Nair - Nair

Nair podle Thomas Daniell. Kreslen tužkou a akvarelem někdy mezi 17. a 18. stoletím. | |

| Regiony s významnou populací | |

|---|---|

| Kerala | |

| Jazyky | |

| Malayalam,[1] Sanskrt[1] | |

| Náboženství | |

| hinduismus |

The Nair /ˈnaɪər/, také známý jako Nayar, jsou skupina indický Hind kasty, popsal antropolog Kathleen Gough jako „ne jednotná skupina, ale pojmenovaná kategorie kast“. Nair zahrnuje několik kast a mnoho dalších útvarů, z nichž ne všechny historicky nesly jméno „Nair“.[2][3] Tito lidé žili a nadále žijí v oblasti, která je nyní indickým státem Kerala. Jejich vnitřní kasta chování a systémy se mezi obyvateli v severní a jižní části oblasti výrazně liší, i když o těch, kteří obývají sever, není příliš spolehlivých informací.[4]

Historicky Nairs žil ve velkých rodinných jednotkách tharavads že bydleli potomci jedné společné předky ženy. Tyto rodinné jednotky spolu s jejich neobvyklými zvyky v manželství, které se již nepraktikují, byly hodně studovány. Ačkoli se podrobnosti v jednotlivých regionech lišily, výzkumníky nairských manželských zvyků zajímaly hlavně dva zvláštní rituály - předpubertální thalikettu kalyanam a později sambandam —A praxe mnohoženství v některých oblastech. Některé nairské ženy také cvičily hypergamie s Nambudiri Brahminové z Malabarská oblast.

Nair byli historicky zapojeni do vojenských konfliktů v regionu. Po nepřátelských akcích mezi Nairem a Brity v roce 1809 omezili Britové účast Nairů v Britská indická armáda. Po Nezávislost Indie, Brigáda Nair z Travancore Státní síly byly sloučeny do Indická armáda a stal se součástí 9. prapor, regiment Madras, nejstarší prapor v indické armádě.

The had je uctíván rodinami Nairů jako strážce klanu. The uctívání hadů, a Dravidian Zvyk,[5] je v této oblasti tak převládající antropolog poznámky: „V žádné části světa není uctívání hadů obecnější než v Kérale.“[6] Hadí háje byly nalezeny v jihozápadním rohu téměř každé Nairovy sloučeniny.[7]

Dějiny

Počáteční období

Původ Nair je sporný. Někteří lidé si myslí, že samotný název je odvozen nayaka, čestný význam „vůdce lidu“, zatímco jiní věří, že to vychází ze sdružení komunity s Naga kult hadího uctívání.[8] Christopher Fuller, antropolog, uvedl, že je pravděpodobné, že první zmínka o komunitě Nair byla učiněna Plinius starší v jeho Přírodní historie, z roku 77 n. l. Tato práce popisuje pravděpodobně pobřežní oblast Malabaru, kde lze nalézt „Nareae, které uzavírají pohoří Capitalis, nejvyšší ze všech hor v Indii“. Fuller věří, že je pravděpodobné, že Nareae uvedený na Nairs a rozsah Capitalis je Západní Ghats.[9]

Ve známé rané historii regionu Kerala existují velké mezery, o nichž se předpokládá, že v 1. století našeho letopočtu byly řízeny Dynastie Chera a které se na konci 3. století našeho letopočtu rozpadly, pravděpodobně v důsledku poklesu obchodu s Římané. V tomto období neexistují žádné důkazy o Nairech v této oblasti. Nápisy na měděném štítku týkající se udělování pozemků a práv na osady židovských a křesťanských obchodníků, datované přibližně mezi 7. a 9. stoletím našeho letopočtu, odkazují na nairské náčelníky a vojáky Ernada Valluvanad, Venad (později známý jako Travancore ) a Palghat oblastech. Protože tyto nápisy ukazují Nairs jako svědky dohod mezi těmito obchodníky a následníky Cheras, Perumals, je pravděpodobné, že do této doby byli Naíři vazalský náčelníci.[12]

Určitě do 13. století byli někteří Naíři vládci malých království a Perumals zmizeli. Obchod s Čínou, který na nějakou dobu poklesl, se ve 13. století začal znovu zvyšovat a během tohoto období byla založena dvě malá království Nair. Oba - v Kolattunad a na Vernadu - obsahovaly hlavní námořní přístavy a rozšiřovaly se převzetím vnitrozemského území sousedních náčelníků. Ačkoli obchod s Čínou ve 14. století opět upadl, byl nahrazen obchodem s muslimskými Araby. Tito obchodníci tuto oblast navštěvovali již několik set let, ale jejich aktivity vzrostly natolik, že třetí království Nair založené na přístavu Calicut se ustálilo. Tam byla také malá království na Walluvanad a Palghat, daleko od pobřeží.[13] Toto období bylo charakterizováno nepřetržitou válkou mezi těmito různými královstvími a nejschopnější Nair muži byli přiděleni k boji v těchto válkách. [11]

Velký příliv cestujících a obchodníků do Keraly zanechal mnoho raných účtů Nairů. Tyto popisy byly původně Evropany idealizovány pro její bojovou společnost, produktivitu, duchovnost a pro její manželské praktiky. Některé rané příklady těchto děl John Mandeville „Travels“ (1356), „Mirrour of the Wourld“ od Williama Saxtona (1481) a Jean Boudin „Les sex livres de la republque“ (1576). [14] Nairští muži jsou ve starých zdrojích popisováni jako zdvořilí a dobře vychovaní,[15] a téměř všechny historické popisy je popisují jako arogantní.[16][15] Zdroje o Nairských ženách jsou skromné a byly napsány muži, přičemž tyto komentují především jejich krásu.[16][15] Bojová společnost Nairů byla něco, co pokrývali téměř všichni návštěvníci, a jejich charakteristika vždy ozbrojeného je dobře popsána.[17]

The portugalština dorazil do oblasti od roku 1498, do té doby Zamorin (Král) z Calicutu se dostal do popředí. Arabští obchodníci se pevně usadili v jeho přístavu, a přestože obchod stále směřoval do přístavů dalších dvou malých království, bylo to v relativně malém množství. Království založené na Kolattunadu se skutečně rozpadlo na tři ještě menší království; a vládce Vernadu připustil značné pravomoci místním náčelníkům v jeho království.[18] V době evropského příjezdu byl název Nair používán k označení všech vojenských kast. Portugalci používali termín Nair pro všechny vojáky a před rokem 1498 se věřilo, že se vojákům nebo zadržovacím Nairům říkalo „Lokar“. Gough uvádí, že název Nair existoval před tím časem a odkazoval se pouze na ty rodiny, které byly zapojeny do armády.[2][A]Portugalci se v jižní Indii hodně angažovali, včetně podpory Indie Paravars v obchodní bitvě o kontrolu nad lovem perel Malabar, ale v království Nair bylo jejich hlavním zájmem získat kontrolu nad obchodem pepř. V tomto sledovali muslimské Araby, které nakonec marginalizovali; a následně je následovali Holanďané v roce 1683. Britové a Francouzi také působili v oblasti nyní známé jako Kerala, první od roku 1615 a druhá od roku 1725. Tyto různé evropské mocnosti se spojily s tím či oním nairským panovníkem bojující o kontrolu.[18] Jedním z pozoruhodných spojenectví bylo spojenectví Portugalců s Královstvím Cochin, s nimiž se postavili na stranu, aby pracovali proti moci Zamorinů z Calicutu. Ačkoli Calicut zůstal nejvýznamnějším královstvím až do třicátých let 20. století, jeho moc byla narušena a vládci Cochinu byli osvobozeni od vazalů Zamorinů.[19]

Pokles dominance

V roce 1729 se Marthanda Varma stala rajou z Venadu a zdědila stát čelící válkám a žáruvzdorným náčelníkům Nairu. Varma omezila moc náčelníků Nairů a představila Tamila Brahminse, aby vytvořil základní součást jeho správy. [20] Za vlády Marthandy Varmy pěchota Travancore Nair (známá také jako Nair Pattalam ) se vyznamenali v bitvě proti Nizozemcům u Bitva u Colachel (1741).[21] Nairská armáda byla reorganizována v evropském stylu a transformovala se z feudální síly na stálou armádu. Ačkoli tato armáda byla stále tvořena Nairem, kontrolovala to moc místních náčelníků a byla to první hranice dominance Nairu. [20]

Během středověku došlo ke střetům mezi hinduisty a muslimy, zejména když odcházely muslimské armády Mysore napadl a získal kontrolu nad severní Kéralou v roce 1766. Nair Kottayam a Kadathanad vedl odpor a Nairům se podařilo porazit všechny mysorejské posádky kromě těch v Palakkadu. [22] Krátce nato Haider Ali zemřel a jeho syn Tipu se stal sultánem. Naíři z Calicutu a Jižního Malabaru dobyli Calicut znovu a porazili armádu vyslanou Tipuem, aby prolomila obležení. To způsobilo, že samotný sultán zasáhl v roce 1789, během kterého mnoho hinduistů, zejména Nairů, byli drženi v zajetí nebo zabiti muslimy pod Tipu sultán.[23] [24] Mnoho Nairů uprchlo pod ochranu Travancora, zatímco jiní se zapojili do partyzánské války. [24] Nairové z Travancoru však byli schopni porazit muslimské síly v roce 1792 u Třetí Anglo-Mysore válka. Poté Východoindická společnost si vybudovala prvenství v celém regionu Kerala.[25]

