] In 1940 the policy of reprinting horror and weird classics ceased, and Divné příběhy began using the slogan "All Stories New – No Reprints". Weinberg suggests that this was a mistake, as Divné příběhy' readership appreciated getting access to classic stories "often mentioned but rarely found".[113] Without the reprints Divné příběhy was left to survive on the rejects from Neznámý, with the same authors selling to both markets. In Weinberg's words, "only the quality of the stories [separated] their work between the two pulps".[113]

Delaney's personal taste also reduced McIlwraith's latitude. In an interview with Robert A. Lowndes in early 1940, Delaney spoke about his plans for Divné příběhy. After saying that the magazine would still publish "all types of weird and fantasy fiction", Lowndes reported that Delaney did not want "stories which center about sheer repulsiveness, stories which leave an impression not to be described by any other word than 'nasty'". Lowndes later added that Delaney had told him he found some of Clark Ashton Smith's stories on the "disgusting side".[114][poznámky 9]

McIlwraith continued to publish many of Weird Tales' most popular authors, including Quinn, Derleth, Hamilton, Bloch, and Manly Wade Wellman.[28] She also added new contributors; as well as publishing many of Ray Bradbury 's early stories, Divné příběhy regularly featured Fredric Brown, Mary Elizabeth Counselman, Fritz Leiber, a Theodore Sturgeon.[74] As Wright had done, McIlwraith continued to buy Lovecraft stories submitted by August Derleth, though she abridged some of the longer pieces, such as "Stín nad Innsmouthem ".[103] Sword and sorcery stories, a genre which Howard had made much more popular with his stories of Conan, Solomon Kane a Bran Mak Morn v Divné příběhy in the early 1930s, had continued to appear under Farnsworth Wright; they all but disappeared during McIlwraith's tenure. McIlwraith also focused more on short fiction, and serials and long stories were rare.[28][115]

In May 1951 Divné příběhy once again began to include reprints, in an attempt to reduce costs, but by that time the earlier issues of Divné příběhy had been extensively mined for reprints by August Derleth's publishing venture, Arkham House, and as a result McIlwraith often reprinted lesser-known stories. They were not advertised as reprints, which led in a couple of cases to letters from readers asking for more stories from H. P. Lovecraft, whom they believed to be a new author.[116]

In Weinberg's opinion, the magazine lost variety under McIlwraith's editorship, and "much of the uniqueness of the magazine was gone".[28] In Ashley's view, the magazine became more consistent in quality, rather than worse; Ashley comments that though the issues edited by McIlwraith "seldom attain[ed] Wright's highpoints, they also omitted the lows".[74] L. Sprague de Camp, towards the end of McIlwraith's time as editor, agreed that the 1930s were the magazine's heyday, citing Wright's death and the departure for other, better-paying, markets of several of its contributors as factors in the magazine's decline.[117]

Kvalita Divné příběhy' artwork suffered when Delaney cut the rates.[118] Bok, whose first cover had appeared in December 1939, moved to New York and joined the office art staff for a while; he eventually left because of the low pay. Boris Dolgov began contributing in the 1940s; he was a friend of Bok's and the two occasionally collaborated, signing the result "Dolbokgov". Weinberg regards Dolgov's illustration for Robert Bloch's "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper" as one of his best works.[119] Divné příběhy' paper was of very poor quality, which meant that the reproductions were poor, and along with the low pay rate for art this meant that many artists treated Divné příběhy as a last resort for their work.[120] Damon Knight, who sold some interior artwork to Divné příběhy in the early 1940s, recalled later that he was paid $5 for a single-page drawing, and $10 for a double-page spread; he worked slowly and the low pay meant Divné příběhy was not a viable market for him.[121]

The art editor, Lamont Buchanan, was able to establish five artists as regulars by the mid-1940s; they remained regular contributors until 1954, when the magazine's first incarnation ceased publication. The five were Dolgov, John Giunta, Fred Humiston, Vincent Napoli, a Lee Brown Coye.[120] In Weinberg's review of Divné příběhy' interior art, he describes Humiston's work as ranging "from bad to terrible", but he is more positive about the others. Napoli had worked for Divné příběhy from 1932 to the mid-1930s, when he began selling to the science fiction pulps, but his work for Povídky brought him back to Divné příběhy ve 40. letech 20. století. Weinberg speaks highly of both Napoli and Coye, whom Weinberg describes as "the master of the weird and grotesque illustration". Coye did a series of full-page illustrations for Divné příběhy called "Weirdisms", which ran intermittently from November 1948 to July 1951.[122][123][124]

