Izraelská socha - Israeli sculpture

Izraelská socha označuje sochařství vyrobené v Země Izrael od roku 1906, rokuŠkola Becalela uměleckých řemesel "(dnes nazvaná Bezalel Academy of Art and Design) byla založena. Proces krystalizace izraelského sochařství byl v každé fázi ovlivněn mezinárodním sochařstvím. V raném období izraelského sochařství byli většina jeho významných sochařů přistěhovalci do země Izrael a jejich umění bylo syntéza vlivu evropského sochařství na způsob, jakým se národní umělecká identita vyvinula v zemi Izrael a později ve státě Izrael Izrael.

Úsilí o rozvoj místního stylu sochařství začalo koncem 30. let 20. století vytvořením „Caananit "sochařství, které kombinovalo vlivy evropského sochařství s motivy převzatými z východu, zejména z Mezopotámie. Tyto motivy byly formulovány na národní úrovni a snažily se představit vztah mezi sionismem a půdou vlasti. Navzdory aspiracím abstraktního sochařství, které v Izraeli vzkvétalo v polovině 20. století pod vlivem hnutí „Nové horizonty“ a pokoušelo se představit sochařství, které mluví univerzálním jazykem, jejich umění obsahovalo mnoho prvků dřívějšího „kananitu“ "sochařství. V 70. letech se pod izraelským uměním a sochařstvím dostalo pod vlivem mezinárodního mnoho nových prvků konceptuální umění. Tyto techniky významně změnily definici sochařství. Tyto techniky navíc usnadňovaly vyjádření politického a sociálního protestu, který byl v izraelském sochařství doposud bagatelizován.

Dějiny

Pokus o nalezení původních izraelských zdrojů z 19. století pro vývoj „izraelského“ sochařství je problematický ze dvou hledisek. Nejprve umělcům i židovské společnosti v zemi Izrael chyběly národní sionistické motivy, které by v budoucnu doprovázely vývoj izraelského sochařství. To samozřejmě platí i pro nežidovské umělce stejného období. Zadruhé, výzkum dějin umění nenalezl sochařskou tradici ani mezi židovskými komunitami země Izrael, ani mezi arabskými či křesťanskými obyvateli tohoto období. Ve výzkumu, který provedli Yitzhak Einhorn, Haviva Peled a Yona Fischer, byly identifikovány umělecké tradice tohoto období, které zahrnují ornamentální umění náboženské (židovské a křesťanské) povahy, které bylo vytvořeno pro poutníky, a proto pro export i místní potřeby. Mezi tyto předměty patřily zdobené tablety, reliéfní mýdla, pečetě atd. S motivy vypůjčenými z větší části z tradice grafického umění.[1]

Ve svém článku „Zdroje izraelského sochařství“[2] Gideon Ofrat označil začátek izraelského sochařství za založení školy Becalel v roce 1906. Zároveň identifikoval problém ve snaze podat jednotný obraz této sochy. Důvodem byla různorodost evropských vlivů na izraelské sochařství a relativně malý počet sochařů v Izraeli, z nichž většina dlouhodobě pracovala v Evropě.

Zároveň byla dokonce i na Bezalel - umělecké škole založené sochařem - socha považována za menší umění a její studium se soustředilo na umění malby a umění grafiky a designu. Dokonce ani v „Novém Becalelu“, založeném v roce 1935, Sochařství nezaujalo významné místo. I když je pravda, že v nové škole bylo zřízeno oddělení sochařství, o rok později se zavřelo, protože na něj bylo pohlíženo jako na nástroj, který pomáhá studentům naučit se trojrozměrnému designu, a nikoli jako nezávislé oddělení. Na jeho místo oddělení keramiky[3] otevřel a vzkvétal. V těchto letech se konaly výstavy jednotlivých sochařů jak v Bezalelově muzeu, tak v Tel Avivském muzeu, ale šlo o výjimky, které nenaznačovaly obecný postoj k trojrozměrnému umění. Nejasný postoj umělecké instituce k sochařství bylo možné pociťovat v různých inkarnacích až do šedesátých let.

Rané sochařství v zemi Izrael

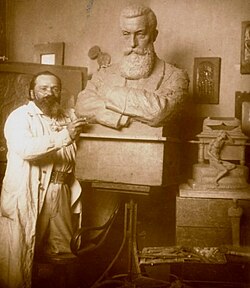

Začátek sochařství v zemi Izrael a izraelského umění obecně se obvykle označuje jako rok 1906, rok založení Bezalelské školy umění a řemesel v Jeruzalémě Boris Schatz. Schatz, který studoval sochařství v Paříži u Mark Antokolski, byl již známým sochařem, když dorazil do Jeruzaléma. Specializoval se na reliéfní portrétování židovských subjektů v akademickém stylu.

Schatzova práce se pokoušela nastolit novou židovsko-sionistickou identitu. Vyjádřil to použitím čísel z Bible v rámci odvozeném z evropské křesťanské kultury. Například jeho dílo „Matthew the Hasmoneum“ (1894) zobrazovalo židovského národního hrdinu Mattathias ben Johanan uchopil meč a nohou na těle řeckého vojáka. Tento druh reprezentace souvisí s ideologickým tématem „Vítězství dobra nad zlem“, jak je vyjádřeno například v postavě Perseuse v plastice z 15. století.[4] Dokonce i řada pamětních desek, které Schatz vytvořil pro vůdce židovského osídlení, pochází z klasického umění v kombinaci s popisnou tradicí v duchu tradice Ars Novo. Vliv klasických a Renesanční umění na Schatze lze vidět i na kopiích soch, které si objednal pro Bezalel, které vystavil v Bezalelově muzeu jako příklady ideálního sochařství pro studenty školy. Mezi tyto sochy patříDavide „(1473–1475) a„ Putto s delfínem “(1470) od Andrea del Verrocchio.[5]

Studie v Becalelu upřednostňovaly malbu, kresbu a design, a proto se ukázalo, že množství trojrozměrné plastiky bylo omezené. Mezi několika workshopy, které se ve škole otevřely, byl jeden v řezbářství, ve kterém byly vyráběny reliéfy různých sionistických a židovských vůdců, spolu s dílnami dekorativního designu v užitém umění s využitím technik, jako je kladivování mědi na tenké plechy, kladení drahokamů atd. slonová kost byl otevřen design, který také zdůrazňoval užité umění.[6] V průběhu jeho činnosti byly přidány workshopy, které fungovaly téměř autonomně. V poznámce vydané v červnu 1924 Schatz nastínil všechny hlavní oblasti činnosti Becalela, mezi nimi i kamennou plastiku, kterou založili především studenti školy v rámci „židovské legie“ a workshopu o řezbářství.[7]

Kromě Schatze bylo v Jeruzalémě v počátcích Bezalel několik dalších umělců, kteří pracovali v oblasti sochařství. V roce 1912 Ze'ev Raban emigroval do země Izrael na Schatzovo pozvání a působil jako instruktor sochařství, práce s měděnými plechy a anatomie v Bezcalelu. Raban trénoval sochařství na Akademii výtvarných umění v Mnichově a později na Ecole des Beaux-Arts v Paříž a Královská akademie výtvarných umění v Antverpy, Belgie. Kromě své známé grafické práce vytvořil Raban figurální plastiky a reliéfy v akademickém „orientálním“ stylu, jako je terakotová figurka biblických postav „Eli a Samuel“ (1914), kteří jsou líčeni jako jemenští Židé. Nejvýznamnější Rabanova práce se však zaměřila na reliéfy šperků a jiných dekorativních předmětů.[8]

Ostatní instruktoři v Bezalel také vytvořili sochy v realistickém akademickém stylu. Eliezer Strich například vytvořil busty lidí v židovské osadě. Další umělec, Jicchak Sirkin vyřezávané portréty do dřeva a kamene.

Hlavním příspěvkem k izraelskému sochařství tohoto období lze přispět k Abrahamovi Melnikoffovi, který pracoval mimo rámec Becalela. Melnikoff vytvořil své první dílo v Izraeli v roce 1919 poté, co přijel do země Izrael během své služby v „Židovská legie Až do třicátých let Melnikoff produkoval sérii plastik z různých druhů kamene, většinou portrétovaných v terakota a stylizované obrázky vytesané z kamene. Mezi jeho významná díla patří skupina symbolických soch zobrazujících probuzení židovské identity, například „The Awakening Judah“ (1925) nebo pamětní pomníky Ahad Ha'am (1928) a do Max Nordau (1928). Kromě toho Melnikoff předsedal prezentacím svých děl na výstavách Umělci země Izrael v Davidova věž.

