George Washington a otroctví - George Washington and slavery

Historie George Washington a otroctví odráží Washington mění postoj k zotročení. Preeminent Zakládající otec Spojených států a otrokář, Washington byl čím dál znepokojenější ta dlouholetá instituce v průběhu svého života a zajišťoval emancipaci svých otroků po jeho smrti.

Otroctví v koloniální Americe byl zakořeněný v ekonomické a sociální struktuře několika kolonií včetně svého rodáka Virginie. V 11 letech, po smrti svého otce v roce 1743, zdědil Washington svých prvních deset otroků. V dospělosti jeho osobní otroctví rostlo dědictvím, nákupem a ... přirozený přírůstek dětí narozených do otroctví. V roce 1759 získal kontrolu nad dower otroci patřící k panství Custisovi při jeho sňatku s Martha Dandridge Custis. Počáteční postoje Washingtonu k otroctví odrážely převládající Virginii květináč názory dne a zpočátku neprokázal žádné morální výčitky ohledně instituce. Začal být skeptický ohledně ekonomické účinnosti otroctví před Americká revoluční válka když jeho přechod z tabák na obilniny v šedesátých letech 20. století ho zanechal nákladný přebytek zotročených dělníků. V roce 1774 Washington veřejně odsoudil obchod s otroky z morálních důvodů v USA Fairfax řeší. Po válce vyjádřil podporu zrušení otroctví postupným legislativním procesem sdílel názor, který sdílel široce, ale vždy v soukromí, a zůstával závislý na otrocké práci. V době jeho smrti v roce 1799 bylo u něj 317 zotročených lidí Mount Vernon statek, 124 vlastněný Washingtonem a zbytek spravovaný jako jeho vlastní majetek, ale patřící jiným lidem.

Washington měl silné pracovní morálka a požadoval totéž od najatých dělníků i od zotročených lidí, kteří byli nuceni pracovat na jeho příkaz. Poskytoval svému zotročenému obyvatelstvu základní stravu, oblečení a ubytování srovnatelné s v té době běžnou praxí, které nebylo vždy adekvátní, a lékařskou péči. Na oplátku očekával, že budou pilně pracovat od východu do západu slunce během šestidenního pracovního týdne, který byl v té době standardní. Asi tři čtvrtiny jeho zotročených dělníků pracovalo na polích, zatímco zbytek pracoval v hlavním sídle jako domácí sluhové a řemeslníci. Doplňovali stravu lovem, odchytem a pěstováním zeleniny ve volném čase a za příjmy z prodeje zvěřiny a produktů si kupovali další dávky, oblečení a domácí potřeby. Vybudovali si vlastní komunitu kolem manželství a rodiny, ačkoli proto, že Washington přidělil zotročené farmy podle požadavků podnikání obecně bez ohledu na jejich vztahy, mnoho manželů žilo během pracovního týdne odděleně od svých manželek a dětí. Washington používal jak odměnu, tak trest k řízení své zotročené populace, ale byl neustále zklamán, když nesplnili jeho náročné standardy. Značná část zotročeného obyvatelstva na hoře Vernon odolávala systému různými způsoby, včetně krádeží za účelem doplnění stravy a oblečení, stejně jako příjmu, předstíráním nemoci a útěkem.

Jako vrchní velitel Kontinentální armáda v roce 1775 zpočátku odmítal přijímat do řad afroameričany, svobodné nebo zotročené, ale poklonil se válečným požadavkům a poté vedl rasově integrovanou armádu. Morální pochybnosti o instituci se poprvé objevily v roce 1778, kdy Washington vyjádřil neochotu prodat některé ze svých zotročených pracovníků na veřejném místě nebo rozdělit jejich rodiny. Na konci války Washington bez úspěchu požadoval, aby Britové respektovali předběžné mírová smlouva což podle něj vyžadovalo návrat uprchlých otroků bez výjimky. Jeho veřejné prohlášení o rezignaci jeho komise, řešení výzev, kterým čelí nové konfederace, výslovně nezmínil otroctví. Politicky měl Washington pocit, že rozporuplná otázka Americké otroctví ohrožoval národní soudržnost a nikdy o tom veřejně nemluvil. Soukromě zvažoval Washington v polovině 90. let 20. století plány na osvobození svého zotročeného obyvatelstva. Tyto plány selhaly kvůli jeho neschopnosti získat potřebné finance, odmítnutí jeho rodiny schválit emancipaci vězněných otroků a vlastní averzi k odloučení zotročených rodin. Jeho vůle byla široce publikována po jeho smrti v roce 1799 a stanovila emancipaci zotročeného obyvatelstva, které vlastnil, jediného otce-zakladatele, který tak učinil. Protože mnoho z jeho zotročených lidí se oženilo s věřícími otroky, které nemohl legálně osvobodit, vůle stanovila, že kromě jeho komorníka Williama Leeho, který byl okamžitě osvobozen, budou jeho zotročení pracovníci emancipováni po smrti jeho manželky Marty. Osvobodila je v roce 1801, rok před vlastní smrtí, ale neměla jinou možnost osvobodit vězněné otroky, které zdědily její vnoučata.

Pozadí

Otroctví bylo zavedeno do angličtiny kolonie Virginie když byli transportováni první Afričané Pohodlí v roce 1619. Ti, kteří přijali křesťanství, se stali „křesťanskými služebníky“ s časově omezeným otroctvím nebo dokonce osvobozeni, ale tento mechanismus pro ukončení otroctví byl postupně zavřen. V roce 1667 Virginské shromáždění přijal zákon, který zakazoval křest jako prostředek přiznávání svobody. Afričanům, kteří byli pokřtěni před příjezdem do Virginie, mohl být udělen status indenturovaný sluha až do roku 1682, kdy je jiný zákon prohlásil za otroky. Bílí lidé a lidé afrického původu v nejnižší vrstvě panenské společnosti sdíleli společné nevýhody a společný životní styl, který zahrnoval sňatky, dokud shromáždění v roce 1691 nestanovilo, že by tyto odbory byly trestány vyhoštěním.[1]

V roce 1671 počítala Virginie mezi svými 40 000 obyvateli 6 000 bílých služebníků, ale pouze 2 000 lidí afrického původu, z nichž až třetina byla v některých krajích svobodná. Ke konci 17. století se anglická politika posunula ve prospěch udržení levné pracovní síly, místo aby ji dodávala do kolonií, a zásoba indenturovaných zaměstnanců ve Virginii začala vysychat; do roku 1715 se roční imigrace pohybovala ve stovkách, ve srovnání s 1 500–2 000 v 80. letech 16. století. Když pěstitelé tabáku obdělávali více půdy, vyrovnali nedostatek pracovních sil se zvyšujícím se počtem zotročených pracovníků. Instituce měla kořeny v závodech s Virginské otrokářské kódy z roku 1705 a přibližně od roku 1710 byl růst zotročené populace poháněn přirozeným přírůstkem. V letech 1700 až 1750 se počet zotročených lidí v kolonii zvýšil z 13 000 na 105 000, téměř osmdesát procent z nich se narodilo ve Virginii.[2] Za života Washingtonu bylo otroctví hluboce zakořeněno v ekonomické a sociální struktuře Virginie, kde bylo zotročeno přibližně čtyřicet procent populace a prakticky všichni afroameričané.[3]

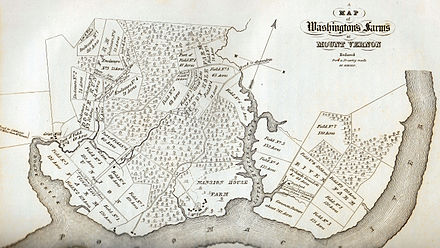

George Washington se narodil v roce 1732 jako první dítě svého otce Augustine druhé manželství. Augustine byl pěstitelem tabáku a měl asi 10 000 akrů půdy (4 000 ha) a 50 otroků. Na jeho smrti v roce 1743, on opustil jeho 2500-akr (1 000 ha) Malý Hunting Creek George staršího nevlastního bratra Lawrence, který jej přejmenoval Mount Vernon. Washington zdědil 260 ha (110 ha) Ferry Farm a deset otroků.[4] Dva roky po smrti svého bratra v roce 1752 si pronajal Mount Vernon od Lawrencovy vdovy a zdědil ji v roce 1761.[5] Byl agresivním spekulantem s půdou a do roku 1774 nashromáždil asi 32 000 akrů půdy v Ohio Země na západní hranici Virginie. Na jeho smrti vlastnil přes 80 000 akrů (32 000 ha).[6][7][8] V roce 1757 zahájil program expanze na Mount Vernon, který by nakonec vyústil v panství o rozloze 3200 ha s pěti samostatnými farmami, na nichž původně pěstoval tabák.[9][A]

