Hans Kelsen - Hans Kelsen

Hans Kelsen | |

|---|---|

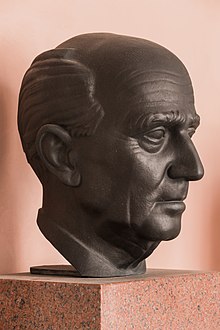

Hans Kelsen (č. 17) - Busta v Arkadenhofu, Vídeňská univerzita | |

| narozený | 11. října 1881 |

| Zemřel | 19.dubna 1973 (ve věku 91) |

| Vzdělávání | Vídeňská univerzita (Dr. juris, 1906; habilitace, 1911) |

| Éra | Filozofie 20. století |

| Kraj | Západní filozofie |

| Škola | Právní pozitivismus |

| Instituce | University of California, Berkeley |

| Teze | Hauptprobleme der Staatsrechtslehre entwickelt aus der Lehre vom Rechtssatze (Hlavní problémy v teorii veřejného práva, vyvinuté z teorie právního prohlášení (1911) |

| Doktorandi | Eric Voegelin[1] Alfred Schütz |

Hlavní zájmy | Filozofie práva |

Pozoruhodné nápady | Čistá teorie práva (neo-Kantian normativní základy právní systémy ) Základní norma |

Vlivy | |

Hans Kelsen (/ˈkɛls.n/; Němec: [ˈHans ˈkɛlsən]; 11.10.1881 - 19.4.1973) byl Rakušan právník, právní filozof a politický filozof. Byl autorem roku 1920 Rakouská ústava, což do značné míry platí dodnes. Kvůli vzestupu totality v Rakousku (a ústavní změně z roku 1929)[2] Kelsen odešel do Německa v roce 1930, ale byl nucen opustit tento univerzitní post po Hitlerově uchopení moci v roce 1933 kvůli jeho židovskému původu. Ten rok odešel do Ženevy a později se přestěhoval do Spojených států v roce 1940. V roce 1934 Roscoe Libra chválil Kelsena jako „nepochybně předního právníka té doby“. Zatímco ve Vídni, Kelsen setkal Sigmund Freud a jeho kruhu a psal na téma sociální psychologie a sociologie.

Ve 40. letech byla Kelsenova reputace ve Spojených státech již dobře zavedena pro svou obranu demokracie i pro svou Čistá teorie práva. Kelsenovo akademické postavení přesahovalo samotnou právní teorii a rozšířilo se na politická filozofie a sociální teorie stejně. Jeho vliv zahrnoval oblasti filozofie, právní vědy, sociologie, teorie demokracie a Mezinárodní vztahy.

Pozdní v jeho kariéře, zatímco u University of California, Berkeley, ačkoli Kelsen oficiálně odešel do důchodu v roce 1952, přepsal svou krátkou knihu z roku 1934, Reine Rechtslehre (Čistá teorie práva), do mnohem rozšířeného „druhého vydání“ vydaného v roce 1960 (v anglickém překladu vyšlo v roce 1967). Kelsen po celou dobu své aktivní kariéry významně přispíval k teorii soudního přezkumu, hierarchické a dynamické teorii pozitivního práva a vědě o právu. V politické filozofii byl obhájcem státněprávní teorie identity a zastáncem výslovného kontrastu témat centralizace a decentralizace v teorii vlády. Kelsen byl také zastáncem pozice oddělení konceptů státu a společnosti v souvislosti se studiem právní vědy.

Přijetí a kritika Kelsenovy práce a příspěvků byla rozsáhlá jak u horlivých příznivců, tak u kritiků. Kelsenovy příspěvky k právní teorii norimberských procesů byly podporovány a zpochybňovány různými autory, včetně Dinsteina na Hebrejské univerzitě v Jeruzalémě. Kelsen neo-Kantian obrana kontinentu právní pozitivismus byl podpořen uživatelem H. L. A. Hart v jeho kontrastní formě anglo-amerického právního pozitivismu, o kterém ve své anglo-americké formě debatovali vědci jako např. Ronald Dworkin a Jeremy Waldron.

Životopis

Kelsen se narodil v roce Praha do německé střední třídy, židovský rodina. Jeho otec, Adolf Kelsen, byl z Galicie a jeho matka, Auguste Löwy, byla z Čechy. Hans byl jejich první dítě; budou tam dva mladší bratři a sestra. Rodina se přestěhovala do Vídeň v roce 1884, kdy byly Hansovi tři roky. Po absolvování Akademisches Gymnasium Studoval Kelsen zákon na Vídeňská univerzita, který získal doktorát z práva (Dr. juris ) dne 18. května 1906 a jeho habilitace dne 9. března 1911. Dvakrát v životě Kelsen konvertoval k samostatným náboženským denominacím. V době své disertační práce o Danteovi a katolicismu byl Kelsen pokřtěn jako římský katolík dne 10. června 1905. Dne 25. května 1912 se oženil s Margarete Bondi (1890–1973), přičemž tito dva konvertovali o několik dní dříve na luteránství Augsburské vyznání; měli by dvě dcery.[3]

Kelsen a jeho léta v Rakousku do roku 1930

Kelsenova disertační práce o Danteho teorii státu v roce 1905 se stala jeho první knihou o politické teorii.[4] V této knize Kelsen výslovně upřednostňoval čtení knihy Dante Alighieri je Božská komedie jak do značné míry vychází z politické alegorie. Studie pečlivě zkoumá „doktrínu dvou mečů“ z Papež Gelasius I., spolu s Danteovými výraznými náladami v římskokatolických debatách mezi Guelfové a ghibelliny.[5] Kelsenova konverze na katolicismus byla současná až do dokončení knihy v roce 1905. V roce 1908 získal Kelsen vědecké stipendium, které mu umožnilo zúčastnit se University of Heidelberg po tři po sobě jdoucí semestry, kde studoval u významného právníka Georg Jellinek před návratem do Vídně.

Závěrečná kapitola Kelsenovy studie politické alegorie v Dante byla také důležitá pro zdůraznění konkrétní historické cesty, která vedla přímo k vývoji moderního práva ve dvacátém století. Poté, co zdůraznil Danteův význam pro tento vývoj právní teorie, Kelsen poté naznačil historický význam Niccolò Machiavelli a Jean Bodin k těmto historickým přechodům v právní teorii vedoucí k modernímu právu dvacátého století.[6] V případě Machiavelliho viděl Kelsen důležitý protiklad přehnané výkonné části vlády fungující bez účinných právních omezení odpovědného chování. Pro Kelsena by to pomohlo při orientaci jeho vlastního právního myšlení ve směru silné vlády právního státu, se zvýšeným důrazem na ústřední význam plně propracované pravomoci soudního přezkumu.[6]

Kelsenův čas v Heidelbergu měl pro něj trvalý význam v tom, že začal upevňovat své postavení identity práva a státu od počátečních kroků, které podle jeho názoru Jellinek podnikl. Kelsenova historická realita měla být obklopena dualistickými teoriemi práva a státu převládajícími v jeho době. Hlavní otázka pro Jellinek a Kelsen, jak uvedl Baume[7] je: „Jak lze sladit nezávislost státu v dualistické perspektivě s jeho statusem (jako) představitele právního řádu? Pro dualistické teoretiky zůstává alternativa k monistickým doktrínám: teorie sebeomezení státu. Georg Jellinek je významným představitelem této teorie, která umožňuje vyhnout se redukci státu na právní subjekt a také vysvětlit pozitivní vztah mezi právem a státem. Sebeomezení sféry státu předpokládá, že stát, jako svrchovaná moc se z mezí, které si sama stanoví, stává právním státem. ““[7] Pro Kelsena to bylo vhodné, pokud to šlo, ale stále to bylo dualistická doktrína, a proto ji Kelsen odmítl s uvedením: „Problém takzvané auto-povinnosti státu je jedním z těch pseudoproblémů, které vyplývají z chybný dualismus státu a práva. Tento dualismus je zase způsoben omylem, jehož se v historii všech oblastí lidského myšlení setkáváme s četnými příklady. Naše touha po intuitivní reprezentaci abstrakcí nás vede k zosobnění jednoty systém a poté hypostazovat personifikaci. To, co původně představovalo pouze způsob reprezentace jednoty systému objektů, se stává novým objektem, který existuje sám o sobě. “[8] Kelsen se k této kritice přidal význačný francouzský právník Léon Duguit, který napsal v roce 1911: „Teorie sebeomezení (vis Jellinek) obsahuje skutečný klam. Dobrovolná podřízenost není podřízenost. Stát není ve skutečnosti omezen zákonem, pokud tento zákon může zavést a napsat sám stát, a pokud může kdykoli provést jakékoli změny, které v něm chce provést. Tento druh základů veřejného práva je zjevně mimořádně křehký. “[9] Výsledkem bylo, že Kelsen upevnil svůj postoj a podpořil doktrínu identity práva a státu.[10]