Britové uvalili další omezení dominance Nair. Po podpisu smlouvy o dceřiné alianci s Travancore v roce 1795 byli britští obyvatelé posláni do správy Travancore; zásah Britů způsobil dvě povstání v letech 1804 a 1809, z nichž druhá měla mít trvalé následky. Velu Thampi, Nair dewan z Travancore, vedl a vzpoura v roce 1809 odstranit britský vliv z Travancore sarkar.[28] Po několika měsících byla vzpoura poražena a Velu Thampi spáchal sebevraždu.[29] Poté byli Naíři rozpuštěni a odzbrojeni. Do této doby byl Nairs historicky vojenskou komunitou, která spolu s Nambudiri Brahmins vlastnil většinu půdy v regionu; poté se začali stále více věnovat administrativní službě.[30][31] Do této doby existovalo devět malých Nairských království a několik náčelníků, kteří k nim byli volně přidruženi; Britové sloučili sedm z těchto království (Calicut, Kadattunad, Kolattunad, Kottayam, Kurumbranad, Palghat a Walluvanad) a vytvořili Malabar District, zatímco Cochin a Travancore zůstali jako rodné státy pod kontrolou svých vlastních vládců, ale s radou Britů.[18] Vzpoura Velu Thampi způsobila, že Britové byli nazí před vůdci Nairu a Travancore sarkar byl hlavně pod kontrolou britských obyvatel, ačkoli zbytek administrativy z větší části řídili nemalajálští Brahminové a Nairs. [32]

Armáda Travancore se v letech 1818–1819 stala brigádou Travancore Nair.[27] Do této brigády byla rovněž začleněna jednotka Nair, 1. prapor vojsk HH Raniho, ale brigáda sloužila pouze v policejní funkci až do stažení vojsk Východoindické společnosti v roce 1836. V roce 1901 byla jednotka zbavena policejních povinností a byl umístěn pod britským důstojníkem.[26] V roce 1935 byl Travancore Nairský pluk a Maharadžův osobní strážce sloučeny a přejmenovány na Travancore State Force, jako součást Indické státní síly Systém.[26]

Změny v ekonomice a právním systému od konce 19. století zničily mnoho nairských tharavad. Vůdci Nair zaznamenali úpadek své komunity a snažili se vypořádat s problémy týkajícími se rozšířených bojů, nejednoty a sporů. To bylo v kontrastu s jinými komunitami, které se rychle spojily pro kastovní zájmy. [33][34][35] Do roku 1908 Nairové úplně neztratili svoji nadvládu; stále drželi většinu země a stále drželi většinu vládních funkcí, a to i přes konkurenci nízkocenových a křesťanů. Dominance, kterou si Nairs historicky držel z rituálního postavení, se dostala do opozice. Země, kterou historicky drželi Naíři, byla postupně ztracena, protože došlo k obrovské míře převodu bohatství na křesťany a avarné hinduisty. [36] [35] Křesťanští misionáři také našli zájem o rozpuštění tharavad, protože to považovali za příležitost k obrácení Nairů. [37]

V roce 1914 byla založena Nair Service Society (NSS) Mannathu Padmanabha Pillai. Vyrůstat v chudobě a být svědkem rozšířeného domácího zmatku a odcizení půdy mezi Nairy pomohlo Padmanabhanovi vytvořit NSS. Organizace měla za cíl reagovat na tyto problémy vytvořením vzdělávacích institucí, programů sociální péče a nahradit těžkopádné zvyky, jako je matrilineální systém.[38] [39]

Po indické nezávislosti na britské nadvládě se regiony Travancore, Malabar District a Cochin staly dnešním státem Kerala. Pokud jde o Nairy žijící v bývalých oblastech Cochin a South Malabar, které jsou někdy společně označovány jako centrální Kerala, existuje nejvíce informací; to, co je k dispozici pro severní Malabar, je nejchudší.[4] Dvě bývalé divize státní armády Travancore, 1. pěší pěchota Travancore Nayar a 2. pěší pěchota Travancore Nayar, byly po získání nezávislosti převedeny na 9. a 16. prapor madrasského pluku.[21] Nayarská armáda z Cochinu byla začleněna do 17. praporu.[40]

Kultura

Umění

Historicky nejvíce Nairů bylo gramotných v malabarština a mnoho v sanskrtu.[1][41][42] Vysvětlení této gramotnosti bylo přičítáno obecným potřebám správy, protože mnoho Nairů sloužilo jako zákoníci a soudní vykonavatelé pro královské dvory.[1][43] Mnoho Nairů se stalo významnými filozofy a básníky a od 16. století a dále Nairové stále více přispívali k literatuře a dramatu. Nairů z nejnižších podskupin komunity se také účastnily těchto uměleckých tradic.[44] V 19. století se romány napsané Nairem zabývaly tématy společenských změn. Tato témata by se primárně týkala vzestupu nukleární rodiny jako náhrady starého matrilineálního systému. [45] Romány, jako například Indulekha O.C Menon měl témata, která se zabývala společenskými omezeními romantické lásky, zatímco C.V Raman Pillai Marthanda Varma se zabýval tématy týkajícími se vojenské minulosti Nair. [46]

Kathakali je taneční drama, které zobrazuje scény ze sanskrtských eposů nebo příběhů.[47] Taneční drama historicky hrálo výhradně Nairs [48][49] a vždy s nimi byl tradičně spojován; Nairští vládci a náčelníci toto umění sponzorovali, první hry Ramanattamu napsal Nair z vládnoucí rodiny a Kathakali měl základy vojenského výcviku a náboženských zvyků v Nairu.[50] První herci z Kathakali byli s největší pravděpodobností nairští vojáci, kteří prováděli taneční drama na částečný úvazek, ovlivněni technikami Kalaripayattu. Jak se Kathakali vyvíjel jako umělecká forma, rostla potřeba specializace a detailů.[51] Ti, kteří se stali mistry umění, předali své tradice svým rodinám. Tyto rodiny byly zdrojem dalších generací studentů Kathakali a za učedníka byl často zvolen synovec pána. [52]

Oděv

Historickým oblečením nairských mužů bylo Mundu, kolem pasu obtočená tkanina a poté odešla viset dolů téměř k zemi, spíše než zastrčená jako v jiných částech Indie. Nízko visící tkanina byla považována za specifickou pro kastu Nair a na počátku 20. století bylo poznamenáno, že v konzervativnějších venkovských oblastech by mohl být porazen jiný než Nair, protože se odvážil nosit hadřík visící nízko nad zemí. Bohatí Naíři pro tento účel mohli použít hedvábí a také by si zakryli horní část těla kouskem přichyceného mušelínu; zbytek komunity kdysi nosil materiál vyrobený v Eraniyalu, ale v době psaní Panikkaru se obvykle používalo bavlněné plátno dovezené z Lancashire, Anglie, a nad pasem neměla nic na sobě. Nairští muži se vyhýbali turbanům nebo jiným pokrývkám hlavy, ale nosili by slunečník proti slunečním paprskům. Také se vyhýbali obuvi, i když někteří z bohatých nosili komplikované sandály.[60][61]

Historické šaty Nair ženy byly mundu, stejně jako tkanina, která zakrývala horní část těla. The mundum neryathum, oděv, který zhruba připomíná sari, se později stal tradičním oděvem nairských žen. [55][62]Šaty sestávaly z látky svázané kolem pasu a látky zakrývající prsa a bez blůzy. Mundum neryathum se stalo podstatou setového sárí, které je považováno za specifické regionální oblečení Keraly. Sonja Thomas popisuje, jak se jedná o příklad toho, jak „bylo dáno přednost kulturním normám vyšších kast“. [55] Nairské ženy by také nosily onera (onnara), bederní rouška, kterou nosí jako spodní prádlo konzervativnější ženy.[63][64] Bylo zaznamenáno, že spodní prádlo zkrášlovalo a zeštíhlovalo pas.[65]

Náboženství a rituál

Primární božstvo Nairů je Bhagavati, která je patronkou bohyně války a plodnosti. [66][67] Bhagavati, který je ústředním bodem všech aspektů života Nair a je uctíván jako laskavá a divoká panenská matka, se ztotožňuje se sanskrtskými i regionálními aspekty uctívání.[68] Bohyně byla uctívána v chrámech královských Nair matrilineages a také ve vesnici Nair matrilineages. [67] [69] Idol by byl buď umístěn na západní straně domu, nebo by byl umístěn v místnosti s jinými božstvy.[68] Kalaris by měl také prostor pro uctívání Kali, válečného projevu Bhagavatiho. [66]

Hadí božstva známá jako Nago Nairové byli uctíváni a tato božstva byla umístěna do háje v rodinném majetku. Háje zobrazovaly miniaturní les, který se podobal Patala a mohly by obsahovat různé typy idolů. [70] Uctívání Naga bylo významné pro celou tharavad, protože, jak říká Gough, „… mohly způsobit nebo odvrátit nemoc obecně, ale zejména se věřilo, že jsou odpovědné za plodnost nebo neplodnost tharavadských žen“.[71] Gough spekuluje, že Nagové byli považováni za falické symboly představující rozmnožovací schopnosti předků.[71]