The letter column, "The Eyrie", was much reduced in size during McIlwraith's tenure, but as a gesture to the readers a "Divné příběhy Club" was started. Joining the Club simply meant writing in to receive a free membership card; the only other benefit was that the magazine listed all the members' names and addresses, so that members could contact each other. Among the names listed in the January 1943 issue was that of Hugh Hefner, later to become famous as the founder of Playboy.[125]

Towards the end of McIlwraith's time as editor a couple of new writers appeared, including Richard Matheson a Joseph Payne Brennan.[74] Brennan had already sold over a dozen stories to other pulps when he finally made a sale to McIlwraith, but he had always wanted to sell to Divné příběhy, and three years after the magazine folded he launched a small-press horror magazine named Děsný, which he published for some years, in imitation of Divné příběhy.[126]

Moskowitz, Carter, and Bellerophon

The four issues edited by Sam Moskowitz in the early 1970s were mostly notable for a detailed biography of William Hope Hodgson, serialized over three issues, along with some rare stories of Hodgson's that Moskowitz had unearthed. Many of the other stories were reprints, either from Divné příběhy or from other early pulps such as Černá kočka nebo Modrá kniha. In Ashley's opinion, the magazine "had the feel of a museum piece with nothing new or progressive", though Weinberg describes the magazine as having "an interesting jumble of contents".[127] The subsequent paperback series edited by Lin Carter was criticized in similar terms: Weinberg regards it as having "too much reliance ... on the old names like Lovecraft, Howard and Smith by reprinting mediocre material ... New writers were not sufficiently encouraged",[127] though Weinberg does add that Ramsey Campbell, Tanith Lee a Steve Rasnic Tem were among the newer writers who contributed good material.[127] Ashley's opinion of the two Bellerophon issues is low: he describes them as lacking "any clear editorial direction or acumen".[48]

Wildside Press and after

The April/May 2007 edition featured the magazine's first all-new design in almost seventy-five years. During the next few years, Divné příběhy published works by a wide range of strange-fiction authors including Michael Moorcock and Tanith Lee, as well as newer writers such as Jay Lake, Kočka Rambo, a Rachel Swirsky.[43] The period also saw the addition of a broader range of content, ranging from narrative essays to comics to features on weird culture. The magazine won its first Cena Hugo in August 2009, in the semiprozine category,[128] two Hugo Award nominations in subsequent years,[129] and its first World Fantasy Award nomination, for editors Segal and Vandermeer, in more than seventeen years.[129][130]

V srpnu 2012 Divné příběhy became involved in a media altercation after the editor announced the magazine was going to publish an excerpt from Victoria Foyt 's controversial novel Save the Pearls, which many critics accused of featuring racist stereotypizace. The decision was made despite the protests of VanderMeer, and prompted her to end her association with the magazine.[131] The publisher subsequently overruled the editor, and announced that Divné příběhy no longer had plans to run the excerpt.[132]

Dědictví

Divné příběhy was one of the most important magazines in the fantasy field; in Ashley's view, it is "second only to Neznámý in significance and influence".[4] Weinberg goes further, calling it "the most important and influential of all fantasy magazines". Weinberg argues that much of the material Divné příběhy published would never have appeared if the magazine had not existed. Bylo to hotové Divné příběhy that Lovecraft, Howard, and Clark Ashton Smith became widely known, and it was the first and one of the most important markets for weird and science fantasy artwork. Many of the horror stories adapted for early radio shows such as Zůstaňte naladěni na teror původně se objevil v Divné příběhy.[3] The magazine's "Golden Age" was under Wright, and de Camp argues that one of Wright's accomplishments was to create a "Divné příběhy school of writing".[133] Justin Everett and Jeffrey H. Shanks, the editors of a recent scholarly collection of literary criticism focused on the magazine, argue that "Divné příběhy functioned as a nexus point in the development of speculative fiction from which emerged the modern genres of fantasy and horror".[134]

