Paříž pod Napoleonem - Paris under Napoleon

Část série na |

|---|

| Historie Paříž |

|

| Viz také |

První konzul Napoleon Bonaparte se 19. února 1800 přestěhoval do Tuilerijského paláce a okamžitě po letech nejistoty a teroru revoluce začal znovu nastolovat klid a pořádek. Uzavřel mír s katolickou církví; mše se konaly znovu v Katedrála Notre Dame, kněží směli znovu nosit církevní oděvy a kostely zvonit.[1] Aby obnovil pořádek ve vzpurném městě, zrušil zvolenou pozici starosty Paříže a nahradil ji prefektem Seiny a policejním prefektem, které oba jmenovali. Každý z dvanácti okrsků měl svého vlastního starostu, ale jejich moc byla omezena na prosazování dekretů napoleonských ministrů.[2]

Poté, co se korunoval na císaře 2. prosince 1804 zahájil Napoleon sérii projektů, díky nimž se z Paříže stal císařský kapitál, který by soupeřil se starověkým Římem. Postavil pomníky francouzské vojenské slávy, včetně Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, sloupec v Umístěte Vendôme a budoucí kostel sv Madeleine, zamýšlený jako chrám vojenských hrdinů; a začal Arc de Triomphe. Aby zlepšil pohyb dopravy v centru Paříže, postavil novou novou ulici, Rue de Rivoli, od Place de la Concorde do Place des Pyramides. Učinil důležitá vylepšení městských kanalizací a zásobování vodou, včetně kanálu z Ourcq River a výstavba tuctu nových fontán, včetně Fontaine du Palmier na Place du Châtelet; a tři nové mosty; the Pont d'Iéna, Pont d'Austerlitz, včetně Pont des Arts (1804), první železný most v Paříži. The Louvre stal se Napoleonovým muzeem v křídle bývalého paláce a vystavoval mnoho uměleckých děl, která si přivezl ze svých vojenských tažení v Itálii, Rakousku, Holandsku a Španělsku; a militarizoval a reorganizoval Grandes écoles, proškolit inženýry a administrátory.

Mezi lety 1801 a 1811 počet obyvatel Paříže vzrostl z 546 856 na 622 636, což je téměř počet obyvatel před francouzskou revolucí, a do roku 1817 dosáhl 713 966. Za jeho vlády Paříž trpěla válkou a blokádou, ale udržela si pozici evropského hlavního města módy, umění, vědy, vzdělávání a obchodu. Po jeho pádu v roce 1814 bylo město obsazeno pruskou, anglickou a německou armádou. Byly obnoveny symboly monarchie, ale většina Napoleonových památek a některé z jeho nových institucí, včetně formy městské správy, hasičů a modernizovaných Grandes écoles, přežil.

Pařížané

Podle sčítání lidu provedeného vládou činila populace Paříže v roce 1801 546 856 osob. Do roku 1811 vzrostla na 622 636 osob.[3]

Nejbohatší Pařížané žili v západních čtvrtích města, podél Champs-Élysées a v okolí náměstí Place Vendome. Nejchudší Pařížané byli soustředěni na východě, ve dvou čtvrtích; kolem Mount Sainte-Genevieve v moderním 7. okrsku a ve faubourgu Saint-Marcel a faubourg Saint-Antoine. [4]

Počet obyvatel města se lišil podle sezóny; mezi březnem a listopadem 30-40 000 pracovníků do Paříže z francouzských regionů; kameníci a řezači kamene, kteří přišli ze středního masivu a Normandie pracovat na stavbě budov, tkalci a barviči z Belgie a Flander, a nekvalifikovaní dělníci z alpských oblastí, kteří pracovali jako zametači a nosiči ulic. Během zimních měsíců se vrátili domů s tím, co si vydělali.[5]

Stará a nová aristokracie

Na vrcholu sociální struktury Paříže byla aristokracie, stará i nová. V roce 1788, před revolucí, měla stará šlechta v Paříži 15-17 000 osob, asi tři procenta populace. Ti, kteří během teroru unikli popravě, uprchli do zahraničí do Anglie, Německa, Španělska, Ruska a dokonce i do Spojených států. Většina se vrátila za vlády Napoleona a mnozí našli pozice v novém císařském dvoře a vládě. Stavěli nové domy, většinou v oblasti kolem Champs-Élysées. Připojila se k nim nová aristokracie vytvořená Napoleonem, skládající se z jeho generálů, ministrů a dvořanů, stejně jako bankéřů, průmyslníků a těch, kteří zajišťovali vojenské zásoby; celkem asi tři tisíce osob. Noví šlechtici často uzavírali spojenectví sňatkem se starými rodinami, které potřebovaly peníze. Jeden starý aristokrat, vévoda z Montmorency, to řekl maršálovi Jean-de-Dieu Soult, kterého Napoleon ustanovil vévodou: „Jste vévoda, ale nemáte předky!“ Soult odpověděl: „Je to pravda. Jsme předkové.“[6]

Nejbohatší a nejvýznamnější Pařížané během první říše koupili městské domy mezi Palais Royale a Etoile, zejména na rue du Faubourg Saint Honoré a Chausée d'Antin: Joseph Bonaparte, starší bratr císaře, žil na 31 rue de Faubourg Saint-Honoré, jeho sestra Pauline na čísle 39, maršál Louis-Alexandre Berthier u čísla 35, maršále Bon-Adrien Jeannot de Moncey v čísle 63 a maršál Joachim Murat v čísle 55, což je nyní Élysée Palace, sídlo prezidentů Francie. Juliette Récamier bydlel v čísle 9 Chausée D'Antin, generále Jean Victor Marie Moreau u čísla 20 a Kardinál Fesch, strýc Napoleona, u čísla 68. Ostatní významní lidé z první říše se usadili na levém břehu, ve faubourgu Saint-Germain. Eugène de Beauharnais, syn císařovny Josephine, žil na 78 rue de Lille, Lucien Bonaparte, mladší bratr císaře, na 14 rue Saint-Dominique a maršál Louis-Nicolas Davout na 57 a později 59 na stejné ulici.[7]