Nairs věřil v duchy, které se při některých příležitostech pokoušeli zkrotit předváděním různých rituálů. Podle Panikkara věřili v duchy jako např Pretam, Bhutam a Pisachu. Pretam je duch předčasně mrtvých lidí; Bhutam, Panikkar říká, „je vidět obecně v bažinatých okresech a ne vždy ublíží lidem, pokud jdou velmi blízko něj“; a Pisachu je duch špatného vzduchu způsobujícího nemoci. Věřit Pretam aby se potulovali po místě smrti, varovali lidi, aby se zdržovali mimo tyto oblasti mezi 9:00 a 15:00.[73] Také věřili v komiksového elfa jménem Kutti Chattan, který by byl náchylný ke škodě.[74] Věřili ďábelské oko—Že komplimenty od ostatních měly negativní účinek; také věřili, že promluvy člověka s kari nakku (černý jazyk) měl podobně špatný účinek. Také věřili koti od chudáka, který sleduje někoho, kdo jí chutné jídlo, způsobí bolesti žaludku a úplavice.[75]

Rituály narození a smrti

Nair tradičně praktikoval určité rituály týkající se narození, i když často jen pro prvorozené. Z nich, pulicudi byl pro ně nejvýznamnější. Jednalo se o vtírání kokosového oleje do těhotné ženy, následovalo koupání, formální oblékání, konzultace s astrologem ohledně očekávaného data narození a slavnostní pití tamarind šťáva kapala podél meče meče. Žena by také vybrala zrno, ze kterého se věřilo, že je možné určit pohlaví dítěte. Tento rituál byl proveden před komunitou a obsahoval mnoho symbolických odkazů; například se věřilo, že použití meče z dítěte udělá válečníka.[76]

V měsících následujících po narození následovaly další rituály, včetně očistných a zdobení dítěte symbolickým opaskem k odvrácení nemoci, stejně jako ceremonie pojmenování, při které znovu hrál významnou roli astrolog. Existovala také různá dietní omezení, a to jak pro ženu během těhotenství, tak pro dítě v prvních měsících jejího života.[76]

Přestože se porod považoval za rituálně znečišťující, za smrt v rodině se považovalo mnohem více.[76] V případě úmrtí nejstaršího člena rodiny, ať už muže nebo ženy, by bylo tělo zpopelněno na hranici; pro všechny ostatní členy rodiny byl pohřeb normou. V obou případech obřady prováděla Maran podskupiny komunity a využívali jak prvky pověr, tak hinduismu. Příležitosti spojené s kremací byly rituálnější než ty, které zahrnovaly pohřeb.[77]

Po kremaci následovalo komplikované čtrnáctidenní období smutku, během něhož rodina kolem hranice prováděla různé symbolické činy a byla považována za rituální prostředí velmi znečištěná, což vyžadovalo nejen to, že se pravidelně koupali, ale také to, že každý další Nair, který může se jich dotknout, musí se také vykoupat. Po tomto období následovala hostina a účast na sportovních akcích, kterých se účastnily i Nairs z okolních vesnic. Následně rodina zůstala ve smutku, zatímco jeden mužský člen podnikl a dikša během této doby musel udržovat čistý život. Jednalo se o to, že žil s Brahminem, koupal se dvakrát denně a přestal si stříhat vlasy nebo nehty, stejně jako to, že mu bylo zabráněno mluvit se ženami nebo dokonce je vidět. V některých případech dikša může trvat déle než obvyklých čtyřicet jedna dní, v takovém případě by na jeho konci byla značná oslava.[77]

Strava

Vepřové maso bylo známé jako oblíbené jídlo Nair,[78] a dokonce i vysoce postavení Naíři byli známí tím, že jedli buvolí maso.[79]

Nair se vyhýbal hovězímu masu a mnozí nejedli jehněčí maso.[80] V moderní době je alkohol součástí festivalů v Kerale, kde dominují Nair.[79]

Sociální a politická organizace

Politická organizace

Před reorganizací regionu Brity byla Kerala rozdělena na přibližně deset feudálních států. Každý z nich byl řízen a rádža (král) a byl dále rozdělen na organizační jednotky známé jako nads. Na druhé straně nads byly rozděleny na dēsams.[81]

Osoba, která vládla nad byl známý jako naduvazhi. Byla to zděděná role, původně udělená králem, a nižší rituální hodnosti než královské linie. Ačkoli rodiny Nairů, obvykle používaly název Samantan a bylo s nimi zacházeno jako s vazaly. Někteří však naduvazhi byli feudální šéfové, bývalí králové, jejichž území ovládli například Zamorinové z Calicutu. V těchto případech, přestože se klaněli rádža v důsledku své delší historie vlády měli vyšší rituální hodnost než Zamorin; měli také více moci než vazalští náčelníci. The naduvazhi rodiny se každá viděla jako zřetelná kasta stejným způsobem jako rajahové; nepoznali jiné naduvazhi rodiny jako rovnocenné.[81] The naduvazhi udržoval trestní a civilní pořádek a mohl požadovat vojenskou službu od všech Nairů pod ním. K dispozici byla obvykle stálá síla mezi 500 a 1000 muži a tito byli povoláni rádža podle potřeby.[82] Všechny boje byly obvykle pozastaveny během monzunového období od května do září, kdy byl pohyb po celé zemi téměř nemožný. Silnice neexistovaly, ani kolová vozidla, ani smečka zvířat, až po roce 1766.[12]

The desavazhi měl právo pracovat kalaris, což byly vojenské výcvikové školy, které měli navštěvovat všichni mladí muži z Nairu od 12 let. Přestali navštěvovat ve věku 18 let, ale očekávalo se, že budou k dispozici pro vojenskou službu denně. Funkce těchto škol se stala méně významnou prakticky po zavedení zákona o zbraních Brity, který omezil právo Nairse nosit zbraně; nadále však existovali a poskytovali školení těm mužům z Nair, kteří nenavštěvovali anglické školy. Toto školení se projevilo na vesnických slavnostech, během nichž proběhla bojová revize.[82]

Podle Gougha měly vesnice obvykle rozlohu jeden až čtyři čtvereční míle a jejich pozemky obvykle vlastnila jedna rodina pronajímatele, která požadovala vyšší rituální hodnost než její ostatní obyvatelé. Pronajímatel byl také obvykle desavazhi (vedoucí) a ve všech případech byly jejich rodiny známé jako jenmis. Tito majitelé pocházeli z linií královských rodin nebo feudálních náčelníků; nebo to byly patrilineální rodiny Nambudiri nebo majetky chrámů provozované skupinami těchto rodin. Byli také z linií matrilineálních vazalských samantanských náčelníků a nakonec nejnižších jenmis pokud jde o rituální pořadí, byli Nairs, kteří zdědili po matrilineálních předcích, jimž král a král udělili půdu a souběžné vedení. Ve všech případech nemohly být statky prodány bez královského povolení.[81]

Vesnice byly historicky většinou soběstačné a v každé z nich byly řemeslné řemesla jako hrnčířství a kovářství. To znamenalo, že nebylo potřeba úzké centrální kontroly vyššími úrovněmi v organizační hierarchii, a také to znamenalo, že obchod mezi vesnicemi byl minimální. Tito obchodníci, kteří existovali, se většinou soustředili v přístavních městech a sestávali z imigrantských Syřanů, muslimů, křesťanů a Židů, přičemž hinduističtí obchodníci později přijížděli z jiných částí Indie, stejně jako Evropané.[12] Naíři byli jedinými členy vesnických organizací, které existovaly pro účely správy záležitostí chrámů a organizování vojenského výcviku a nasazení. Rodina Nairů byla považována za součást vesnické organizace, i když se od ní odstěhovali. V těchto vesnicích byly i jiné kasty a další náboženské skupiny, které však byly z organizací vyloučeny. Toto uspořádání se lišilo od uspořádání jinde v Indii a další rozdíl spočíval v tom, že každý dům, ať už pro Nairs nebo jinak, byl obvykle ve svém vlastním areálu. Neexistovala žádná obecní půda, jaká existovala jinde, a žádný společný plán pro uspořádání vesnice.[82]

Naíři nesměli provádět obřady v chrámech sanketams, vesnice, kde půdu vlastnila skupina rodin Nambudiri, i když by mohly mít přístup do oblasti vnějšího nádvoří. Někdy v těchto vesnicích nebyl vůbec žádný Nairs. Ve vesnicích, kde existovaly chrámy, které byly v soukromém vlastnictví jedné rodiny Nambudiri, by existoval další chrám zasvěcený Bhagavadi, který používali Naíři. Právě ve vesnicích, kde Naíři zahrnovali vůdce, mohl existovat jen jediný chrám, provozovaný jejich vesnickou organizací.[83]

Sociální organizace

Na konci 19. století se kastovní systém Kerala vyvinul jako nejsložitější, jaký lze v Indii najít. Ve složité struktuře vztahů bylo zastoupeno více než 500 skupin a koncept rituálního znečištění se rozšířil nejen na nedotknutelnost ale ještě dále, aby nepřístupnost. Systém byl do jisté míry postupně reformován, přičemž jeden z těchto reformátorů Svámí Vivekananda poté, co si všiml, že představuje „šílený dům“ kast. Obvyklý čtyřstupňový hinduistický kastovní systém zahrnující varny z Bráhman (kněz), Kshatriya (bojovník), Vaishya (podnikatel zapojený do obchodování, podnikání a financí) a Shudra (servisní osoba), neexistoval. Kshatriyas byly vzácné a Vaishyas vůbec nebyli přítomni. Role, které zůstaly prázdné kvůli absenci těchto dvou rituálních řad, byly do jisté míry převzaty několika Nairy a neinduistickými přistěhovalci.[84]