Pomník „Řvoucí lev“ (1928–1932) navazuje na tento trend, ale tato socha je odlišná v tom, jak ji vnímala židovská veřejnost toho období. Melnikoff sám inicioval stavbu památníku a financování projektu získal společně Histadrut ha-Clalit, židovská národní rada a Alfred Mond (Lord Melchett). Obraz monumentální lev, vyřezávané do žuly, bylo ovlivněno primitivním uměním kombinovaným s mezopotámským uměním 7. a 8. století našeho letopočtu[9] Styl je vyjádřen především v anatomickém designu postavy.

Sochaři, kteří začali vyrábět díla na konci 20. a na počátku 30. let v izraelské zemi, prokázali širokou škálu vlivů a stylů. Mezi nimi bylo několik těch, kteří šli podle učení Becalelovy školy, zatímco jiní, kteří přišli po studiu v Evropě, přinesli s sebou vliv rané francouzské moderny na umění nebo vliv expresionismu, zejména v jeho německé podobě.

Mezi sochaři, kteří byli studenty Becalela, byla díla Aaron Priver vyčnívat. Priver přijel do země Izrael v roce 1926 a začal studovat sochařství u Melnikoffa. Jeho práce vykazovala kombinaci sklonu k realismu a archaického nebo mírně primitivního stylu. Jeho ženské postavy 30. let jsou navrženy se zaoblenými liniemi a povrchními rysy obličeje. Další žák, Nachum Gutman, lépe známý svými malbami a kresbami, cestoval do Vídeň v roce 1920, a později šel do Berlín a Paříž, kde studoval sochařství a grafiku a vyráběl sochy v malém měřítku, které vykazují stopy expresionismu a tendenci k „primitivnímu“ stylu v zobrazení jeho předmětů.

Práce David Ozeransky (Agam) pokračoval v dekorativní tradici Ze'ev Raban. Ozeransky dokonce pracoval jako dělník na sochařských dekoracích, které Raban vytvořil pro budovu YMCA v Jeruzalémě. Ozeranského nejdůležitějším dílem tohoto období je „Deset kmenů“ (1932) - skupina deseti čtvercových dekorativních desek, které symbolicky popisují deset kultur spojených s dějinami země Izrael. Další prací, kterou Ozeranzky během tohoto období vytvořil, byl „Lev“ (1935), který stojí na vrcholu budovy Generali v Jeruzalémě.[10]

Ačkoli nikdy nebyl studentem instituce, práce David Polus byl zakotven v židovském akademismu, který Schatz formuloval v Bezcalelu. Polus začal sochařit poté, co byl kamenářem v dělnickém sboru. Jeho prvním významným dílem byla socha „Davida pastýře“ (1936–1938) v roce Ramat David. V jeho monumentálním díle 1940 "Památník Alexandra Zeida “, která byla zalita do betonu u„ šejka Abreika “a stojí poblíž Beit She'arim Národní park Polus představuje muže známého jako „Strážný“ jako jezdec s výhledem na údolí Jezreel. V roce 1940 Polus umístil na základnu památníku dvě tablety v archaicko-symbolickém stylu, jejichž předměty byly „houští“ a „pastýř“.[11] I když je styl hlavní sochy realistický, stal se známým díky snaze oslavit svůj předmět a zdůraznit jeho spojení se zemí.

V roce 1910 sochařka Chana Orloff emigroval ze země Izrael do Francie a zahájil studium v École Nationale des Arts Décoratifs. Její práce, počínaje studiem, zdůrazňuje její vztah k francouzskému umění té doby. Obzvláště evidentní je vliv kubistické plastiky, která se s odstupem času v její práci zmírňovala. Její sochy, většinou lidské obrazy vytesané do kamene a dřeva, navržené jako geometrické prostory a plynulé linie. Významná část její práce je věnována sochařským portrétům postav francouzské společnosti.[12] Její spojení s izraelskou zemí si Orloff zachoval prostřednictvím výstavy svých děl v Tel Avivském muzeu.[13]

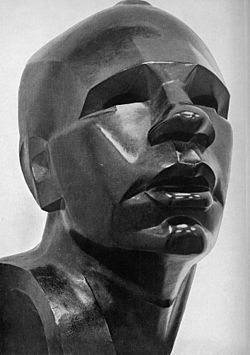

Další sochař, který byl velmi ovlivněn kubismem, je Zeev Ben Zvi. V roce 1928, po studiích v Bezalel, odešel Ben Zvi studovat do Paříže. Po svém návratu působil krátce jako instruktor sochařství v Bezcalelu a v „Novém Becalelu“. V roce 1932 se konala jeho první výstava v muzeu národních starožitností Bezalel a o rok později uspořádal výstavu svých děl v Tel Avivském muzeu. Jeho socha „The Pioneer“ byla vystavena na veletrhu Orient v Tel Avivu v roce 1934. V díle Bena Zviho, stejně jako v Orloffově, jazyk kubistů, jazyk, ve kterém navrhoval své sochy, neopustil realismus a zůstal uvnitř hranice tradičního sochařství.[14]

Vliv francouzského realismu lze vidět také ve skupině izraelských umělců, kteří byli ovlivněni realistickým trendem francouzských sochařů počátku dvacátého století, jako Auguste Rodin, Aristide Maillol Symbolické zavazadlo jak jejich obsahu, tak jejich stylu se projevilo také v díle izraelských umělců, jako je Mojžíš Sternschuss, Raphael Chamizer, Moshe Ziffer, Joseph Constant (Constantinovsky) a Dov Feigin, z nichž většina studovala sochařství ve Francii.

Jedna z této skupiny umělců - Batya Lishanski - studovala malbu v Bezalel a absolvovala kurzy sochařství v pařížštině École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts. Když se vrátila do Izraele, vytvořila figurální a expresivní sochařství, které ukázalo jasný vliv Rodina, který zdůrazňoval tělesnost svých soch. Série památek, které vytvořil Lishanski, z nichž první byla „Práce a obrana“ (1929), která byla postavena nad hrobem Ephraim Chisik - který zahynul v bitvě o farmu Hulda (dnes Kibbutz Huldo ) - jako odraz sionistické utopie během tohoto období: kombinace vykoupení země a obrany vlasti.

Vliv německého umění a zejména německého expresionismu lze vidět ve skupině umělců, kteří do země Izrael přišli po absolvování uměleckého výcviku v různých německých městech a ve Vídni. Umělci jako Jacob Brandenburg, Trude Chaim, a Lili Gompretz-Beatus a George Leshnitzer vytvořili figurální plastiku, především portréty, navrženou ve stylu, který kolísal mezi impresionismem a umírněným expresionismem. Mezi umělci této skupiny Rudolf (Rudi) Lehmann, který začal učit umění ve studiu, které otevřel ve 30. letech 20. století, vyniká. Lehmann studoval sochařství a řezbářství u Němce jménem L. Feurdermeier, který se specializoval na sochy zvířat. Postavy, které Lehmann vytvořil, ukázaly vliv expresionismu v hrubém designu těla, který zdůrazňoval materiál, ze kterého byla socha vytvořena, a způsob, jakým sochař na ní pracoval. I přes celkové zhodnocení jeho práce byl Lehmann primárně důležitý jako učitel metod klasického sochařství v kameni a dřevě pro velké množství izraelských umělců.

Canaanite to abstract, 1939–1967

Na konci 30. let skupina nazvaná „Kanaánci „- v Izraeli bylo založeno široké sochařské hnutí, převážně literární povahy. Tato skupina se pokusila vytvořit přímou linii mezi ranými národy žijícími v zemi Izrael, ve druhém tisíciletí před křesťanskou dobou, a židovským lidem v země Izraele ve 20. století, zároveň usilovat o vytvoření nové staré kultury, která by se oddělila od židovské tradice. Umělcem, který byl s tímto pohybem nejtěsněji spojen, byl sochař Itzhak Danziger, který se vrátil do země Izrael v roce 1938 po studiu umění v Liberci Anglie. Nový nacionalismus, který navrhlo Danzigerovo „kanaanské“ umění, nacionalismus, který byl protievropský a plný východní smyslnosti a exotičnosti, odráží postoj mnoha lidí žijících v židovské komunitě v zemi Izrael. "Sen generace Danzigera", Amos Keinan napsal po Danzigerově smrti, bylo „spojit se se zemí Izraele a se zemí, vytvořit konkrétní obraz s rozeznatelnými znaky, něco, co je odtud a jsme my, a vtisknout známku toho něčeho zvláštního, co jsme my v historii .[15] Kromě nacionalismu vytvořili umělci sochařství, které vyjadřovalo symbolický expresionismus v duchu britského sochařství stejného období.