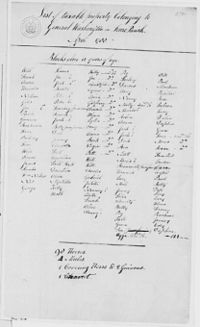

Zemědělská půda vyžadovala pracovní sílu, aby byla produktivní, a na americkém jihu 18. století to znamenalo otrockou práci. Washington zdědil otroky po Lawrenceovi, získal více jako součást podmínek pronájmu Mount Vernon a zdědil otroky znovu po smrti Lawrencovy vdovy v roce 1761.[12][13] Při jeho manželství v roce 1759 až Martha Dandridge Custis, Washington získal kontrolu nad osmdesáti čtyřmi dower otroci. Patřili k panství Custis a Martha jim držela důvěru pro dědice Custis, a přestože na ně Washington neměl právní nárok, spravoval je jako svůj vlastní majetek.[14][15][16] V letech 1752 až 1773 koupil nejméně sedmdesát jedna otroků - mužů, žen a dětí.[17][18] Výrazně omezil svůj nákup zotročených pracovníků po americká revoluce ale nadále je získával, většinou přirozeným přírůstkem a příležitostně vyrovnáním dluhů.[19][17] V roce 1786 uvedl 216 zotročených lidí - 122 mužů a žen a 88 dětí.[b] - což z něj dělá jednoho z největších otrokářů v Fairfax County. Z toho celkem 103 patřilo Washingtonu, zbytek byli otroci věží. V době smrti Washingtonu v roce 1799 se počet obyvatel zotročených na Mount Vernon zvýšil na 317 lidí, včetně 143 dětí. Z toho celkem vlastnil 124, pronajal 40 a ovládal 153 otroků.[21][22]

Otroctví na hoře Vernon

Washington považoval své pracovníky za součást širší rodiny, v jejím čele stál otec. Ve svých postojích k otrokům, které ovládal, zobrazoval prvky patriarchátu i paternalismu. Patriarcha v něm očekával absolutní poslušnost a projevil se přísnou a přísnou kontrolou nad zotročenými dělníky a emocionálním odstupem, který od nich udržoval.[23][24] Existují příklady opravdové náklonnosti mezi pánem a zotročeným, jako tomu bylo v případě jeho komorníka William Lee, ale takové případy byly výjimkou.[25][26] Paternalista v něm viděl jeho vztah se svými zotročenými lidmi jako jeden ze vzájemných závazků; postaral se o ně a oni mu na oplátku sloužili, vztah, ve kterém zotročení byli schopni obracet se na Washington se svými obavami a stížnostmi.[23][27] Otcovští mistři se považovali za velkorysé a zaslouží si vděčnost.[28] Když služka Marthy Jeden soudce uprchl v roce 1796, Washington si stěžoval na „nevděčnost dívky, která byla vychována a zacházeno s ní spíše jako s dítětem než se sluhou“.[29]

Thomas Jefferson, 1799[30][31]

Ačkoli Washington zaměstnával vedoucího farmy, který řídil panství, a dozorce na každé z farem, byl praktickým manažerem, který podnikal s vojenskou disciplínou a zapojoval se do detailů každodenní práce.[34][35] Během delší nepřítomnosti v úředních záležitostech udržoval důkladnou kontrolu prostřednictvím týdenních zpráv od vedoucího farmy a dozorců.[36] Vyžadoval od všech svých pracovníků stejné pečlivé oko pro detail, jaké sám cvičil; bývalý zotročený dělník si později vzpomněl, že „otroci ... neměli docela rádi“ Washington, hlavně proto, že „byl tak přesný a tak přísný ... pokud bylo povoleno zůstat mimo železnici, šindel nebo kámen místo, stěžoval si; někdy v jazyce přísnosti. “[37][38] Podle názoru Washingtonu „ztracenou práci nelze nikdy získat zpět“ a požadoval, aby „každý dělník (muž nebo žena) [udělal] za 24 hodin tolik, kolik jeho síla bez ohrožení zdraví nebo ústavy dovolí“. Měl silnou pracovní morálku a to samé očekával od svých zaměstnanců, zotročených i najatých.[39] Neustále byl zklamán zotročenými dělníky, kteří nesdíleli jeho motivaci a vzdorovali jeho požadavkům, což ho vedlo k tomu, že je považoval za lhostejné, a trval na tom, aby na ně jejich dozorci vždy pečlivě dohlíželi.[40][41][42]

V roce 1799 pracovaly na polích téměř tři čtvrtiny zotročené populace, více než polovina z nich. Byli zaneprázdněni po celý rok, jejich úkoly se lišily podle sezóny.[43] Zbytek pracoval jako domácí sluha v hlavní rezidenci nebo jako řemeslníci, jako tesaři, truhláři, bednáři, přadleny a švadleny.[44] V letech 1766 až 1799 pracovalo v té či oné době sedm dozorčích otroků jako dozorci.[45] Očekávalo se, že zotročení budou pracovat od východu do západu slunce během šestidenního pracovního týdne, což bylo na plantážích ve Virginii standardem. S dvěma hodinami volna na jídlo by se jejich pracovní dny pohybovaly mezi sedmi a půl hodinami až třinácti hodinami, v závislosti na ročním období. Dostali tři nebo čtyři dny volna na Vánoce a každý den na Velikonoce a Svatodušní neděle.[46] Domácí otroci začínali brzy, pracovali do večerů a nutně nemuseli mít neděle a svátky volné.[47] Při zvláštních příležitostech, kdy se od zotročených pracovníků vyžadovalo vynaložení mimořádného úsilí, například při práci na dovolené nebo při sklizni, jim bylo vyplaceno nebo kompenzováno volno.[48]

Washington nařídil svým dozorcům, aby zacházeli s zotročenými lidmi „s lidskostí a něhou“, když byli nemocní.[40] Otroci, kteří byli méně schopní kvůli úrazu, postižení nebo věku, dostali lehké povinnosti, zatímco ti, kteří byli příliš nemocní, aby pracovali, byli obecně, i když ne vždy, omluvenou prací, když se vzpamatovali.[49] Washington jim poskytoval dobrou, někdy nákladnou lékařskou péči - když otrocká osoba jménem Cupid onemocněla zánět pohrudnice Washington ho nechal odvézt do hlavní budovy, kde se o něj mohl lépe starat, a osobně ho po celý den kontroloval.[41][50] Otcovský zájem o blaho jeho zotročených dělníků se mísil s ekonomickým zvážením ztráty produktivity vyplývající z nemoci a smrti pracovní síly.[51][52]

Životní podmínky

Na Mansion House Farm byla většina zotročených lidí umístěna ve dvoupodlažním domě rámová budova známé jako „Quarters for Families“. To bylo v roce 1792 nahrazeno cihlovými ubytovacími křídly po obou stranách skleníku, které obsahovaly celkem čtyři pokoje, každý o rozloze 56 m2). The Dámská asociace Mount Vernon dospěli k závěru, že tyto pokoje byly společnými prostory vybavenými palandami, které umožňovaly malé soukromí převážně mužských obyvatel. Další zotročení lidé na Mansion House Farm žili nad hospodářskými budovami, kde pracovali, nebo ve srubech.[53] Takové sruby byly standardním ubytováním otroků na odlehlých farmách, srovnatelné s ubytováním obsazeným nižšími vrstvami svobodné bílé společnosti v celém Chesapeake oblast a zotročen na dalších Virginijských plantážích.[54] Poskytli jedinou místnost o velikosti od 15,6 m2) na 246 čtverečních stop (22,9 m.)2) k ubytování rodiny.[55] Kabiny byly často špatně postavené, obnažené blátem pro izolaci proti průvanu a vodě, s nečistými podlahami. Některé kabiny byly postaveny jako duplexy; některé kabiny s jednou jednotkou byly dost malé na to, aby se s nimi dalo jezdit na vozících.[56] Existuje několik zdrojů, které osvětlují životní podmínky v těchto chatkách, ale jeden návštěvník v roce 1798 napsal: „Manželé spí na střední paletě, děti na zemi; velmi špatný krb, nějaké nádobí k vaření, ale v uprostřed této chudoby nějaké šálky a čajová konvice “. Jiné zdroje naznačují, že interiéry byly zakouřené, špinavé a temné, pouze se zavřeným otvorem pro okno a krbem pro noční osvětlení.[57]

Washington poskytoval svým zotročeným lidem maximálně každý pád přikrývku, kterou používali k vlastnímu ložnímu prádlu a kterou museli používat ke shromažďování listí pro podestýlku pro hospodářská zvířata.[58] Otroci na odlehlých farmách dostávali každý rok základní sadu oděvů, srovnatelnou s oděvy vydávanými na jiných plantážích ve Virginii. Otroci spali a pracovali ve svých šatech a nechali je strávit mnoho měsíců v oděvech, které byly nošené, roztrhané a potrhané.[59] Domácí otroci v hlavní rezidenci, kteří přicházeli do pravidelného kontaktu s návštěvníky, byli lépe oblečení; komorníci, číšníci a služebníci byli oblečeni do livrej založené na třídílném obleku džentlmena z 18. století a služky dostaly kvalitnější oblečení než jejich protějšky v polích.[60]

Washington si přál, aby jeho zotročení pracovníci byli dostatečně krmení, ale už ne.[61] Každému zotročenému bylo poskytnuto základní denní stravné ve výši jednoho litru USA (0,95 l) nebo více kukuřičná mouka, až osm uncí (230 g) sledě a občas trochu masa, poměrně typická dávka pro zotročenou populaci ve Virginii, která byla adekvátní z hlediska kalorického požadavku pro mladého muže, který pracoval se středně těžkou zemědělskou prací, ale měl nedostatek výživy.[62] Základní dávka byla doplněna vlastními silami zotročených lidí, lovem (pro něž byly některým povoleny zbraně) a odchytem zvěře. Pěstovali si vlastní zeleninu na malých zahradních pozemcích, které měli povoleno udržovat ve svém volném čase, na kterém také chovali drůbež.[63]