Bohatí a střední třída

Pod starou a novou aristokracií byla velká střední třída s asi 150 000 osobami, což představovalo asi čtvrtinu obyvatel města. Do nižší střední třídy patřili malí obchodníci, řemeslníci, kteří měli několik zaměstnanců, státní zaměstnanci a lidé v svobodných povoláních; lékaři, právníci a účetní. Nová vyšší střední třída zahrnovala Napoleonovy generály a vysoké úředníky, nejúspěšnější lékaře a právníky a novou třídu bohatých Pařížanů, kteří vydělávali peníze prodejem zásob armády, nákupem a následným prodejem znárodněného majetku, například kostelů; a spekulacemi na akciovém trhu. Zahrnoval také hrst jednotlivců, kteří založili první průmyslové podniky v Paříži: chemické továrny, textilní továrny a stroje na výrobu továren. Nově zbohatlíci, podobně jako aristokracie, měli tendenci žít na západě města, mezi Place Vendôme a Etoile, nebo na levém břehu řeky Faubourg Saint-Germain. [8]

Řemeslníci a dělníci

Asi 90 000 Pařížanů, mužů, žen a často dětí, se živilo jako manuální pracovníci. Podle průzkumu provedeného policejním prefektem z roku 1807 pracoval největší počet v obchodech s potravinami; bylo zde 2250 pekařů, 608 cukrářů, 1269 řezníků, 1566 restaurátorů, 16111 limonádářů a 11 832 potravinářů a mnoho dalších ve specializovanějších oborech. Dvacet čtyři tisíce pracovalo ve stavebnictví, jako zedníci, tesaři, instalatéři a další řemesla. Třicet tisíc pracovalo v obchodech s oděvy, včetně krejčích, ševců, holičů a kloboučníků; dalších dvanáct tisíc žen pracovalo jako švadleny a čistily oděvy. Dvanáct tisíc pracovalo v nábytkářských dílnách; jedenáct tisíc v hutním průmyslu. Padesát procent pracujících bylo mladších než osmnáct nebo více než čtyřicet; během říše byla velká část dělníků odvedena do armády.[9]

Řemeslníci a dělníci byli soustředěni ve východních čtvrtích. Faubourg Saint-Antoine zahrnoval novou sklárnu Reuilly a továrny na výrobu porcelánu, keramiku, tapety, pivovary a mnoho menších dílen vyrábějících nábytek, zámky a zámečnické práce. Další významnou průmyslovou čtvrtí byl faubourg Saint-Marcel na levém břehu podél břehů řeky Bievre, kde byly umístěny koželužny a barvírny. Mnoho řemeslníků v těchto čtvrtích mělo jen dva pokoje; přední dílna s oknem sloužila jako dílna, zatímco celá rodina žila v temnější zadní místnosti. Dělnické čtvrti byly hustě obydlené; zatímco ve čtvrtích Champs-Élysée bylo 27,5 osob na hektar, v roce 1801 žilo na hektaru ve čtvrti Arcis 1500 osob, což zahrnovalo náměstí Place de Grève, Châtelet a Saint-Jacques de la Boucherie a hustotu 1000 do 1 500 osob v okolí Les Halles, rue Saint-Denis a rue Saint-Martin. Asi šedesát až sedmdesát procent obyvatel faubourgů Saint-Antoine a Saint-Marcel se narodilo mimo Paříž, většinou ve francouzských provinciích. Většina pocházela ze severu, Pikardie, Champagne, údolí Loiry, Berri a Normandie. [7]

Sluhové

Služebníci v domácnosti, z nichž dvě třetiny tvořili ženy, tvořili asi patnáct až dvacet procent populace hlavního města. Před revolucí pracovali převážně pro šlechtu, jejíž rodiny měly někdy až třicet služebníků. Během říše byli častěji zaměstnáni novou šlechtou, nově bohatou a střední třídou. Rodiny z vyšší střední třídy měly často tři sluhy; rodiny řemeslníků a obchodníků obvykle jeden měli. Životní podmínky služebníků do značné míry závisely na osobnosti pána, ale nikdy to nebylo snadné. Napoleon zrušil trest smrti, který dříve mohl být dán sluhovi, který ukradl jeho pánovi, ale každý služebník, který byl dokonce podezřelý z krádeže, by nikdy nemohl získat jinou práci. Každý zaměstnanec, který otěhotněl, oženil se nebo ne, mohl být okamžitě propuštěn.[10]

Prostitutky

Prostituce nebyla legální, ale během říše byla velmi běžná. Prostitutkami byly často ženy, které pocházely z provincií hledajících práci, nebo ženy, které měly zaměstnání na částečný úvazek, ale nedokázaly přežít z nízkého platu. V roce 1810, kdy měla Paříž přibližně 600 000 obyvatel, odhadoval ministr policie Savary 8 000 až 9 000 žen maisons zavíránebo domy prostituce; 3000 až 4000, kteří pracovali z pronajatého pokoje; 4000, kteří pracovali venku, v parcích, na nádvořích nebo dokonce na hřbitovech; a 7 000 až 8 000 prostitutek, když došly peníze, kteří byli jinak zaměstnáni v šití, prodeji kytic květin nebo v jiných málo placených profesích. To představovalo celkem pět až osm procent ženské populace města. [11] Podle jednoho účtu z roku 1814 měli svou vlastní sociální hierarchii; the kurtizány nahoře, jehož klienty byli výhradně šlechtici nebo bohatí; pak třída složená z hereček, tanečníků a divadelníků; potom částečně úctyhodné prostitutky ze střední třídy, které někdy přijímaly klienty doma, často se souhlasem manžela; pak nezaměstnané nebo pracující ženy, které potřebovaly peníze, až na nejnižší úroveň, které byly nalezeny v nejhorších čtvrtích města, v Port du Blé, na ulici Purgée a na ulici Planche Mibray.[12]

Chudé

Podle Chabrol de Volvic, prefekta Seiny v letech 1812 až 1830, se počet žebráků v Paříži pohyboval od více než 110 000 v roce 1802 do asi 100 000 osob v roce 1812. Během kruté zimy roku 1803 poskytly charitativní kanceláře města pomoc více než 100 000 osobám.[13] Nejchudší Pařížané žili na Montagne Saint-Genevieve a na faubourgech Saint-Antoine a Saint-Marcel a v úzkých uličkách Île de la Cité, které byly obzvláště přeplněné. Claude Lachaise, ve svém Topographie médicale de Paris (1822), popsal „bizarní shromáždění budov špatně postavených, hroutících se, vlhkých a tmavých, v nichž každý obývá dvacet devět nebo třicet osob, z nichž největší počet jsou zedníci, železáři, nositelé vody a pouliční obchodníci. ... problémy zvyšují malá velikost pokojů, těsnost dveří a oken, rozmanitost rodin nebo domácností, kterých může v jednom domě dosáhnout deset, a příliv chudých, které přitahuje nízká úroveň ceny bydlení. “ [14]