V Tel Avivu založil Danziger sochařské studio na dvoře nemocnice svého otce, kde kritizoval a učil mladé sochaře, jako např. Benjamin Tammuz, Kosso Eloul, Yehiel Shemi, Mordechai Gumpel, a další.[16] Kromě Danzigerových žáků se studio stalo místem setkávání umělců z jiných oborů. V tomto studiu vytvořil Danziger své první významné dílo - „Nimrod“ (1939) a „Šebazija“ (1939).

Od chvíle, kdy byla poprvé vystavena, se socha „Nimrod“ stala centrem sporu v kultuře Eretz Izraele; v této soše představil Danziger postavu Nimrod, biblický lovec, jako štíhlé mládí, nahý a neobřezaný, s mečem přitlačeným k tělu a sokolem na rameni. Forma sochy připomínala primitivní umění asyrské, egyptské a řecké kultury a v duchu se podobala evropskému sochařství tohoto období. Ve své podobě socha zobrazovala jedinečnou kombinaci homoerotický krása a uctívání pohanských idolů. Tato kombinace byla ve středu kritiky náboženské komunity v židovské osadě. Zároveň to ostatní hlasy prohlásily za model „nového židovského muže“. V roce 1942 se v novinách „HaBoker“ objevil článek, který prohlašuje, že „Nimrod není jen socha, je to tělo našeho těla, duch našeho ducha. Je to milník a památník. Je ztělesněním vynalézavosti a odvážnost, monumentalita, mladistvá vzpoura, která charakterizuje celou generaci ... Nimrod bude navždy mladý. “[17]

První představení sochy na "Všeobecné výstavě mladých lidí Eretze Izraele" v roce 2006 Divadlo Habima v květnu 1942[18] vyvolal přetrvávající spor o hnutí „Canaanite“. Kvůli výstavě Yonatan Ratosh, zakladatel hnutí, se s ním spojil a požádal o setkání s ním. Kritika proti „Nimrodovi“ a Kanaáncům nevycházela pouze z náboženských prvků, kteří, jak již bylo zmíněno výše, protestovali proti tomuto představiteli pohanů a modlářů, ale také ze strany světských kritiků, kteří odsoudili odstranění všeho „židovského“. „Nimrod“ do značné míry skončil uprostřed sporu, který byl zahájen dávno předtím.

Navzdory skutečnosti, že Danziger později vyjádřil pochybnosti o „Nimrodovi“ jako modelu pro izraelskou kulturu, přijalo mnoho dalších umělců kanaánský přístup k sochařství. Obrazy idolů a postav v „primitivním“ stylu se v izraelském umění objevovaly až do 70. let. Vliv této skupiny lze navíc do značné míry vidět v práci skupiny „New Horizons“, jejíž většina členů experimentovala s kanaánským stylem v rané fázi své umělecké kariéry.

Skupina „Nové obzory“

V roce 1948 vzniklo hnutíNové obzory Byl založen „(„ Ofakim Hadashim “). Identifikoval se s hodnotami evropské moderny, zejména s abstraktním uměním. Kosso Eloul, Moshe Sternschuss, a Dov Feigin byli jmenováni do skupiny zakladatelů hnutí a později se k nim přidali další sochaři. Izraelští sochaři byli vnímáni jako menšina nejen kvůli jejich malému počtu v hnutí, ale především kvůli dominanci malířského média z pohledu vůdců hnutí, zejména Joseph Zaritsky. Přestože většina soch členů skupiny nebyla „čistým“ abstraktním sochařstvím, obsahovala prvky abstraktního umění a metafyzickou symboliku. Non-abstraktní umění bylo vnímáno jako staromódní a irelevantní. Sternschuss například popsal tlak, který byl vyvíjen na členy skupiny, aby do svého umění nezahrnuli obrazové prvky. Byl to dlouhý boj, který začal v roce 1959, v roce, který byl členy skupiny považován za rok „vítězství abstrakce“[19] a svého vrcholu dosáhla v polovině 60. let. Sternschuss dokonce vyprávěl příběh o incidentu, ve kterém jeden z umělců chtěl vystavit sochu, která byla podstatně avantgardnější než to, co bylo obecně přijímáno. Ale mělo to hlavu, a proto jeden z členů správní rady proti němu v této záležitosti svědčil.[20]

Gideon Ophrat ve své eseji o skupině našel silné spojení mezi malbou a plastikou „New Horizons“ a uměním „Caananites“.[21] Navzdory „mezinárodnímu“ odstínu uměleckých forem, které členové skupiny vystavovali, řada jejich děl vykazovala mytologické zobrazení izraelské krajiny. Například v prosinci 1962 uspořádal Kosso Eloul v roce 2006 mezinárodní sympozium o sochařství Mitzpe Ramon. Tato událost sloužila jako příklad vzrůstajícího zájmu soch o izraelskou krajinu, zejména o pustou pouštní krajinu. Krajina byla na jedné straně vnímána jako základ myšlenkových procesů pro tvorbu mnoha pomníků a pamětních soch. Yona Fisher ve svém výzkumu umění v 60. letech spekuloval, že zájem sochařů o „kouzlo pouště“ nevznikl pouze z romantické touhy po přírodě, ale také ze snahy vštěpovat v Izraeli prostředí „kultury“, než „Civilizace“.[22]

Zkouška týkající se prací každého člena skupiny spočívala v odlišném způsobu, jakým se zabýval abstrakcí a krajinou. Krystalizace abstraktní povahy sochy Dov Feigina byla součástí procesu uměleckého hledání, které bylo ovlivněno mezinárodním sochařstvím, zejména Julio González, Constantin Brâncuși, a Alexander Calder. Nejvýznamnější umělecká změna nastala v roce 1956, kdy Feigin přešel k kovové (železné) plastice.[23] Jeho práce od letošního roku, jako „Bird“ a „Flight“, byly konstruovány svařením železných pásů, které byly umístěny do kompozic plných dynamiky a pohybu. Přechod od lineární plastiky k planární plastice pomocí řezané a ohýbané mědi nebo železa byl pro Feigina procesem přirozeného vývoje, který byl ovlivněn dílem Pablo Picasso provedeno podobnou technikou.

Na rozdíl od Feigina ukazuje Moshe Sternschuss postupnější vývoj v jeho pohybu k abstrakci. Po ukončení studia na Bezcale odešel Sternschuss studovat do Paříže. V roce 1934 se vrátil do Tel Avivu a byl jedním ze zakladatelů Avni Institute of Art and Design. Sternschussovy sochy během tohoto období vykazovaly akademický modernismus, ačkoli v nich postrádaly sionistické rysy přítomné v umění Becalelovy školy. Počínaje polovinou 40. let 20. století vykazovaly jeho lidské postavy výraznou tendenci k abstrakci a rostoucímu využívání geometrických forem. Jednou z prvních těchto soch byl „Tanec“ (1944), který byl v tomto roce vystaven na výstavě vedle „Nimrod“. Ve skutečnosti se Sternschussova práce nikdy nestala zcela abstraktní, ale nadále se zabývala lidskou postavou nefigurativními prostředky.[24]

Když se Itzhak Danziger v roce 1955 vrátil do Izraele, nastoupil do „New Horizons“ a začal vyrábět kovové sochy. Styl soch, které vytvořil, byl ovlivněn konstruktivistickým uměním, které bylo vyjádřeno v jeho abstraktních formách. Většina předmětů jeho soch však byla zjevně místní, jako u soch se jmény spojenými s Biblí, například „Hattinovy rohy“ (1956), místo Saladinova vítězství nad křižáky v roce 1187, nebo The Burning Bush (1957) nebo s místy v Izraeli, jako jsou „Ein Gedi“ (1950), „Sheep of the Negev“ (1963) atd. Do značné míry tato kombinace charakterizovala díla mnoha umělců hnutí.[25]

Yechiel Shemi, také jeden z Danzigerových žáků, se v roce 1955 z praktického důvodu přestěhoval do kovové sochy. Tento krok usnadnil přechod k abstrakci v jeho práci. Jeho práce, které využívaly techniku pájení, svařování a příklepu do tenkých pásů, byly jedním z prvních sochařů z této skupiny, kteří s těmito technikami pracovali.26 V pracích jako „Mythos“ (1956) Shemiho spojení s „Kanananitové“ umění, z něhož se vyvinul, lze stále vidět, ale brzy poté ze své práce odstranil všechny identifikovatelné znaky figurativního umění.