Washington často uváděl zotročené lidi při jeho návštěvách jiných statků a je pravděpodobné, že jeho vlastní zotročení pracovníci byli podobně odměněni návštěvníky Mount Vernon. Zotročení lidé občas vydělávali peníze běžnou prací nebo poskytováním konkrétních služeb - například Washington v roce 1775 odměnil tři své vlastní zotročené penězi za dobrou službu, zotročená osoba dostala poplatek za péči o klisnu, která byla chována 1798 a kuchař Herkules dobře profitoval z prodeje kupónů z prezidentské kuchyně.[64] Zotročení lidé také vydělávali peníze ze svého vlastního úsilí, prodejem do Washingtonu nebo na trhu v Alexandrie jídlo, které ulovili nebo vypěstovali, a drobné předměty, které vyrobili.[65] Výtěžek použili na nákup lepšího oblečení, domácích potřeb a doplňků, jako je mouka, vepřové maso, whisky, čaj, káva a cukr z Washingtonu nebo z obchodů v Alexandrii.[66]

Rodina a komunita

Ačkoli zákon neuznával manželství s otroky, Washington to dělal a do roku 1799 byly asi dvě třetiny zotročené dospělé populace na hoře Vernon vdané.[67] Aby se minimalizoval čas ztracený při vstupu na pracoviště a tím se zvýšila produktivita, byli zotročení lidé ubytováni na farmě, na které pracovali. Kvůli nerovnému rozdělení mužů a žen na pěti farmách si zotročení lidé často našli partnery na různých farmách a v jejich každodenním životě byli manželé běžně odděleni od svých manželek a dětí. Washington občas zrušil rozkazy, aby nerozdělil manžele, ale historika Henry Wiencek píše: „jako obecná praxe řízení [Washington] institucionalizovala lhostejnost ke stabilitě zotročených rodin.“[68] Pouze třicet šest z devadesáti šesti vdaných otroků na hoře Vernon v roce 1799 žilo společně, zatímco třicet osm mělo manžely, kteří žili na samostatných farmách, a dvacet dva měli manžele, kteří žili na jiných plantážích.[69] Důkazy naznačují, že páry, které byly od sebe odděleny, během týdne pravidelně nenavštěvovaly, což vedlo ke stížnostem Washingtonu, že zotročení lidé byli po takové „noční chůzi“ příliš vyčerpaní na to, aby jako hlavní čas těchto rodin zůstali sobotní noci, neděle a svátky. mohli trávit společně.[70] Navzdory stresu a úzkosti způsobené touto lhostejností ke stabilitě rodiny - dozorce jednou napsal, že odloučení rodin „se jim zdá být smrtí“ - manželství bylo základem, na němž si zotročená populace vytvořila vlastní komunitu, a dlouhověkost v nich. odbory nebyly neobvyklé.[71][72]

Velké rodiny, které pokrývaly více generací, spolu s jejich doprovodnými manželstvími, byly součástí zotročeného procesu budování komunity, který přesahoval vlastnictví. Například hlavní tesař Washingtonu Isaac žil se svou ženou Kitty, mléčnou služebnou s otroky, v Mansion House Farm. Pár měl devět dcer ve věku od šesti do dvaceti sedmi v roce 1799 a manželství čtyř z těchto dcer rozšířilo rodinu na další farmy uvnitř i vně panství Mount Vernon a vyprodukovalo tři vnoučata.[73][74] Děti se narodily do otroctví, jejich vlastnictví bylo určeno vlastnictvím jejich matek.[75] Hodnota spojená s narozením zotročeného dítěte, pokud byla vůbec uvedena, je uvedena v týdenní zprávě jednoho dozorce, který uváděl: „Zvyšte 9 jehňat a 1 dítě mužského pohlaví Lynnas.“ Nové matky dostaly novou přikrývku a tři až pět týdnů lehkých povinností k uzdravení. Dítě zůstalo se svou matkou na pracovišti.[76] Starší děti, z nichž většina žila v domácnostech s jedním rodičem, kde matka pracovala od rána do soumraku, vykonávaly malé rodinné práce, ale jinak jim bylo ponecháno hraní bez dozoru, dokud nedosáhly věku, kdy mohly začít pracovat Washington, obvykle někde mezi jedenácti a čtrnácti lety.[77] V roce 1799 bylo téměř šedesát procent otrokářské populace mladší devatenáct let a téměř třicet pět procent méně než devět.[73]

Existují důkazy, že zotročení lidé předávali své africké kulturní hodnoty prostřednictvím vyprávění příběhů, mezi nimi i příběhů o Br'er Rabbit které by se svým původem v Africe a příběhy bezmocného jedince triumfujícího vtipem a inteligencí nad mocnou autoritou rezonovaly u zotročeného.[78] Afričtí otroci si s sebou přinesli některé náboženské rituály svého domova předků a na jedné z farem v Mount Vernon existuje neregistrovaná tradice vúdú.[79] Ačkoli otrokářský stav znemožňoval dodržovat Pět pilířů islámu, některá jména otroků prozrazují muslimský kulturní původ.[80] Anglikáni Oslovili americké otroky ve Virginii a je známo, že někteří z zotročené populace Mount Vernon byli pokřtěni před tím, než Washington získal majetek. V historických záznamech z roku 1797 existují důkazy, s nimiž měla zotročená populace na hoře Vernon kontakty Křtitelé, Metodisté a Kvakeri.[81] Tři náboženství prosazovala zrušení, vzbuzovala naději na svobodu zotročených, a sbor Alexandrijské baptistické církve, založený v roce 1803, zahrnoval zotročené lidi, které dříve vlastnil Washington.[82]

Mulattoes a interracial sex

| Externí video | |

|---|---|

V roce 1799 jich bylo asi dvacet mulat (smíšená rasa) zotročil lidi na hoře Vernon. Neexistují však věrohodné důkazy o tom, že by George Washington využil sexuální výhody jakéhokoli otroka.[83][84][C]

Pravděpodobnost otcovských vztahů mezi zotročenými a najatými bílými dělníky naznačují některá příjmení: Betty a Tom Davis, pravděpodobně děti Thomase Davise, bílého tkalce na hoře Vernon v 60. letech 20. století; George Young, pravděpodobně syn muže stejného jména, který byl úředníkem v Mount Vernon v roce 1774; a soudkyně a její sestra Delphy, dcery Andrewa Judge, indenturovaného krejčího na hoře Vernon v 70. a 80. letech 20. století.[87] Existují důkazy, které naznačují, že bílí dozorci - pracující v těsné blízkosti zotročených lidí pod stejným náročným pánem a fyzicky a sociálně izolovaní od své vlastní vrstevnické skupiny, situace, která některé vedla k pití - se oddávali sexuálním vztahům s zotročenými lidmi, nad nimiž dohlíželi .[88] Zdálo se, že někteří bílí návštěvníci Mount Vernon očekávali, že zotročené ženy budou poskytovat sexuální služby.[89] Živé uspořádání nechávalo některé zotročené ženy samy a zranitelné a historička výzkumu Mount Vernon Mary V. Thompson píše, že vztahy „mohly být výsledkem vzájemné přitažlivosti a náklonnosti, velmi skutečných demonstrací moci a kontroly nebo dokonce cvičení manipulace autoritativní osoby ".[90]

Odpor

Ačkoli část zotročené populace na Mount Vernon začala pociťovat loajalitu vůči Washingtonu, odpor, který projevilo značné procento z nich, je naznačen častými komentáři Washingtonu k „podvodům“ a „starým trikům“.[91][92] Nejběžnějším činem odporu byla krádež, která byla tak běžná, že Washington na ni udělal přirážky jako součást běžného plýtvání. Potraviny se kradly jak k doplnění dávek, tak k prodeji a Washington věřil, že prodej nástrojů je dalším zdrojem příjmů pro zotročené lidi. Protože se látky a oděvy běžně kradly, Washington požadoval, aby švadleny před vydáním dalšího materiálu předvedly výsledky své práce a zbytky šrotu. Ovce byly před stříháním omyty, aby se zabránilo krádeži vlny, a skladovací prostory byly drženy zamčené a klíče byly ponechány důvěryhodným osobám.[93] V roce 1792 Washington nařídil utracení psů zotročených lidí, o nichž se domníval, že jsou používány při spoustě krádeží hospodářských zvířat, a rozhodl, že zotročení lidé, kteří chovali psy bez povolení, mají být „přísně potrestáni“ a jejich psi pověšeni.[94]

Dalším prostředkem, kterým zotročení lidé vzdorovali, což bylo prakticky nemožné dokázat, byla předstírání nemoci. V průběhu let se Washington stával skeptičtějším ohledně nepřítomnosti kvůli nemoci u své zotročené populace a znepokojen péčí nebo schopností jeho dozorců rozpoznat skutečné případy. V letech 1792 až 1794, kdy byl Washington mimo Mount Vernon jako prezident, se počet dní ztracených kvůli nemoci zvýšil desetkrát ve srovnání s rokem 1786, kdy pobýval na Mount Vernon a byl schopen osobně kontrolovat situaci. V jednom případě Washington podezříval zotročenou osobu, že se často po desetiletí vyhýbá práci úmyslným sebepoškozováním.[95]

Otroci prosazovali určitou samostatnost a frustrovali Washington tempem a kvalitou jejich práce.[96] V roce 1760 Washington poznamenal, že čtyři z jeho tesařů zčtyřnásobili produkci dřeva pod jeho osobním dohledem.[97] O třicet pět let později popsal své tesaře jako „nečinnou ... sadu darebáků“, kterým by dokončení práce na Mount Vernon, která se dělala za dva nebo tři dny v Philadelphie. Když šla Martha pryč, výkon švadlen klesl a přadleny zjistily, že se mohou uvolnit tím, že proti ní budou hrát na dozorce.[98] Nástroje byly pravidelně ztraceny nebo poškozeny, čímž se zastavila práce, a Washington zoufal z používání inovací, které by mohly zlepšit efektivitu, protože věřil, že zotročení pracovníci jsou příliš nemotorní na to, aby mohli obsluhovat nové použité stroje.[99]