Děti

V Paříži bylo během Říše mnohem více dětí a mladých lidí než v moderní době. V roce 1800 bylo čtyřicet procent Pařížanů mladších osmnácti let, ve srovnání s 18,7 procenty v roce 1994. V letech 1801 až 1820 manželství produkovalo průměrně 4,3 dětí, v porovnání s pouhými 0,64 dětmi v roce 1990. Ve věku před antikoncepcí byla velká také se narodil počet nechtěných dětí, většinou chudým nebo pracujícím ženám. Pět tisíc osmdesát pět dětí bylo dáno Hospice des infants trouvées v roce 1806 asi čtvrtina z celkového počtu dětí narozených ve městě. Mnoho novorozenců bylo prostě tajně uvrženo do Seiny. Úmrtnost v městských sirotčincích byla velmi vysoká; jedna třetina zemřela v prvním roce, další třetina v druhém roce. Zatímco děti střední a vyšší třídy chodily do školy, děti pracujících a chudých šly do práce, často ve věku deseti let, do rodinného podniku nebo dílny.[15]

Manželství, rozvod a homosexualita

Pařížané pod Napoleonem se vzali relativně staří; průměrný věk manželství mezi lety 1789 a 1803 se pohyboval mezi třiceti a třiceti jedna u mužů a mezi dvaceti pěti a dvaceti šesti u žen. Nesezdané páry žijící společně v konkubinát, zejména v dělnické třídě, byly také běžné. Tyto páry byly často stabilní a dlouhodobé; třetina žila společně více než šest let, dvacet dva procent více než devět let. Rozvod byl běžný během revoluce a konzulátu, kdy jedno z pěti manželství skončilo rozvodem. Napoleon byl obecně nepřátelský k rozvodům, ačkoli on sám se rozvedl s císařovnou Josephine. V roce 1804 klesla míra rozvodovosti na deset procent. Počet sňatků v posledních letech Impéria po katastrofálním tažení v Rusku velmi vzrostl, protože mnoho mladých mužů se oženilo, aby se pokusili vyhnout vojenské službě. Počet sňatků se zvýšil z 4 561 v roce 1812 na 6 585 v roce 1813, což je největší počet od roku 1796. [16]

Homosexualita byla katolickou církví odsouzena, ale pokud byla diskrétní, byla v Paříži tolerována. Napoleon neschválil homosexualitu, ale během konzulátu, když nebyl přítomen v Paříži na vojenských kampaních, dal dočasnou moc otevřeně homosexuálnímu Jean-Jacques-Régis de Cambacérès. Policie tomu věnovala malou pozornost, pokud to nebylo zjevné. Gay prostitutky se běžně vyskytovaly na Quai Saint-Nicolas, místě Marché Neuf a Champs-Élysées. Prefekt policie v roce 1807 uvedl, že homosexuálové byli běžní mezi restaurátory, limonadiéry, krejčími a výrobci paruky, „způsobem, který byl upřímný a jemný, i když byli zřídka věrní“. Tolerance homosexuality trvala až do roku 1817, během obnovy monarchie, kdy začala kampaň represí.[17]

Peníze, platy a životní náklady

Metrický systém byl zaveden v roce 1803, stejně jako frank v hodnotě sto stokrát a sou, v hodnotě pěti centimů. Zlatá napoleonská mince měla hodnotu 20 nebo 40 franků a vláda rovněž vydala stříbrné mince v hodnotě pěti, dvou a jednoho franku. Vláda neměla prostředky na shromáždění a předělání všech mincí bývalých režimů, takže zlatý Louis s vyobrazením krále v hodnotě 24 liber a ecu, počet stříbra v hodnotě tři šest liber, byly také legální měnou. V oběhu byly také mince všech států v říši, včetně mincí německých států, severní a střední Itálie, Nizozemska a rakouského Nizozemska (nyní Belgie).[18]

V roce 1807 mohl kvalifikovaný pracovník, jako je klenotník, voňavkář, krejčí nebo výrobce nábytku, vydělat 4–6 franků denně; pekař vydělal 8–12 franků týdně; kameník vydělal 2–4 franky denně; nekvalifikovaný dělník, jako je stavební dělník, vydělal 1,50 až 2,5 franku denně. Velká část práce byla sezónní; většina stavebních prací se zastavila během zimy. Platy žen byly nižší; pracovník v tabákové továrně vydělal jeden frank denně, zatímco ženy vyrábějící výšivky nebo švadleny vydělaly 50-60 centimů denně, vládní platy v roce 1800 byly stanoveny na stupnici 8000 franků ročně pro vedoucího oddělení ministerstva na 2500 franků ročně za posla.[19]

Fixní ceny zboží byly během první říše vzácné; téměř každý produkt nebo služba byla předmětem vyjednávání. Ceny chleba však stanovila vláda a cena bochníku čtyř liber se během říše pohybovala mezi padesáti a devadesáti centimaty. Kilogram hovězího masa, v závislosti na kvalitě, stál mezi 95 a 115 centimy; litr obyčejného vína z Maconu, mezi 68-71 centimy. Pár hedvábných punčoch pro ženu stál 10 franků, pár mužských kožených bot stálo 11 až 14 franků. Císařovy slavné klobouky zakoupené u výrobce klobouků Poupard stály každý šedesát franků. Koupel v lázeňském domě stála 1,25 franku, účes pro ženu 1,10 franku, konzultace s lékařem stála 3–4 franky. Cena pokoje pro dvě osoby ve třetím patře v sousední čtvrti Saint-Jacques s nízkými příjmy byla 36 franků ročně. Průměrné nájemné Pařížanů se skromným příjmem bylo asi 69 franků ročně; nejbohatší osmina Pařížanů platila nájemné přes 150 franků ročně; v roce 1805 zaplatil sochař Moitte s domácností sedmi osob roční nájem ve výši 1500 franků za byt s velkým salonem a ložnicí s výhledem na Seinu, dvěma dalšími ložnicemi, jídelnou, koupelnou, kuchyní a jeskyní ve Faubourg Saint - Znovu. [20]