Narozený v Izraeli Ruth Tzarfati studovala sochařství v ateliéru Avni u Moses Sternschuss, který se stal jejím manželem. I přes stylistickou a společenskou blízkost Zarfati s umělci „New Horizons“ ukazuje její socha podtext, který je nezávislý na ostatních členech skupiny. To je vyjádřeno především v jejím zobrazení figurální plastiky se zakřivenými liniemi. Její socha „Sedí“ (1953) zobrazuje neidentifikovanou ženskou postavu s využitím liniových charakteristik evropského expresivního sochařství, jako je socha Henryho Moora. Další sochařská skupina „Baby Girl“ (1959) ukazuje skupinu dětí a kojenců navržených jako panenky v groteskních expresivních pózách.

David Palombo (1920 - 1966) realizoval před svou předčasnou smrtí řadu mocných abstraktních železných soch.[26] Palombovy sochy ze 60. let lze považovat za vyjádření vzpomínek holocaustu prostřednictvím „sochařské estetiky ohně“.[27]

Socha protestu

Na počátku 60. let se v izraelském umění začaly objevovat americké vlivy, zejména abstraktní expresionismus, pop-art a poněkud později konceptuální umění. Kromě nových uměleckých forem populární umění a konceptuální umění s sebou přineslo přímé spojení s politickou a sociální realitou té doby. Naproti tomu ústřední trend v izraelském umění směřoval k zaujetí osobním a uměleckým a do velké míry ignoroval diskusi o izraelské politické krajině. Umělci, kteří se zabývali sociálními nebo židovskými otázkami, byli považováni uměleckým zařízením za anarchisty.[28]

Jeden z prvních umělců, jehož díla vyjadřovala nejen mezinárodní umělecké vlivy, ale také tendenci řešit aktuální politické problémy, byla Yigal Tumarkin, který se do Izraele vrátil v roce 1961 na povzbuzení Yony Fischerové a Sama Dubinera z východního Berlína, kde byl vedoucím divadelní společnosti Berliner Ensemble pod vedením Bertholda Brechta.[29] Jeho rané sochy byly vytvořeny jako expresivní asambláže sestavené z částí různých druhů zbraní. Například jeho socha „Take Me Under Your Wings“ (1964–65) Tumarkin vytvořil jakýsi ocelový plášť, z něhož trčely hlavně pušek. Směs, kterou vidíme v této soše nacionalistické dimenze a lyrické, a dokonce erotické dimenze, se měla stát výrazným prvkem Tumarkinova politického umění v 70. letech.[30] Podobný přístup lze spatřit v jeho slavné soše „Kráčel v polích“ (1967) (stejného jména jako Moshe Shamir slavný příběh), který protestoval proti obrazu „mytologické Sabry“; Tumarkin mu svléká „kůži“ a odhaluje své roztrhané vnitřnosti, ze kterých vyčnívají zbraně a střelivo, a jeho žaludek, který obsahuje kulatou bombu, která vypadá podezřele jako děloha. Během 70. let se Tumarkinovo umění vyvinulo tak, aby zahrnovalo nové materiály ovlivněné „Land art „„ špína, větve stromů a kousky látky. Tímto způsobem se Tumarkin snažil zaostřit pozornost svého politického protestu proti tomu, co považoval za jednostranný přístup izraelské společnosti k arabsko-izraelskému konfliktu.

Po šestidenní válce začalo izraelské umění projevovat jiné protesty než Tumarkin. Zároveň tato díla nevypadala jako konvenční sochařská díla ze dřeva nebo kovu. Hlavním důvodem byl vliv různých druhů avantgardního umění, které se z velké části vyvinulo ve Spojených státech a ovlivnilo mladé izraelské umělce. Ducha tohoto vlivu lze spatřovat v tendenci k aktivním uměleckým dílům, které stírají hranice mezi různými oblastmi umění i oddělení umělce od společenského a politického života. Sochařství tohoto období již nebylo vnímáno jako samostatný umělecký objekt, nýbrž jako vrozené vyjádření fyzického a sociálního prostoru.

Krajinná socha v konceptuálním umění

Dalším aspektem těchto trendů byl rostoucí zájem o neomezenou izraelskou krajinu. Tyto práce byly ovlivněny Land Art a kombinace dialektického vztahu mezi „izraelskou“ krajinou a „východní“ krajinou. V mnoha pracích s rituálními a metafyzickými rysy lze vidět vývoj nebo přímý vliv kanaanských umělců nebo sochařů, spolu s abstrakcí „nových horizontů“, v různých vztazích s krajinou.

Jeden z prvních projektů v Izraeli pod hlavičkou konceptuálního umění provedla Joshua Neustein. V roce 1970 spolupracoval Neustein s Georgette Batlle a Gerry Marx o „Projektu řeky Jeruzaléma“. V rámci tohoto projektu reproduktory instalované přes pouštní údolí hrály smyčkové zvuky řeky ve východním Jeruzalémě na úpatí Abu Tor a klášter sv. Kláry a celou cestu až k Kidronské údolí. Tato imaginární řeka nejen vytvořila extrateritoriální muzejní atmosféru, ale také ironicky naznačila pocit mesiášského vykoupení po Šestidenní válce, v duchu Kniha Ezekiel (Kapitola 47) a Kniha Zachariáš (Kapitola 14).[31]

Jicchak Danziger, jehož práce začaly zobrazovat místní krajinu před několika lety, vyjádřil koncepční aspekt ve stylu, který vyvinul jako výraznou izraelskou variantu Land Art. Danziger cítil, že existuje potřeba smíření a zlepšení poškozeného vztahu mezi člověkem a jeho prostředím. Tato víra ho vedla k plánování projektů, které kombinovaly obnovu lokalit s ekologií a kulturou. V roce 1971 představil Danziger svůj projekt „Hanging Nature“ ve společném projektu The Izraelské muzeum. Práce byla složena ze závěsné látky, na které byla směs barev, plastové emulze, celulózových vláken a chemických hnojiv, na kterých Danziger pěstoval trávu pomocí systému umělého světla a zavlažování. Vedle látky byly promítány diapozitivy ukazující ničení přírody moderní industrializací. Výstava požadovala vytvoření ekologické jednoty, která by existovala současně jako „umění“ a jako „příroda“.[32] „Opravu“ krajiny jako umělecké události rozvinul Danziger ve svém projektu „Rehabilitace Nesherova lomu“ na severních svazích Mount Carmel. Tento projekt byl vytvořen jako spolupráce mezi Danziger, Zeev Naveh ekolog a Joseph Morin výzkumník půdy. V tomto projektu, který nebyl nikdy dokončen, se pokusili vytvořit pomocí různých technologických a ekologických prostředků nové prostředí mezi fragmenty kamene, které zůstaly v lomu. „Příroda by neměla být vrácena do svého přirozeného stavu,“ tvrdil Danziger. „Je třeba najít systém pro opětovné použití přírody, která byla vytvořena jako materiál pro zcela nový koncept.“[33] Po první fázi projektu byl pokus o rehabilitaci vystaven v roce 1972 na výstavě v Izraelském muzeu.

In 1973 Danziger began to collect material for a book that would document his work. Within the framework of the preparation for the book, he documented places of archaeological and contemporary ritual in Israel, places which had become the sources of inspiration for his work. Kniha, Makom (v hebrejština - místo), was published in 1982, after Danziger's death, and presented photographs of these places along with Danziger's sculptures, exercises in design, sketches of his works and ecological ideas, displayed as "sculpture" with the values of abstract art, such as collecting rainwater, etc. One of the places documented in the book is Bustan Hayat [could not confirm English spelling-sl ] at Nachal Siach in Haifa, which was built by Aziz Hayat in 1936. Within the framework of classes he gave at the Technion, Danziger conducted experiments in design with his students, involving them also with the care and upkeep of the Bustan.