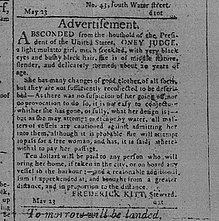

Nejvýraznějším činem odporu byl útěk a mezi lety 1760 a 1799 tak učinilo nejméně čtyřicet sedm zotročených lidí pod kontrolou Washingtonu.[100] Sedmnáct z nich, čtrnáct mužů a tři ženy, uprchlo k britské válečné lodi, která zakotvila v Řeka Potomac poblíž Mount Vernon v roce 1781.[101] Obecně platí, že nejlepší šance na úspěch měli afroameričtí zotročení lidé druhé nebo třetí generace, kteří měli dobrou angličtinu, měli dovednosti, které by jim umožňovaly podporovat sebe jako svobodné lidi a byli dostatečně v těsném kontaktu se svými pány, aby získali speciální privilegia. Soudce, obzvláště talentovaná švadlena, tedy Hercules unikl v letech 1796 a 1797 a unikl opětovnému získání.[102] Washington bral znovuzískání uprchlíků vážně a ve třech případech byli zotročení lidé, kteří utekli, v Západní Indii po opětovném odprodání rozprodáni, což ve skutečnosti v těchto drsných podmínkách tam zotročení vydržel.[103][104][105]

Řízení

Jessie MacLeod

Spolupracovník kurátor

Mount Washington Vernon George Washingtona[106]

Washington využil odměnu i trest k podpoře disciplíny a produktivity ve své zotročené populaci.[107] V jednom případě navrhl, aby „napomenutí a rady“ byly účinnější než „další náprava“, a příležitostně apeloval na pocit hrdosti zotročené osoby, aby podpořil lepší výkon. Odměny v podobě kvalitnějších přikrývek a oděvní látky dostaly „nejzasloužilejší“ a existují příklady odměn v hotovosti za dobré chování.[108] V zásadě se postavil proti použití bičů, ale považoval tuto praxi za nutné zlo a schválil její příležitostné použití, obecně jako poslední možnost, na zotročené lidi, muže i ženy, pokud podle jeho slov „nečiní“ jejich povinnost spravedlivými prostředky “.[107] Existují zprávy o tom, že tesaři byli zbičováni v roce 1758, kdy dozorce „viděl chybu“, o zotročené osobě zvané Jemmy, která byla zbičována za krádež kukuřice a útěku v roce 1773, a o švadleně jménem Charlotte, která byla v roce 1793 zbičována dozorcem „odhodlaná Snižte ducha nebo ji stáhněte za záda “pro drzost a odmítnutí pracovat.[109][110]

Washington považoval „vášeň“, s níž jeden z jeho dozorců spravoval bičování, za kontraproduktivní, a Charlotteův protest, že nebyla zbičována čtrnáct let, naznačuje frekvenci, s jakou byl fyzický trest používán.[111][112] Bičování bylo po kontrole kontrolováno dozorci, což systém vyžadoval Washington, aby zajistil, že zotročení lidé budou ušetřeni rozmarů a extrémních trestů. Sám Washington neztratil zotročené lidi, ale příležitostně v záblesku nálady vybuchl slovním zneužíváním a fyzickým násilím, když selhali tak, jak očekával.[113][d] Současníci obecně popisovali, že Washington má klidné chování, ale existuje několik zpráv od těch, kteří ho znali soukromě, kteří zmiňují jeho povahu. Jeden napsal, že „v soukromí a zejména u jeho zaměstnanců někdy vypuklo jeho násilí“. Další uvedl, že zaměstnanci Washingtonu „vypadali, že sledují jeho oko a předvídají každé jeho přání; pohled tedy odpovídal příkazu“.[115] Hrozby degradace na terénní práce, tělesné tresty a přeprava do Západní Indie byly součástí systému, kterým ovládal svou zotročenou populaci.[103][116]

Vývoj postojů Washingtonu

Počáteční názory Washingtonu na otroctví se nelišily od žádné Virginie květináč času.[51] O instituci neprokázal žádné morální výčitky a během těchto let označoval otroky za „druh majetku“, jako by to později v životě, když upřednostňoval zrušení.[117] Ekonomika otroctví vyvolala ve Washingtonu první pochybnosti o této instituci, což znamenalo začátek pomalého vývoje v jeho přístupu k ní. Do roku 1766 přešel z podnikání na intenzivní pěstování tabáku na méně náročné pěstování obilnin. Jeho otroci byli zaměstnáni na rozmanitější úkoly, které vyžadovaly více dovedností, než od nich vyžadovalo pěstování tabáku; stejně jako pěstování obilí a zeleniny se používali při pasení, spřádání, tkaní a tesařství skotu. Tento přechod zanechal ve Washingtonu přebytek otroků a odhalil mu neúčinnost systému otrocké práce.[118][119]

Existuje jen málo důkazů, že Washington vážně zpochybňoval etiku otroctví před revolucí.[119] In the 1760s he often participated in tavern lotteries, events in which defaulters' debts were settled by raffling off their assets to a high-spirited crowd.[120] In 1769, Washington co-managed one such lottery in which fifty-five slaves were sold, among them six families and five females with children. The more valuable married males were raffled together with their wives and children; less valuable slaves were separated from their families into different lots. Robin and Bella, for example, were raffled together as husband and wife while their children, twelve-year-old Sukey and seven-year-old Betty, were listed in a separate lot. Only chance dictated whether the family would remain together, and with 1,840 tickets on sale the odds were not good.[121]

| Externí video | |

|---|---|

Historik Henry Wiencek concludes that the repugnance Washington felt at this cruelty in which he had participated prompted his decision not to break up slave families by sale or purchase, and marks the beginning of a transformation in Washington's thinking about the morality of slavery.[122] Wiencek writes that in 1775 Washington took more slaves than he needed rather than break up the family of a slave he had agreed to accept in payment of a debt.[123] Historici Philip D. Morgan and Peter Henriques[E] are skeptical of Wiencek's conclusion and believe there is no evidence of any change in Washington's moral thinking at this stage. Morgan writes that in 1772, Washington was "all business" and "might have been buying livestock" in purchasing more slaves who were to be, in Washington's words, "strait Limb'd, & in every respect strong & likely, with good Teeth & good Countenance". Morgan gives a different account of the 1775 purchase, writing that Washington resold the slave because of the slave's resistance to being separated from family and that the decision to do so was "no more than the conventional piety of large Virginia planters who usually said they did not want to break up slave families – and often did it anyway".[125][126]

americká revoluce

From the late 1760s, Washington became increasingly radicalized against the North American colonies' subservient status within the Britská říše.[127] In 1774 he was a key participant in the adoption of the Fairfax řeší which, alongside the assertion of colonial rights, condemned the transatlantic slave trade on moral grounds.[128][119] Washington was a signatory to that entire document, and thus publicly endorsed clause 17 "declaring our earnest wishes to see an entire stop forever put to such wicked, cruel, and unnatural trade."[129]

He began to express the growing rift with Velká Británie in terms of slavery, stating in the summer of 1774 that the British authorities were "endeavouring by every piece of Art & despotism to fix the Shackles of Slavry [sic ]" upon the colonies. Two years later, on taking command of the Kontinentální armáda at Cambridge at the start of the Americká revoluční válka, he wrote in orders to his troops that "it is a noble Cause we are engaged in, it is the Cause of virtue and mankind...freedom or Slavery must be the result of our conduct."[130] The hypocrisy or paradox inherent in slave owners characterizing a war of independence as a struggle for their own freedom from slavery was not lost on the British writer Samuel Johnson, who asked, "How is it that we hear the loudest yelps for liberty among the drivers of Negroes?"[131][132] As if answering Johnson, Washington wrote to a friend in August 1774, "The crisis is arrived when we must assert our rights, or submit to every imposition that can be heaped upon us, till custom and use shall make us tame and abject slaves, as the blacks we rule over with such arbitrary sway."[133]

Washington shared the common Southern concern about arming African Americans, enslaved or free, and initially refused to accept either into the ranks of the Continental Army. He reversed his position on free African Americans when the royal governor of Virginia, Lord Dunmore, vydal a proklamace in November 1775 offering freedom to rebel-owned slaves who enlisted in the British forces. Three years later and facing acute manpower shortages, Washington approved a Rhode Island initiative to raise a battalion of African-American soldiers[134][135]

Washington gave a cautious response to a 1779 proposal from his young aide John Laurens for the recruitment of 3,000 South Carolinian enslaved workers who would be rewarded with emancipation. He was concerned that such a move would prompt the British to do the same, leading to an arms race in which the Americans would be at a disadvantage, and that it would promote discontent among those who remained enslaved.[136][137][F] In 1780, he suggested to one of his commanders the integration of African-American recruits "to abolish the name and appearance of a Black Corps."[141]

During the war, some 5,000 African Americans served in a Continental Army that was more integrated than any American force before the vietnamská válka, and another 1,000 served on American warships. They represented less than three percent of all American forces mobilized, though in 1778 they provided as much as 13% of the Continental Army.[142][143] By the end of the war African-Americans were serving alongside whites in virtually all units other than those raised in the deep south.[141][144]