Nambudiri Brahminové byli na vrcholu hierarchie rituální kasty a v tomto systému převyšovali dokonce i krále.[85] Považovali všechny Nairy za shudra. Pod Nambudiris přišel Tamil Brahmins a další pozdější přistěhovalci Brahminů varna. Kromě toho podléhá přesné hodnocení určitým rozdílům v názorech. Kodoth umístil Samantan kasta pod hodností Kshatriya, ale nad Nairs, ale Gough se domnívá, že Pushpagans a Chakyars, oba byli nejlépe hodnoceni ve skupině chrámových služebníků známých jako Ambalavasis, byli zařazeni mezi Brahmany a Nairy, stejně jako několik dalších členů skupiny Ambalavasi.[86] Věří také, že někteří Naíři přijali titul Samantan, aby zdůraznili svou nadřazenost nad ostatními ve své kastě.[81] Neochota vyšších varny zapojit se do činností, které považují za znečišťující průmyslové a obchodní činnosti, se uvádí jako důvod pro relativně omezený ekonomický rozvoj regionu.[84][87][88]

Keralitské tradice zahrnovaly, že určitým komunitám nebylo dovoleno v dané vzdálenosti od jiných kast s odůvodněním, že by „znečišťovaly“ relativně vyšší skupinu. Například, Dalité byly zakázány do 64 stop.[89] Podobně se Nair mohl přiblížit, ale nedotknout se Nambudiri.[90]

Podskupiny

Naíři se identifikují jako v mnoha podskupinách a vedla se debata o tom, zda by tyto skupiny měly být považovány za subcasty nebo za směs těchto subdivizí. Bylo několik pokusů tyto různé skupiny identifikovat; většina z nich byla před koncem britské správy v Indii, ale Kathleen Gough se této problematice věnovala také v roce 1961. Tyto analýzy mají podobnosti s Jatinirnayam Malayamské dílo, které vyjmenovalo 18 hlavních podskupin podle zaměstnání, včetně bubeníků, obchodníků, měďáků, nositelů nosítek, služebníků, hrnčířů a holičů, a také hodností jako Kiriyam a Illam. Ačkoliv Jatinirnayam sám nerozlišoval žádné konkrétní podskupiny od vyšších, následné pokusy o klasifikaci tak učinily, když prohlásily různá povolání za tradiční a uvedly, že vojáky byly pouze vyšší skupiny. Antropologové, etnologové a další autoři se domnívají, že příjmení Nair bylo titulem, který označoval podskupinu (vibhagam), ke kterému tato osoba patřila, a označila povolání, které osoba sledovala nebo jí bylo uděleno náčelníkem nebo králem. Tato jména zahrnuta Nair sám, Kurup, Menon, a Pillai.[91]

| Nairské dělení v sestupném pořadí podle standardních popisů, sestavené C J Fullerem v roce 1975[92] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hodnocení | Jatinirnayam[b] | Aiya (1906)[C] | Iyer (1912)[d] | Innes (1908)[E] | Gough (1961)[F] |

| 1 | Kiriyam | Kiriyam | Kiriyam | Kiriyam | Kiriyam |

| 2 | Illam | Illam | Illam | Purattu Charna | Purattu Charna |

| 3 | Svarupam | Svarupam | Svarupam | Akattu Charna | Akattu Charna |

| 4 | Padamangalam | Padamangalam | Purattu a Akattu Charna | Illam | Pallicchan |

| 5 | Tamil Padam | Tamil Padam | Menokki | Mutta | Illam |

| 6 | Itasseri | Itasseri | Maran | Taraka | Vattakkatan |

| 7 | Maran | Maran | Padamangalam | Ravari | Otattu |

| 8 | Chempukotli | Chempukotli | Pallicchan | Anduran | Anduran |

| 9 | Otattu | Otattu | Vattakkatan | Otattu | Asthikkuracchi |

| 10 | Pallicchan | Kalamkotti | Chempukotti | Pallicchan | Veluttetan |

| 11 | Matavan / Puliyath | Vattakkatan | Otattu | Urali | Vilakkittalavan |

| 12 | Kalamkotti / Anduran | Pallicchan | Itasseri | Chempukotti | |

| 13 | Vattakkatan / Chakkala | Asthikkuracchi | Anduran | Vattakkatan | |

| 14 | Asthikkuracchi / Chitikan | Chetti | Asthikkuracchi | Asthikkuracchi / Chitikan | |

| 15 | Chetti | Chaliyan | Tarakan | Kulangara | |

| 16 | Chaliyan | Veluttetan | Vilakkittalavan | Itasseri | |

| 17 | Veluttetan | Vilakkittalavan | Veluttetan | Veluttetan | |

| 18 | Vilakkittalavan | Chaliyan | Vilakkittalavan | ||

| 19 | Kaduppattam | ||||

| 20 | Chaliyan | ||||

Přehodnocení širokého systému klasifikace proběhlo od konce 50. let. Fuller, který psal v roce 1975, tvrdí, že přístup ke klasifikaci pomocí titulárních jmen byl mylnou. Lidé si mohli a udělovali tituly; a při příležitostech, kdy byl titul ve skutečnosti udělen, to nicméně neznamenalo jejich podskupinu. Tvrdí, že široký obrys členění

... ztělesňuje, abych tak řekl, kastovní systém v kastovním systému. S výjimkou vysoce postavených kněží zrcadlí Nayarské subdivize všechny hlavní kastovní kategorie: vysoce postavení šlechtici, vojenští a přistáli; řemeslníci a služebníci; a nedotknutelní. Ale ... tato struktura je spíše ideální než skutečná.[91]

M. N. Srinivas v roce 1957 zjistil, že „Varna byl model, kterému byly přizpůsobeny pozorované skutečnosti, a to platí nejen pro vzdělané Indy, ale do jisté míry i pro sociology. “Namísto nezávislé analýzy struktury podskupin je komentátoři vysvětlili nevhodně pomocí existujícího ale mimozemská sociální struktura. Z této nevhodné metodiky vycházela představa, že skupiny byly spíše subcasty než subdivize.[93] V roce 1966 rovněž tvrdil, že „někteří Nayarové„ dozráli “do Samantanů a Kšatrijů. Například královské linie Calicut, Walluvanad, Palghat a Cochin, i když byly Nayarského původu, se považovaly za rajské hodnosti nadřazené svým Nayarským poddaným. " That is to say, they assumed a position above the status that they were perceived as being by others.[94]

The hypothesis, proposed by writers such as Fuller and Louis Dumont, that most of the subgroups were not subcastes arises in large part because of the number of ways in which Nairs classified themselves, which far exceeded the 18 or so groups which had previously been broadly accepted. Dumont took the extreme view that the Nairs as a whole could not be defined as a caste in the traditional sense, but Fuller believed this to be unreasonable as, "since the Nayars live in a caste society, they must evidently fit into the caste system at some level or another." The 1891 sčítání lidu Indie listed a total of 128 Nair subgroups in the Malabar region and 55 in the Cochin region, as well as a further 10 in the Madras area but outside Malabar. There were 44 listed in Travancore in the census of 1901. These designations were, however, somewhat fluid: the numbers tended to rise and fall, dependent upon which source and which research was employed; it is likely also that the figures were skewed by Nairs claiming a higher status than they actually had, which was a common practice throughout India. Data from the late 19th-century and early 20th-century censuses indicates that ten of these numerous subdivisions accounted for around 90% of all Nairs, that the five[G] highest ranking of these accounted for the majority, and that some of the subdivisions claimed as little as one member. The writer of the official report of the 1891 census, H A Stuart, acknowledged that some of the recorded subdivisions were in fact merely families and not subcastes,[96] and Fuller has speculated that the single-member subdivisions were "Nayars satisfying their vanity, I suppose, through the medium of the census."[97]

The revisionist argument, whose supporters also include Joan Mencher, proposes a mixed system. The larger divisions were indeed subcastes, as they demonstrated a stability of status, longevity and geographic spread; however, the smaller divisions were fluid, often relatively short-lived and narrow in geographic placement. These divisions, such as the Veluttetan, Chakkala a Vilakkittalavan, would take titles such as Nair nebo Nayar in order to boost their social status, as was also the practice with other castes elsewhere, although they were often not recognised as caste members by the higher ranks and other Nairs would not marry with them. It has also been postulated that some exogamní families came together to form small divisions as a consequence of shared work experiences with, for example, a local Nambudiri or Nair chief. These groups then became an endogamní subdivision, in a similar manner to developments of subdivisions in other castes elsewhere.[98] The more subdivisions that were created, the more opportunity there was for social mobility within the Nair community as a whole.[99]

Even the highest ranked of the Nairs, being the kings and chiefs, were no more than "supereminent" subdivisions of the caste, rather than the Kshatriyas and Samantans that they claimed to be. Their claims illustrated that the desires and aspirations of self-promotion applied even at the very top of the community and this extended as far as each family refusing to admit that they had any peers in rank, although they would acknowledge those above and below them. The membership of these two subgroups was statistically insignificant, being a small fraction of 1 per cent of the regional population, but the example of aspirational behaviour which they set filtered through to the significant ranks below them. These subdivisions might adopt a new name or remove themselves from any association with a ritually demeaning occupation in order to assist their aspirations. Most significantly, they adopted hypergamie and would utilise the rituals of thalikettu kalyanam a sambandham, which constituted their traditional version of a marriage ceremony, in order to advance themselves by association with higher-ranked participants and also to disassociate themselves from their existing rank and those below.[100]

Attempts to achieve caste cohesion

The Nair Service Society (NSS) was founded in 1914. Nossiter has described its purpose at foundation as being "... to liberate the community from superstition, taboo and otiose custom, to establish a network of educational and welfare institutions, and to defend and advance Nair interests in the political arena."[38] Devika and Varghese believe the year of formation to be 1913 and argue that the perceived denial of 'the natural right' of upper castes to hold elected chairs in Travancore, a Hindu state, had pressured the founding of the NSS.[101]

As late as 1975, the NSS still had most of its support in the Central Travancore region,[102] although it also has numerous satellite groups around the world.