The magazine was, unusually for a pulp, included by the editors of the annual Year in Fiction anthologies, and was generally regarded with more respect than most of the pulps. This remained true long after the magazine's first run ended, as it became the main source of fantasy short stories for anthologists for several decades.[135] Weinberg argues that the fantasy pulps, of which, in his opinion, Divné příběhy was the most influential, helped to form the modern fantasy genre, and that Wright, "if he was not a perfect editor ... was an extraordinary one, and one of the most influential figures in modern American fantasy fiction",[136] a dodává to Divné příběhy and its competitors "served as the bedrock upon which much of modern fantasy rests".[137] Everett and Shanks agree, and regard Divné příběhy as the venue where writers, editors and an engaged readership "elevated speculated fiction to new heights" with influence that "reverberates through modern popular culture".[138] In Ashley's words, "somewhere in the imagination reservoir of all U.S. (and many non-U.S.) genre-fantasy and horror writers is part of the spirit of Divné příběhy".[5]

Bibliografické údaje

Redakční posloupnost v Divné příběhy was as follows:[11][140]

| Editor | Problémy |

|---|---|

| Edwin Baird | March 1923 – May/June/July 1924 |

| Farnsworth Wright | November 1924 – March 1940 |

| Dorothy McIlwraith | May 1940 – September 1954 |

| Sam Moskowitz | April 1973 – Summer 1974 |

| Lin Carter | Spring 1981 – Summer 1983 |

| Forrest J Ackerman /Gil Lamont | Podzim 1984 |

| Gordon Garb | Zima 1985 |

| Darrell Schweitzer | Spring 1988 – Winter 1990 September 2005 – February/March 2007 |

| Darrell Schweitzer | Spring 1991 – Winter 1996/1997 |

| Darrell Schweitzer George Scithers | Summer 1998 – December 2004 |

| Stephen Segal | April/May 2007 – September/October 2007 Jaro 2010 |

| Ann VanderMeer | November/December 2007 – Fall 2009 Summer 2010 – Winter 2012 |

| Marvin Kaye | Fall 2012 – Spring 2014 |

| Jonathan Maberry | Summer 2019 – present |

The publisher for the first year was Rural Publishing Corporation; this changed to Popular Fiction Publishing with the November 1924 issue, and to Weird Tales, Inc. with the December 1938 issue. The four issues in the early 1970s came from Renown Publications, and the four paperbacks in the early 1980s were published by Zebra Books. The next two issues were from Bellerophon, and then from Spring 1988 to Winter 1996 the publisher was Terminus. From Summer 1998 to July/August 2003 the publisher was DNA Publications and Terminus, listed either as DNA Publications/Terminus or just as DNA Publications. The September/October 2003 issue listed the publisher as DNA Publications/Wildside Press/Terminus, and through 2004 this remained the case, with one issue dropping Terminus from the masthead. Thereafter Wildside Press was the publisher, sometimes with Terminus listed as well, until the September/October 2007 issue, after which only Wildside Press were listed. The issues published from 2012 through 2014 were from Nth Dimension Media.[11][140]

Divné příběhy was in pulp format for its entire first run except for the issues from May 1923 to April 1924, when it was a large pulp, and the last year, from September 1953 to September 1954, when it was a digest. The four 1970s issues were in pulp format. The two Bellerophon issues were kvarto. The Terminus issues reverted to pulp format until the Winter 1992/1993 issue, which was large pulp. A single pulp issue appeared in Fall 1998, and then the format returned to large pulp until the Fall 2000 issue, which was quarto. The format varied between large pulp and quarto until January 2006, which was large pulp, as were all issues after that date until Fall 2009, except for a quarto-sized November 2008. From Summer 2010 the format was quarto.[11][140]