The first indication of a shift in Washington's thinking on slavery appears during the war, in correspondence of 1778 and 1779 with Lund Washington, who managed Mount Vernon in Washington's absence.[145] In the exchange of letters, a conflicted Washington expressed a desire "to get quit of Negroes", but made clear his reluctance to sell them at a public venue and his wish that "husband and wife, and Parents and children are not separated from each other".[146] His determination not to separate families became a major complication in his deliberations on the sale, purchase and, in due course, emancipation of his own slaves.[147] His restrictions put Lund in a difficult position with two female slaves he had already all but sold in 1778, and Lund's irritation was evident in his request to Washington for clear instructions.[148] Despite Washington's reluctance to break up families, there is little evidence that moral considerations played any part in his thinking at this stage. He sought to liberate himself from an economically unviable system, not to liberate his slaves. They were still a property from which he expected to profit. During a period of severe wartime depreciation, the question was not whether to sell his enslaved people, but when, where, and how best to sell them. Lund sold nine enslaved including the two females, in January 1779.[149][150][151]

Washington's actions at the war's end reveal little in the way of antislavery inclinations. He was anxious to recover his own slaves, and refused to consider compensation for the upwards of 80,000 formerly enslaved people evacuated by the British, demanding without success that the British respect a clause in the Preliminary Articles of Peace which he regarded as requiring the return of all slaves and other American property even if the British had purported to free some of those slaves.[152][153][154] Před resigning his commission in 1783, Washington took the opportunity to give his opinion on the challenges that threatened the existence of the new nation, in his Circular to the States. Že oběžník inveighed against “local prejudices” but explicitly declined to name any of them, “leaving the last to the good sense and serious consideration of those immediately concerned.”[153][155]

Confederation years

Emancipation became a major issue in Virginia after liberalization in 1782 of the law regarding osvobození, which is the act of an owner freeing his slaves. Before 1782, a manumission had required obtaining consent from the state legislature, which was arduous and rarely granted.[156] After 1782, inspired by the rhetoric that had driven the revolution, it became popular to free slaves. The free African-American population in Virginia rose from some 3,000 to more than 20,000 between 1780 and 1800; the 1800 sčítání lidu Spojených států tallied about 350,000 slaves in Virginia, and the proslavery interest re-asserted itself around that time.[157][158][159] The historian Kenneth Morgan writes, "...the revolutionary war was the crucial turning-point in [Washington's] thinking about slavery. After 1783...he began to express inner tensions about the problem of slavery more frequently, though always in private..."[160] Although Philip Morgan identifies several turning points and believes no single one was pivotal,[G] most historians agree the Revolution was central to the evolution of Washington's attitudes on slavery.[164][165] It is likely that revolutionary rhetoric about the rights of men, the close contact with young antislavery officers who served with Washington – such as Laurens, the Markýz de Lafayette a Alexander Hamilton – and the influence of northern colleagues were contributory factors in that process.[166][167][h]

Washington was drawn into the postwar abolitionist discourse through his contacts with antislavery friends, their transatlantic network of leading abolitionists and the literature produced by the antislavery movement,[170] though he was reluctant to volunteer his own opinion on the matter and generally did so only when the subject was first raised with him.[160] At his death, Washington's extensive library included at least seventeen publications on slavery. Six of them had been collated into an expensively bound volume titled Tracts on Slavery, indicating that he attached some importance to that selection. Five of the six were published in or after 1788.[i] All six shared common themes that slaves first had to be educated about the obligations of liberty before they could be emancipated, a belief Washington is reported to have expressed himself in 1798, and that abolition should be realized by a gradual legislative process, an idea that began to appear in Washington's correspondence during the Confederation period.[172][173]

Washington was not impressed by what Dorothy Twohig – a former editor-in-chief of The Washington Papers – described as the "imperious demands" and "evangelical piety" of Quaker efforts to advance abolition, and in 1786 he complained about their "tamper[ing] with & seduc[ing]" slaves who "are happy & content to remain with their present masters".[174][175] Only the most radical of abolitionists called for immediate emancipation. The disruption to the labor market and the care of the elderly and infirm would have created enormous problems. Large numbers of unemployed poor, of whatever color, was a cause for concern in 18th-century America, to the extent that expulsion and foreign resettlement was often part of the discourse on emancipation.[176] A sudden end to slavery would also have caused a significant financial loss to slaveowners whose human property represented a valuable asset. Gradual emancipation was seen as a way of mitigating against such a loss and reducing opposition from those with a financial self-interest in maintaining slavery.[177]

In 1783, Lafayette proposed a joint venture to establish an experimental settlement for freed slaves which, with Washington's example, "might render it a general practise", but Washington demurred. As Lafayette forged ahead with his plan, Washington offered encouragement but expressed concern in 1786 about "much inconvenience and mischief" an abrupt emancipation might generate, and he gave no tangible support to the idea.[150][178][j]

Washington expressed support for emancipation legislation to prominent Methodists Thomas Coke a Francis Asbury in 1785, but declined to sign their petition which (as Coke put it) asked "the General Assembly of Virginia, to pass a law for the immediate or gradual emancipation of all the slaves".[181][182][183] Washington privately conveyed his support for such legislation to most of the great men of Virginia,[184][181] and promised to comment publicly on the matter by letter to the Virginia Assembly if the Assembly would begin serious deliberation about the Methodists' petition.[185][183] The historian Lacy Ford writes that Washington may have dissembled: "In all likelihood, Washington was honest about his general desire for gradual emancipation but dissembled about his willingness to speak publicly on its behalf; the Mount Vernon master almost certainly reasoned that the legislature would table the petition immediately and thus release him from any obligation to comment publicly on the matter." The measure was rejected without any dissent in the Virginia House of Delegates, because abolitionist legislators quickly backed down rather than suffer inevitable defeat.[181][184][185] Washington wrote in despair to Lafayette: "Some petitions were presented to the Assembly at its last session for the abolition of slavery, but they could scarce obtain a reading."[183] James Thomas Flexner ’s interpretation is somewhat different from Lacy Ford’s: "Washington was willing to back publicly the Methodists' petition for gradual emancipation if the proposal showed the slightest possibility of being given consideration by the Virginia legislature."[183] Flexner adds that, if Washington had been more audacious in pursuing emancipation in Virginia, then "he undoubtedly would have failed to achieve the end of slavery, and he would certainly have made impossible the role he played in the Constitutional Convention and the Presidency."[186]

Henriques identifies Washington's concern for the judgement of posterity as a significant factor in Washington's thinking on slavery, writing, "No man had a greater desire for secular immortality, and [Washington] understood that his place in history would be tarnished by his ownership of slaves."[187] Philip Morgan similarly identifies the importance of Washington's driving ambition for fame and public respect as a man of honor;[167] in December 1785, the Quaker and fellow Virginian Robert Pleasants "[hit] Washington where it hurt most", Morgan writes, when he told Washington that to remain a slaveholder would forever tarnish his reputation.[188][k] In correspondence the next year with Maryland politician John Francis Mercer, Washington expressed "great repugnance" at buying slaves, stated that he would not buy any more "unless some peculiar circumstances should compel me to it" and made clear his desire to see the institution of slavery ended by a gradual legislative process.[193][194] He expressed his support for abolitionist legislation privately, but widely,[195] sharing those views with leading Virginians,[183] and with other leaders including Mercer and founding father Robert Morris of Pennsylvania to whom Washington wrote:[196]

I can only say that there is not a man living who wishes more sincerely than I do, to see a plan adopted for the abolition of it – but there is only one proper and effectual mode by which it can be accomplished, and that is by Legislative authority: and this, as far as my suffrage will go, shall never be wanting.

Washington still needed labor to work his farms, and there was little alternative to slavery. Hired labor south of Pennsylvania was scarce and expensive, and the Revolution had cut off the supply of indentured servants and convict labor from Great Britain.[197][37] Washington significantly reduced his slave purchases after the war, though it is not clear whether this was a moral or practical decision; he repeatedly stated that his inventory and its potential progeny were adequate for his current and foreseeable needs.[198][199] Nevertheless, he negotiated with John Mercer to accept six slaves in payment of a debt in 1786 and expressed to Henry Lee a desire to purchase a bricklayer the next year.[175][19][l] In 1788, Washington acquired thirty-three slaves from the estate of Bartoloměj Dandridge in settlement of a debt and left them with Dandridge's widow on her estate at Pamocra, New Kent County, Virginia.[204][205] Later the same year, he declined a suggestion from the leading French abolitionist Jacques Brissot to form and become president of an abolitionist society in Virginia, stating that although he was in favor of such a society and would support it, the time was not yet right to confront the issue.[206] Historian James Flexner has written that, generally speaking, "Washington limited himself to stating that, if an authentic movement toward emancipation could be started in Virginia, he would spring to its support. No such movement could be started."[207]

Creation of the U.S. Constitution

Washington presided over the Ústavní shromáždění in 1787, during which it became obvious how explosive the slavery issue was, and how willing the antislavery faction was to accept the preservation of this oppressive institution to ensure national unity and the establishment of a strong federal government. The Constitution allowed but did not require the preservation of slavery, and it deliberately avoided use of the word "slave" which could have been interpreted as authorizing the treatment of human beings as property throughout the country.[208] Each state was allowed to keep it, change it, or eliminate it as they wished, though Congress could make various policies that would affect this decision in each state. As of 1776, slavery was legal in all 13 colonies, but by Washington's death in December 1799 there were eight free states and nine slave states, and that split was considered entirely constitutional.[209]