From its early years, when it was contending that the Nairs needed to join together if they were to become a political force, it argued that the caste members should cease referring to their traditional subdivisions and instead see themselves as a whole. Census information thereafter appears to have become unreliable on the matter of the subdivisions, in part at least because of the NSS campaign to ensure that respondents did not provide the information requested of them. The NSS also promoted marriage across the various divisions in a further attempt to promote caste cohesion, although in this instance it met with only limited success. Indeed, even in the 1970s it was likely that cross-subdivision marriage was rare generally, and this was certainly the case in the Central Travancore area.[102]

It has been concluded by Fuller, in 1975, that

... the question of what the Nayar caste is (or was): it is a large, named social group (or, perhaps preferably, category) with a stable status, vis-a-vis other castes in Kerala. It is not, however, a solidary group, and, the efforts of the N.S.S. notwithstanding, it is never likely to become one.[3]

The influence of the NSS, both within the community and in the wider political sphere, is no longer as significant as once it was. It did attempt to reassert its influence in 1973, when it established its own political party—the National Democratic Party—but this lasted only until 1977.[103]

Současnost

Today, the government of India does not treat the Nair community as a single entity. It classifies some, such as the Illathu and Swaroopathu Nairs, as a forward caste but other sections, such as the Veluthedathu, Vilakkithala and Andhra Nairs, as Další zpětné třídy.[104] These classifications are for the purpose of determining which groups of people in certain areas are subject to pozitivní diskriminace policies for the purposes of education and employment.

Historical matrilineal system

Tharavad

Nairs operated a matrilineal (marumakkathayam ) joint family structure called tharavad, whereby descendant families of one common ancestress lived under a single roof. Tharavads consisting of 50 to 80 members were not uncommon and some with membership as high as 200 have been reported. Only the women lived in the main house; men lived in separate rooms[je zapotřebí objasnění ] and, on some occasions, lived in a separate house nearby. The families split on instances when they became unwieldy and during crisis among its members. When it split, the family property was separated along the female lines. The karnavan, the oldest male member in the tharavad, had the decision-making authority including the power to manage common property. Panikkar, a well-known writer from the Nair community, wrote in 1918 that,

Authority in the family is wielded by the eldest member, who is called karnavan. He has full control of the common property, and manages the income very much as he pleases. He arranges marriages (sambandhams) for the boys as well as the girls of the family. He had till lately full power (at least in practice) of alienating anything that belonged to them. His will was undisputed law. This is, perhaps, what is intended to be conveyed by the term Matri-potestas in communities of female descent. But it should be remembered that among the Nayars the autocrat of the family is not the mother, but the mother's brother.[105]

The husband visited the tharavad at night and left the following morning and he had no legal obligation to his children which lay entirely with the karnavan.[106] In Nair families, young men and women about the same age were not allowed to talk to each other, unless the young man's sister was considerably older than him. Manželka karnavan had an unusual relationship in his tharavad as she belonged to a different one and her interests lay there. Panikkar wrote that Karnavan loved his sister's son more than his own and he believes it was due mainly to the instability of Nair marriages. Divorce rate was very high as both man and woman had equal right to terminate the marriage. Enangar was another family with which a tharavad remained closely related; a few such related families formed a social group whose members participated in all social activities.[105] Nakane wrote in 1956 that tharavads as a functional unit had ceased to exist and large buildings that had once hosted large tharavads were occupied by just a few of its remnants.[106]

Manželský systém

Fuller has commented that "The Nayars' marriage system has made them one of the most famous of all communities in anthropological circles",[107] and Amitav Ghosh says that, although matrilineal systems are not uncommon in communities of the south Indian coast, the Nairs "have achieved an unparalleled eminence in the anthropological literature on matrilineality".[108] None of the rituals survive in any significant way today. Two forms of ritual marriage were traditional:[109]

- the pre-puberty rite for girls known as thalikettu kalyanam, which was usually followed by sambandham when they became sexually mature. The sambandham was the point at which the woman might take one or more partners and bear children by them, giving rise to the theories of them engaging in polyandrous praktik. A ritual called the tirandukuli marked the first menstruation and usually took place between these two events.[110]

- a form of hypergamy,[h] whereby high-ranked Nairs married Samantans, Kshatriyas and Brahmins.

There is much debate about whether the traditional Nair rituals fitted the traditional definition of marriage and which of thalikettu kalyanam nebo sambandham could lay claim to it.[112][113] Thomas Nossiter has commented that the system "was so loosely arranged as to raise doubts as to whether 'marriage' existed at all."[114]

Thalikettu kalyanam

The thali is an emblem shaped like a leaf and which is worn as a necklace. The wearing of it has been compared to a wedding ring as for most women in south India it denotes that they are married. The thalikettu kalyanam was the ritual during which the thali would be tied on a piece of string around the neck of a Nair girl. If the girl should reach puberty before the ceremony took place then she would in theory have been out-caste, although it is probable that this stricture was not in fact observed.[115]

The ritual was usually conducted approximately every 10–12 years for all girls, including infants, within a tharavad who had not previously been the subject of it. Higher-ranked groups within the caste, however, would perform the ritual more frequently than this and in consequence the age range at which it occurred was narrower, being roughly between age 10 and 13. This increased frequency would reduce the likelihood of girls from two generations being involved in the same ceremony, which was forbidden. The karnavan organised the elaborate ritual after taking advice from prominent villagers and also from a traditional astrologer, known as a Kaniyan. A pandal was constructed for the ceremony and the girls wore ornaments specifically used only on those occasions, as well as taking a ritual bath in oil. The ornaments were often loaned as only a few villagers would possess them. The person who tied the thali would be transported on an elephant. The higher the rank of that person then the greater the prestige reflected on to the tharavad, a také naopak[116] since some people probably would refuse to act as tier in order to disassociate themselves from a group and thereby bolster their claims to be members of a higher group. Although information is far from complete, those who tied the thali for girls of the aristocratic Nair families of Cochin in Central Kerala appear to have been usually Samantans, who were of higher rank, or occasionally the Kshatriyas, who were still higher. The Nambudiri Brahmins of Central Kerala acted in that role for the royal house of Cochin (who were Kshatriyas), but whether they did so for other Kshatriyas is less certain. The Kshatriyas would tie for the Samantans.[117] Mít thali of each girl tied by a different man was more prestigious than having one tier perform the rite for several girls.[118] The thali tying was followed by four days of feasting, and on the fourth day the marriage was dissolved.[119]

The girl often never saw the man who tied the thali again and later married a different man during the sambandham. However, although she neither mourned the death of her sambandham husband nor became a widow, she did observe certain mourning rituals upon the death of the man who had tied her thali. Panikkar argues that this proves that the real, religious marriage is the thalikettu kalyanam, although he also calls it a "mock marriage". He believes that it may have come into existence to serve as a religious demarcation point. Sexual morality was lax, especially outside the higher ranks, and both relationship break-ups and realignments were common; the thali kalyanam legitimised the marital status of the woman in the eyes of her faith prior to her becoming involved in the amoral activities that were common practice.[120]

It has been noted that there were variations to the practice. Examples include that the person who tied the thali might be a close female relative, such as the girl's mother or aunt, and that the ceremony conducted by such people might take place outside a temple or as a small ceremony at the side of a more lavish thalikettu kalyanam spíše než v tharavadu. These variations were probably exceptional and would have applied to the poorest families.[122] Fuller has also remarked that if each girl had her own thali tier, rather than one being used to perform the ritual for several girls at the same ceremony, then this presented the possibility of a subsequent divergence of status with the matrilineal line of the tharavadu, leading to more subdivisions and a greater chance that one or more of the girls might advance their status later in life.[123]

Sambandham

Panikkar says that for Nairs the real marriage, as opposed to a symbolic one, was sambandham, a word that comes from Sanskrt and translates as "good and close union". The Nair woman had sambandham relationships with Brahmins and Kshatriyas, as well as other Nairs. He is of the opinion that the system existed principally to facilitate the wedding of Nair women to Nambudiri Brahmins. In the Malabar region, only the eldest male member of a Brahmin family was usually allowed to marry within their caste. There were some circumstances in which a younger male was permitted to do so, these being with the consent of the elder son or when he was incapable of marriage. This system was designed to protect their traditions of patrilineality and prvorozenství. A consequence of it was that the younger sons were allowed to marry women from the highest subdivisions of the Nair caste. The Nair women could marry the man who had tied their thali, provided that he was not otherwise restricted by the rules that women were not permitted to marry a man from a lower caste or subdivision, nor to marry anyone in the direct matrilineal line of descent (however far back that may be) or close relatives in the patrilineal line, nor a man less than two years her senior.[84][115][124]