Správa města

Během francouzská revoluce Paříž měla krátce demokraticky zvoleného starostu a první vládu Pařížská komuna. Tento systém nikdy opravdu nefungoval a byl potlačen Francouzský adresář, který eliminoval pozici starosty a rozdělil Paříž na dvanáct samostatných obcí, jejichž vedoucí byli vybráni národní vládou. Nový zákon ze dne 17. února 1800 systém upravil; Z Paříže se stala jediná komuna rozdělená do dvanácti okrsků, z nichž každý měl svého starostu, který si znovu vybral Napoleon a národní vláda. Byla také vytvořena rada odboru Seiny, která měla fungovat jako jakási městská rada, ale její členové byli také vybráni národními vůdci. Skutečnými vládci města byli prefekt Seiny, který měl kancelář v Hôtel de Ville, a policejní prefekt, jehož ředitelství bylo na ulici rue Jerusalem a quai des Orfèvres na Ile de la Cité. Tento systém s krátkým přerušením během Pařížská komuna v roce 1871 zůstal v platnosti až do roku 1977.[21]

Paříž byla rozdělena na dvanáct okrsků a čtyřicet osm čtvrtí, což odpovídalo sekcím vytvořeným během francouzské revoluce. Obvody byly podobné, ale ne totožné s dnešními prvními dvanácti okrsky; byly očíslovány odlišně, přičemž okrsky na pravém břehu byly očíslovány od jedné do šesti zleva doprava a okrsky na levém břehu očíslovány zleva doprava od sedmi do dvanácti. Takže první obvod pod Napoleonem je dnes z velké části 8. obvodem, 6. napoleonský obvod je moderním 1. obvodem, napoleonský 7. je moderním 3.; a napoleonské 12. je moderní 5. místo. Hranice Paříže v roce 1800 jsou zhruba hranicemi 12 moderních okrsků; hranice města sledují trasu moderní linky metra 2 (Nation-Port Dauphine), zastavující na Charles-de-Gaulle-Etoile, a trasy linky 6, z Etoile do Nation. [22]

Policie a zločin

Veřejný pořádek v Paříži byl nejvyšší prioritou Napoleona. Jeho prefekt policie řídil čtyřicet osm policejních komisařů, jednoho pro každou čtvrť, a dalších dvě stě policejních inspektorů v civilu. Nikdo z policie ve skutečnosti neměl uniformy; uniformovaná policie byla zřízena až v březnu 1829. Policii podporovala obecní stráž, s 2 154 strážci pěšky a 180 na koni. [23]

Jedním z hlavních problémů policie bylo pašování zboží, zejména vína, do města kolem Zeď Ferme générale, postavený kolem města v letech 1784 až 1791, kde měli obchodníci platit cla. Mnoho pašeráků používalo tunely pod zdí; v letech 1801 a 1802 bylo objeveno sedmnáct tunelů; jeden tunel mezi Chaillotem a Passym byl dlouhý tři sta metrů. Ve stejném období bylo v jednom tunelu zabaveno šedesát sudů vína. Mnoho taveren a guingety, se objevila těsně za zdmi, zejména ve vesnici Montmartre, kde byly nezdaněné nápoje mnohem levnější než ve městě. Městská správa nakonec dokázala pašeráky porazit tím, že celním agentům u bran dala vyšší platy, pravidelně je střídala a strhávala budovy poblíž zdí, ze kterých pašeráci operovali. [21]

Krádež byla dalším společným zájmem policie, která se zvyšovala nebo snižovala v závislosti na ekonomických podmínkách; v roce 1809 bylo zaznamenáno 1400 krádeží, v roce 1811 však 2727. Vraždy byly vzácné; třináct v roce 1801, 17 v roce 1808 a 28 v roce 1811. Nejsenzačnějším zločinem tohoto období byl spáchaný obchodníkem Trumeau, který otrávil svou nejstarší dceru, aby jí nemusel platit věno. Přes některé notoricky známé zločiny zahraniční cestující uváděli, že Paříž byla jedním z nejbezpečnějších velkých měst v Evropě; po návštěvě v letech 1806-07 napsal Němec Karl Berkheim „Podle těch, kteří znají Paříž, ještě dlouho před revolucí nebylo toto město nikdy tak klidné jako v tuto chvíli. Dá se chodit v naprosté bezpečnosti, kdykoli v noci v ulicích Paříže. “ [24]

Hasiči

Na začátku říše bylo 293 hasičů v Paříži nedostatečně placených, netrénovaných a špatně vybavených. Obvykle žili doma a měli druhé zaměstnání, obvykle jako ševci. Hlásili se jak prefektovi Seiny, tak prefektovi policie, což způsobilo byrokratické spory. Měli pouze dva žebříky, jeden vedený v Národní knihovně a druhý na tržnici Les Halles. Jejich nedostatky se projevily 1. července 1810, kdy vypukl požár na rakouském velvyslanectví v Chausée d'Antin během plesu k oslavě svatby Napoleona a Marie-Louise z Rakouska. Napoleon a Marie-Louise vyvázli bez zranění, ale manželka rakouského velvyslance a princezny de la Leyen byla zabita a tucet dalších hostů zemřelo později na jejich popáleniny. Samotný Napoleon napsal zprávu o události s tím, že se objevilo pouze šest hasičů a několik z nich bylo opilých. Napoleon vydal dekret dne 18. září 1811, který militarizoval hasiče na prapor sapeur-pompiers, se čtyřmi rotami po sto čtyřiceti dvou mužů, pod prefektem policie a ministerstvem vnitra. Hasiči byli povinni žít ve čtyřech kasárnách postavených pro ně po celém městě a mít ve městě strážní službu.[25]

Zdraví a nemoc

Systém zdravotní péče v Paříži byl během revoluce a konzulátu velmi napjatý, nemocnicím bylo věnováno malé financování nebo byla věnována malá pozornost. Revoluční vláda ve jménu rovnosti zrušila požadavek, aby lékaři měli licence, a umožnila komukoli léčit pacienty; v roce 1801 nový napoleonský prefekt Seiny uvedl, že ze sedmi set osob uvedených v oficiálním obchodním almanachu jako „lékaři“ měly pouze tři sta formální lékařské vzdělání. Nový zákon ze dne 9. března 1803 obnovil titul „doktor“ a požadavek, aby lékaři měli lékařské tituly. Nicméně léčba byla podle moderních standardů primitivní; anestezie, antiseptika a moderní hygienické postupy dosud neexistovaly; chirurgové operovali holýma rukama a měli normální pouliční šaty s vyhrnutými rukávy.[26]

Napoleon reorganizoval nemocniční systém a dal jedenáct městských nemocnic s celkem pěti tisíci lůžky pod správu prefekta Seiny. To byl začátek systému městské veřejné lékařské pomoci pro chudé. Druhá hlavní nemocnice, Val-de-Grace, byla pod vojenskou správou. Nový systém přijal nejslavnější lékaře té doby, včetně Jean-Nicolas Corvisart, Napoleonův osobní lékař, a Philippe-Jean Pelletan. Nemocnice ošetřily 26 000 pacientů v roce 1805 a 43 000 v roce 1812; úmrtnost pacientů se pohybovala mezi deseti a patnácti procenty: 4216 zemřelo v roce 1805 a 5634 v roce 1812. [27]