In 1977 a planting ceremony was conducted in the Golanské výšiny for 350 Oak saplings, being planted as a memorial to the fallen soldiers of the Egoz Unit. Danziger, who was serving as a judge in "the competition for the planning and implementation of the memorial to the Northern Commando Unit," suggested that instead of a memorial sculpture, they put their emphasis on the landscape itself, and on a site that would be different from the usual memorial. ”We felt that any vertical structure, even the most impressive, could not compete with the mountain range itself. When we started climbing up to the site, we discovered that the rocks, that looked from a distance like texture, had a personality all of their own up close."[34] This perception derived from research in Bedouin and Palestinian ritual sites in the Land of Israel, sites in which the trees serve both as a symbol next to the graves of saints and as a ritual focus, "on which they hang colorful shiny blue and green fabrics from the oaks [...] People go out to hang these fabrics because of a spiritual need, they go out to make a wish."[35]

In 1972 group of young artists who were in touch with Danziger and influenced by his ideas created a group of activities that became known as "Metzer-Messer" in the area between Kibuc Metzer and the Arab village Meiser in the north west section of the Shomron. Micha Ullman, with the help of youth from both the kibbutz and the village, dug a hole in each of the communities and implemented an exchange of symbolic red soil between them. Moshe Gershuni called a meeting of the kibbutz members and handed out the soil of Kibbutz Metzer to them there, and Avital Geva created in the area between the two communities an improvised library of books recycled from Amnir Recycling Industries.[36]

Another artist influenced by Danziger's ideas was Yigal Tumarkin, who at the end of the 1970s, created a series of works entitled, "Definitions of Olive Trees and Oaks," in which he created temporary sculpture around trees. Like Danziger, Tumarkin also related in these works to the life forms of popular culture, particularly in Arab and Bedouin villages, and created from them a sort of artistic-morphological language, using "impoverished" bricolage methods. Some of the works related not only to coexistence and peace, but also to the larger Israeli political picture. In works such as "Earth Crucifixion" (1981) and "Bedouin Crucifixion" (1982), Tumarkin referred to the ejection of Palestinians and Bedouins from their lands, and created "crucifixion pillars" for these lands.[37]

Another group that operated in a similar spirit, while at the same time emphasizing Jewish metaphysics, was the group known as the "Leviathians," presided over by Avraham Ofek, Michail Grobman, and Shmuel Ackerman. The group combined conceptual art and "land art" with Jewish symbolism. Of the three of them, Avraham Ofek had the deepest interest in sculpture and its relationship to religious symbolism and images. In one series of his works Ofek used mirrors to project Hebrew letters, words with religious or cabbalistic significance, and other images onto soil or man-made structures. In his work "Letters of Light" (1979), for example, the letters were projected onto people and fabrics and the soil of the Judean Desert. In another work Ofek screened the words "America," "Africa," and "Green card" on the walls of the Tel Hai courtyard during a symposium on sculpture.[38]

Abstraktní sochařství

At the beginning of the 1960s Menashe Kadishman arrived on the scene of abstract sculpture while he was studying in Londýn. The artistic style he developed in those years was heavily influenced by English art of this period, such as the works of Anthony Caro, who was one of his teachers. At the same time his work was permeated by the relationship between landscape and ritual objects, like Danziger and other Israeli sculptors. During his stay in Europe, Kadishman created a number of totemic images of people, gates, and altars of a talismanic and primitive nature.[39] Some of these works, such as "Suspense" (1966), or "Uprise" (1967–1976), developed into pure geometric figures.

At the end of this decade, in works such as "Aqueduct" (1968–1970) or "Segments" (1969), Kadishman combined pieces of glass separating chunks of stone with a tension of form between the different parts of the sculpture. With his return to Israel at the beginning of the 1970s, Kadishman began to create works that were clearly in the spirit of "Land Art." One of his main projects was carried out in 1972. In the framework of this project Kadishman painted a square in yellow organic paint on the land of the Monastery of the Cross, in the Valley of the Cross at the foot of the Israel Museum. The work became known as a "monument of global nature, in which the landscape depicted by it is both the subject and the object of the creative process."[40]

Other Israeli artists also created abstract sculptures charged with symbolism. Sochy Michael Gross created an abstraction of the Israeli landscape, while those of Yaacov Agam contained a Jewish theological aspect. His work was also innovative in its attempt to create kinetické umění. Works of his such as "18 Degrees" (1971) not only eroded the boundary between the work and the viewer of the work but also exhorted the viewer to look at the work actively.

Symbolism of a different kind can be seen in the work of Dani Karavan. The outdoor sculptures that Karavan created, from "Památník Negevské brigády " (1963-1968) to "White Square" (1989) utilized avant-garde European art to create a symbolic abstraction of the Israeli landscape. In Karavan's use of the techniques of modernist, and primarily brutalist, architecture, as in his museum installations, Karavan created a sort of alternative environment to landscapes, redesigning it as a utopia, or as a call for a dialogue with these landscapes.[41]

Micha Ullman continued and developed the concept of nature and the structure of the excavations he carried out on systems of underground structures formulated according to a minimalist aesthetic. These structures, like the work "Third Watch" (1980), which are presented as defense trenches made of dirt, are also presented as the place which housed the beginning of permanent human existence.[42]

Buky Schwartz absorbed concepts from conceptual art, primarily of the American variety, during the period that he lived in New York City. Schwartz's work dealt with the way the relationship between the viewer and the work of art is constructed and deconstructed. V video umění film "Video Structures" (1978-1980) Schwartz demonstrated the dismantling of the geometric illusion using optical methods, that is, marking an illusory form in space and then dismantling this illusion when the human body is interposed.[43] In sculptures such as "Levitation" (1976) or "Reflection Triangle" (1980), Schwartz dismantled the serious geometry of his sculptures by inserting mirrors that produced the illusion that they were floating in the air, similarly to Kadishman's works in glass.

Representative sculpture of the 1970s

Performance began to develop in the Spojené státy in the 1960s, trickling into Israeli art towards the end of that decade under the auspices of the "Ten Plus " group, led by Raffi Lavie a „Třetí oko " group, under the leadership of Jacques Cathmore.[44] A large number of sculptors took advantage of the possibilities that the techniques of Performance Art opened for them with regard to a critical examination of the space around them. In spite of the fact that many works renounced the need for genuine physical expression, nevertheless the examination they carry out shows the clear way in which the artists related to physical space from the point of view of social, political, and gender issues.

Pinchas Cohen Gan during those years created a number of displays of a political nature. In his work "Touching the Border" (January 7, 1974) iron missiles, with Israeli demographic information written on them, were sent to Israel's border. The missiles were buried at the spot where the Israelis carrying them were arrested. In "Performance in a Refugees Camp in Jericho", which took place on February 10, 1974 in the northeast section of the city of Jericho near Khirbat al-Mafjar (Hisham's Palace), Cohen created a link between his personal experience as an immigrant and the experience of the Palestinian immigrant, by building a tent and a structure that looked like the sail of a boat, which was also made of fabric. At the same time, Cohen Gan set up a conversation about "Israel 25 Years Hence", in the year 2000, between two refugees, and accompanied by the declaration, "A refugee is a person who cannot return to his homeland."[45]

Další umělec, Efrat Natan, created a number of performances dealing with the dissolution of the connection between the viewer and the work of art, at the same time criticizing Israeli militarism after the Six Day War. Among her important works was "Head Sculpture," in which Natan consulted a sort of wooden sculpture which she wore as a kind of mask on her head. Natan wore the sculpture the day after the army's annual military parade in 1973, and walked with it to various central places in Tel Aviv. The form of the mask, in the shape of the letter "T," bore a resemblance to a cross or an airplane and restricted her field of vision."[46]

A blend of political and artistic criticism with poetics can be seen in a number of paintings and installations that Moshe Gershuni created in the 1970s. For Gershuni, who began to be famous during these years as a conceptual sculptor, art and the definition of esthetics was perceived as parallel and inseparable from politics in Israel. Thus, in his work "A Gentle Hand" (1975–1978), Gershuni juxtaposed a newspaper article describing abuse of a Palestinian with a famous love song by Zalman Shneur (called: "All Her Heart She Gave Him" and the first words of which are "A gentle hand", sung to an Arab melody from the days of the Second Aliyah (1904–1914). Gershuni sang like a muezzin into a loudspeaker placed on the roof of the Tel Aviv Museum. In works like these the minimalist and conceptualist ethics served as a tool for criticizing Zionism and Israeli society.[47]

Práce Gideon Gechtman during this period dealt with the complex relationship between art and the life of the artist, and with the dialectic between artistic representation and real life.[48] In the exhibition "Exposure" (1975), Gechtman described the ritual of shaving his body hair in preparation for heart surgery he had undergone, and used photographed documentation like doctors' letters and x-rays which showed the artificial heart valve implanted in his body. In other works, such as "Brushes" (1974–1975), he uses hair from his head and the heads of family members and attaches it to different kinds of brushes, which he exhibits in wooden boxes, as a kind of box of ruins (a reliquary). These boxes were created according to strict minimalistic esthetic standards.

Another major work of Gechtman's during this period was exhibited in the exhibition entitled "Open Workshop" (1975) at the Izraelské muzeum. The exhibition summarized the sociopolitical "activity" known as "Jewish Work" and, within this framework," Gechtman participated as a construction worker in the building of a new wing of the Museum and lived within the exhibition space. on the construction site. Gechtman also hung obituaries bearing the name "Jewish Work" and a photograph of the homes of Arab workers on the construction site. In spite of the clearly political aspects of this work, its complex relationship to the image of the artist in society is also evident.

80. a 90. léta

In the 1980s, influences from the international postmodern discourse began to trickle into Israeli art. Particularly important was the influence of philosophers such as Jacques Derrida and Jean Baudrillard, who formulated the concept of the semantic and relative nature of reality in their philosophical writings. The idea that the artistic representation is composed of "simulacra", objects in which the internal relation between the signifier and the signified is not direct, created a feeling that the status of the artistic object in general, and of sculpture in particular, was being undermined.