V roce 1911 dosáhl svého habilitace (licence k přednáškám na univerzitě) v veřejné právo a právní filozofie, s prací, která se stala jeho prvním významným dílem o právní teorii, Hauptprobleme der Staatsrechtslehre entwickelt aus der Lehre vom Rechtssatze („Hlavní problémy v teorii veřejného práva, vycházející z teorie právního prohlášení“).[11] V roce 1919 se stal plným profesor veřejnosti a správní právo na vídeňské univerzitě, kde založil a upravil Zeitschrift für öffentliches Recht (Journal of Public Law). Na příkaz kancléře Karl Renner, Kelsen pracoval na přípravě nového Rakouská ústava, přijatý v roce 1920. Dokument stále tvoří základ rakouského ústavního práva. Kelsen byl jmenován do Ústavního soudu na celý svůj život. Kelsenův důraz v těchto letech na kontinentální formu právního pozitivismu začal dále vzkvétat z hlediska jeho právně-státního monismu, poněkud založeného na předchozích příkladech kontinentálního právního pozitivismu nalezených u takových učenců dualismu právního státu, jako je Paul Laband ( 1838–1918) a Carl Friedrich von Gerber (1823–1891).[12]

Na počátku 20. let 20. století vydal šest hlavních děl z oblasti vlády, veřejné právo, a mezinárodní zákon: v roce 1920, Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts (Problém svrchovanosti a teorie mezinárodního práva)[13] a Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie (O podstatě a hodnotě demokracie);[14] v roce 1922, Der soziologische und der juristische Staatsbegriff (Sociologické a právnické koncepce státu);[15] v roce 1923, Österreichisches Staatsrecht (Rakouské veřejné právo);[16] a v roce 1925 Allgemeine Staatslehre (Obecná teorie státu),[17][18] dohromady s Das Problem des Parlamentarismus (Problém parlamentarismu). Na konci 20. let po nich následovala Die philosophischen Grundlagen der Naturrechtslehre und des Rechtspositivismus (Filozofické základy nauky o přirozeném právu a právním pozitivismu).[19]

Ve 20. letech 20. století Kelsen pokračoval v prosazování své slavné teorie identity práva a státu, díky níž bylo jeho úsilí kontrapunktem k postavení Carl Schmitt který prosazoval prioritu politických zájmů státu. Kelsena ve své pozici podpořili Adolf Merkl a Alfred Verdross, zatímco proti jeho názoru se vyjádřili Erich Kaufman, Hermann Heller a Rudolf Smend.[20] Důležitou součástí Kelsenova hlavního praktického odkazu je vynálezce moderního evropského modelu ústavní kontrola. Poprvé byl představen v Rakousku a Československu v roce 1920,[21] a později v Spolková republika Německo, Itálie, Španělsko, Portugalsko, stejně jako v mnoha zemích střední a východní Evropy.

Jak bylo popsáno výše, model Kelsenianského soudu vytvořil samostatný ústavní soud, který měl nést výlučnou odpovědnost za ústavní spory v soudním systému. Kelsen byl hlavním autorem jejích stanov v rakouské ústavě, jak dokumentuje ve své výše citované knize z roku 1923. To se liší od systému obvyklého v zvykové právo země, včetně Spojených států, v nichž mají soudy obecné jurisdikce od soudního procesu až po soud poslední instance často pravomoc k ústavnímu přezkumu. V návaznosti na rostoucí politickou polemiku o některých pozicích rakouského Ústavního soudu čelil Kelsen rostoucímu tlaku ze strany správy, která ho jmenovala, aby se konkrétně zabýval otázkami a případy týkajícími se zajištění ustanovení o rozvodu ve státním rodinném právu. Kelsen inklinoval k liberálnímu výkladu ustanovení o rozvodu, zatímco administrativa, která ho původně jmenovala, reagovala na tlak veřejnosti, aby převážně katolická země zaujala konzervativnější postoj k otázce omezování rozvodu. V tomto stále konzervativnějším klimatu Kelsen, který byl považován za sympatizující s Sociální demokraté, i když není členem strany, byl ze soudu odstraněn v roce 1930.

Kelsen a jeho evropské roky mezi lety 1930 a 1940

Ve své nedávné knize o Kelsenu Sandrine Baume[22] shrnul konfrontaci mezi Kelsenem a Schmittem na samém počátku 30. let. Tato debata měla znovu nastartovat Kelsenovu silnou obranu zásady soudního přezkumu proti zásadě autoritářské verze výkonné moci, kterou si Schmitt představoval pro národní socialismus v Německu. Kelsen napsal svou ostrou odpověď Schmittovi ve své eseji z roku 1931 „Kdo by měl být strážcem ústavy?“, Ve které jasně hájil důležitost soudního přezkumu nad a proti nadměrné formě výkonné autoritářské vlády, kterou Schmitt vyhlašoval na počátku 30. let. Jak uvádí Baume, „Kelsen hájil legitimitu ústavního soudu bojem proti důvodům, které Schmitt uvádí pro přiřazení role strážce ústavy prezidentovi říše. Spor mezi těmito dvěma právníky byl o tom, který orgán státu by měl mít roli strážce německé ústavy. Kelsen si myslel, že tato mise by měla být svěřena soudnictví, zejména Ústavnímu soudu. “[22] Ačkoli Kelsen byl úspěšný při přípravě oddílů ústavy v Rakousku pro silný soudní přezkum,[23] jeho sympatizanti v Německu byli méně úspěšní. Oba Heinrich Triepel v roce 1924 a Gerhard Anschütz v roce 1926 byli neúspěšní ve své výslovné snaze vštípit silnou verzi soudního přezkumu německé Weimarské ústavě.[24]

Kelsen přijal profesuru na Univerzita v Kolíně nad Rýnem v roce 1930. Když se k moci dostali národní socialisté Německo v roce 1933 byl ze své funkce odvolán. Přesídlil do Ženeva, Švýcarsko kde učil mezinárodní právo na Postgraduální institut mezinárodních studií od roku 1934 do roku 1940. Během tohoto časového období Hans Morgenthau odešel z Německa, aby dokončil habilitační práci v Ženevě, která vyústila v jeho knihu Realita norem a zejména norem mezinárodního práva: Základy teorie norem.[25] Díky pozoruhodnému štěstí pro Morgenthau Kelsen právě dorazil do Ženevy jako profesor a stal se poradcem pro Morgenthauovu disertační práci. Kelsen byl jedním z nejsilnějších kritiků Carl Schmitt protože Schmitt se zasazoval o prioritu politických zájmů státu před tím, jak se stát drží právní stát. Kelsen a Morgenthau byli sjednoceni proti této nacionálně socialistické škole politické interpretace, která oslabila právní stát, a stali se celoživotními kolegy, i když oba emigrovali z Evropy, aby zaujali příslušné akademické pozice ve Spojených státech. Během těchto let se Kelsen i Morgenthau oba stali persona non grata v Německu během plného nástupu moci nacionálního socialismu.