The support of the southern states for the new constitution was secured by granting them concessions that protected slavery, including the Klauzule na útěku, plus clauses that promised Congress would not prohibit the transatlantic slave trade for twenty years, and that empowered (but did not require) Congress to authorize suppression of insurrections such as slave rebellions.[210][211] The Constitution also included the Kompromis ze tří pětin which cut both ways: for purposes of taxation and representation, three out of every five slaves would be counted, which meant that each slave state would have to pay less taxes but would also have less representation in Congress than if every slave was counted.[212] After the convention, Washington's support was critical for getting the states to ratify the document.[213]

Presidential years

Statement attributed to George Washington that appears in the notebook of David Humphreys, c.1788/1789[214]

Washington's preeminent position ensured that any actions he took with regard to his own slaves would become a statement in a national debate about slavery that threatened to divide the country. Wiencek suggests Washington considered making precisely such a statement on taking up the presidency in 1789. A passage in the notebook of Washington's biographer David Humphreys[m] dated to late 1788 or early 1789 recorded a statement that resembled the emancipation clause in Washington's will a decade later. Wiencek argues the passage was a draft for a public announcement Washington was considering in which he would declare the emancipation of some of his slaves. It marks, Wiencek believes, a moral epiphany in Washington's thinking, the moment he decided not only to emancipate his slaves but also to use the occasion to set the example Lafayette had urged in 1783.[216] Other historians dispute Wiencek's conclusion; Henriques and Joseph Ellis concur with Philip Morgan's opinion that Washington experienced no epiphanies in a "long and hard-headed struggle" in which there was no single turning point. Morgan argues that Humphreys' passage is the "private expression of remorse" from a man unable to extricate himself from the "tangled web" of "mutual dependency" on slavery, and that Washington believed public comment on such a divisive subject was best avoided for the sake of national unity.[217][218][126][n]

Jako prezident

Washington took up the presidency at a time when revolutionary sentiment against slavery was giving way to a resurgence of proslavery interests. No state considered making slavery an issue during the ratification of the new constitution, southern states reinforced their slavery legislation and prominent antislavery figures were muted about the issue in public. Washington understood there was little widespread organized support for abolition.[222] He had a keen sense both of the fragility of the fledgling Republic and of his place as a unifying figure, and he was determined not to endanger either by confronting an issue as divisive and entrenched as slavery.[223][224]

He was president of a government that provided materiel and financial support for French efforts to suppress the Saint Domingue slave revolt in 1791, and implemented the proslavery Zákon o uprchlém otrokovi z roku 1793.[225][226][227]

On the anti-slavery side of the ledger, in 1789 he signed a reenactment of the Severozápadní vyhláška which freed any new slaves brought after 1787 into a vast expanse of federal territory, except for slaves escaping from slave states.[228][229] Washington also signed into law the Zákon o obchodu s otroky z roku 1794 that banned the involvement of American ships and American exports in the international slave trade.[230] Moreover, according to Washington biographer James Thomas Flexner, Washington as President weakened slavery by favoring Hamilton's economic plans přes Jefferson's agrarian economics.[207]

Washington never spoke publicly on the issue of slavery during his eight years as president, nor did he respond to, much less act upon, any of the antislavery petitions he received. He described a 1790 Quaker petition to Kongres urging an immediate end to the slave trade as "an illjudged piece of business" that "occasioned a great waste of time", although historian Paul F. Boller has observed that Congress extensively debated that petition only to conclude it had no power to do anything about it, so "The Quaker Memorial may have been a waste of time so far as immediate practical results were concerned."[231]

Late in his presidency, Washington told his státní tajemník, Edmund Randolph, that in the event of a confrontation between North and South, he had "made up his mind to remove and be of the Northern" (i.e. leave Virginia and move up north).[232] In 1798, he imagined just such a conflict when he said, "I can clearly foresee that nothing but the rooting out of slavery can perpetuate the existence of our union."[233][173] But there is no indication Washington ever favored an immediate rather than gradual end to slavery. His abolitionist aspirations for the nation centered around the hope that slavery would disappear naturally over time with the prohibition of slave imports in 1808, the earliest date such legislation could be passed as agreed at the Constitutional Convention.[176][234] Indeed, the dying out of slavery remained possible, until Eli Whitney vynalezl cotton gin in 1793 which led within five years to a vastly greater demand for slave labor.[235]

As Virginia farmer

As well as political caution, economic imperatives remained an important consideration with regard to Washington's personal position as a slaveholder and his efforts to free himself from his dependency on slavery.[236][163] He was one of the largest debtors in Virginia at the end of the war,[237] and by 1787 the business at Mount Vernon had failed to make a profit for more than a decade. Persistently poor crop yields due to pestilence and poor weather, the cost of renovations at his Mount Vernon residence, the expense of entertaining a constant stream of visitors, the failure of Lund to collect rent from Washington's tenant farmers and wartime depreciation all helped to make Washington cash poor.[238][239]

George Washington to Robert Lewis, August 17, 1799[240]

The overheads of maintaining a surplus of slaves, including the care of the young and elderly, made a substantial contribution to his financial difficulties.[241][199] In 1786, the ratio of productive to non-productive slaves was approaching 1:1, and the c. 7,300-acre (3,000 ha) Mount Vernon estate was being operated with 122 working slaves. Although the ratio had improved by 1799 to around 2:1, the Mount Vernon estate had grown by only 10 percent to some 8,000 acres (3,200 ha) while the working slave population had grown by 65 percent to 201. It was a trend that threatened to bankrupt Washington.[242][243] The slaves Washington had bought early in the development of his business were beyond their prime and nearly impossible to sell, and from 1782 Virginia law made slaveowners liable for the financial support of slaves they freed who were too young, too old or otherwise incapable of working.[244][245]

During his second term, Washington began planning for a retirement that would provide him "tranquillity with a certain income".[246] In December 1793, he sought the aid of the British agriculturalist Arthur Young in finding farmers to whom he would lease all but one of his farms, on which his slaves would then be employed as laborers.[247][248] The next year, he instructed his secretary Tobias Lear to sell his western lands, ostensibly to consolidate his operations and put his financial affairs in order. Washington concluded his instructions to Lear with a private passage in which he expressed repugnance at owning slaves and declared that the principal reason for selling the land was to raise the finances that would allow him to liberate them.[236][249] It is the first clear indication that Washington's thinking had shifted from selling his slaves to freeing them.[246] In November the same year (1794), Washington declared in a letter to his friend and neighbor Alexander Spotswood: "Were it not then, that I am principled agt. [sic ] selling Negroes, as you would Cattle in the market, I would not, in twelve months from this date, be possessed of one as a slave."[250][251]

In 1795 and 1796, Washington devised a complicated plan that involved renting out his western lands to tenant farmers to whom he would lease his own slaves, and a similar scheme to lease the dower slaves he controlled to Dr. David Stuart for work on Stuart's Eastern Shore plantation. This plan would have involved breaking up slave families, but it was designed with an end goal of raising enough finances to fund their eventual emancipation (a detail Washington kept secret) and prevent the Custis heirs from permanently splitting up families by sale.[252][253][Ó]

None of these schemes could be realized because of his failure to sell or rent land at the right prices, the refusal of the Custis heirs to agree to them and his own reluctance to separate families.[255][256] Wiencek speculates that, because Washington gave such serious consideration to freeing his slaves knowing full well the political ramifications that would follow, one of his goals was to make a public statement that would sway opinion towards abolition.[257] Philip Morgan argues that Washington freeing his slaves while President in 1794 or 1796 would have had no profound effect, and would have been greeted with public silence and private derision by white southerners.[258]

Wiencek writes that if Washington had found buyers for his land at what seemed like a fair price, this plan would have ultimately freed "both his own and the slaves controlled by Martha’s family",[259] and to accomplish this goal Washington would "yield up his most valuable remaining asset, his western lands, the wherewithal for his retirement."[260] Ellis concludes that Washington prioritized his own financial security over the freedom of the enslaved population under his control, and writes, on Washington's failure to sell the land at prices he thought fair, "He had spent a lifetime acquiring an impressive estate, and he was extremely reluctant to give it up except on his terms."[261] In discussing another of Washington's plans, drawn up after he had written his will, to transfer enslaved workers to his estates in western Virginia, Philip Morgan writes, "Indisputably, then, even on the eve of his death, Washington was far from giving up on slavery. To the last, he was committed to making profits, even at the expense of the disruptions such transfers would indisputably have wrought on his slaves."[262]

As Washington subordinated his desire for emancipation to his efforts to secure financial independence, he took care to retain his slaves.[263] From 1791, he arranged for those who served in his personal retinue in Philadelphia while he was President to be rotated out of the state before they became eligible for emancipation after six months residence per Pennsylvanian law. Not only would Washington have been deprived of their services if they were freed, most of the slaves he took with him to Philadelphia were dower slaves, which meant that he would have had to compensate the Custis estate for the loss. Because of his concerns for his public image and that the prospect of emancipation would generate discontent among the slaves before they became eligible for emancipation, he instructed that they be shuffled back to Mount Vernon "under pretext that may deceive both them and the Public".[264]