Gideon Gechtman's work expresses the transition from the conceptual approach of the 1970s to the 1980s, when new strategies were adopted that took real objects (death notices, a hospital, a child's wagon) and gradually converted them into objects of art.[49] The real objects were recreated in various artificial materials. Death notices, for example, were made out of colored neon lights, like those used in advertisements. Other materials Gechtman used in this period were formica and imitation marble, which in themselves emphasized the artificiality of the artistic representation and its non-biographical nature.

Painting Lesson, no 5, 1986

Acrylic and industrial paint on wood; nalezený objekt

Izraelské muzeum sbírka

During the 1980s, the works of a number of sculptors were known for their use of plywood. The use of this material served to emphasize the way large-scale objects were constructed, often within the tradition of do-it-yourself carpentry. The concept behind this kind of sculpture emphasized the non-heroic nature of a work of art, related to the "Arte Povera" style, which was at the height of its influence during these years. Among the most conspicuous of the artists who first used these methods is Nahum Tevet, who began his career in the 1970s as a sculptor in the minimalist and conceptual style. While in the early 1970s he used a severe, nearly monastic, style in his works, from the beginning of the 1980s he began to construct works that were more and more complex, composed of disassembled parts, built in home-based workshops. The works are described as "a trap configuration, which seduces the eye into penetrating the content [...] but is revealed as a false temptation that blocks the way rather than leading somewhere."[50] The group of sculptors who called themselves "Drawing Lessons," from the middle of the decade, and other works, such as "Ursa Major (with eclipse)" (1984) and "Jemmain" (1986) created a variety of points of view, disorder, and spatial disorientation, which "demonstrate the subject's loss of stability in the postmodernist world."[51]

Sochy Drora Domini as well dealt with the construction and deconstruction of structures with a domestic connection. Many of them featured disassembled images of furniture. The abstract structures she built, on a relatively small scale, contained absurd connections between them. Towards the end of the decade Domini began to combine additional images in her works from compositions in the "ars poetica" style.[52]

Another artist who created wooden structures was the sculptor Isaac Golombek. His works from the end of the decade included familiar objects reconstructed from plywood and with their natural proportions distorted. The items he produced had structures one on top of another. Itamar Levy, in his article "High Low Profile" [Rosh katan godol],[53] describes the relationship between the viewer and Golombek's works as an experiment in the separation of the sense of sight from the senses of touching and feeling. The bodies that Golombek describes are dismantled bodies, conducting a protest dialogue against the gaze of the viewer, who aspires to determine one unique, protected, and explainable identity for the work of art. While the form of the object represents a clear identity, the way they are made distances the usefulness of the objects and disrupts the feeling of materiality of the items.

A different kind of construction can be seen in the performances of the Zik Group, which came into being in the middle of the 1980s. Within the framework of its performances, the Group built large-scale wooden sculptures and created ritualistic activities around them, combining a variety of artistic techniques. When the performance ended, they set fire to the sculpture in a public burning ceremony. In the 1990s, in addition to destruction, the group also took began to focus on the transformation of materials and did away with the public burning ceremonies.[54]

Postmodern trends

Another effect of the postmodern approach was the protest against historical and cultural narratives. Art was not yet perceived as ideology, supporting or opposing the discourse on Israeli hegemony, but rather as the basis for a more open and pluralistic discussion of reality. In the era following the "political revolution" which resulted from the 1977 election, this was expressed in the establishment of the "identity discussion," in which parts of society that up to now had not usually been represented in the main Israeli discourse were included.

In the beginning of the 1980s expressions of the trauma of the Holocaust began to appear in Israeli society. In the works of the "second generation" there began to appear figures taken from druhá světová válka, combined with an attempt to establish a personal identity as an Israeli and as a Jew. Among the pioneering works were Moshe Gershuni 's installation "Red Sealing/Theatre" (1980) and the works of Haim Maor. These expressions became more and more explicit in the 1990s. A large group of works was created by Igael Tumarkin, who combined in his monumental creations dialectical images representing the horrors of the Holocaust with the world of European culture in which it occurred. Umělec Penny Yassour, for example, represented the Holocaust in a series of structures and models in which hints and quotes referring to the war appear. In the work "Screens" (1996), which was displayed at the "Documenta" exhibition, Yassour created a map of German trains in 1938 in the form of a table made out of rubber, as part of an experiment to present the memory and describe the relationship between private and public memory.[55] The other materials Yassour used – metal and wood that created different architectonic spaces – produced an atmosphere of isolation and horror.

Another aspect of raising the memory of the Holocaust to the public consciousness was the focus on the immigrants who came to Israel during the first decades after the founding of the State. These attempts were accompanied by a protest against the image of the Israeli "Sabra " and an emphasis on the feeling of detachment of the immigrants. The sculptor Philip Rentzer presented, in a number of works and installations, the image of the immigrant and the refugee in Israel. His works, constructed from an assemblage of various ready-made materials, show the contrast between the permanence of the domestic and the feeling of impermanence of the immigrant. In his installation "The Box from Nes Ziona" (1998), Rentzer created an Orientalist camel carrying on its back the immigrants' shack of Rentzer's family, represented by skeletons carrying ladders.[56]

In addition to expressions of the Holocaust, a growing expression of the motifs of Jewish art can be seen in Israeli art of the 1990s. In spite of the fact that motifs of this kind could be seen in the past in art of such artists as Arie Aroch, Moshe Castel, a Mordechai Ardon, the works of Israeli artists of the 1990s displayed a more direct relationship to the world of Jewish symbols. One of the most visible of the artists who used these motifs, Belu Simion Fainaru used Hebrew letters and other symbols as the basis for the creation of objects with metaphysical-religious significance. In his work "Sham" ("There" in Hebrew) (1996), for example, Fainaru created a closed structure, with windows in the form of the Hebrew letter Holeň (ש). In another work, he made a model of a synagogue (1997), with windows in the shape of the letters, Aleph (א) to Zayin (ז) - one to seven - representing the seven days of the creation of the world.[57]

During the 1990s we also begin to see various representations of Rod and sexual motifs. Sigal Primor exhibited works that dealt with the image of women in Western culture. In an environmental sculpture she placed on Sderot Chen in Tel Aviv-Jaffa, Primor created a replica of furniture made of stainless steel. In this way, the structure points out the gap between personal, private space and public space. In many of Primor's works there is an ironic relationship to the motif of the "bride", as seen Marcel Duchamp's work, "The Glass Door". In her work "The Bride", materials such as cast iron, combined with images using other techniques such as photography, become objects of desire.

In her installation "Dinner Dress (Tales About Dora)" (1997), Tamar Raban turned a dining room table four meters in diameter into a huge crinoline and she organized an installation that took place both on top of and under the dining room table. The public was invited to participate in the meal prepared by chef Tsachi Bukshester and watch what was going on under the table on monitors placed under the transparent glass dinner plates.[58] The installation raises questions about the perceptions of memory and personal identity in a variety of ways. During the performance, Raban would tell stories about "Dora," Raban's mother 's name, with reference to the figure "Dora" – a nickname for Ida Bauer, one of the historic patients of Sigmund Freud. In the corner of the room was the artist Pnina Reichman, embroidering words and letters in English, such as "all those lost words" and "contaminated memory," and counting in jidiš.[59]

The centrality of the gender discussion in the international cultural and art scene had an influence on Israeli artists. In the video art works of Hila Lulu Lin, the protest against the traditional concepts of women's sexuality stood out. In her work "No More Tears" (1994), Lulu Lin appeared passing an egg yolk back and forth between her hand and her mouth. Other artists sought not only to express in their art homoeroticism and feelings of horror and death, but also to test the social legitimacy of homosexuality and lesbianism in Israel. Among these artists the creative team of Nir Nader a Erez Harodi, and the performance artist Dan Zakheim vyčnívat.

As the world of Israeli art was exposed to the art of the rest of the world, especially from the 1990s, a striving toward the "total visual experience,"[60] expressed in large-scale installations and in the use of theatrical technologies, particularly of video art, can be seen in the works of many Israeli artists. The subject of many of these installations is a critical test of space. Among these artists can be found Ohad Meromi a Michal Rovner, who creates video installations in which human activities are converted into ornamental designs of texts. V pracích Uri Tzaig the use of video to test the activity of the viewer as a critical activity stands out. In "Universal Square" (2006), for example, Tzaig created a video art film in which two football teams compete on a field with two balls. The change in the regular rules created a variety of opportunities for the players to come up with new plays on the space of the football field.