Že Kelsen byl hlavním obhájcem Morgenthau Habilitační šichta je nedávno dokumentován v překladu Morgenthauovy knihy s názvem Koncept politického.[26] V úvodní eseji svazku Behr a Rosch naznačují, že ženevská fakulta pod zkoušejícími Waltherem Burckhardtem a Paul Guggenheim byly zpočátku docela negativní ohledně Morgenthauových Habilitační šichta. Když Morgenthau našel pařížského vydavatele svazku, požádal Kelsena, aby jej přehodnotil. Podle slov Behra a Roscha „Kelsen byl správnou volbou pro posouzení Morgenthauovy práce, protože nejenže byl vyšším vědcem v Staatslehre, ale Morgenthauova teze byla také do značné míry kritickým zkoumáním Kelsenova právního pozitivismu. Byl to tedy Kelsen, kterému Morgenthau 'dlužil Habilitace v Ženevě, “jako Kelsenův autor životopisů Rudolf Aladár Métall[27][28] potvrzuje, a také nakonec jeho následná akademická kariéra, protože Kelsen vytvořil pozitivní hodnocení, které přesvědčilo zkušební komisi, aby Morgenthauovi udělil jeho Habilitace."[29]

V roce 1934, ve věku 52, vydal první vydání Reine Rechtslehre (Čistá teorie práva ).[30] Zatímco v Ženevě se o něj začal hlouběji zajímat mezinárodní zákon. Tento zájem o mezinárodní právo v Kelsenu byl z velké části reakcí na Pakt Kellogg – Briand v roce 1929 a jeho negativní reakce na obrovský idealismus, který viděl na svých stránkách, spolu s nedostatečným uznáním sankcí za nezákonné akce válčících států. Kelsen přišel silně podpořit teorii zákona o sankcích a deliktech, kterou považoval za podstatně nedostatečně zastoupenou v paktu Kellogg-Briand. V letech 1936–1938 byl krátce profesorem na Německá univerzita v Praze před návratem do Ženevy, kde zůstal až do roku 1940. Jeho zájem o mezinárodní právo by se zvláště zaměřil na Kelsenovy spisy o mezinárodních válečných zločinech, které by po svém odchodu do Spojených států zdvojnásobil své úsilí.

Hans Kelsen a jeho americké roky po roce 1940

V roce 1940, ve věku 58 let, on a jeho rodina uprchli z Evropy na poslední plavbu SS Washington, nastupující 1. června v Lisabon. Přestěhoval se do Spojené státy, což prestižní Přednášky Olivera Wendella Holmese na Harvardská právnická škola v roce 1942. Byl podporován Roscoem Poundem na pozici fakulty na Harvardu, ale na rozdíl od Lona Fullera na Harvardské fakultě, než se stal řádným profesorem na katedře politická věda na University of California, Berkeley v roce 1945. Kelsen hájil pozici rozdílu filosofické definice spravedlnosti, protože je oddělitelná od aplikace pozitivního práva. Fuller uvedl svůj nesouhlas: „Sdílím názor Jerome Halla, který je doložen tímto vynikajícím Čtení, že jurisprudence by měla vycházet ze spravedlnosti. Tuto preferenci nekladu na exhortační důvody, ale na víru, že dokud člověk nebude zápasit s problémem spravedlnosti, nemůže skutečně pochopit ostatní otázky jurisprudence. Kelsen například vylučuje spravedlnost ze svých studií (praktického práva), protože je „iracionálním ideálem“, a proto „nepodléhá poznání“. Celá struktura jeho teorie pochází z tohoto vyloučení. Význam jeho teorie lze tedy pochopit pouze tehdy, když jsme podrobili kritickému zkoumání její základní kámen negace. “[31] Lon Fuller cítil, že přirozeně právní postavení, které obhajoval proti Kelsenovi, je neslučitelné s Kelsenovým odhodláním odpovědného používání pozitivního práva a vědy o právu. V následujících letech se Kelsen stále více zabýval otázkami mezinárodní zákon a mezinárodní instituce, jako je Spojené národy. V letech 1953-54 byl hostující profesor mezinárodního práva na United States Naval War College.

Jak poznamenal, další část Kelsenova praktického odkazu,[32] měl vliv jeho spisy z 30. a počátku 40. let na rozsáhlé a bezprecedentní stíhání politických vůdců a vojenských vůdců na konci druhé světové války v Norimberku a Tokiu, které vedlo k přesvědčení ve více než tisíci případech válečných zločinů. Pro Kelsena byly pokusy vyvrcholením přibližně patnácti let výzkumu, kterému se věnoval tomuto tématu, který začal ještě v jeho evropských letech a na který navázal slavnou esejí „Will the Judgment In the Nuremberg Trial Constitution a Precedent In Mezinárodní právo ?, “publikováno v Čtvrtletní mezinárodní právo v roce 1947. Předcházela jí v roce 1943 Kelsenova esej „Kolektivní a individuální odpovědnost v mezinárodním právu se zvláštním zřetelem na trestání válečných zločinců“, 31 California Law Review, s. 530, a v roce 1944 jeho esejí „Pravidlo proti ex post facto a stíhání válečných zločinců Osy“, která vyšla v Soudce Advokát Journal, Vydání 8.

V eseji Kelsena z roku 1948 pro J.Y.B.I.L. k jeho eseji „War Criminals“ z roku 1943 citované v předchozím odstavci nazvaném „Kolektivní a individuální odpovědnost za státní činy v mezinárodním právu“[33] Kelsen představil své myšlenky na rozdíl mezi naukou o respondeat superior a akty státní doktríny, pokud jsou použity jako obrana během stíhání válečných zločinů. Na straně 228 eseje Kelsen uvádí, že „akty státu jsou akty jednotlivců, které vykonávají jako orgány státu, zejména orgánem, který se nazývá vláda z stát. Tyto činy provádějí jednotlivci, kteří patří k vládě jako hlava státu, nebo členové kabinetu, nebo jsou činy prováděné na její příkaz nebo se souhlasem vlády“Yoram Dinstein z Hebrejské univerzity v Jeruzalémě přijal ve své knize výjimku z Kelsenovy formulace Obrana „poslušnosti vyšších řádů“ v mezinárodním právu, dotisknutý v roce 2012 Oxford University Press, zabývající se specifickým přisuzováním Kelsenových aktů státu.[34]

Krátce po zahájení přípravy Charty OSN dne 25. dubna 1945 v San Francisku začal Kelsen psát své rozšířené 700stránkové pojednání o OSN jako nově jmenovaný profesor na Kalifornské univerzitě v Berkeley (Zákon Organizace spojených národů, New York 1950). V roce 1952 také publikoval svou knižní studii o mezinárodním právu s názvem Zásady mezinárodního práva v angličtině a dotisk v roce 1966. V roce 1955 se Kelsen obrátil na 100stránkovou esej „Foundations of Democracy“ pro přední filozofický časopis Etika; psaný během vrcholícího napětí studené války, vyjadřoval vášnivý závazek k západnímu modelu demokracie nad sovětskými a nacionálně socialistickými formami vlády.[35]

Tato esej Kelsena o demokracii z roku 1955 byla také důležitá pro shrnutí jeho kritického postoje ke knize o politice od roku 1954, kterou napsal jeho bývalý student v Evropě Eric Voegelin. Poté v knize s názvem Kelsen Nová věda o politice (Ontos Verlag, dotisk v roce 2005, 140pp, původně publikováno v roce 1956), Kelsen vyjmenoval bod po bodu kritiku nadměrného idealismu a ideologie, kterou považoval za převládající ve Voegelinově knize o politice. Tato výměna a debata byla dokumentována v dodatku ke knize, který napsal autor na Voegelinovi Barry Cooper, nazvaný Voegelin a základy moderní politické vědy z roku 1999. Další Kelsenova kniha obhajující jeho realistické stanovisko k otázce oddělení státu a náboženství na rozdíl od postoje Voegelina k této otázce byla vydána posmrtně pod názvem Sekulární náboženství. Kelsenovým cílem bylo zčásti zajistit důležitost odpovědného oddělení státu a náboženství pro ty, kdo mají sympatie k náboženství a mají zájem o toto oddělení. Po Kelsenově knize z roku 1956 následovala v roce 1957 sbírka esejů o spravedlnosti, právu a politice, většina z nich byla dříve publikována v angličtině.[36] Původně vyšlo v německém jazyce v roce 1953.

Čistá teorie práva

Kelsen je považován za jednoho z nejvýznamnějších právníků 20. století a byl mezi vědci velmi vlivný jurisprudence a veřejné právo, zejména v Evropě a Latinské Americe, i když v zemích obecného práva méně. Jeho kniha s názvem Čistá teorie práva (Němec: Reine Rechtslehre) byl vydán ve dvou vydáních, jedno v Evropě v roce 1934, a druhé rozšířené vydání poté, co v roce 1960 nastoupil na fakultu University of California v Berkeley.