The first run of the magazine was priced at 25 cents for the first fifteen years of its life except for the oversized May/June/July 1924 issue, which was 50 cents. In September 1939 the price was reduced to 15 cents, where it stayed until the September 1947 issue, which was 20 cents. The price went up again to 25 cents in May 1949; the digest-sized issues from September 1953 to September 1954 were 35 cents. The first three paperbacks edited by Lin Carter were priced at $2.50; the fourth was $2.95. The two Bellerophon issues were $2.50 and $2.95. The Terminus Divné příběhy began in Spring 1988 priced at $3.50; this went up to $4.00 with the Fall 1988 issue, and to $4.95 with the Summer 1990 issue. The next price increase was to $5.95, in Spring 2003, and then to $6.99 with the January 2008 issue. The first two issues from Nth Dimension Media were priced at $7.95 and $6.99; the last two were $9.99 each.[11][140]

Some of the early Terminus editions of Divné příběhy were also printed in hardcover format, in limited editions of 200 copies. These were signed by the contributors, and were available at $40 as part of a subscription offer. Issues produced in this format include Summer 1988, Spring/Fall 1989, Winter 1989/1990, Spring 1991, and Winter 1991/1992.[50][140]

Antologie

Starting in 1925, Christine Campbell Thomson edited a series of horror story anthologies, published by Selwyn and Blount s názvem Not at Night. These were considered an unofficial U.K. edition of the magazine, with the stories sometimes appearing in the anthology before the magazine's U.S. version appeared. The ones which drew a substantial fraction of their contents from Divné příběhy byly:[141][142]

| Rok | Titul | Příběhy z Divné příběhy |

|---|---|---|

| 1925 | Not at Night | Všech 15 |

| 1926 | More Not at Night | Všech 15 |

| 1927 | You'll Need a Night Light | 14 z 15 |

| 1929 | By Daylight Only | 15 z 20 |

| 1931 | Switch on the Light | 8 z 15 |

| 1931 | At Dead of Night | 8 z 15 |

| 1932 | Grim Death | 7 z 15 |

| 1933 | Keep on the Light | 7 z 15 |

| 1934 | Teror v noci | 9 z 15 |

There was also a 1937 anthology titled Not at Night Omnibus, which selected 35 stories from the Not at Night series, of which 20 had originally appeared in Divné příběhy. In the U.S. an anthology titled Not at Night!, edited by Herbert Asbury, appeared from Macy-Macius v roce 1928; this selected 25 stories from the series, with 24 of them drawn from Divné příběhy.[141]

Numerous other anthologies of stories from Divné příběhy have been published, including:[43][143][144][145][146][147][148][149][150][151][152]

| Rok | Titul | Editor | Vydavatel | Poznámky |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1961 | Neočekávaný | Leo Margulies | Pyramida | |

| 1961 | The Ghoul Keepers | Leo Margulies | Pyramida | |

| 1964 | Divné příběhy | Leo Margulies | Pyramida | Ghost edited by Sam Moskowitz |

| 1965 | Worlds of Weird | Leo Margulies | Pyramida | Ghost edited by Sam Moskowitz |

| 1976 | Divné příběhy | Peter Haining | Neville Spearman | The hardback edition (but not the paperback) reproduces the original stories in facsimile[153] |

| 1977 | Weird Legacies | Mike Ashley | Hvězda | |

| 1988 | Weird Tales: The Magazine That Never Dies | Marvin Kaye | Nelson Doubleday | |

| 1995 | The Best of Weird Tales | John Betancourt | Barnes & Noble | |

| 1997 | The Best of Weird Tales: 1923 | Marvin Kaye & John Betancourt | Bleak House | |

| 1997 | Weird Tales: Seven Decades of Terror | John Betancourt & Robert Weinberg | Barnes & Noble | |

| 2020 | The Women of Weird Tales | Melanie Anderson | Knihy Valancourt |

Kanadské a britské vydání

| Jan | Února | Mar | Dubna | Smět | Červen | Jul | Srpen | Září | Října | listopad | Prosinec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1942 | 36/3 | 36/4 | 37/1 | 37/1 | ||||||||