Washington spared no expense in efforts to recover Hercules and Judge when they absconded. In Judge's case, Washington persisted for three years. He tried to persuade her to return when his agent eventually tracked her to New Hampshire, but refused to promise her freedom after his death; "However well disposed I might be to a gradual emancipation", he said, "or even to an entire emancipation of that description of People (if the latter was in itself practicable at this moment) it would neither be politic or just to reward unfaithfulness with a premature preference". Both Hercules and Judge eluded capture.[16] Washington's search for a new chef to replace Hercules in 1797 is the last known instance in which he considered buying a slave, despite his resolve "never to become the Master of another Slave by purchase"; in the end he chose to hire a white chef.[265]

Attitude to race

Historik Joseph Ellis writes that Washington did not favor the continuation of legal slavery, and adds "[n]or did he ever embrace the racial arguments for black inferiority that Jefferson advanced....He saw slavery as the culprit, preventing the development of diligence and responsibility that would emerge gradually and naturally after emancipation."[266] Other historians, such as Stuart Leibinger, agree with Ellis that, "Unlike Jefferson, Washington and Madison rejected innate black inferiority...."[267]

Historik James Thomas Flexner says that the charge of racism has come from historical revisionism and lack of investigation. Flexner has pointed out that slavery was, "Not invented for blacks, the institution was as old as history and had not, when Washington was a child, been officially challenged anywhere."[207]

Kenneth Morgan writes that, "Washington's engrained sense of racial superiority to African Americans did not lead to expressions of negrophobia...Yet Washington wanted his white workers to be housed away from the blacks at Mt. Vernon, believing that close racial intermixture was undesirable."[268] According to historian Albert Tillson, one reason why enslaved black people were lodged separately at Mount Vernon is because Washington felt that some white workers had habits that were "not good" (e.g., Tillson mentions instances of "interracial drinking" in the Chesapeake area), and another reason is that, Tillson reports, Washington "expected such accommodations would eventually disgust the white family."[269]

Philip Morgan writes that "The youthful Washington revealed prejudices toward blacks, quite natural for the day" and that "blackness, in his mind, was synonymous with uncivilized behaviour."[270] Washington's prejudices were not hard and fast; his retention of African-Americans in the Virginia Regiment contrary to the rules, his employment of African-American overseers, his use of African-American doctors and his praise for the "great poetical Talents" of the African-American poet Phillis Wheatley, who had lauded him in a poem in 1775, show that he recognized the skills and talents of African-Americans.[271] Historik Henry Wiencek rendered this judgment:[272]

“If you look at Washington’s will, he’s not conflicted over the place of African Americans at all,” Wiencek said in an interview. “From one end of his papers to the other, I looked for some sense of racism and found none, unlike Jefferson, who’s explicit on his belief in the inferiority of Black people. In his will, Washington authored a bill of rights for Black people and said they should be taught to read and write. They were Americans, with the right to live here, to be educated, and to work productively as free people.”

The views of Martha Washington about slavery and race were different from her husband's, and were less favorable to African Americans. For example, she said in 1795 that, "The Blacks are so bad in their nature that they have not the least grat[i]tude for the kindness that may be shewed to them." She refused to follow the example he set by emancipating his slaves, and instead she bequeathed the only slave she directly owned (named Elish) to her grandson.[273][274]

Posthumous emancipation

In July 1799, five months before his death, Washington wrote his will, in which he stipulated that his slaves should be freed. In the months that followed, he considered a plan to repossess tenancies in Berkeley a Frederick Counties and transferring half of his Mount Vernon slaves to work them. It would, Washington hoped, "yield more nett profit" which might "benefit myself and not render the [slaves'] condition worse", despite the disruption such relocation would have had on the slave families. The plan died with Washington on December 14, 1799.[275][p]

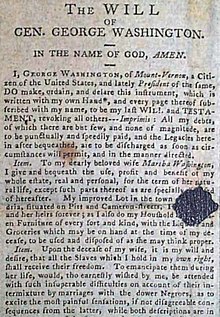

Washington's slaves were the subjects of the longest provisions in the 29-page will, taking three pages in which his instructions were more forceful than in the rest of the document. His valet, William Lee, was freed immediately and his remaining 123 slaves were to be emancipated o smrti Martha.[277][278] The deferral was intended to postpone the pain of separation that would occur when his slaves were freed but their spouses among the dower slaves remained in bondage, a situation which affected 20 couples and their children. It is possible Washington hoped Martha and her heirs who would inherit the dower slaves would solve this problem by following his example and emancipating them.[279][280][75] Those too old or infirm to work were to be supported by his estate, as mandated by state law.[281] In the late 1790s, about half the enslaved population at Mount Vernon was too old, too young, or too infirm to be productive.[282]

Washington went beyond the legal requirement to support and maintain younger slaves until adulthood, stipulating that those children whose education could not be undertaken by parents were to be taught reading, writing, and a useful trade by their masters and then be freed at the age of 25.[281] He forbade the sale or transportation of any of his slaves out of Virginia before their emancipation.[278] Including the Dandridge slaves, who were to be emancipated under similar terms, more than 160 slaves would be freed.[204][205] Although Washington was not alone among Virginian slaveowners in freeing their slaves, he was unusual among those doing it for doing it so late, after the post-revolutionary support for emancipation in Virginia had faded. He was also unusual for being the only slaveowning Founding Father to do so.[283] Other founders (if not founding otcové) freed their slaves, including John Dickinson a Caesar Rodney who both did so in Delaware.[284]

Následky

Any hopes Washington may have had that his example and prestige would influence the thinking of others, including his own family, proved to be unfounded. His action was ignored by southern slaveholders, and slavery continued at Mount Vernon.[285][286] Already from 1795, dower slaves were being transferred to Martha's three granddaughters as the Custis heirs married.[287] Martha felt threatened by being surrounded with slaves whose freedom depended on her death and freed her late husband's slaves on January 1, 1801.[288][q]

Able-bodied slaves were freed and left to support themselves and their families.[290] Within a few months, almost all of Washington's former slaves had left Mount Vernon, leaving 121 adult and working-age children still working the estate. Five freedwomen were listed as remaining: an unmarried mother of two children; two women, one of them with three children, married to Washington slaves too old to work; and two women who were married to dower slaves.[291] William Lee remained at Mount Vernon, where he worked as a shoemaker.[292] After Martha's death on May 22, 1802, most of the remaining dower slaves passed to her grandson, George Washington Parke Custis, to whom she bequeathed the only slave she held in her own name.[293]

There are few records of how the newly freed slaves fared.[294] Custis later wrote that "although many of them, with a view to their liberation, had been instructed in mechanic trades, yet they succeeded very badly as freemen; so true is the axiom, 'that the hour which makes man a slave, takes half his worth away'". The son-in-law of Custis's sister wrote in 1853 that the descendants of those who remained slaves, many of them now in his possession, had been "prosperous, contented and happy", while those who had been freed had led a life of "vice, dissipation and idleness" and had, in their "sickness, age and poverty", become a burden to his in-laws.[295] Such reports were influenced by the innate racism of the well-educated, upper-class authors and ignored the social and legal impediments that prejudiced the chances of prosperity for former slaves, which included laws that made it illegal to teach freedpeople to read and write and, in 1806, required newly freed slaves to leave the state.[296][297]

There is evidence that some of Washington's former slaves were able to buy land, support their families and prosper as free people. By 1812, Free Town in Truro Parish, the earliest known free African-American settlement in Fairfax County, contained seven households of former Washington slaves. By the mid 1800s, a son of Washington's carpenter Davy Jones and two grandsons of his postilion Joe Richardson had each bought land in Virginia. Francis Lee, younger brother of William, was well known and respected enough to have his obituary printed in the Alexandria Gazette on his death at Mount Vernon in 1821. Sambo Anderson – who hunted game, as he had while Washington's slave, and prospered for a while by selling it to the most respectable families in Alexandria – was similarly noted by the Úřední list when he died near Mount Vernon in 1845.[298] Research published in 2019 has concluded that Hercules worked as a cook in New York, where he died on May 15, 1812.[299]

A decade after Washington's death, the Pennsylvanian jurist Richard Peters wrote that Washington's servants "were devoted to him; and especially those more immediately about his person. The survivors of them still venerate and adore his memory." In his old age, Anderson said he was "a much happier man when he was a slave than he had ever been since", because he then "had a good kind master to look after all my wants, but now I have no one to care for me".[300] When Judge was interviewed in the 1840s, she expressed considerable bitterness, not at the way she he had been treated as a slave, but at the fact that she had been enslaved. When asked, having experienced the hardships of being a freewoman and having outlived both husband and children, whether she regretted her escape, she replied, "No, I am free, and have, I trust, been made a child of God by [that] means."[301]

Politické dědictví

Washington's will was both private testament and public statement on the institution.[278][220] It was published widely – in newspapers nationwide, as a pamphlet which, in 1800 alone, extended to thirteen separate editions, and included in other works – and became part of the nationalist narrative.[302] In the eulogies of the antislavery faction, the inconvenient fact of Washington's slaveholding was downplayed in favor of his final act of emancipation. Washington "disdained to hold his fellow-creatures in abject domestic servitude," wrote the Massachusetts Federalist Timothy Bigelow before calling on "fellow-citizens in the South" to emulate Washington's example. In this narrative, Washington was a proto-abolitionist who, having added the freedom of his slaves to the freedom from British slavery he had won for the nation, would be mobilized to serve the antislavery cause.[303]