Kelsen Čistá teorie práva je široce uznáván jako jeho opus magnum. Jejím cílem je popsat právo jako hierarchii norem, které jsou rovněž závaznými normami, a zároveň tyto normy sám odmítá hodnotit. To znamená, že „právní věda“ má být oddělena od „právní politiky“. Centrální vůči Čistá teorie práva je pojem „základní normy (Grundnorm ) '- hypotetická norma předpokládaná teorií, ze které v hierarchii všechny „nižší“ normy v legální systém, počínaje ústavní právo se rozumí, že odvozují svoji autoritu nebo „závaznost“. Tímto způsobem Kelsen tvrdí, že závaznost právních norem, jejich specificky „právní“ charakter, lze chápat, aniž by byla nakonec sledována k nějakému nadlidskému zdroji, jako je Bůh, zosobněná příroda nebo zosobněný stát nebo národ.[37]

The Čistá teorie práva je obecně považován za jeden z nejoriginálnějších příspěvků Hanse Kelsena k právní teorii. Jeho kniha s tímto názvem byla poprvé vydána v roce 1934 a ve velmi rozšířeném druhém vydání (ve skutečnosti a magnum opus zdvojnásobení délky prezentace) v roce 1960. Druhé vydání vyšlo v anglickém překladu v roce 1967, as Čistá teorie práva;[38] první vydání se objevilo v anglickém překladu v roce 1992, as Úvod do problematiky právní teorie. Teorie navrhovaná v této knize byla pravděpodobně nejvlivnější teorií práva vytvořenou během 20. století. Je to přinejmenším jeden z vrcholů modernistické právní teorie.[39] Původní terminologie, která byla uvedena v prvním vydání, však již byla obsažena v mnoha Kelsenových spisech z 20. let 20. století a byla předmětem diskuse v kritickém tisku tohoto desetiletí. I když je druhé vydání mnohem delší, obě vydání mají hodně podobného obsahu.

Kelsenovy rozsáhlé příspěvky k právní teorii

Kelsenova teorie čerpala z a byla vyvinuta vědci v jeho domovinách, zejména ve Vídeňské škole v Rakousko a brněnská škola pod vedením Františka Weyra v Československo. Uvádí se, že v anglicky mluvícím světě, a zejména na „oxfordské škole“ jurisprudence “, lze Kelsenův vliv vidět v H. L. A. Hart, Julie Dickson, John Gardner, Leslie Green, Jim Harris, Tony Honoré, Joseph Raz a Richard Tur "a" v backhanded kompliment namáhavé kritiky, také v práci John Finnis ".[40] Mezi hlavní autory v angličtině na Kelsenu jsou Robert S. Summers, Neil MacCormick a Stanley L. Paulson. Mezi hlavní kritiky Kelsena dnes patří Joseph Raz z Kolumbijské univerzity, který nadšeně četl Norimberk a soudy o válečných zločinech, které Kelsen interpretoval důsledně po celé 30. a 40. léta na konci své eseje o Dopoledne. J. Juris., 94, (1974) s názvem „Kelsenova teorie základní normy“.

Nějaké tajemství obklopuje opožděnou publikaci z roku 2012 Sekulární náboženství.[41] Text byl zahájen v 50. letech jako útok na práci jeho bývalého žáka Eric Voegelin. Na počátku šedesátých let byla jako důkaz vytvořena rozšířená verze, ale byla stažena na Kelsenovo naléhání (a značné osobní výdaje při proplácení vydavatele), a to z důvodů, které nikdy nebyly jasné. Institut Hansa Kelsena se však nakonec rozhodl, že by měl být zveřejněn. Jedná se o energickou obranu moderní vědy proti všem, včetně Voegelina, který by zvrátil úspěchy osvícenství tím, že požaduje, aby se věda řídila náboženstvím. Kelsen se snaží odhalit rozpory ve svém tvrzení, že moderní věda koneckonců spočívá na stejných předpokladech jako náboženství - že představuje formy „nového náboženství“, a proto by si neměla stěžovat, když je staré náboženství přivedeno zpět.[42] Čtyři hlavní oblasti Kelsenových příspěvků k právní teorii za jeho celého života zahrnovaly následující oblasti (i) soudního přezkumu, (ii) hierarchického práva, (iii) deideologizace pozitivního práva, aby se silně oddělila veškerá zmínka o přirozeném právu, a ( iv) jasné vymezení vědy práva a právní vědy v moderním právu dvacátého století.

Soudní přezkoumání

Soudní přezkum ve věci Kelsen ve dvacátém století byl součástí tradice zděděné od tradice obecného práva založené na amerických ústavních zkušenostech, jak ji zavedl John Marshall.[43] V době, kdy se zásada dostala do Evropy, konkrétně do Kelsenu, se otázka kodifikace Marshallovy verze soudního přezkumu podle obecného práva do podoby ústavně legislativního práva stala pro Kelsena výslovným tématem. Při přípravě ústav pro Rakousko i Československo se Kelsen rozhodl pečlivě vymezit a omezit oblast soudního přezkumu na užší zaměření, než jaké původně pojal John Marshall. Kelsen dostal doživotní jmenování k soudu soudního přezkumu v Rakousku a zůstal na něm téměř po celé desetiletí během 20. let.

Hierarchický zákon

Hierarchické právo jako model pro pochopení strukturálního popisu procesu porozumění a uplatňování práva bylo pro Kelsena ústřední a model převzal přímo od svého kolegy Adolfa Merkla z vídeňské univerzity. Hlavní účely hierarchického popisu zákona by byly pro Kelsena trojí. Nejprve bylo nezbytné porozumět jeho slavné statické teorii práva, jak je rozpracována ve čtvrté kapitole jeho knihy o Čistá teorie práva (viz pododdíl výše).[44] Ve svém druhém vydání měla tato kapitola o statické teorii práva délku téměř sto stran a představovala komplexní studii práva schopnou stát se samostatným předmětem výzkumu pro právníky v této oblasti specializace. Zadruhé šlo o míru relativní centralizace nebo decentralizace. Zatřetí, plně centralizovaný právní systém by také odpovídal jedinečné Grundnorm nebo základní normě, která by nebyla horší než jakákoli jiná norma v hierarchii kvůli jejímu umístění na nejvyšším základě hierarchie (viz část Grundnorm níže).

Odideologizace pozitivního práva

Kelsen během svého vzdělávání a právnické přípravy v Evropě fin-de-siecle zdědil velmi nejednoznačnou definici přirozeného práva, kterou lze prezentovat jako metafyzickou, teologickou, filozofickou, politickou, náboženskou nebo ideologickou v závislosti na kterýkoli z mnoha zdrojů, kteří by chtěli tento výraz použít. Pro Kelsena tato nejasnost v definici přírodního způsobila, že je v praktickém smyslu nepoužitelná pro moderní přístup k porozumění vědě práva. Kelsen výslovně definoval pozitivní právo, aby se vypořádal s mnoha nejasnostmi, které spojoval s používáním přirozeného práva ve své době, spolu s negativním vlivem, který měl na přijetí toho, co bylo míněno i pozitivním právem v kontextech zjevně odstraněných z oblasti vliv obvykle spojený s přirozeným zákonem.

Věda o právu

Předefinování vědy práva a právní vědy tak, aby splňovaly požadavky moderního práva ve dvacátém století, bylo pro Kelsena velmi důležité. Kelsen by psal knihy dlouhé studie popisující mnoho rozdílů, které je třeba udělat mezi přírodními vědami a jejich související metodou kauzálního uvažování na rozdíl od metodologie normativní uvažování, které považoval za vhodnější pro právní vědy.[45] Věda o právu a právní věda byly klíčové metodologické rozdíly, které měly pro Kelsena velký význam při vývoji čisté teorie práva a při obecném projektu odstranění nejednoznačných ideologických prvků z nepatřičného vlivu na vývoj moderního práva dvacátého století. V posledních letech se Kelsen obrátil ke komplexní prezentaci svých myšlenek o normách. Nedokončený rukopis byl vydán posmrtně jako Allgemeine Theorie der Normen (Obecná teorie norem).[46]

Politická filozofie

Během posledních 29 let svého života na Kalifornské univerzitě byl Kelsen jmenován na univerzitě a jeho vztah byl primárně s katedrou politiky a ne se školou práva. To se silně odráží v jeho mnoha spisech v oblasti politické filozofie před i po vstupu na fakultu v Berkeley. Ve skutečnosti byla o Kelsenově první knize (viz část výše) napsána politická filozofie Dante Alighieri a teprve ve své druhé knize začal Kelsen psát knihy o filozofii práva a jeho praktických aplikacích. Baume hovoří o Kelsenově politické filozofii týkající se soudního přezkumu jako o nejblíže Ronaldovi Dworkinovi a Johnu Hartovi Elymu mezi vědci aktivními po skončení Kelsenova života.[47]