| 1943 | 36/7 | 36/8 | 36/9 | 36/10 | 37/11 | 36/12 | ||||||

| 1944 | 36/13 | 36/14 | 36/15 | 36/15 | 37/5 | 37/6 | ||||||

| 1945 | 38/1 | 38/3 | 38/3 | 38/3 | 38/3 | 38/3 | ||||||

| 1946 | 38/3 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | ||||||

| 1947 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | 38/4 | ||||||

| 1948 | nn | 40/3 | 40/4 | 40/5 | 40/6 | 41/1 | ||||||

| 1949 | 41/2 | 41/3 | 41/4 | 41/5 | 41/6 | 42/1 | ||||||

| 1950 | 42/2 | 42/3 | 42/4 | 42/5 | 42/6 | 43/1 | ||||||

| 1951 | 43/2 | 43/3 | 43/4 | 43/5 | 43/6 | 44/1 | ||||||

| Canadian issues of Divné příběhy from 1941 to 1954, showing volume/issue number. "nn" indicates that that issue had no number. The numerous oddities in volume numbering are correctly shown.[154] | ||||||||||||

A Canadian edition of Divné příběhy appeared from June 1935 to July 1936; all fourteen issues are thought to be identical to the U.S. issues of those dates, though "Printed in Canada" appeared on the cover, and in at least one case another text box was placed on the cover to conceal part of a nude figure. Another Canadian series began in 1942, as a result of import restrictions placed on U.S. magazines. Canadian editions from 1942 up to January 1948 were not identical to the U.S. editions, but they match closely enough that the originals are easily identified. From the May 1942 to January 1945 issues, they correspond to the U.S. editions two issues earlier, that is, from January 1942 to September 1944. There was no Canadian issue corresponding to the November 1944 U.S. issue, so from that point the Canadian issues were only one behind the U.S. ones: the issues from March 1945 to January 1948 correspond to the U.S. issues from January 1945 to November 1947. There was no Canadian issue of the January 1948 U.S. issue, and from the next issue, March 1948, till the end of the Canadian run in November 1951, the issues were identical to the U.S. versions.[155]

There were numerous differences between the Canadian issues from May 1942 to January 1948 and the corresponding U.S. issues. All the covers were repainted by Canadian artists until the January 1945 issue; thereafter the artwork from the original issues was used. Initially the fiction content of the Canadian issues was unchanged from the U.S., but starting in September 1942 the Canadian Divné příběhy dropped some of the original stories in each issue, replacing them with either stories from other issues of Divné příběhy, or, occasionally, material from Povídky.[155]

In a couple of instances a story appeared in the Canadian edition of the magazine before its appearance in the U.S. version, or simultaneously with it, so it is evident that whoever assembled the issues had access to the Divné příběhy pending story file. Because of the reorganization of material, it often happened that one of the Canadian issues would have more than a single story by the same author. In these cases a pseudonym was invented for one of the stories.[155]

There were four separate editions of Divné příběhy distributed in the United Kingdom. In early 1942, three issues abridged from the September 1940, November 1940, and January 1941 U.S. issues were published in the U.K. by Gerald Swan; they were undated, and had no volume numbers. The middle issue was 64 pages long; the other two were 48 pages. All were priced at 6d. A single issue was released in late 1946 by William Merrett; it also was undated and unnumbered. It was 36 pages long, and was priced at 1/6. The three stories included came from the October 1937 U.S. issue.[153]

A longer run of 23 issues appeared between November 1949 and December 1953, from Thorpe and Porter. These were all undated; the first issue had no volume or issue number but subsequent issues were numbered sequentially. Most were priced at 1/-; issues 11 to 15 were 1/6. All were 96 pages long. The first issue corresponds to the July 1949 U.S. issue; the next 20 issues correspond to the U.S. issues from November 1949 to January 1953, and the final two issues correspond to May 1953 and March 1953, in that order. Another five bimonthly issues appeared from Thorpe and Porter dated November 1953 to July 1954, with the volume numbering restarted at volume 1 number 1. These correspond to the U.S. issues from September 1953 to May 1954.[153]

Sběratelství

Divné příběhy is widely collected, and many issues command very high prices. In 2008, Mike Ashley estimated the first issue to be worth £3,000 in excellent condition, and added that the second issue is much rarer and commands higher prices. Issues with stories by Lovecraft or Howard are very highly sought-after, with the October 1923 issue, containing "Dagon", Lovecraft's first appearance in Divné příběhy, fetching comparable prices to the first two issues.[157] The first few volumes are so rare that very few academic collections have more than a handful of these issues: Východní New Mexico University, the holder of a remarkably complete early science fiction archive, has "only a few scattered issues" from the early years, and the librarian recorded in 1983 that "dealers laugh when Eastern enquires about these".[158]