Vážná epidemie chřipka zasáhl město v zimě 1802–1803; její nejvýznamnější trpící byli císařovna Josephine a její dcera, Hortense de Beauharnais, matka Napoleona III., která obě přežila; zabilo to básníka Jean François de Saint-Lambert a spisovatelé Laharpe a Maréchal. Napoleon vytvořil Radu pro zdraví pod policejním prefektem, aby sledoval bezpečnost dodávek vody, potravinářských výrobků a dopady nových továren a dílen na životní prostředí. Výbor také provedl první systematické průzkumy zdravotního stavu v pařížských čtvrtích a poskytl první rozsáhlé očkování proti neštovicím. Napoleon také usiloval o zlepšení zdraví města tím, že postavil kanál zajišťující čerstvou vodu a stavěl stoky pod ulicemi, které postavil, ale jejich účinky byly omezené. Bohaté zásobování vodou, zdravotní standardy pro bydlení a efektivní kanalizace přišly až Napoleonem III a Druhou říší. [27]

Hřbitovy

Před Napoleonem měl každý farní kostel ve městě vlastní malý hřbitov. Z důvodů veřejného zdraví se Ludvík XIV. Rozhodl zavřít hřbitovy uvnitř města a přemístit pozůstatky za hranice města, ale pouze jeden, největší, nevinných poblíž Les Halles, byl skutečně uzavřen. Zbývající hřbitovy byly od revoluce a zavření kostelů zanedbávány a byly častým terčem lupičů hrobů, kteří prodávali mrtvoly lékařským fakultám. Frochet, pařížský prefekt, nařídil výstavbu tří velkých nových hřbitovů na severu, východě a jihu města. První z nich, na východ, měl svůj první pohřeb 21. května 1804. Stal se známým jako Pere Lachaise, pro zpovědníka Ludvíka XIV., jehož venkovský dům byl na místě. Na severu byl rozšířen stávající hřbitov Montmartre a nový hřbitov byl plánován na jih na Montparnasse, ale otevřel se až v roce 1824. Kosti ze starých hřbitovů v rámci městských hranic byly exhumovány a přesunuty do opuštěného podzemního kamene lomy na kopci Montsouris. V letech 1810-11 dostal nový web název Katakomby a byl otevřen pro veřejnost.[28]

Architektura a panoráma města

Ulice

V západních čtvrtích města, poblíž Champs Élysées, byly ulice, většinou postavené v 17. a 18. století, přiměřeně široké a rovné. Jen velmi málo z nich, včetně Chausée d'Antin a rue de l'Odéon, mělo chodníky, které byly poprvé zavedeny do Paříže v roce 1781. Pařížské ulice ve středu a na východ od města, až na několik výjimek, byly úzké, kroucení a omezené vysokými řadami domů, někdy vysokými šesti nebo sedmi příběhy, které blokovaly světlo. Neměli žádné chodníky a měli úzký kanál uprostřed, který sloužil jako kanalizace a odtok bouře. Chodci byli nuceni soutěžit s dopravou ve středu ulice. Ulice byly často pokryty hustým bahnem, které přilnulo k botám a oblečení. Bláto se mísilo s výkaly koní, kteří táhli vozy a kočáry. Zvláštní pařížská profese decrotteurse objevil; muži, kteří byli odborníky na škrábání bahna z bot. Když pršelo, podnikatelé položili prkna na bahno a nabádali chodce, aby přes ně přešli.[29]Napoleon se snažil zlepšit pohyb dopravy v srdci města vytvořením nových ulic; v roce 1802 postavil na zemi bývalých klášterů Nanebevzetí a Capucins rue du Mont-Thabor. V roce 1804 zbořil klášter Feuillants vedle Louvru, kde byl Ludvík XVI. Krátce zadržen, než byl uvězněn ve starém chrámu, a zahájil výstavbu nové široké ulice, Rue de Rivoli, která byla prodloužena z Place de la Concorde Pokud Place des Pyramides. Byla postavena v letech 1811 až 1835 a stala se nejdůležitější osou východ-západ podél pravého břehu. To bylo nakonec dokončeno až na rue Saint-Antoine jeho synovcem Napoleonem III v roce 1855. V roce 1806 postavil na zemi kláštera Capucins další širokou ulici s chodníky, pojmenovanou rue Napoleon, mezi Umístěte Vendôme a velké bulváry. Po jeho pádu byl přejmenován Rue de la Paix. V roce 1811 Napoleon otevřel rue de Castiglione, také na místě starého kláštera Feulliants, aby spojil rue de Rivoli s Place Vendome.[30]

Mosty

Aby se zlepšil pohyb dopravy, zboží a lidí ve městě, Napoleon postavil tři nové mosty, kromě šesti již existujících, a dva z nich pojmenoval po svých slavných vítězstvích. Postavil Pont des Arts (1802–04) první železný most ve městě spojující levý břeh s Louvrem, jehož křídlo přeměnil na uměleckou galerii, zvanou Palais des Arts nebo Musée Napoleon, které dalo mostu jeho jméno. Paluba mostu byla lemována citrusovými stromy v květináčích a stála jeden sou přejít. Dále na východ postavil Pont d'Austerlitz (1801-1807) spojující Jardin des Plantes a dílny na levém břehu s dělnickými čtvrtími Faubourg Saint-Antoine. To bylo nahrazeno jeho synovcem, Napoleonem III, v roce 1854. Na západě postavil Pont d'Iéna, (1808–14), který spojoval velké cvičiště École Militaire na levém břehu s kopcem Chaillot, kde měl v úmyslu postavit palác pro svého syna, římského krále. Nový most byl právě dokončen při pádu Impéria; nový režim nahradil orly Napoleona počátečním králem Ludvík XVIII.