Pro získání užitečného pochopení šíře Kelsenových zájmů v politické filozofii je informativní prozkoumat knihu Charlese Covella s názvem Předefinování konzervatismu od 80. let, kdy Covell angažuje Kelsena ve filozofickém kontextu Ludwiga Wittgensteina, Rogera Scrutona, Michaela Oakeshotta, Johna Caseyho a Maurice Cowlinga.[48] Ačkoli Kelsenovy vlastní politické preference byly obecně zaměřeny na liberálnější formy vyjádření, Covellův pohled na moderní liberální konzervatismus ve své knize poskytuje účinnou fólii pro uvedení Kelsenových vlastních bodů důrazu v rámci jeho vlastní orientace v politické filozofii. As Covell summarizes them, Kelsen's interests in political philosophy ranged across the fields of "practical perspectives underlying morality, religion, culture, and social custom."[49]

As summarized by Sandrine Baume in her recent book[50] on Kelsen, "In 1927 [Kelsen] recognized his debt to Kantianism on this methodological point that determined much of his pure theory of law: 'Purity of method, indispensable to legal science, did not seem to me to be guaranteed by any philosopher as sharply as by Kant with his contrast between Is and Ought. Thus for me, Kantian philosophy was from the very outset the light that guided me.'"[51] Kelsen's high praise of Kant in the absence of any specific neo-Kantians is matched among more recent scholars by John Rawls of Harvard University.[52] Both Kelsen and Rawls also have made strong endorsements of Kant's books on Věčný mír (1795) a Idea for a Universal History (1784). Ve své knize s názvem What is Justice?, Kelsen indicated his position concerning social justice stating, "[S]uppose that it is possible to prove that the economic situation of a people can be improved so essentially by so-called planned economy that social security is guaranteed to everybody in an equal measure; but that such an organization is possible only if all individual freedom is abolished. The answer to the question whether planned economy is preferable to free economy depends on our decision between the values of individual freedom and social security. Hence, to the question of whether individual freedom is a higher value than social security or vice versa, only a subjective answer is possible,"[53]

Five principal areas of concern for Kelsen in the area of political philosophy can be identified among his many interests for their centrality and the effect which they exerted over virtually his entire lifetime. Tyto jsou; (i) Sovereignty, (ii) Law-state identity theory, (iii) State-society dualism, (iv) Centralization-decentralization, and (v) Dynamic theory of law.

Suverenita

The definition and redefinition of sovereignty for Kelsen in the context of twentieth century modern law became a central theme for the political philosophy of Hans Kelsen from 1920 to the end of his life.[54] The sovereignty of the state defines the domain of jurisdiction for the laws which govern the state and its associated society. The principles of explicitly defined sovereignty would become of increasing importance to Kelsen as the domain of his concerns extended more comprehensively into international law and its manifold implications following the conclusion of WWI. The very regulation of international law in the presence of asserted sovereign borders would present either a major barrier for Kelsen in the application of principles in international law, or represent areas where the mitigation of sovereignty could greatly facilitate the progress and effectiveness of international law in geopolitics.

Law–state identity theory

The understanding of Kelsen's highly functional reading of the identity of law and state continues to represent one of the most challenging barriers to students and researchers of law approaching Kelsen's writings for the first time. After Kelsen completed his doctoral dissertation on the political philosophy of Dante, he turned to the study of Jellinek's dualist theory of law and state in Heidelberg in the years leading to 1910.[55] Kelsen found that although he had a high respect for Jellinek as a leading scholar of his day, that Jellinek endorsement of a dualist theory of law and state was an impediment to the further development of a legal science which would be supportive of the development of responsible law throughout the twentieth century in addressing the requirements of the new century for the regulation of its society and of its culture. Kelsen's highly functional reading of the state was the most compatible manner he could locate for allowing for the development of positive law in a manner compatible with the demands of twentieth century geopolitics.

State–society distinctions and delineations

After accepting the need for endorsing an explicit reading of the identity of law and state, Kelsen remained equally sensitive to recognizing the need for society to nonetheless express tolerance and even encourage the discussion and debate of philosophy, sociology, theology, metaphysics, sociology, politics, and religion. Culture and society were to be regulated by the state according to legislative and constitutional norms. Kelsen recognized the province of society in an extensive sense which would allow for the discussion of religion, natural law, metaphysics, the arts, etc., for the development of culture in its many and varied attributes. Very significantly, Kelsen would come to the strong inclination in his writings that the discussion of justice, as one example, was appropriate to the domain of society and culture, though its dissemination within the law was highly narrow and dubious.[56] A twentieth century version of modern law, for Kelsen, would need to very carefully and appropriately delineate the responsible discussion of philosophical justice if the science of law was to be allowed to progress in an effective manner responding to the geopolitical and domestic needs of the new century.

Centralization and decentralization

A common theme which was unavoidable for Kelsen within the many applications he encountered of his political philosophy was that of centralization and decentralization. For Kelsen, centralization was a philosophically key position to the understanding of the pure theory of law. The pure theory of law is in many ways dependent upon the logical regress of its hierarchy of superior and inferior norms reaching a centralized point of origination in the hierarchy which he termed the Základní norma nebo Grundnorm. In Kelsen's general assessments, centralization was to often be associated with more modern and highly developed forms of enhancements and improvements to sociological and cultural norms, while the presence of decentralization was a measure of more primitive and less sophisticated observations concerning sociological and cultural norms.

Dynamic theory of law

The dynamic theory of law is singled out in this subsection discussing the political philosophy of Hans Kelsen for the very same reasons which Kelsen applied in separating its explication from the discussion of the static theory of law within the pages of Pure Theory of Law. The dynamic theory of law is the explicit and very acutely defined mechanism of state by which the process of legislation allows for new law to be created, and already established laws to be revised, as a result of political debate in the sociological and cultural domains of activity. Kelsen devotes one of his longest chapters in the revised version of Pure Theory of Law to discussing the central importance he associated with the dynamic theory of law. Its length of nearly one hundred pages is suggestive of its central significance to the book as a whole and may almost be studied as an independent book in its own right complementing the other themes which Kelsen covers in this book.[57]

Recepce a kritika

This section delineates the reception and criticism of Kelsen's writings and research throughout his lifetime. It also explicates the reaction of his scholarly reception after his death in 1973 concerning his intellectual legacy. Throughout his lifetime, Kelsen maintained a highly authoritative position representing his wide range of contributions to the theory and practice of law. Few scholars in the study of law were able to match his ability to engage and often polarize legal opinion during his own lifetime and extending well into his legacy reception after his death. One significant example of this involves his introduction and development of the term Grundnorm which can be briefly summarized to illustrate the diverse responses which his opinion was able to often stimulate in the legal community of his time. The short version of its reception is illustrative of many similar debates with which Kelsen was involved at many points in his career and may be summarized as follows.

The Grundnorm

Regarding Kelsen's original use of the term Grundnorm, its closest antecedent appears in writings of his colleague Adolf Merkl at the University of Vienna. Merkl was developing a structural research approach for the understanding of law as a matter of the hierarchical relationship of norms, largely on the basis of their being either superior, the one to the other, or inferior with respect to each other. Kelsen adapted and assimilated much of Merkl's approach into his own presentation of the Pure Theory of Law in both its original version (1934) and its revised version (1960). For Kelsen, the importance of the Grundnorm was in large measure two-fold since it importantly indicated the logical regress of superior relationships between norms as they led to the norm which ultimately would have no other norm to which it was inferior. Its second feature was that it represented the importance which Kelsen associated with the concept of a fully centralized legal order in contrast to the existence of decentralized forms of government and representing legal orders.

Another form of the reception of the term originated from the fairly extended attempt to read Kelsen as a neo-Kantian following his early engagement with Hermann Cohen 's work in 1911,[58] the year his Habilitace disertační práce dne veřejné právo byl publikován. Cohen was a leading neo-Kantian of the time and Kelsen was, in his own way, receptive to many of the ideas which Cohen had expressed in his published book review of Kelsen's writing. Kelsen had insisted that he had never used this material in the actual writing of his own book, though Cohen's ideas were attractive to him in their own right. This has resulted in one of the longest-running debates within the general Kelsen community as to whether Kelsen became a neo-Kantian himself after the encounter with Cohen's work, or if he managed to keep his own non-neo-Kantian position intact which he claimed was the prevailing circumstance when he first wrote his book in 1911.