Another well-known artist who creates large-scale installations is Sigalit Landau. Landau creates expressive environments with multiple sculptures laden with political and social allegorical significance. The apocalyptic exhibitions Landau mounted, such as "The Country" (2002) or "Endless Solution" (2005), succeeded in reaching large and varied segments of the population.

Commemorative sculpture

In Israel there are many memorial sculptures whose purpose is to perpetuate the memory of various events in the history of the Jewish people and the State of Israel. Since the memorial sculptures are displayed in public spaces, they tend to serve as an expression of popular art of the period. The first memorial sculpture erected in the Land of Israel was “The Roaring Lion”, which Abraham Melnikoff sculpted in Tel Hai. The large proportions of the statue and the public funding that Melnikoff recruited towards its construction, was an innovation for the small Israeli art scene. From a sculptural standpoint, the statue was connected to the beginnings of the “Caananite” movement in art.

The memorial sculptures erected in Israel up to the beginning of the 1950s, most of which were memorials for the fallen soldiers of the War of Independence, were characterized for the most part by their figurative subjects and elegiac overtones, which were aimed at the emotions of the Zionist Israeli public.[61] The structure of the memorials was designed as spatial theater. The accepted model for the memorial included a wall with a wall covered in stone or marble, the back of which remained unused. On it, the names of the fallen soldiers were engraved. Alongside this was a relief of a wounded soldier or an allegorical description, such as descriptions of lions. A number of memorial sculptures were erected as the central structure on a ceremonial surface meant to be viewed from all sides.[62]

In the design of these memorial sculptures we can see significant differences among the accepted patterns of memory of that period. Hašomer Hatzair (The Youth Guard) kibbutzim, for example, erected heroic memorial sculptures, such as the sculptures erected on Kibbutz Jad Mordechai (1951) or Kibbutz Negba (1953), which were expressionist attempts to emphasize the ideological and social connections between art and the presence of public expression. V rámci HaKibbutz Ha’Artzi intimate memorial sculptures were erected, such as the memorial sculpture “Mother and Child”, which Chana Orloff erected at Kibbutz Ein Gev (1954) nebo Yechiel Shemi's sculpture on Kibbutz Hasolelim (1954). These sculptures emphasized the private world of the individual and tended toward the abstract.[63]

One of the most famous memorial sculptors during the first decades after the founding of the State of Israel was Nathan Rapoport, who immigrated to Israel in 1950, after he had already erected a memorial sculpture in the Varšavské ghetto to the fighters of the Ghetto (1946–1948). Rapoport's many memorial sculptures, erected as memorials on government sites and on sites connected to the War of Independence, were representatives of sculptural expressionism, which took its inspiration from Neoclassicism as well. At Warsaw Ghetto Square at Yad Vashem (1971), Rapoport created a relief entitled “The Last March”, which depicts a group of Jews holding a Torah scroll. To the left of this, Rapoport erected a copy of the sculpture he created for the Warsaw Ghetto. In this way, a “Zionist narrative” of the Holocaust was created, emphasizing the heroism of the victims alongside the mourning.

In contrast to the figurative art which had characterized it earlier, from the 1950s on a growing tendency towards abstraction began to appear in memorial sculpture. At the center of the “Pilots’ Memorial" (1950s), erected by Benjamin Tammuz a Aba Elhanani in the Independence Park in Tel Aviv-Yafo, stands an image of a bird flying above a Tel Aviv seaside cliff. The tendency toward the abstract can also be seen the work by David Palombo, who created reliefs and memorial sculptures for government institutions like the Knesset and Yad Vashem, and in many other works, such as the memorial to Shlomo Ben-Yosef že Itzhak Danziger postaven v Rosh Pina. However, the epitome of this trend toward avoidance of figurative images stands our starkly in the “Monument to the Negev Brigade” (1963–1968) which Dani Karavan created on the outskirts of the city of Beersheva. The monument was planned as a structure made of exposed concrete occasionally adorned with elements of metaphorical significance. The structure was an attempt to create a physical connection between itself and the desert landscape in which it stands, a connection conceptualized in the way the visitor wanders and views the landscape from within the structure. A mixture of symbolism and abstraction can be found in the “Monument to the Holocaust and National Revival”, erected in Tel Aviv's Rabinovo náměstí (then “Kings of Israel Square”). Igael Tumarkin, creator of the sculpture, used elements that created the symbolic form of an inverted pyramid made of metal, concrete, and glass. In spite of the fact that the glass is supposed to reflect what is happening in this urban space,[64] the monument didn't express the desire for the creation of a new space which would carry on a dialogue with the landscape of the “Land of Israel”. The pyramid sits on a triangular base, painted yellow, reminiscent of the “Mark of Cain”. The two structures together form a Magen David. Tumarkin saw in this form “a prison cell that has been opened and breached. An overturned pyramid, which contains within itself, imprisoned in its base, the confined and the burdensome.”[65] The form of the pyramid shows up in another work of the artists as well. In a late interview with him, Tumarkin confided that the pyramid can be perceived also as the gap between ideology and its enslaved results: “What have we learned since the great pyramids were built 4200 years ago?[...] Do works of forced labor and death liberate?”[66]

In the 1990s memorial sculptures began to be built in a theatrical style, abandoning the abstract. In the “Children’s Memorial” (1987), or the “Yad Vashem Train Car” (1990) by Moshe Safdie, or in the Memorial to the victims of “The Israeli Helicopter Disaster” (2008), alongside the use of symbolic forms, we see the trend towards the use of various techniques to intensify the emotional experience of the viewer.

Vlastnosti

Attitudes toward the realistic depiction of the human body are complex. The birth of Israeli sculpture took place concurrently with the flowering of avantgarde and modernist European art, whose influence on sculpture from the 1930s to the present day is significant. In the 1940s the trend toward primitivism among local artists was dominant. With the appearance of “Canaanite” art we see an expression of the opposite concept of the human body, as part of the image of the landscape of “The Land of Israel.” That same desolate desert landscape became a central motif in many works of art until the 1980s. With regard to materials, we see a small amount of use of stone and marble in traditional techniques of excavation and carving, and a preference for casting and welding. This phenomenon was dominant primarily in the 1950s, as a result of the popularity of the abstract sculpture of the “New Horizons” group. In addition, this sculpture enabled artists to create art on a monumental scale, which was not common in Israeli art until then.

Viz také

Reference

- ^ See, Yona Fischer (Ed.), Art and Art in the Land of Israel in the Nineteenth Century (Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, 1979). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Gideon Ofrat, Sources of the Land of Israel Sculpture, 1906-1939 (Herzliya: Herzliya Museum, 1990). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ See, Gideon Efrat, The New Bezalel, 1935-1955 (Jerusalem: Bezalel Academy of Art and Design, 1987) pp. 128-130. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ See, Alec Mishory, Behold, Gaze, and See (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2000) pp. 53–55. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ ] See, Alec Mishory, Behold, Gaze, and See (Tel Aviv: Am Oved, 2000) p. 51. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Nurit Shilo-Cohen, Schatz’s Bezalel (Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, 1983) pp. 55–68. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ ] Nurit Shilo-Cohen, Schatz’s Bezalel (Jerusalem, The Israel Museum, 1983) p.98. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ About the jewelry design of Raban, see Yael Gilat, “The Ben Shemen Jewelers’ Community, Pioneer in the Work-at-Home Industry: From the Resurrection of the Spirit of the Botega to the Resurrection of the Guilds,” in Art and Crafts, Linkages, and Borders, edited by Nurit Canaan Kedar, (Tel Aviv: The Yolanda and David Katz Art Faculty, Tel Aviv University, 2003), 127–144. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Haim Gamzo compared the sculpture to the image of the Assyrian lion from Khorsabad, found in the collection of the Louvre. See Haim Gamzo, The Art of Sculpture in Israel (Tel Aviv: Mikhlol Publishing House Ltd., 1946) (without page numbers). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ see: Yael Gilat, Artists Write the Myth Again: Alexander Zaid’s Memorial and the Works That Followed in its Footsteps, Oranim Academic College Website [In Hebrew] <http://info.oranim.ac.il/home/home.exe/16737/23928?load=T.htm Archivováno 2007-09-28 na Wayback Machine >

- ^ Yael Gilat, Artists Write the Myth Again: Alexander Zaid’s Memorial and the Works That Followed in its Footsteps, Oranim Academic College Website [In Hebrew]

- ^ See Haim Gamzo, Chana Orloff (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1968). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ ] Her museum exhibitions during those years took place in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art in 1935, and in the Tel Aviv Museum of Art and the Haifa Museum of Art in 1949.