Čísla ulic

Napoleon dal do pařížských ulic ještě jeden důležitý příspěvek. Číslování domů začalo v roce 1729, ale každá část města měla svůj vlastní systém a někdy se stejný počet vyskytoval několikrát na stejné ulici, čísla byla mimo pořadí, číslo 3 bylo možné najít poblíž čísla 10, a počty čísel nebyly jednotné. 5. února 1805 uložil dekret policejního prefekta Duflota společný systém číslování ulic celému městu; čísla byla spárována, sudá čísla vpravo a lichá čísla vlevo, a čísla začínající v nejbližším bodě k Seině a zvyšující se, když odcházeli od řeky. The new numbers were put up in the summer of 1805, and the system remains in place today. [31]

The Passages

The narrowness, crowds and mud on the Paris streets led to the creation of a new kind of commercial street, the covered passage, dry and well-lit, where Parisians be sheltered from the weather, stroll, look in the shop windows, and dine in cafes. The first such gallery was opened at the Palais-Royal in 1786, and became immediately popular. It was followed by the Passage Feydau (1790–91), Passage du Caire (1799), Passage des Panoramas (1800), Galerie Saint-Honoré (1807), Passage Delorme (between 188 rue de Rivoli and 177 rue Saint-Honoré, in 1808, and the galerie and passage Montesquieu (now rue Montesquieu) in 1811 and 1812. The Passage des Panoramas took its name from an exhibition organized on the site by the American inventor Robert Fulton. He came to Paris in 1796 to try to interest Napoleon and the Francouzský adresář in his inventions, the steamship, submarine and torpedo; while waiting for an answer he built an exhibit space with two rotundas and showed panoramic paintings of Paris, Toulon, Jerusalem, Rome and other cities. Napoleon, who had little interest in the navy, rejected Fulton's inventions, and Fulton went to London instead. In 1800 the covered shopping street opened in the same building, and became a popular success. [32]

Památky

In 1806, in imitation of Ancient Rome, Napoléon ordered the construction of a series of monuments dedicated to the military glory of France. The first and largest was the Arc de Triomphe, built at the edge of the city at the Barrière d'Étoile, and not finished before July 1836. He ordered the building of the smaller Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel (1806–1808), copied from the arch of Oblouk Septimia Severuse and Constantine in Rome, next to the Tuileries Palace. It was crowned with a team of bronze horses he took from the façade of Bazilika svatého Marka v Benátky. His soldiers celebrated his victories with grand parades around the Kolotoč. He also commissioned the building of the Sloup Vendôme (1806–10), copied from the Trajanův sloup in Rome, made of the iron of cannon captured from the Russians and Austrians in 1805. At the end of the Rue de la Concorde (given again its former name of Rue Royale on 27 April 1814), he took the foundations of an unfinished church, the Église de la Madeleine, which had been started in 1763, and transformed it into the Temple de la Gloire, a military shrine to display the statues of France’s most famous generals.[33]

The churches

Among the most dismal sights in Napoleonic Paris were the churches which had been closed and wrecked during and after the Revolution. All of the churches were confiscated and made into national property, and were put on sale beginning in 1791. Most of the churches were demolished not by the Revolutionaries, but by real estate speculators, who bought them, took out and sold the furnishings, and demolished the buildings for building materials and to create land for real estate speculation. Twenty-two churches and fifty-one convents were destroyed between 1790 and 1799, and another 12 churches and 22 convents between 1800 and 1814. Convents were particular targets, because they had large buildings and extensive gardens and lands which could be subdivided and sold. Poumies de La Siboutie, a French doctor from Périgord who visited Paris in 1810, wrote: "Everywhere there are the hideous imprints of the Revolution. These are the churches and convents half-ruined, dilapidated, abandoned. On their walls, as well as on a large number of public buildings, you can read: "National Property for Sale"."" The words could still be read on the facade of Notre Dame, which had been saved, in 1833. When Napoleon was crowned Emperor in Notre Dame Cathedral in 1804, the extensive damage to the building inside and outside was hidden by curtains.[34]

On July 15, 1801, Napoleon signed a Concordat with the Pope, which allowed the thirty-five surviving parish churches and two hundred chapels and other religious institutions of Paris to reopen. The 289 priests remaining in Paris were again allowed to wear their clerical costumes in the street, and the church bells of Paris (those which had not been melted down) rang again for the first time since the Revolution. However, the buildings and property which had been seized from the church was not returned, and the Parisian clergy were kept under the close supervision of the government; the bishop of Paris was nominated by the Emperor, and confirmed by the Pope.[35]

Voda

Prior to Napoleon, the drinking water of Paris came either from the Seine, from wells in the basements of buildings, or from fountains in public squares. Water bearers, mostly from the Auvergne, carrying two buckets on a pole over their shoulder, carried water from the fountains or, since there was a charge for water from fountains, or, if the fountains were too crowded, from the Seine, to homes, for a charge of a sou (five centimes) for a bucket of about fifteen liters. The fountains were supplied with water by two large pumps next to the river, the Samaritaine and Notre-Dame, dating from the 17th century. and by two large steam pumps installed in 1781 at Chaillot and Gros Caillou. In 1800 there were fifty-five fountains for drinking water in Paris, one per each ten thousand Parisians. The fountains only ran at certain hours, were turned off at night, and there was a small charge for each bucket taken.

Shortly after taking power, Napoleon told the celebrated chemist, Jean-Antoine Chaptal, who was then the Minister of the Interior: "I want to do something great and useful for Paris." Chaptal replied immediately, "Give it water". Napoleon seemed surprised, but the same evening ordered the first studies of a possible aqueduct from the Ourcq River to the basin of La Valette in Paris. The canal was begun in 1802, and completed in 1808. Beginning in 1812, the water was distributed free to Parisians from the city fountains. In May 1806 Napoleon issued a decree that water should run from the fountains both day and night. He also built new fountains around the city, both small and large, the most dramatic of which were Egytpian Fountain on rue de Sèvres and the Fontaine du Palmier, both still in existence.He also began construction of the Canal St. Martin to further river transportation within the city.[33][36]

Napoléon's last water project was, in 1810, the Elephant of the Bastille, a fountain in the shape of a colossal bronze elephant, twenty-four meters high, which was intended for the centre of the Place de la Bastille, but he did not have time to finish it: an enormous plaster mockup of the elephant stood in the square for many years after the emperor's final defeat and exile.

pouliční osvětlení

During the First Empire, Paris was far from being the City of Light. The main streets were dimly illuminated by 4,200 oil lanterns hung from posts, which could be lowered on a cord so they could be lit without a ladder. The number grew to 4,335 by 1807, but was still far from sufficient. One problem was the quantity and quality of the oil being supplied by private contractors; lamps did not burn all night, and often did not burn at all. Also, lamps were placed far apart, so much of the street remained in darkness. For this reason persons going home after the theater or who needed to travel through the city at night hired porte-falots, or torch-bearers, to illuminate their way. Napoleon was furious at the shortcoming: in May 1807, from his military headquarters in Poland, he wrote to Fouché, his Minister of Police, responsible for street lights: "I've learned that the streets of Paris are no longer being lit." (May 1); "The non-lighting of Paris is becoming a crime, it's necessary to put an end to this abuse, because the public is beginning to complain." (23 May). [37]