The sambandham ceremony was simple compared to the thalikettu kalyanam, being marked by the gift of clothes (pudava) to the bride in front of some family members of both parties to the arrangement. There might also be other gifts, presented at the time of the main Malayam festivals. Pokud sambandham partner was a Brahmin man or the woman's father's sister's son (which was considered a proper marriage because it was outside the direct line of female descent) then the presentation was a low-key affair. Nicméně, sambandham rituals were more elaborate, sometimes including feasts, when a "stranger" from within the Nair caste married the woman. The ceremony took place on a day deemed to be auspicious by priests.[115][124]

The sambandham relationship was usually arranged by the karanavan but occasionally they would arise from a woman attracting a man in a temple, bathing pool or other public place. První sambandham of a man was deemed to be momentous and his ability to engage in a large number of such relationships increased his reputation in his community. Sambandham relationships could be broken, due to differences between the spouses or because a karavanan forced it due to being pressured by a man of higher rank who desired to marry the woman.[113] Marriage by sambandham was neither legally recognised nor binding. The relationship could end at will and the participants could remarry without any ramifications. Attempts to regulate sambandham marriages by the Nayar Regulation Act of 1912 in Travancore and the Malabar Marriage Act of 1896 in British Malabar were not very successful.[124]

Any children borne by the woman had to be claimed by one of her sambandham partners if she was to avoid being out-caste, sold into slavery or even executed. There was a presumption that unclaimed children were the consequence of her having a relationship with a man from a lower caste, which could not be the case if the child was claimed because of the caste restrictions imposed in the selection of sambandham partneři:

... a caste is a bilateral grouping and a child's place in the caste society cannot be determined by only one parent. Further, the Indian system of status attribution, under most circumstances, proscribes sexual relations between a woman and a man of status lower than herself, and generally denies to any children born of such a union membership of either parent's caste. For these reasons, some recognition of paternity and an assurance that the genitor is of the right status is necessary - even if it is only the minimal one of a man asserting paternity.[125]

Hypergamie

The Nambudiri Brahmin tradition which limited the extent of marriage within their own caste led to the practice of hypergamy. Gough notes that

These hypergamous unions were regarded by Brahmans as socially acceptable concubinage, for the union was not initiated with Vedic rites, the children were not legitimized as Brahmans, and neither the woman nor her child was accorded the rights of kin. By the matrilineal castes, however, the same unions were regarded as marriage, for they fulfilled the conditions of ordinary Nayar marriage and served to legitimize the child as an acceptable member of his matrilineal lineage and caste.[126]

The disparity in caste ranking in a relationship between a Brahmin man and a Nair woman meant that the woman was unable to live with her husband(s) in the Brahmin family and so remained in her own family. The children resulting from such marriages always became Nairs. Panikkar argues that it is this type of relationship that resulted in the matrilineal and matrilocal system.[127] It has also been argued that the practice, along with judicious selection of the man who tied the thali, formed a part of the Nair aspirational culture whereby they would seek to improve their status within the caste. Kromě toho

... among the higher-ranking Nayars (and Kshatriyas and Samantans) in contradistinction to the "commoner" Nayars, no two subdivisions admitted to equal status. Thus the relations set up by the tall-rite [ie: the thalikettu kalyanam] and the sambandham union were always hypergamous.[119]

Although it is certain that in theory hypergamy can cause a shortage of marriageable women in the lowest ranks of a caste and promote upwards social movement from the lower Nair subdivisions, the numbers involved would have been very small. It was not a common practice outside the higher subcaste groups.[128]

Polyandry

Fuller argues that there is overwhelming evidence that Nair women as well as men had more than one sambandham partner at the same time, that "both men and women could have several partners at once, and either party was free to break the relationship, for any reason or for none, whenever they wished."[115]

He believes that both polyandrous sambandhams and hypergamy were most common in Central Kerala. In northern Travancore there appears not to have been as great a prevalence of hypergamy because of a relative scarcity of Brahmins living there. Fuller believes that in the relatively undocumented southern Travancore monogamie may have been predominant, and that although the matrilineal joint family still applied it was usually the case that the wife lived with the tharavad jejího manžela.[129][130]

Nancy Levine and Walter Sangree state that while Nair women were maritally involved with a number of men, the men were also married to more than one woman. The women and their husbands did not live together and their relationship had no meaning other than "sexual liaison" and legitimacy for the children.[131]

Gough has gone further than Fuller with regard to the interpretation of events in the north, believing that there is no evidence of polyandry in that area at all. She argues that all European travelogues describing polyandry came from the region of Central Kerala. Gough notes the differing personal experiences of earlier Nair commentators and that this could go some way to explaining the varied pronouncement: Panikkar, who queries the existence of polyandry, comes from the northern Travancore region; že A. Aiyappan, who acknowledges its existence, comes from Central Kerala; and that both have based their writings on customs they grew up with in their very different environs.[130]

Decline of traditional practices

The practices of thalikettu kalyanam, the polyandrous sambandhams, and also the existence of large tharavads declined during the nineteenth century, as did that of hypergamy. Monogamy and small nuclear family units became the norm, as they were elsewhere in the country. This process occurred more rapidly in some areas than in others, and in Central Kerala the traditional systems still lingered as late as the 1960s, although hypergamy had largely disappeared everywhere by the 1920s.[136] A possible reason for the various rates of change across the region lies in the extent to which the various agrarian local economies were dominated by the Nairs.[103]

V. K. S. Nayar has said that, "the matrilineal system tends to produce a society at once hierarchical and authoritarian in outlook. The system is built round family pride as well as loyalty to the karavanar".[137] Nossiter cites this as one reason why it was "congruent with the role of a military caste in a feudal society."[38] and explains that the decline in the traditional warrior role, the rise of an economy based on money, together with the ending of agricultural slavery and the effects of western education, all combined to cause the decline of the traditional practices. All of these factors were having an impact during the 19th-century and they caused erosion of the social dominance which the Nairs once held, eventually reaching a point some time between první světová válka a druhá světová válka where that dominance was lost,[30] although there was an attempt to reassert it in Travancore during the 1930s when the Diwan Sir C. P. Ramaswamy Iyer adopted a pro-Nair stance and an oppressive attitude towards communities such as the Syrian Christians.[138][i] The main beneficiaries in the shifting balance of social influence were the Syrian Christians and the Ezhavas. The former, in particular, were in a position to acquire, often by subdivision, the economically unviable tharavad buildings and landholdings around the time of the Velká deprese. The role of the Nair Service Society in successfully campaigning for continued changes in practices and legislation relating to marriage and inheritance also played its part.[30] This collapse of the rural society facilitated the rise of the socialist and communist political movements in the region.[103]

Demografie

The 1968 Socio-Economic Survey by the Government of Kerala gave the population of the Nair community as approximately 14.5% (2.9 million) of the total population of the state.[107]

Viz také

- C. Krishna Pillai

- List of Nairs

- Nambiar

- Mamankam

- Moopil Nair

- Onnu Kure Áyiram Yogam

- Nair ceremonies and customs

Reference

Poznámky

- ^ Gough quotes Ayyar (1938) for the statement on Lokar

- ^ Quoted by Fuller, citing K. P. Padmanabha Menon, Historie Kerala, volume 3 (1933), pp. 192–195

- ^ Quoted by Fuller, citing V. Nagam Aiya, Státní příručka Travancore, volume 2 (1906), pp. 348–349

- ^ Quoted by Fuller, citing L. K. Anantha Krishna Iyer, Cochinské kmeny a kasty, volume 2 (1912), pp. 14–18

- ^ Quoted by Fuller, citing C. A. Innes, Místopisní úředníci v Madrasu: Malabar a Anjengo, (ed. F. B. Evans), volume 1 (1908), pp. 116–120

- ^ Quoted by Fuller, citing E. Kathleen Gough, Nayar, Central Kerala v Matrilineální příbuzenství, (ed. D. M. Schneider & E. K. Gough), (1961), pp. 308–312

- ^ Fuller names the five highest subdivisions as Kiriyam, Illam, Svarupam, Purattu Charna and Akattu Charna. Of the other five main subdivisions, the Chakkala and Itasseri were to be found in Travancore and the Pallicchan, Vattakkatan and Asthikkuracchi in Cochin and Malabar.[95]

- ^ There are differences in the form of hypergamy common to south India and that which existed in north India, and these have been subject to much academic discussion.[111]

- ^ Postoj Sir C. P. Ramaswamy Iyer during the 1930s reflected a concern among Hindus that the Christian population of Travancore was rising and that there was a consequent danger of the region becoming a Christian state. The 1931 census recorded over 31 per cent of the population as being Christian, compared to around 4 per cent in 1820.[138]

Citace

- ^ A b C d Goody 1975, str. 132.

- ^ A b Gough (1961), str. 312

- ^ A b Fuller (1975) str. 309

- ^ A b Fuller (1975) str. 284

- ^ K. Balachandran Nayar (1974). In quest of Kerala. Publikace Accent. str. 85. Citováno 3. června 2011.

The Dravidian people of Kerala were serpent worshippers.

- ^ L. A. Krishna Iyer (1968). Social history of Kerala. Publikace knižního centra. str. 104. Citováno 3. června 2011.

- ^ K. R. Subramanian; K. R. Subramanian (M.A.) (1985) [1929]. The origin of Saivism and its history in the Tamil land (Přetištěno ed.). Asijské vzdělávací služby. str. 15–. ISBN 978-81-206-0144-4. Citováno 3. června 2011.

- ^ Narayanan (2003), str. 59

- ^ Fuller (1976) str. 1

- ^ Fuller (1976) pp. 7-8

- ^ A b Blankenhorn 2007, str. 106.

- ^ A b C Gough (1961), pp. 302–303

- ^ Gough (1961), str. 302–304

- ^ Almeida 2017, str. 92.