The neo-Kantians, when pressing the issue, would lead Kelsen into discussions concerning whether the existence of such a Grundnorm (Basic Norm) was strictly symbolic or whether it had a concrete foundation. This has led to the further division within this debate concerning the currency of the term Grundnorm as to whether it should be read, on the one hand, as part and parcel of Hans Vaihinger 's "as-if" hypothetical construction. On the other hand, to those seeking a practical reading, the Grundnorm corresponded to something directly and concretely comparable to a sovereign nation's federal constitution, under which would be organized all of its regional and local laws, and no law would be recognized as being superior to it.[59]

In different contexts, Kelsen would indicate his preferences in different ways, with some neo-Kantians asserting that late in life Kelsen would largely abide by the symbolic reading of the term when used in the neo-Kantian context,[60] and as he has documented. The neo-Kantian reading of Kelsen can further be subdivided into three subgroups, with each representing their own preferred reading of the meaning of the Grundnorm, which were identifiable as (a) the Marburg neo-Kantians, (b) the Baden neo-Kantians, and (c) his own Kelsenian reading of the neo-Kantian school (during his "analytico-linguistic" phase circa 1911–1915)[61] with which his writings on this subject are often associated.

Reception during Kelsen's European years

This section covers Kelsen's years in Austria,[62] Germany, Czechoslovakia and Switzerland. While still in Austria, Kelsen entered the debate on the versions of Public Law prevailing in his time by engaging the predominating opinions of Jellinek and Gerber in his 1911 Habilitation dissertation (see description above). Kelsen, after attending Jellinek's lectures in Heidelberg oriented his interpretation according to the need to extend Jellinek's research past the points which Jellinek had set as its limits. For Kelsen, the effective operation of a legal order required that it be separated from political influences in terms which exceeded substantially the terms which Jellinek had adopted as its preferred form. In response to his 1911 dissertation, Kelsen was challenged by the neo-Kantians, originally led by Hermann Cohen, who maintained that there were substantial neo-Kantian insights which were open to Kelsen, which Kelsen himself did not appear to develop to the full extent of their potential interpretation as summarized in the section above. Sara Lagi in her recent book on Kelsen and his 1920s writings on democracy has articulated the revised and guarded reception of Jellinek by Kelsen.[63] Kelsen was the principal author of the passages for the incorporation of judicial review in the Constitutions of Austria and Czechoslovakia during the 1910s largely on the model of John Marshall and the American Constitutional experience.

In addition to this debate, Kelsen had initiated a separate discussion with Carl Schmitt on questions relating to the definition of sovereignty and its interpretation in international law. Kelsen became deeply committed to the principle of the adherence of the state to the rule of law above political controversy, while Schmitt adhered to the divergent view of the state deferring to political fiat. The debate would have the effect of polarizing opinion not only throughout the 1920s and 1930s leading up to WWII, but has also extended into the decades after Kelsen's death in 1973.

A third example of the controversies with which Kelsen was involved during his European years surrounded the severe disenchantment which many felt concerning the political and legal outcomes of WWI and the Treaty of Versailles. Kelsen believed that the blamelessness associated with Germany's political leaders and military leaders indicated a gross historical inadequacy of international law which could no longer be ignored. Kelsen devoted much of his writings from the 1930s and leading into the 1940s towards reversing this historical inadequacy which was deeply debated until ultimately Kelsen succeeded in contributing to the international precedent of establishing war crime trials for political leaders and military leaders at the end of WWII at Nuremberg and Tokyo.

Critical reception during his American years

This section covers Kelsen's years during his American years. Kelsen's participation and his part in the establishment of war crimes tribunals following WWII has been discussed in the previous section. The end of WWII and the start of the Spojené národy became a significant concern for Kelsen after 1940. For Kelsen, in principle, the United Nations represented in potential a significant phase change from the previous liga národů and its numerous inadequacies which he had documented in his previous writings. Kelsen would write his 700-page treatise on the United Nations,[64] along with a subsequent two hundred page supplement,[65] which became a standard text book on studying the United Nations for over a decade in the 1950s and 1960s.[66]

Kelsen also became a significant contributor to the Cold War debate in publishing books on Bolshevism and Communism, which he reasoned were less successful forms of government when compared to Democracy. This, for Kelsen, was especially the case when dealing with the question of the compatibility of different forms of government in relation to the Pure Theory of Law (1934, first edition).

The completion of Kelsen's second edition of his magnum opus on Pure Theory of Law published in 1960 had at least as large an effect upon the international legal community as did the first edition published in 1934. Kelsen was a tireless defender of the application legal science in defending his position and was constantly confronting detractors who were unconvinced that the domain of legal science was sufficient to its own subject matter. This debate has continued well into the twenty-first century as well.

Two critics of Kelsen in the United States were the legal realist Karl Llewellyn[67] and the jurist Harold Laski.[68] Llewellyn, as a firm anti-positivist against Kelsen stated, "I see Kelsen's work as utterly sterile, save in by-products that derive from his taking his shrewd eyes, for a moment, off what he thinks of as 'pure law.'"[69] In his democracy essay of 1955, Kelsen took up the defense of representative democracy made by Joseph Schumpeter in Schumpeter's book on democracy and capitalism.[70] Although Schumpeter took a position unexpectedly favorable to socialism, Kelsen felt that a rehabilitation of the reading of Schumpeter's book more amicable to democracy could be defended and he quoted Schumpter's strong conviction that, to "realize the relative validity of one's convictions and yet stand for them unflinchingly," as consistent with his own defense of democracy.[71] Kelsen himself made mixed statements concerning the extensiveness of the greater or lesser strict association of democracy and capitalism.[72]

Critical reception of Kelsen's legacy after 1973

Many of the controversies and critical debates during his lifetime continued after Kelsen's death in 1973. Kelsen's ability to polarize opinion among established legal scholars continued to influence the reception of his writings well after his death. The formation of the European Union would recall many of his debates with Schmitt on the issue of the degree of centralization which would in principle be possible, and what the implications concerning state sovereignty would be once the unification was put into place. Kelsen's contrast with Hart as representing two distinguishable forms of legal positivism has continued to be influential in distinguishing between Anglo-American forms of legal positivism from Continental forms of legal positivism. The implications of these contrasting forms continues to be part of the continuing debates within legal studies and the application of legal research at both the domestic and the international level of investigation.[73]

In her recent book on Hans Kelsen, Sandrine Baume[74] identified Ronald Dworkin as a leading defender of the "compatibility of judicial review with the very principles of democracy." Baume identified John Hart Ely alongside Dworkin as the foremost defenders of this principle in recent years, while the opposition to this principle of "compatibility" was identified as Bruce Ackerman and Jeremy Waldron.[75] Dworkin has been a long-time advocate of the principle of the moral reading of the Constitution whose lines of support he sees as strongly associated with enhanced versions of judicial review in the federal government. In Sandrine Baume's words, the opposing view to compatibility is that of "Jeremy Waldron and Bruce Ackerman,[76] who look on judicial review as inconsistent with respecting democratic principles."[77]

Hans Kelsen Institute and Hans Kelsen Research Center

For the occasion of Hans Kelsen's 90th birthday, the Austrian federal government decided on 14 September 1971 to establish a foundation bearing the name "Hans Kelsen-Institut". The Institut became operational in 1972. Its task is to document the Pure Theory of Law and its dissemination in Austria and abroad, and to inform about and encourage the continuation and development of the pure theory. To this end it produces, through the publishing house Manz, a book series that currently runs to more than 30 volumes. The Institut administers the rights to Kelsen's works and has edited several works from his unpublished papers, including General Theory of Norms (1979, translated 1991)[78] a Sekulární náboženství (2012, written in English).[79] The Institut's database is free online with login registration.[80] The founding directors of the Institut, Kurt Ringhofer and Robert Walter, held their posts until their deaths respectively in 1993 and 2010. The current directors are Clemens Jabloner (since 1993)[81][82] and Thomas Olechowski (since 2011).[83]

In 2006, the Hans-Kelsen-Forschungsstelle (Hans Kelsen Research Center) was founded under the direction of Matthias Jestaedt at the Friedrich-Alexander University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. After Jestaedt's appointment at the Albert-Ludwigs-University of Freiburg in 2011, the center was transferred there. The Hans-Kelsen-Forschungsstelle publishes, in cooperation with the Hans Kelsen-Institut and through the publishing house Mohr Siebeck, a historical-critical edition of Kelsen's works which is planned to reach more than 30 volumes; as of July 2013, the first five volumes have been published.