Přeprava

For most Parisians, the sole means of travel was on foot; the first omnibus did not arrive until 1827. For those with a small amount of money, it was possible to hire a kočár, a one-horse carriage with a driver which carried either two or four passengers. They were marked with numbers in yellow, had two lanterns at night, and were parked at designated places in the city. The kabriolet, a one-horse carriage with a single seat beside the driver, was quicker but offered little protection from the weather. Altogether there were about two thousand fiacres and cabriolets in Paris during the Empire. The fare was fixed at one franc for a journey, or one franc twenty-five centimes for an hour, and one franc fifty for each hour after that. As the traveler Pierre Jouhaud wrote in 1809: "Independent of the fixed price, one usually gave a small gratuity which the drivers regarded as their proper tribute; and one could not refuse to give it without hearing the driver vomit a torrent of insults. "[38] Wealthier Parisians owned carriages, and well-off foreigners could hire them by the day or month; in 1804 an English visitor hired a carriage and driver for a week for ten Napoleons, or two hundred francs. In all, the narrow streets of Paris were filled with about four thousand private carriages, a thousand carriages for rent, about two thousand fiacres and cabriolets, in addition to thousands of carts and wagons delivering merchandise. There were no police directing traffic, no stop signs, no uniform system of driving on the right or left, no traffic rules, and no sidewalks, which meant both vehicles and pedestrians filled the streets. [39]

Volný čas

Svátky a festivaly

The calendar of Paris under Napoleon was full of holidays and festivals. The first great celebration was devoted to the coronation of the Emperor on 2 December 1804, which was preceded by a procession including Napoleon, Josephine and the Pope through the streets from the Tuileries to the Cathedral of Notre Dame, and followed on December 3 by public dances, tables of food, four fountains filled with wine at the Marché des Innocents, and a lottery giving away thousands of packages of food and wine. . The military victories of the Emperor were given special celebrations with volleys of cannons and military reviews; the victory at the Bitva u Slavkova was celebrated on 22 December 1805; z Bitva u Jeny – Auerstedt on 14 October 1805.[40]

The 14th of July 1800. the anniversary of the storming of the Bastille, a solemn holiday after the Revolution, was transformed into the Festival of Concord and Reconciliation, and into a celebration of the Emperor's victory at the Bitva o Marengo one month earlier. Its main feature was a grand military parade from the Place de la Concorde to the Champs de Mars, and the laying of the first stone of the foundation of a column dedicated to the armies of the Republic, later raised on Place Vendôme. Napoleon, a champion of order, was not comfortable with a holiday which celebrated a violent revolution. The old battle songs of the Revolution, the Marseillaise a Chant du Depart were not played at the celebration; they were replaced by Hymne a l'Amour podle Gluck. From 1801 to 1804, the 14th of July remained a holiday, but was barely celebrated. In 1805, it ceased to be a holiday, and was not celebrated again until 1880.[40] Another major celebration took place on 2 April 1810 to mark the marriage of Napoleon with his new Empress, Marie-Louise of Austria. Napoleon himself organized the details of the event, which he believed marked his acceptance by the royal families of Europe. It included the first illumination of the monuments and bridges of Paris, as well as arches of triumph and a spectacle on the Champs-Élysée, called "The Union of Mars and Flore"", with 580 costumed actors.[40]

Besides the official holidays, Parisians again celebrated the full range of religious holidays, which had been abolished during the Revolution. Oslava Karneval, and masked balls, which had been forbidden during the Revolution, resumed, though under careful police supervision. On Mardi Gras thousands of Parisians in masks and costumes filled the streets, on foot, horseback and in carriages. The 15th of August became a new holiday, the Festival of Saint-Napoleon. It marked the birthday of the Emperor, the Catholic festival of the Assumption, and the anniversary of the Concordat, signed by Napoleon and the Pope on that day in 1801, which allowed the churches of France to reopen. In 1806 the Pope was persuaded to make it an official religious holiday, but its celebration ended with the downfall of the Emperor.[40]

The Palais-Royal

It was almost impossible to walk in the narrow streets of Paris, due to the mud and traffic, and the Champs-Élysées did not yet exist, so upper and middle class Parisians took their promenades on the grand boulevards, in the public and private parks and gardens, and above all in the Palais-Royal. The arcades of the Palais-Royal, as described by the German traveler Berkheim in 1807, contained boutiques with glass show windows displaying jewelry, fabrics, hats, perfumes, boots, dresses, paintings, porcelain, watches, toys, lingerie, and every type of luxury goods. In addition there were offices of doctors, dentists and opticians, bookstores, offices for changing money, and salons for dancing, playing billiards and cards. There were fifteen restaurants and twenty-nine cafes, plus stalls which offered fresh waffles from the oven, sweets, cider and beer. The galleries also offered gambling salons and expensive houses of prostitution. The gallery was busy from the early morning, when people came to read the newspapers and do business, and became especially crowded between five and eight in the evening. At eleven, when the shops closed and the theaters finished, a new crowd arrived, along with several hundred prostitutes, seeking clients. The gates were closed at midnight.[41]

Velké bulváry

Next to the Palais-Royal, the most popular places for promenades were the Grands Boulevards, which had, after the Palais-Royal, the greatest concentration of restaurants, theaters, cafes, dance halls, and luxury shops. They were the widest streets in the city, about thirty meters broad, lined with trees and with space for walking and for riding horses, and stretched from la Madeleine to the Bastille. The most crowded part was the Boulevard des Italiens and Boulevard du Temple, where the restaurants and theaters were concentrated. [42] The German traveler Berkheim gave a description of the boulevards as they were in 1807; "It is especially from noon until four or five in the afternoon that the boulevards are the busiest. The elegant people of both sexes promenade there then, showing off their charms and their boredom.".[43] The most best-known landmarks on the boulevards were the Café Hardi, at rue Cerutti, where businessmen gathered, the Café Chinois and Pavillon d'Hannover, a restaurant and bath house in the form of a Chinese temple; and Frascati's at the corner of rue Richelieu and boulevard Montmartre, famous for its ice creams, elegant furnishings and its garden, where in summer, according to Berkheim, gathered "the most elegant and beautiful women of Paris." However, as Berkheim observed, "As everything in Paris is about fashion and fantasy, and since everything that is pleasing at this moment must be, for the same reason, considered fifteen days later to be dull and boring," and therefore once the more šik gardens of Tivoli opened, the fashionable Parisians largely abandoned Frascati for a time and went there. In addition to the theaters, panoramas (see below) and cafes, the sidewalks of the boulevards offered a variety of street theater; puppet shows, dogs dancing to music, and magicians performing.[43]