- ^ A b C Bock & Rao 2000, str. 185.

- ^ A b Fuller (1976) str.15

- ^ Fuller (1976) 7-9

- ^ A b C Gough (1961), str. 304

- ^ Gough (1961), str. 305

- ^ A b Jeffrey 1994, str. 4-5.

- ^ A b Gautam Sharma (1 December 1990). Odvaha a oběť: slavné pluky indické armády. Allied Publishers. str. 59–. ISBN 978-81-7023-140-0. Citováno 3. června 2011.

- ^ Menon 2011, str. 158.

- ^ Prabhu, Alan Machado (1999). Sarasvatiho děti: Historie mangaloreanských křesťanů. I.J.A. Publikace. str. 250. ISBN 978-81-86778-25-8.

- ^ A b Menon 2011 158-161

- ^ Eggenberger, David (1 September 1985). Encyklopedie bitev: účty více než 1560 bitev z roku 1479 př. N.l. do současnosti. Publikace Courier Dover. str.392 –. ISBN 978-0-486-24913-1. Citováno 6. června 2011.

- ^ A b C D. P. Ramachandran (October 2008). Empire's First Soldiers. Vydavatelé lancerů. str. 284–. ISBN 978-0-9796174-7-8. Citováno 6. června 2011.

- ^ A b "Army of Travancore". REPORT OF THE ADMINISTRATIVE REFORMS COMMITTEE 1958. Vláda Kéraly. Archivovány od originál dne 16. prosince 2006. Citováno 19. února 2007.

- ^ Jeffrey 1994, str. 5.

- ^ Jeffrey 1994, str. 6.

- ^ A b C Nossiter (1982) 27–28

- ^ G. Ramachandra Raj (1974). Functions and dysfunctions of social conflict. Populární Prakashan. str. 18. Citováno 2. června 2011.

- ^ Jeffrey 1994, s. 6-8.

- ^ Jeffrey 1994, pp. 177-181.

- ^ Jeffrey 1994, str. 234.

- ^ A b Jeffrey 1994, str. 267.

- ^ Jeffrey 1994, str. xviii-xix.

- ^ Jeffrey 1994 193

- ^ A b C Nossiter (1982) str. 28

- ^ Jeffrey 2016 102-104

- ^ Sharma, Gautam (1990). Odvaha a oběť: slavné pluky indické armády. Allied Publishers. str. 59. ISBN 978-81-7023-140-0. Citováno 4. května 2011.

- ^ Gough (1961) 337-338

- ^ Clark-Deces 2011, str. 1976.

- ^ Goody 1975, str. 147-148.

- ^ Goody 1975, str. 146.

- ^ Mukherjee 2002, str. 65.

- ^ Sarkar 2014, str. 138.

- ^ Goody 1975, str. 143.

- ^ Ashley 1979, str. 100.

- ^ Zarrilli 1984, str. 52.

- ^ Wade a kol. 1987, str. 27.

- ^ Zarrilli 1984, str. 74.

- ^ Zarrilli 1984 74-75

- ^ Gopinath 2018, str. 40.

- ^ Bald et al. 2013, str. 289.

- ^ A b C Thomas 2018, str. 38.

- ^ Arunima 1995, str. 167.

- ^ Gopinath 2018, str. 41.

- ^ Arunima 2003, str. 1.

- ^ Jacobsen 2015, str. 377.

- ^ Fawcett (1901) str. 254.

- ^ Panikkar (1918) str. 287–288.

- ^ Lukose 2009, str. 105.

- ^ Sinclair-Brull, Wendy (1997). Female ascetics: hierarchy and purity in an Indian religious movement. Psychologie Press. str. 148. ISBN 978-0-7007-0422-4. Citováno 6. června 2011.

- ^ University of Kerala (1982). Journal of Kerala studies. University of Kerala. str. 142. Citováno 6. června 2011.

- ^ Das, Kamala (2003). A childhood in Malabar: a memoir. Trans. Gita Krishnankutty. Knihy tučňáků. str. 76. ISBN 978-0-14-303039-3. Citováno 6. června 2011.

- ^ A b C Massey 2004, str. 106.

- ^ A b C Vickery 1998, str. 154.

- ^ A b Zarrilli 2003, str. 131.

- ^ Stone & King 2018, str. 149.

- ^ Neff 1987, str. 63.

- ^ A b Gough (1961) str. 342.

- ^ "The Hindu Goddess Kali". LACMA sbírky. Citováno 3. ledna 2019.

- ^ Panikkar (1918) str. 279–280

- ^ Panikkar (1918) str. 279-281

- ^ Panikkar (1918) str. 282–283

- ^ A b C Panikkar (1918) str. 272–275.

- ^ A b Panikkar (1918) str. 275–276.

- ^ Freeland, J. B. (1965). "The Nayar of Central Kerala". Články v antropologii: 12.

- ^ A b Osella, Filippo; Osella, Caroline (2000). Social mobility in Kerala: modernity and identity in conflict. Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0-7453-1693-2. Citováno 5. června 2011.

- ^ Kurien, Prema A. (2002). Kaleidoscopic ethnicity: international migration and the reconstruction of community identities in India. Rutgers University Press. str. 124–. ISBN 978-0-8135-3089-5. Citováno 5. června 2011.

- ^ A b C d Gough (1961), pp. 307–308

- ^ A b C Panikkar 257–258

- ^ Gough (1961), str. 310

- ^ A b C Nossiter (1982) s. 25–27

- ^ Gough (1961), str. 306

- ^ Gough (1961), str. 309–311

- ^ Kodoth, Praveena (2008). "Gender, Caste and Matchmaking in Kerala: A Rationale for Dowry". Rozvoj a změna. Institute of Social Studies. 39 (2): 263–283. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.2008.00479.x.(vyžadováno předplatné)

- ^ Fuller (1975) 299–301

- ^ Menon, Dilip M. (August 1993). "The Moral Community of the Teyyattam: Popular Culture in Late Colonial Malabar". Studie z historie. 9 (2): 187–217. doi:10.1177/025764309300900203. S2CID 161804169.(vyžadováno předplatné)

- ^ Rajendra Kumar Sharma (1 January 2004). Venkovská sociologie. Atlantic Publishers & Dist. str. 150. ISBN 978-81-7156-671-6. Citováno 23. května 2011.

- ^ A b Fuller (1975) 286–289

- ^ Fuller (1975) Reproduced from p. 288

- ^ Srinivas, Mysore Narasimhachar (Srpen 1957). "Caste in Modern India". The Journal of Asian Studies. Sdružení pro asijská studia. 16 (4): 529–548. doi:10.2307/2941637. JSTOR 2941637.(vyžadováno předplatné)

- ^ Srinivas, Mysore Narasimhachar (1995) [1966]. Social change in modern India (Rabindranath Tagore memorial lectures). Orient Blackswan. str. 38. ISBN 978-81-250-0422-6.

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 290.

- ^ Fuller (1975) pp. 289–291.

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 294.

- ^ Fuller (1975) pp. 291–292, 305

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 303

- ^ Fuller (1975) pp. 293–295, 298

- ^ Devika, J.; Varghese, V. J. (March 2010). To Survive or to flourish? Minority rights and Syrian Christian assertions in 20th century Travancore (PDF). Trivandrum: Centre for Development Studies. s. 15–17. Archivovány od originál (PDF) dne 26. května 2012. Citováno 28. dubna 2012.

- ^ A b Fuller (1975) 303–304.

- ^ A b C Nossiter (1982) str. 29

- ^ "List of Other Backward Communities". District of Thiruvananthapuram. Archivovány od originál dne 22. března 2012. Citováno 12. června 2011.

- ^ A b Panikkar (1918) pp. 260–264

- ^ A b Nakane, Chie (1962). "The Nayar family in a disintegrating matrilineal system". International Journal of Comparative Sociology (Reprinted (in Family and Marriage, International Studies in Sociology and Social Anthropology: 1963: E. J. Brill, Leiden, Netherlands) ed.). 3 (1): 17–28. doi:10.1177/002071526200300105. S2CID 220876041.

- ^ A b Fuller (1975) str. 283

- ^ Ghosh, Amitav (2003). Imám a Ind: prózy (Třetí vydání.). Orient Blackswan. str. 193. ISBN 978-81-7530-047-7. Citováno 27. prosince 2011.

- ^ Fuller (1975) pp. 284, 297

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 297

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 298

- ^ Moore, Melinda A. (September 1985). "A New Look at the Nayar Taravad". Muž. Nová série. 20 (3): 523–541. doi:10.2307/2802444. JSTOR 2802444.(vyžadováno předplatné)

- ^ A b Moore, Melinda A. (May 1988). "Symbol and meaning in Nayar marriage ritual". Americký etnolog. 15 (2): 254–273. doi:10.1525/ae.1988.15.2.02a00040. JSTOR 644756.(vyžadováno předplatné)

- ^ Nossiter (1982) str. 27

- ^ A b C d Fuller (1975) str. 296

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 302

- ^ Fuller (1975) 299–300

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 300

- ^ A b Fuller (1975) pp. 295, 298

- ^ Panikkar (1918) 267–270

- ^ Gough (1961), str. 355–356

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 301

- ^ Fuller (1975) 302–303

- ^ A b C Panikkar (1918) 270–271

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 296–297

- ^ Gough (1961), str. 320

- ^ Panikkar (1918) str. 265.