An extensive biography of Kelsen by Thomas Olechowski, Hans Kelsen: Biographie eines Rechtswissenschaftlers (Hans Kelsen: Biography of a Legal Scientist), was published in May 2020.[84]

Vyznamenání a ocenění

- 1938: Honorary Member of the Americká společnost mezinárodního práva

- 1953: Karl Renner Prize

- 1960: Feltrinelliho cena

- 1961: Grand Merit Cross with Star of the Federal Republic of Germany

- 1961: Rakouská dekorace pro vědu a umění

- 1966: Ring of Honour of the City of Vienna

- 1967: Great Silver Medal with Star for Services to the Republic of Austria

- 1981: Kelsenstrasse in Vienna Landstrasse (3rd District) named after him

Bibliografie

- Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts (1920).

- Reine Rechtslehre, Vienna 1934. Introduction to the Problems of Legal Theory (1934; Litschewski Paulson and Paulson trans.), Oxford 1992; the translators have adopted the subtitle, Einleitung in die rechtswissenschaftliche Problematik, in order to avoid confusion with the English translation of the second edition.

- Law and Peace in International Relations, Cambridge (Mass.) 1942, Union (N.J.) 1997.

- Society and Nature. 1943, The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. 2009 ISBN 1584779861

- Peace Through Law, Chapel Hill 1944, Union (N.J.) 2000.

- The Political Theory of Bolshevism: A Critical Analysis, University of California Press 1948, The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd. 2011.

- The Law of the United Nations. First published under the auspices of The London Institute of World Affairs in 1950. With a supplement, Recent Trends in the Law of the United Nations [1951]. A critical, detailed, highly technical legal analysis of the United Nations charter and organization. Originally published conjointly: New York: Frederick A. Praeger, [1964].

- Reine Rechtslehre, 2nd edn Vienna 1960 (much expanded from 1934 and effectively a different book); Studienausgabe with amendments, Vienna 2017 ISBN 978-3-16-152973-3

- Pure Theory of Law (1960; Knight trans.), Berkeley 1967, Union (N.J.) 2002.

- Théorie pure du droit (1960; Eisenmann French trans.), Paris 1962.

- General Theory of Law and State (German original unpublished; Wedberg trans.), 1945, New York 1961, Clark (N.J.) 2007.

- What is Justice?, Berkeley 1957.

- 'The Function of a Constitution' (1964; Stewart trans.) in Richard Tur and William Twining (eds), Essays on Kelsen, Oxford 1986; also in 5th and later editions of Lloyd's Introduction to Jurisprudence, London (currently 8th ed 2008).

- Essays in Legal and Moral Philosophy (Weinberger sel., Heath trans.), Dordrecht 1973.

- Allgemeine Theorie der Normen (ed. Ringhofer and Walter), Vienna 1979; see English translation in 1990 below.

- Die Rolle des Neukantianismus in der Reinen Rechtslehre: eine Debatte zwischen Sander und Kelsen (German Edition) by Hans Kelsen and Fritz Sander (Dec 31, 1988).

- General Theory of Norms (1979; Hartney trans.), Oxford 1990.

- Secular Religion: a Polemic against the Misinterpretation of Modern Social Philosophy, Science, and Politics as "New Religions" (ed. Walter, Jabloner and Zeleny), Vienna and New York 2012 (written in English), revised edition 2017.

Viz také

Reference

- ^ Christian Damböck (ed.), Vlivy na Aufbau, Springer, 2015, s. 258.

- ^ "Kelsen, der Kampf um die "Sever-Ehen"".

- ^ Métall, Rudolf Aladár (1969), Hans Kelsen: Leben und Werke, Vienna: Deuticke, pp. 1–17; but preferring Kelsen's autobiographical fragments (1927 and 1947), as well as the editorial additions, in Hans Kelsen, Werke Bd 1 (2007).

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1905), Die Staatslehre des Dante Alighieri, Vienna: Deuticke. Neither this thesis nor his habilitation thesis appears to have had a formal supervisor—"Autobiographie". Hans Kelsen Werke. 1: 29–91.:36–8

- ^ Lepsius, Oliver (2017). "Hans Kelsen on Dante Alighieri's Political Philosophy". Evropský žurnál mezinárodního práva. 27 (4): 1153. doi:10.1093/ejil/chw060.

- ^ A b Kelsen, Dante, concluding chapter.

- ^ A b Baume (2011), str. 47

- ^ Kelsen, Hans. Obecná teorie práva a státu, str. 198.

- ^ Duguit, Leon (1911). Traité de droit constitutionnel, sv. 1, La règle du droit: le problème de l'État, Paris: de Boccard, p. 645.

- ^ Kelsen, p. 198.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1911), Hauptprobleme der Staatsrechtslehre entwickelt aus der Lehre vom Rechtssatze (1923 2nd ed.), Tübingen: Mohr; reprinted, Aalen, Scientia, 1984, ISBN 3-511-00055-6 (an index was issued separately by the Hans Kelsen-Institut in 1988). Also published as Kelsen, Werke, sv. II.

- ^ Baume (2011), str. 7

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1920), Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts, Tübingen: Mohr. Má titulky Beitrag zu einer reinen Rechtslehre (Essay toward a Pure Theory of Law).

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1920), Vom Wesen und Wert der Demokratie, Tübingen: Mohr. Second, revised and enlarged edition 1929; reprinted, Aalen, Scientia, 1981, ISBN 3-511-00058-0.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1920), Der soziologische und der juristische Staatsbegriff, Tübingen: Mohr; reprinted, Aalen, Scientia, 1981, ISBN 3-511-00057-2.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1923), Österreichisches Staatsrecht, Tübingen: Mohr

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1925), Allgemeine Staatslehre, Berlín: Springer.

- ^ These works remain untranslated, except that key parts of Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts appear in Petra Gümplová, Sovereignty and Constitutional Democracy (Nomos Publishers, 2011).

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1928), Die philosophischen Grundlagen der Naturrechtslehre und des Rechtspositivismus, Charlottenburg: Pan-Verlag Rolf Heise; translated as "Natural Law Doctrine and Legal Positivism" in Kelsen, Hans (1945), Obecná teorie práva a státu, Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard U.P., pp. 389–446.

- ^ Baume (2011)

- ^ "Constitutional court of the Czechoslovak republic and its fortunes in years 1920-1948 - Ústavní soud".

- ^ A b Baume (2011), str. 37

- ^ Le Divellec, 'Les premices de la justice...,' p. 130.

- ^ J.-C. Beguin, Le contrôle de la constitutionnalité des lois en République fédérale d'Allemagne, Paris: Economica, 1982, p. 20.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans, La réalité des normes en particulier des normes du droit international: fondements d'une théorie des normes, (Paris: Alcan, 1934), still untranslated into English.

- ^ Morgenthau, Hans (2011). Koncept politického, pp 16-17.

- ^ Métall, p. 64.

- ^ Frei (2001), pp. 48-49.

- ^ Morgenthau, p. 17.

- ^ Translated by B.L. Paulson and S.L. Paulson as Introduction to the Problems of Legal Theory (Oxford, Clarendon P., 1992); the German subtitle is used as the English title, to distinguish this book from the second edition of Reine Rechtslehre, translated by Max Knight as Pure Theory of Law (Berkeley, U. California P., 1967).

- ^ Fuller, Lon. "The place and uses of jurisprudence in the law school curriculum,' Journal of Legal Education, 1948-1949, 1, p. 496.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1944), Peace through Law, Chapel Hill: U. North Carolina P., pp. 88–110.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1948). J.Y.B.I.L., "Collective and Individual Responsibility for Acts of State in International Law."

- ^ Dinstein, Yoram (2012). The Defense of 'Obedience to Superior Orders' in International Law, reprinted in 2012. Originally published in Hebrew in 1965 by Manges Press.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1955), "Foundations of Democracy", Etika, 66(1/2) (1): 1–101, doi:10.1086/291036, JSTOR 2378551

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1957), What is Justice? Justice, Law, and Politics in the Mirror of Science, Berkeley: U. California P..

- ^ Crapanzano, Vincent (2000). Serving the Word: Literalism in America from the Pulpit to the Bench. New York: The New Press. str.271–275. ISBN 1-56584-673-7.

- ^ The title page gives the title correctly as Pure Theory of Law, but the paperback cover has The Pure Theory of Law.

- ^ Both editions will be included in forthcoming volumes in the Hans Kelsen Werke Archivováno 2013-10-29 na Wayback Machine. A fuller and more accurate translation of the second edition is also planned. The current translation, in omitting many footnotes, obscures the extent to which the Pure Theory of Law is both philosophically grounded and responsive to earlier theories of law.