An alternative narrative more in line with proslavery sentiments embraced rather than excised Washington's ownership of slaves. Washington was cast as a paternal figure, the benevolent father not only of his country but also of a family of slaves bound to him by affection rather than coercion.[304] In this narrative, slaves idolized Washington and wept at his deathbed, and in an 1807 biography, Aaron Bancroft wrote, "In domestick [sic ] and private life, he blended the authority of the master with the care and kindness of the guardian and friend."[305] The competing narratives allowed both Severní a Jižní to claim Washington as the father of their countries during the americká občanská válka that ended slavery more than half a century after his death.[306]

There is tension between Washington's stance on slavery, and his broader historical role as a proponent of liberty. He was a slaveholder who led a war for liberty, and then led the establishment of a national government that secured liberty for many of its citizens, and historians have considered this a paradox.[132] Historik Edmund Sears Morgan explained that Washington was not alone in this regard: "Virginia produced the most eloquent spokesmen for freedom and equality in the entire United States: George Washington, James Madison, and, above all, Thomas Jefferson. They were all slaveholders and remained so throughout their lives."[307] Washington recognized this paradox, rejected the notion of black inferiority, and was somewhat more humane than other slaveowners, but failed to publicly become an active supporter of emancipation laws due to Washington's fears of disunion, the racism of many other Virginians, the problem of compensating owners, slaves' lack of education, and the unwillingness of Virginia’s leaders to seriously consider such a step.[267][266]

Pamětní

In 1929, a plaque was embedded in the ground at Mount Vernon less than 50 yards (45 m) from the crypt housing the remains of Washington and Martha, marking a plot neglected by both groundsmen and tourist guides where slaves had been buried in unmarked graves. The inscription read, "In memory of the many faithful colored servants of the Washington family, buried at Mount Vernon from 1760 to 1860. Their unidentified graves surround this spot." The site remained untended and ignored in the visitor literature until the Mount Vernon Ladies' Association erected a more prominent monument surrounded with plantings and inscribed, "In memory of the Afro Americans who served as slaves at Mount Vernon this monument marking their burial ground dedicated September 21, 1983." V roce 1985 radar pronikající na zem survey identified sixty-six possible burials. Na konci roku 2017 identifikoval archeologický projekt zahájený v roce 2014, aniž by došlo k narušení obsahu, šedesát tři pohřebních pozemků kromě sedmi pozemků známých před zahájením projektu.[308][309][310]

Poznámky

- ^ Washington sídlil na Mansion House Farm, kde se pro jeho stůl pěstovalo ovoce, zelenina a byliny, plus květiny a exotické rostliny. Ve stájích se chovali koně a mezci a tropické rostliny se pěstovaly ve skleníku. V dalších budovách v Mansion House Farm se uskutečňovaly obchody jako kovářství, tesařství, výroba sudů (coopering), výroba a konzervace potravin, spřádání, tkaní a výroba obuvi. Některé plodiny se pěstovaly na této farmě, ale hlavní zemědělská činnost byla prováděna na čtyřech odlehlých farmách v okruhu mezi 2,4 km a 4,8 km od zámku: Dogue Run Farm, Muddy Hole Farm, Union Farm (vytvořený z dřívější Ferry Farm a French's Farm) a River Farm.[10] Vedoucí farmy odpovědný za chod statku se hlásil přímo do Washingtonu, zatímco na každé farmě byl zaměstnán dozorce.[11]

- ^ Šest z zotročených ve sčítání lidu z roku 1786 bylo uvedeno jako mrtvé nebo nezpůsobilé[20]

- ^ Mezi potomky svobodníka je ústní tradice West Ford že byl synem Washingtonu a Venuše, zotročené ženy patřící Washingtonovu bratrovi John Augustine Washington. Případ historika Henryho Wienceka je podle historika Philipa Morgana „tak nepřímý, aby byl fantazijní“, a neexistují žádné důkazy o tom, že by se Washington někdy setkal s Venuší, natož aby jí zplodil dítě.[85][86]

- ^ V rozhovoru z roku 1833 Washingtonův synovec Lawrence Lewis Souvisí s rozhovorem s jedním z washingtonských tesařů, který nahlásil incident, kde po chybě dostal „takovou facku po hlavě, že jsem se otočil dokola jako vršek“. Pokud komorník nedokázal správně vyčistit boty Washingtonu připravené na ráno, "sluha je dostal kolem hlavy, ale bez Genl. Zradil jakékoli vzrušení nad rámec úsilí okamžiku - za minutu poté nebyl o nic méně klidný a sebraný než obvykle . “[114]

- ^ Henriques je emeritním profesorem historie na Univerzitě George Masona a členem výboru Mount Vernon ve složení George Washington Scholars.[124]

- ^ Jižní karolínští vůdci byli pobouřeni, když Kongres přijal rezoluce, což Wiencek navrhuje jako první proklamaci emancipace, podporující tento návrh a hrozící odstoupením z války, pokud bude uzákoněna. Washington věděl, že tento program narazí na výrazný odpor v Jižní Karolíně, a nebyl překvapen, když nakonec selhal.[138][139] Wiencek pojednává o možnosti, že by se Washingtonova obava z nespokojenosti otroků po náboru jihokarolínských otroků rozšířila i na jeho vlastní otroky, a proto „odolával náborovému plánu, který by mohl vést ke ztrátě jeho majetku, a to navzdory naléhavé vojenské nutnosti“.[140]

- ^ Philip Morgan identifikuje čtyři body obratu: přechod od tabáku k obilninám v 60. letech 17. století a realizace ekonomické neefektivity instituce;[118] rozšíření washingtonských obzorů během americké revoluce a zásady, na nichž se bojovalo;[161] vliv abolicionistů, jako jsou Lafayette, Coke, Asbury a Pleasants v polovině 80. let 20. století, a podpora Washingtonu pro zrušení postupným legislativním procesem;[162] a pokusy Washingtonu oddělit se od otroctví v polovině 90. let 20. století.[163]

- ^ Ve své obecné historii historici Joseph Ellis a John E. Ferling za další faktor lze považovat zkušenost Washingtonu s viděním Afroameričanů bojujících za věc.[168][169]

- ^ Plochy otroctví byl jeden svazek ze souboru třiceti šesti, který Washington svázal pravděpodobně někdy po roce 1795. Svazky pokrývaly předměty, které pro něj měly obecně význam, jako zemědělství, revoluce, Společnost v Cincinnati a politika. Jediný pamflet šesti let z roku 1788 Plochy otroctví byl Vážný projev vládcům Ameriky, o nekonzistentnosti jejich chování při respektování otroctví, vydaná v roce 1783. Jednalo se o první pamflet ve svazku a Washington na svůj obálku napsal svůj podpis, stejně jako to učinil u prvního pamfletu v každém ze třiceti šesti svazků. Z jedenácti brožur o otroctví, které pravděpodobně nebyly považovány za závazné, bylo osm vydáno před rokem 1788. Jeden z nich, publikovaný v roce 1785, nebyl nikdy přečten. Z toho vyplývá, že Washington se o toto téma začal více zajímat počátkem 90. let 20. století.[171]

- ^ Ti dva diskutovali o otroctví, když Lafayette navštívil Washington v Mount Vernon v srpnu 1784, ačkoli Washington si myslel, že ještě není zralý čas na řešení, a ptali se, jak by mohla být plantáž ve Virginii provozována bez otrocké práce. Po návratu do Francie koupila Lafayette současnou plantáž ve francouzské kolonii Cayenne Francouzská Guyana, a poradil Washingtonu o jeho postupu dopisem v roce 1786. Lafayette vzal v úvahu obavy z náhlé emancipace otroků, platil a vzdělával otroky, které usadil na plantáži, než je osvobodil. Stal se vůdčí osobností francouzského hnutí proti obchodu s otroky a příslušným členem britského hnutí. Washington by o Lafayetteových protiotrokářských aktivitách v Cayenne nebo v Evropě nevěděl ani sám Lafayette; ačkoli ti dva pokračovali v korespondenci po zbytek života Washingtonu, téma otroctví z jejich dopisů prakticky zmizelo. Experiment v Cayenne skončil v roce 1792, kdy plantáž byla prodána francouzskou revoluční vládou po Lafayetteově uvěznění Rakušany.[179][180]

- ^ John Rhodehamel, bývalý archivář na Mount Vernon a kurátor amerických historických rukopisů na Huntingtonova knihovna,[189] charakterizuje Washington jako někoho, kdo si přál „především ten druh slávy, který znamenal trvalou pověst čestného muže“.[190] Podle Gordon S. Wood „Mnoho akcí [Washingtonu] po roce 1783 lze chápat pouze z hlediska této hluboké obavy o jeho pověst ctnostného vůdce.“[191] Ron Chernow píše: „... myšlenka na jeho vysoce určenou mezeru v historii nikdy nebyla [mysli Washingtonu] daleko.“[192]

- ^ Zdroje jsou v rozporu s jednáním Washingtonu o přijetí otroků od Mercera k vyrovnání dluhu. Kenneth Morgan uvádí, že Washington koupil otroky,[200] stejně jako Twohig, i když hlásí pět otroků.[19] Philip Morgan uvádí, že jednání s Mercerem propadla,[201] stejně jako Hirschfeld.[202] Peter Henriques uvádí, že Washington koupil zedníka v roce 1787, ale Kenneth Morgan, Twohig a Hirschfeld uvádějí pouze jednání o koupi jednoho, aniž by potvrdili, že ano.[203]

- ^ Humphreys byl bývalý poradce ve Washingtonu a začal osmnáctiměsíční pobyt na Mount Vernon v roce 1787, aby pomohl Washingtonu s jeho korespondencí a napsáním jeho životopisu.[215]