- ^ Haim Gamzo, The Sculptor Ben-Zvi (Tel Aviv: HaZvi Publications, 1955). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Amos Kenan, “Greater Israel,” Yedioth Ahronoth, 19 August 1977. [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] The Story of Israeli Art, Benjamin Tammuz, Editor (Jerusalem: Masada Publishing House, 1980), p. 134. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Cited in: Sara Breitberg Semel, “Agripas vs. Nimrod,” Kav, No. 9 (1999). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ ] This exhibition is dated according to Gamzo’s critique, which was published on May 2, 1944.

- ^ Yona Fischer and Tamar Manor-Friedman, The Birth of Now (Ashdod: Ashdod Museum of Art, 2008), p. 10. [In Hebrew]

- ^ On the subject of kibbutz pressure, see Gila Blass, New Horizons (Tel Aviv: Papyrus and Reshefim Publishers, 1980), pp. 59–60. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ See Gideon Ophrat, “The Secret Canaanism in ‘New Horizons’,” Art Visits [Bikurei omanut], 2005.

- ^ ] Yona Fischer and Tamar Manor-Friedman, The Birth of Now (Ashdod: Ashdod Museum of Art, 2008), pp. 30–31. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ See: L. Orgad, Dov Feigin (Tel Aviv: The Kibbutz HaMeuhad [The United Kibbutz], 1988), pp. 17–19. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ See: Irit Hadar, Moses Sternschuss (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 2001). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ ] A similar analysis of the narrative of Israeli sculpture appears in Gideon Ophrat’s article, “The Secret Canaanism” in ‘New Horizons’,” Studio, No. 2 (August, 1989). [In Hebrew] The article appears also in his book, With Their Backs to the Sea: Images of Place in Israeli Art and Literature, Israeli Art (Israeli Art Publishing House, 1990), pp. 322–330.

- ^ David Palombo, na Knesset website, accessed 16 October 2019

- ^ Gideon Ofrat. "Aharon Bezalel". Aharon Bezalel sculptures. Citováno 16. října 2019.

Indeed, the sculptural aesthetics of fire, bearing memories of the Holocaust (at that time finding their principal expression in the sculptures of Palombo)....

- ^ See: Yona Fischer and Tamar Manor-Friedman, The Birth of Now (Ashdod: Ashdod Museum of Art, 2008), p. 76. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Igael Tumarkin, “Danziger in the Eyes of Igael Tumarkin,” Studio, No. 76 (October–November 1996), pp. 21–23. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Ginton, Allen, The Eyes of the Country: Visual Arts in a Country Without Borders (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1998), p. 28. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Ginton, Allen, The Eyes of the Country: Visual Arts in a Country Without Borders (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1998), pp. 32–36. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Yona Fischer , in: Itzhak Danziger, Place (Tel Aviv: Ha Kibbutz HaMeuhad Publishing House, 1982. (The article is untitled and preceded by the following quotation: “Art precedes science.” The pages in the book are unnumbered). [In Hebrew]

- ^ From "Rehabilitation of the Nesher Quarry, Israel Museum, 1972, " in: Yona Fischer, in Itzhak Danziger, Place (Tel Aviv: Ha Kibbutz HaMeuhad Publishing House, 1982. [In Hebrew]

- ^ Itzhak Danziger, The Project for the Memorial to the Fallen Soldiers of the Egoz Commando Unit. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ ] Amnon Barzel, “Landscape as an Artistic Creation” (Interview with Itzhak Danziger), Haaretz (July 27, 1977). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ See: Ginton Allen, The Eyes of the Country: Visual Arts in a Country Without Borders (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1998), pp. 88–89. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Yigal Zalmona, Onward: The East in Israeli Art (Jerusalem: The Israel Museum, 1998), pp. 82–83. For documentation of much of Danziger’s sculptural activity, see Igael Tumarkin, Trees, Stones, and Fabrics in the Wind (Tel Aviv: Masada Publishing House, 1981. [In Hebrew]

- ^ ] See: The Story of Israeli Art, Benjamin Tammuz, Editor (Jerusalem: Masada Publishing House, 1980), pp. 238–240. Also Gideon Efrat, Abraham Ofek House (Kibbutz Ein Harod, Haim Atar Museum of Art, 1986), primarily pp. 136–148. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ ] Pierre Restany, Kadishman (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1996), pp. 43-48. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Pierre Restany, Kadishman (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1996), p. 127. [In Hebrew]

- ^ See: Ruti Director, “When Politics Becomes Kitsch,” Studio, no. 92 (April 1998), pp. 28–33.

- ^ See: Amnon Barzel, Israel: The 1980 Biennale (Jerusalem: Ministry of Education, 1980). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ See: Video Zero: Written on the Body – A Live Transmission, the Screened Image – the First Decade, edited by Ilana Tannenbaum (Haifa: Haifa Museum of Art, 2006), p. 48, pp. 70–71. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ See: Video Zero: Written on the Body -- A Live Transmission, the Screened Image – the First Decade, edited by Ilana Tannenbaum (Haifa: Haifa Museum of Art, 2006) pp. 35–36. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ See: Jonathan Allen, The Eyes of the Country: Visual Arts in a Country Without Borders (Tel Aviv: Tel Aviv Museum of Art, 1998), pp. 142–151. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Viz: Video Zero: Written on the Body - A Live Transmission, the Screened Image - the First Decade, edited by Ilana Tannenbaum (Haifa: Haifa Museum of Art, 2006), str. 43. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Viz: Irit Segoli, „My Red is Your Dear Blood“, Studio, č. 76 (říjen – listopad 1996), str. 38–39. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Viz: Gideon Efrat, „The Heart of the Matter“, Gideon Gechtman: Works 1971-1986, podzim 1986, nečíslováno. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Viz: Neta Gal-Atzmon, „Cykly originálu a imitace: Práce 1973–2003“, Gideon Gechtman, Hedva, Gideon a Všichni ostatní (Tel Aviv: Sdružení malířů a sochařů) (složka Unsumbered looseleaf). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Sarit Shapira, Jedna věc po druhé (Jeruzalém: Izraelské muzeum, 2007), s. 21. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Viz: Nahum Tevet na výstavě „Check-Post“ (Web of the Haifa Museum of Art).

- ^ Viz: Drora Dumani na výstavě „Check-Post“ (Web muzea umění v Haifě).

- ^ Viz: Itamar Levy, „High Low Profile“, Studio: Journal of Art, č. 111 (únor 2000), str. 38–45. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ The Zik Group: Twenty Years of Work, edited by Daphna Ben-Shaul (Jerusalem: Keter Publishing House, 2005). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ ] Viz: Galia Bar Nebo „Parodoxical Space“, Studio, č. 109 (listopad – prosinec 1999), s. 45–53. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Viz: „Přistěhovalec s nátlakem“, webové stránky Ynet: http://www.ynet.co.il/articles/0,7340,L-3476177,00.html [V hebrejštině]

- ^ David Schwarber, Ifcha Mistabra: Kultura chrámu a současné izraelské umění (Ramat Gan: Bar Ilan University), s. 46–47. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Dokumentaci k instalaci najdete v části „Večerní šaty“ a související video na YouTube.

- ^ Viz: Levia Stern, „Conversations About Dora“, Studio: Journal of Art, No. 91 (březen 1998), s. 34–37. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Amitai Mendelson, „Otevírací a uzavírací brýle: Rumblings o umění v Izraeli, 1998-2007,“ v reálném čase (Jeruzalém: Izraelské muzeum, 2008). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Viz: Gideon Efrat, „The Dialectic of the 1950: Hegemony and Multiciplicity,“ in: Gideon Efrat and Galia Bar Or, The First Decade: Hegemony and Multiciplicity (Kibbutz Ein Harod, Haim Atar Museum of Art, 2008), str. 18. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Viz: Avner Ben-Amos, „Divadlo paměti a smrti: Památníky a obřady v Izraeli“, Drora Dumani, Všude: Izraelská krajina s památníkem (Tel Aviv: Hargol, 2002). [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Viz: Galia Bar Nebo „Universal and International: The Art of the Kibbutz in the First Decade“, v Gideon Efrat a Galia Bar Or, The First Decade: Hegemony and Multiciplicity (Kibbutz Ein Harod, Muzeum umění Haim Atar, 2008) , str. 88. [V hebrejštině]

- ^ Yigal Tumarkin, „Památník holocaustu a obrození“, v Tumarkinu (Tel Aviv: Nakladatelství Masada, 1991 (nečíslované stránky)

- ^ ] Yigal Tumarkin, „Památník holocaustu a obrození“, v Tumarkinu (Tel Aviv: Nakladatelství Masada, 1991 (nečíslované stránky)

- ^ Michal K. Marcus, V prostorné době Yigala Tumarkina.