- ^ Luis Duarte d'Almeida, John Gardner and Leslie Green, ed. (2013). "Úvod". Kelsen Revisited: New Essays on the Pure Theory of Law. Hart Publishing. str. 1.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (2012). Secular Religion: a Polemic against the Misinterpretation of Modern Social Philosophy, Science, and Politics as "New Religions". Vienna and New York: Springer. ISBN 978-3-7091-0765-2. Edited by members of the Hans Kelsen Institute

- ^ Stewart, Iain (2012), "Kelsen, the Enlightenment and Modern Premodernists", Australian Journal of Legal Philosophy, 37: 251–278

- ^ Wolfe, Christopher. The Rise of Modern Judicial Review: From Judicial Interpretation to Judge-Made LawRowman a Littlefield.

- ^ Kelsen (1960), Kapitola 4

- ^ Kelsen, Hans. Společnost a příroda. The Lawbook Exchange, Ltd.; Reprint edition (November 2, 2009), 399 pages, ISBN 1584779861

- ^ Kelsen, Hans. General Theory of Norms, Oxford University Press.

- ^ Baume (2011), s. 2–9

- ^ Covell, Charles (1985). The Redefinition of Conservatism: Politics and Doctrine. N.Y.: St. Martin's Press.

- ^ Covell, Charles (1985). The Redefinition of Conservatism: Politics and Doctrine. N.Y.: St. Martin's Press, p. 4

- ^ Baume (2011), str. 5

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1927). Selbstdarstellung in Jestaedt (ed.), Hans Kelsen im Selbstzeugnis, pp. 21-29, especially p. 23.

- ^ Rawls, John (2000). Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy. Cambridge, Massachusetts, Harvard University Press, 2000. This collection of lectures was edited by Barbara Herman. It has an introduction on modern moral philosophy from 1600–1800 and then lectures on Hume, Leibniz, Kant, and Hegel.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans. What is Justice?, pp 5-6.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1920). Das problem der souveränität und die theorie des völkerrechts (Jan 1, 1920).

- ^ Hans Kelsen Werke 2Bd Hardcover – December 1, 2008, Matthias Jestaedt (Editor). Volume 2 of the Kelsen Werke published his book on Administrative Law following immediately his encounter with Jellinek and his debate with Jellinek's dualism.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans. What is Justice?

- ^ Kelsen (1960), Kapitola 5

- ^ Mónica García-Salmones Rovira, Projekt pozitivismu v mezinárodním právu, Oxford University Press, 2013, s. 258 n. 63.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans. Das Problem der Souveränität und die Theorie des Völkerrechts. Beitrag zu einer reinen Rechtslehre (The Problem of Sovereignty and Theory of International Law: Contribution to a Pure Theory of Law). Tübingen, Mohr, 1920.

- ^ Die Rolle des Neukantianismus in der Reinen Rechtslehre: eine Debatte zwischen Sander und Kelsen by Hans Kelsen, Fritz Sander (1988).

- ^ Stanley L. Paulson, "Four Phases in Hans Kelsen's Legal Theory? Reflections on a Periodization", Oxford Journal of Legal Studies, 18(1) (Spring, 1998), pp. 153–166, esp. 154.

- ^ Die Wiener rechtstheoretische Schule. Schriften von Hans Kelsen, Adolf Merkl, Alfred Verdross.

- ^ Lagi, Sara (2007). The Political Thought of Hans Kelsen (1911-1920). Original in Italian, with Spanish translation separately published.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans. The Law of the United Nations. First published under the auspices of The London Institute of World Affairs in 1950.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans. Supplement, Recent Trends in the Law of the United Nations [1951].

- ^ Kelsen, Hans. A critical, detailed, highly technical legal analysis of the United Nations charter and organization. Original conjoint publication: New York: Frederick A. Praeger, [1964].

- ^ Llewellyn, Karl (1962). Jurisprudence. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, str. 356, n. 6.

- ^ Laski, Harold (1938). A Grammar of Politics. London: Allen and Unwin, p. vi.

- ^ Llewellyn, p. 356

- ^ Schumpeter, Joseph (1942). Kapitalismus, socialismus a demokracie.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1955). Foundations of Democracy.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1937). "The function of the pure theory of law." In A. Reppy (ed.) Law: A Century of Progress 1835-1935, 3 vols., NY: New York University Press and London: OUP, 1937, p.94.

- ^ Essays in Honor of Hans Kelsen, Celebrating the 90th Anniversary of His Birth by Albert A.; Et al. Ehrenzweig (1971).

- ^ Baume (2011), str. 53–54

- ^ Waldron, Jeremy (2006). "The Core of the case against judicial review," The Yale Law Review2006, sv. 115, pp 1346-1406.

- ^ Ackerman, Bruce (1991). My lidé, Cambridge (MA) and London: Harvard University Press, 1991.

- ^ Baume (2011), str. 54

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (1979). General Theory of Norms.

- ^ Kelsen, Hans (2012, 2017). Sekulární náboženství.

- ^ Hans Kelsen-Institut Datenbank (v němčině). Vyvolány 18 March 2015.

- ^ Jabloner, Clemens, "Hans Kelsen and his Circle: the Viennese Years" (1998) 9 Evropský žurnál mezinárodního práva 368.

- ^ Jabloner, Clemens (2009). Logischer Empirismus und Reine Rechtslehre: Beziehungen zwischen dem Wiener Kreis und der Hans Kelsen-Schule, (Veröffentlichungen des Instituts Wiener Kreis) (German Edition) Paperback by Clemens Jabloner (Editor), Friedrich Stadler (Editor).

- ^ Olechowski, Thomas; Robert Walter; Werner Ogris (2009). Hans Kelsen: Leben, Werke, Manz'Sche Verlags- U. Universitatsbuchhandlung (November 1, 2009), ISBN 3214147536, https://www.amazon.de/Hans-Kelsen-Leben-Werk-Wirksamkeit/dp/3214147536/ref=sr_1_5?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1383848130&sr=1-5&keywords=kelsen+thomas

- ^ Olechowski, Thomas (2020). Hans Kelsen: Biographie einer Rechtswissenschaftler. Tübingen: Mohr Siebeck. doi:10.1628/978-3-16-159293-5. ISBN 978-3-16-159293-5.

Zdroje

- Baume, Sandrine (2011). Hans Kelsen and the Case for Democracy. Colchester: ECPR. ISBN 9781907301247.

- Kelsen, Hans (1967) [1960]. Pure Theory of Law. Přeložil Knight, Max. Berkeley, CA: U. California P.

Další čtení

- Uta Bindreiter, Why Grundnorm? A Treatise on the Implications of Kelsen's Doctrine, The Hague 2002.

- Essays in Honor of Hans Kelsen, Celebrating the 90th Anniversary of His Birth by Albert A.; Et al. Ehrenzweig (1971).

- Die Wiener rechtstheoretische Schule. Schriften von Hans Kelsen, Adolf Merkl, Alfred Verdross.

- Law and politics in the world community: Essays in Hans Kelsen's pure theory and related problems in international law, by George Arthur Lipsky (1953).

- William Ebenstein, The Pure Theory of Law, 1945; New York 1969.

- Keekok Lee. The Legal-Rational State: A Comparison of Hobbes, Bentham and Kelsen (Avebury Series in Philosophy) (Sep 1990).

- Ronald Moore, Legal Norms and Legal Science: a Critical Study of Hans Kelsen's Pure Theory of Law, Honolulu 1978.

- Stanley L. Paulson and Bonnie Litschewski Paulson (eds), Normativity and Norms: Critical Perspectives on Kelsenian Themes, Oxford 1998.

- Iain Stewart, 'The Critical Legal Science of Hans Kelsen' (1990) 17 Journal of Law and Society 273-308.

- Jochen von Bernstorff, The Public International Law Theory of Hans Kelsen: Believing in Universal Law, Cambridge University Press, 2010; translated from the original German edition, 2001.

externí odkazy

- Works by or about Hans Kelsen na Internetový archiv

- Hans Kelsen-Institut, Vienna

- Hans-Kelsen-Forschungsstelle, Freiburg

- Úplná biografie

- Biographical note 1

- Biographical note 2

- Bibliographical note 1

- Bibliographical note 2 - Kelsen's Werke

- Newspaper clippings about Hans Kelsen v Archivy tisku 20. století z ZBW