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 292–293, 302

- ^ Fuller (1975) 284–285

- ^ A b Gough, Kathleen (leden – únor 1965). "Poznámka o Nayarském manželství". Muž. Královský antropologický institut Velké Británie a Irska. 65: 8–11. doi:10.2307/2796033. JSTOR 2796033.

- ^ Levine, Nancy E .; Sangree, Walter H. (1980). „Závěr: Asijské a africké systémy polyandrie“. Journal of Comparative Family Studies. XI (3): 399.Citace: Podstatou systému Nayar bylo, že stejně jako žena byla zapojena do manželských vztahů s řadou mužů, muž byl ženatý s řadou žen. Nayarské ženy a jejich manželé tradičně nežili společně ve stejné domácnosti. Manželé byli povinni dávat svým manželkám určité dary ve stanovených časech, ale jejich vztah měl malý význam kromě sexuálního styku a zajištění legitimity dětem produkovaným v manželství. Vzhledem k tomu, že tito muži bydleli odděleně a nebyli žádným způsobem hodnoceni, nelze Nayarovo manželství charakterizovat hierarchií charakteristickou pro přidružené manželství nebo solidaritou bratrské polyandrie. Na rozdíl od bratrských a přidružených systémů také muži, kteří navštívili jednu ženu, nemohli být bratři, ani muž nemohl mít sexuální vztahy se dvěma ženami ve stejné domácnosti. To znamená, že bratrská polyandrie a sororální polygynie byly zakázány.

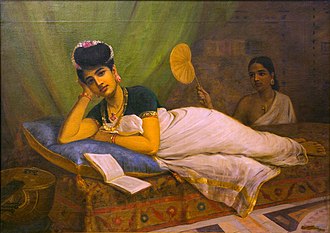

- ^ A b Dinkar, Niharika (11. dubna 2014). „Soukromé životy a interiéry: Obrazy učenců Raja Ravi Varmy“. Historie umění. Wiley. 37 (3): 10. doi:10.1111/1467-8365.12085. ISSN 0141-6790.

- ^ Sen, G. (2002). Ženské bajky: zobrazování indické ženy v malbě, fotografii a kině. Mapin Publishing. str. 76. ISBN 978-81-85822-88-4. Citováno 9. července 2018.

- ^ Fuller (1976) p128

- ^ Arunima 1995, str. 161-162.

- ^ Fuller (1975) str. 285

- ^ Nayar, V. K. S. (1967). „Kerala Politics since 1947: Community Attitudes“. V Narain, Iqbal (ed.). Státní politika v Indii. 1965. str. 153.

- ^ A b Devika, J .; Varghese, V. J. (březen 2010). Přežít nebo vzkvétat? Práva menšin a tvrzení syrských křesťanů v Travancore 20. století (PDF). Trivandrum: Centrum pro rozvojová studia. str. 19–20. Archivovány od originál (PDF) dne 26. května 2012. Citováno 27. dubna 2012.

Bibliografie

- Ashley, Wayne (1979). „Teyyam Kettu ze severní Keraly“. Dramatická recenze: TDR. JSTOR. 23 (2): 99–112. doi:10.2307/1145219. ISSN 0012-5962. JSTOR 1145219.

- Menon, A.S. (2011). Historie Kerala a její tvůrci. Knihy DC. ISBN 978-81-264-3782-5. Citováno 1. ledna 2019.

- Jeffrey, R. (2016). Politika, ženy a pohoda: Jak se Kerala stala „modelkou“. Cambridge Commonwealth Series. Palgrave Macmillan UK. ISBN 978-1-349-12252-3. Citováno 1. ledna 2019.

- Almeida, H. (2017). Indická renesance: Britské romantické umění a vyhlídka na Indii. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-351-56296-6. Citováno 31. prosince 2018.

- Bock, M .; Rao, A. (2000). Kultura, stvoření a plodení: Pojmy příbuznosti v jihoasijské praxi. E-kniha humanitních věd ACLS. Berghahn Books. ISBN 978-1-57181-911-6. Citováno 31. prosince 2018.

- Blankenhorn, D. (2007). Budoucnost manželství. Encounter Books. str.106. ISBN 978-1-59403-359-9. Citováno 1. ledna 2019.

- Arunima, G. (2003). There Comes Papa: Colonialism and the Transformation of Matriliny in Kerala, Malabar, C. 1850-1940. Orient BlackSwan. ISBN 978-81-250-2514-6. Citováno 30. června 2018.

- Arunima, G. (1995). "Matriliny a její nespokojenosti". Indie International Center Quarterly. 22 (2/3): 157–167. JSTOR 23003943. JSTOR.

- Plešatý, V .; Chatterji, M .; Reddy, S .; Prashad, V .; Vimalassery, M. (2013). Slunce nikdy nezapadá: jihoasijští migranti ve věku americké moci. Série NYU v sociální a kulturní analýze. NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-8644-4. Citováno 20. prosince 2018.

- Fawcett, F. (2004) [1901]. Nâyars z Malabar. Asijské vzdělávací služby. ISBN 978-81-206-0171-0.

- Fuller, Christopher John (Zima 1975). "Vnitřní struktura Nayarské kasty". Journal of Anthropological Research. 31 (4): 283–312. doi:10.1086 / jar.31.4.3629883. JSTOR 3629883. S2CID 163592798.(vyžadováno předplatné)

- Fuller, Christopher John (1976). Nayars dnes. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29091-3.

- Clark-Deces, I. (2011). Společník antropologie Indie. Wiley Blackwell Companions to Anthropology. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-4443-9058-2. Citováno 7. ledna 2019.

- Gopinath, G. (2018). Unruly Visions: The Esthetic Practices of Queer Diaspora. Perverse Modernities: A Series Edited by Jack Halberstam and Lisa Lowe. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-0216-1. Citováno 20. prosince 2018.

- Jacobsen, K.A. (2015). Routledge Handbook of Contemporary India. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-317-40357-9. Citováno 20. prosince 2018.

- Lukose, R.A. (2009). Děti liberalizace: Gender, mládež a občanství spotřebitelů v globalizující se Indii. Odborná sbírka knih e-Duke. Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-9124-1. Citováno 20. prosince 2018.

- Goody, J. (1975). Gramotnost v tradičních společnostech. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29005-0. Citováno 7. ledna 2019.

- Gough, E. Kathleen (1961), „Nayars: Central Kerala“ „Schneider, David Murray; Gough, E. Kathleen (eds.), Matrilineální příbuzenství, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-02529-5, vyvoláno 9. června 2011

- Massey, R. (2004). Indické tance: jejich historie, technika a repertoár. Publikace Abhinav. ISBN 978-81-7017-434-9. Citováno 22. prosince 2018.

- Narayanan, M. T. (2003), Agrární vztahy v pozdně středověkém malabaru, Northern Book Center, ISBN 978-81-7211-135-9

- Neff, Deborah L. (1987). "Estetika a síla v Pambinu Tullal: posedlý rituál venkovské keraly". Etnologie. JSTOR. 26 (1): 63–71. doi:10.2307/3773417. ISSN 0014-1828. JSTOR 3773417.

- Nossiter, Thomas Johnson (1982). „Keralina identita: jednota a rozmanitost“. Komunismus v Kérale: studie politické adaptace. University of California Press. s. 12–44. ISBN 978-0-520-04667-2. Citováno 9. června 2011.

- Panikkar, Kavalam Madhava (Červenec – prosinec 1918). „Některé aspekty života Nayar“. Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 48: 254–293. Citováno 9. června 2011.

- Mukherjee, M. (2002). Rané romány v Indii. Sahitya Akademi. ISBN 978-81-260-1342-5. Citováno 7. ledna 2019.

- Sarkar, S. (2014). Moderní Indie 1886-1947. Pearson Indie. ISBN 978-93-325-4085-9. Citováno 7. ledna 2019.

- Stone, L .; King, D.E. (2018). Příbuzenství a pohlaví: Úvod. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-429-87165-8. Citováno 22. prosince 2018.

- Thomas, S. (2018). Privilegované menšiny: syrské křesťanství, pohlaví a práva menšin v postkoloniální Indii. University of Washington Press. ISBN 978-0-295-74383-7. Citováno 20. prosince 2018.

- Vickery, M. (1998). Společnost, ekonomika a politika v Kambodži před Angkorem: 7. – 8. Století. Centrum východoasijských kulturních studií pro Unesco, Toyo Bunko. ISBN 978-4-89656-110-4. Citováno 22. prosince 2018.

- Wade, Bonnie C .; Jones, Betty True; Zile, Judy Van; Higgins, Jon B .; Qureshi, Regula Burckhardt; Owens, Naomi; Flora, Reis (1987). „Divadlo v Indii: Eseje o hudbě, tanci a dramatu“. Asijská hudba. JSTOR. 18 (2): 1. doi:10.2307/833942. ISSN 0044-9202. JSTOR 833942.

- Jeffrey, Robin (1994) [1976]. Úpadek dominance Nair: Společnost a politika v Travancore 1847–1908. Sussex University Press. ISBN 978-0-85621-054-9.

- Zarrilli, P. (2003). Kathakali Dance-Drama: Where Gods and Demons Come to play. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-134-65110-8. Citováno 2. ledna 2019.

- Zarrilli, P. (1984). Komplex Kathakali: herec, výkon a struktura. Publikace Abhinav. ISBN 978-81-7017-187-4. Citováno 7. ledna 2019.

externí odkazy

- „Digitální koloniální dokumenty (Indie)“. Archivovány od originál dne 1. září 2007.