Prices of the magazine drop over the succeeding decades, with the McIlwraith issues worth far less than the ones edited by Wright. Ashley quotes the digest-sized issues from the end of McIlwraith's tenure as fetching £8 to £10 each as of 2008. The revived editions are not particularly scarce, with two exceptions. The two Bellerophon issues received such poor distribution that they fetch high prices: Ashley quotes a 2008 price of £40 to £50 for the first one, and twice that for the second one. The other valuable recent issues are the hardback versions of the Terminus Divné příběhy; Ashley gives prices of between £40 and £90, with some of the special author issues fetching a premium.[157]

Poznámky

- ^ Lin Carter gives the debt as $41,000, and adds that the original capital was "reputedly" $11,000, meaning that during Baird's tenure the magazine had lost $52,000.[14] L. Sprague de Camp quotes Henneberger's debt as "at least $43,000, and perhaps as much as $60,000".[15]

- ^ In the same letter to Long, the 34-year-old Lovecraft, who often affected the airs of an aged gentleman, declared "think of the tragedy of such a move for an aged antiquarian".[17][19]

- ^ Jack Williamson recalls that Divné příběhy was paying one cent per word, "rather more reliably" than Úžasné příběhy, in about 1931;[21] and Hugh Cave quotes one cent per word as the rate in early 1933.[22]

- ^ Ashley says Wright's health made it "impossible to continue", but Weinberg says Delaney let Wright go "in a move to further cut costs". However, in a later history of the magazine, Weinberg says that Wright, "who had been in bad health for many years, stepped down as editor", and does not give any other reason for his departure.[28][30][33]

- ^ Delaney had attempted to revive Povídky in 1956, but had only produced five issues; Margulies also tried to bring Povídky back, and kept it alive from December 1957 until August 1959.[40][41][42]

- ^ Bloch's story was "The Shambler From the Stars", which appeared in the September 1935 issue; Lovecraft's riposte was "The Haunter of the Dark", in December 1936.[79][80]

- ^ On a business trip to New Orleans, Quinn was taken to an upmarket brothel by his business associates, and discovered that the women who worked there were regular readers of Divné příběhy. When they discovered who he was, they offered him their services free-of-charge.[87]

- ^ The stories were submitted to Divné příběhy by August Derleth, who had corresponded with Lovecraft.[87]

- ^ Lowndes was later to discover that it was almost certainly Smith's story "The Coming of the White Worm" which Delaney was referring to; it was eventually published by Donald Wollheim in Míchání vědeckých příběhů.[114]

Reference

- ^ Jaffery & Cook (1985), str. 63.

- ^ John Locke, "The Birth of Weird" in The Thing's Incredible: The Secret Origins of Weird Tales (Off-Trail Publications, 2018).

- ^ A b Weinberg (1985a), pp. 730–731.

- ^ A b C Ashley (1997), str. 1000.

- ^ A b Ashley (1997), str. 1002.

- ^ A b Nicholls, Peter; Ashley, Mike (18. července 2012). "Buničina". Encyklopedie SF. Gollancz. Citováno 17. prosince 2014.

- ^ Murray (2011), s. 26.

- ^ John Locke, "The Pals" in The Thing's Incredible: The Secret Origins of Weird Tales (Off-Trail Publications, 2018).

- ^ A b C Ashley (2000), str. 41.

- ^ A b C d E Weinberg (1999a), pp. 3–4.

- ^ A b C d E F G h Weinberg (1985a), pp. 735–736.

- ^ A b C d E F G Weinberg (1999a), p. 4.

- ^ Ashley (2008), p. 25.

- ^ A b C Carter (1976), pp. 35–37.

- ^ de Camp (1975), p. 203.

- ^ Ashley (2000), str. 42.

- ^ A b Carter (1976), pp. 41–46.

- ^ de Camp (1975), pp. 203–204.

- ^ H. P. Lovecraft, letter to Frank Belknap Long, 1924-03-21; cited in Carter (1976), p. 43.

- ^ Jaffery & Cook (1985), pp. 41–42.

- ^ Williamson (1984), p. 78.

- ^ Cave (1994), p. 31.

- ^ "Time-Travelling with H.P. Lovecraft" in First World Fantasy Convention: Three Authors Remember (West Warwick, RI: Necronomicon Press), p. 8

- ^ A b C d E Weinberg (1999a), p. 5.

- ^ Wright (1927), table of contents.

- ^ Bleiler (1990), p. 66.

- ^ Ashley (1985a), pp. 454–456.

- ^ A b C d E F G h i j Weinberg (1985a), pp. 729–730.

- ^ Cave (1994), pp. 38, 41.

- ^ A b C d E F G h i j Weinberg (1999a), p. 6.

- ^

Additional data on Buchanan's tenure as editor was taken from market reports in Spisovatelský přehled a Autor a novinář. Other data points come from correspondence between Buchanan and contributors. - ^ Jones (2008), s. 857.

- ^ A b C d Ashley (2000), str. 140.

- ^ Harriet Bradfield, "New York Market Letter," Spisovatelský přehled, Duben 1945.

- ^ Harriet Bradfield, "New York Market Letter," Spisovatelský přehled, November 1949.

- ^ de Camp (1953), pp. 111–121.

- ^ Ashley (2005), pp. 72–73.

- ^ Doug Ellis, John Locke a John Gunnison. The Adventure House Guide to the Pulps (Silver Spring, MD: Adventure House, 2000), str. 300-301.

- ^ A b C d „Miskatonic University library Periodical Reading Room - Weird Tales“. www.yankeeclassic.com. Citováno 11. července 2016.

- ^ A b Ashley (2005), s. 162–164.

- ^ A b C d E Ashley (2007), str. 283.

- ^ Stephensen-Payne, Phil. „Časopis povídek“. www.philsp.com. Galaktická střední. Citováno 9. července 2016.

- ^ A b C d Ashley, Mike; Nicholls, Peter. „Kultura: Divné příběhy: SFE: Encyklopedie sci-fi“. sf-encyclopedia.com. Citováno 22. července 2016.

- ^ Ashley (2007), str. 284.

- ^ Ashley (1997), s. 1000–1003.

- ^ Weinberg (1985a), s. 732–734.

- ^ Ashley (2016), str. 110.

- ^ A b C Ashley (2016), s. 110–112.

- ^ Divné příběhy in Limbo (1984), str. 4.

- ^ A b C d E Ashley (2008), s. 34–36.

- ^ "Seznam úmluv | Světová úmluva o fantasy". www.worldfantasy.org. Citováno 10. července 2016.

- ^ Staff, Variety (10. dubna 1995). „Špičkové helmy v týmu„ Tales “... Sky-high Sly cena“. Archivovány od originál 20. února 2016. Citováno 28. srpna 2016.

- ^ „Tisková zpráva Weird Tales z ledna 2010“. Weirdtales.net. 25. ledna 2010. Archivováno od originál 25. srpna 2010. Citováno 16. září 2012.

- ^ Strock, Ian Randal (23. srpna 2011). „Marvin Kaye kupuje Divné příběhy; upraví to sám “. Rozsah SF. Archivovány od originál 10. července 2012.

- ^ Publikace, Locus. "Locus Online News» Kaye kupuje divné příběhy ". www.locusmag.com. Místo. Archivovány od originál 13. května 2016. Citováno 31. července 2016.

- ^ „Zvláštní vydání náhledu Světové fantasy úmluvy“. www.scribd.com. 16. ledna 2012. Archivovány od originál 20. ledna 2012. Citováno 16. září 2012.

- ^ Publikace, Locus. „Lois Tilton hodnotí krátkou beletrii, polovina listopadu 2012“. www.locusmag.com. Místo. Archivovány od originál 29. května 2016. Citováno 22. srpna 2013.

- ^ „Publikace: Weird Tales, jaro 2014“. www.isfdb.org. Citováno 31. července 2016.

- ^ „WEIRD TALES IS BACK! The magazine that ... - Weird Tales Magazine“. Facebook. 14. srpna 2019. Citováno 18. srpna 2019.

- ^ A b Weinberg (1999c), str. 62.

- ^ A b Weinberg (1985a), s. 727–728.