Pleasure Gardens and Parks

Pleasure gardens were a popular form of entertainment for the middle and upper classes, where, for an admission charge of twenty sous, visitors could sample ice creams, see pantomimes, acrobatics and jugglers, listen to music, dance, or watch fireworks. The most famous was Tivoli, which opened in 1806 between 66 and 106 on rue Saint-Lazare, where the entrance charge was twenty sous. The Tivoli orchestra helped introduce the waltz, a new dance imported from Germany, to the Parisians. The city had three public parks, the Tuilerijská zahrada, Lucemburská zahrada a Jardin des Plantes, all of which were popular with promenaders.[44]

The theater and opera

The theater was a highly popular form of entertainment for almost all classes of Parisians during the First Empire; there were twenty-one major theaters active, and more smaller stages. At the top of the hierarchy of theaters was the Théâtre Français (today the Comédie-Française ), at the Palais-Royal. Only classic French plays were performed there. Tickets ranged in price from 6.60 francs in the first row of boxes down to 1.80 francs for a seat in the upper gallery. Evening dress was required for the premieres of plays. At the other end of the Palais-Royal the Théâtre Montansier, which specialized in vaudeville and comedy. The most expensive ticket there was three francs, and audiences were treated with a program of six different farces and theater pieces. Another highly popular stage was the Théâtre des Variétés on Boulevard Montmartre. on owners of theater regularly invited fifty well-known Paris courtesans to the opening nights, to increase the glamour of the events; the courtesans moved from box to box between acts, meeting their friends and clients.[45]

Napoleon often attended the classical theater, but was disdainful and suspicious of popular theater; he did not permit any opposition or ridicule of the army or of himself. Imperial censors reviewed the scripts of all plays, and on 29 July 1807, he issued a royal decree which reduced the number of theaters from twenty-one to nine. [46]

The Paris Opera at the time performed in the former theater of Montansier on rue Richelieu, facing the National Library. It was the largest hall in the city, with one thousand seven hundred seats. The aisles and corridors were narrow, the air circulation was minimal, it was badly-lit and had poor visibility, but it was nearly always full. It was not only the rich who attended the opera; seats were available for as little as fifty centimes. Napoleon, as a Corsican, he had a strong preference for Italian opera, and he was suspicious of any other kind. In 1805, he wrote from his army camp at Boulogne to Fouché, his chief of police, "What is this piece called Don Juan which they want to perform at the Opera?" When he attended a performance, the orchestra played a special fanfare for his entry and his departure. The Opera was also noted for its masked balls, which attracted a large and enthusiastic public. [46]

Panoramata

Panoramas, or large-scale paintings mounted in a circular room to give a 360-degree view of a city or an historic event, were very popular in Paris at the beginning of the Empire. The American inventor, Robert Fulton, who was in Paris to try to sell his inventions, the steamboat, a submarine and a torpedo, to Napoleon, bought the patent in 1799 from the inventor of the panorama, the English artist Robert Barker, and opened the first panorama in Paris in July 1799; bylo to Vue de Paris by the painters Constant Bourgeois, Denis Fontaine and Pierre Prévost. Prévost went on to make a career of painting panoramas, making eighteen before his death in 1823.[47] Three rotundas were built on boulevard Montmartre between 1801 and 1804 to show panoramic paintings of Rome, Jerusalem, and other cities. They gave their name to the Passage des Panoramas, where they were located [48]

The Guinguettes

While the upper and middle class went to the pleasure garden, the working class went to the guinguette. These were cafes and cabarets located just outside the city limits and customs barriers, open on Sundays and holidays, where wine was untaxed and cheaper, and there were three or four musicians playing for dancing. They were most numerous in the villages of Belleville, Montmartre, Vaugirard and Montrouge.[49]

Móda

Ženy

Women's fashion during the Empire was set to a large degree by the Empress Joséphine de Beauharnais and her favorite designer, Hippolyte Leroy, who was inspired by the Roman statues of the Louvre and the frescoes of Pompeii. Fashions were also guided by a new magazine, the Journal des Dames et des Modes, with illustrations by the leading artists of the day. The antique Roman style, introduced during the Revolution, continued to be popular but was modified because Napoleon disliked immodesty in women's clothing; low necklines and bare arms were banned. The waist of the Empire gowns was very high, almost under the arms, with a long pleated skirt down to the feet. Corsets were abandoned, and the preferred fabric was mousseline. The main fashion accessory for women was the shawl, inspired by the Orient, made of cashmere or silk, covering the arms and shoulders. Napoleon's military campaigns also influenced fashion; after the Egyptian campaign, women began to wear turbans; after the Spanish campaign, tunics with high shoulders; and after the campaigns in Prussia and Poland, Polish furs and a long coat called a pelisse. They also wore jackets inspired by military uniforms, with epaulettes. In cold weather women wore a redingote, from the English word "riding coat", borrowed from men's fashion, or, after 1808, a witchoura, a fur coat with a hood.[50]

More than anyone else, the Empress Josephine set the fashion style of the Empire (1807)

Juliette Récamier tím, že François Gérard (1807)

Madame Riviere, by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1805)

Parisian fashions (1810)

Portrait of Eleanore de Montmorency. (1810) The turban became popular after Napoleon's Egyptian campaign.

Muži

During the Revolution, the culotte, or short trousers with silk stockings, and the extravagance fashions, lace and bright colors of the nobility had disappeared, and were replaced by trousers and greater simplicity. The purpose of men's fashion was to show one's wealth and social position; colors were dark and sober. Under the Empire, the culotte returned, worn by Napoleon and his nobles and the wealthy, but trousers were also worn. Men's fashion was strongly influenced by the French aristocrats who returned from exile in England; they introduced English styles, including the large overcoat they called the carsick, going down to the feet; the jacket with a collar going up to the ears; a white silk necktie wrapped around the neck; an English high hat with a broad brim, and high boots. In the late Empire, men's fashion tried for a more military look, with a narrow waist and a chest expanded by several layers of vests. [51]

Portrait of a gentleman by Léopold Boilly, about 1800.

Spisovatel Chateaubriand v roce 1808.

A Parisian gentleman, painted by Ingres (1810).

Každodenní život

Jídlo a pití

The staple of the Parisian diet was bread; unlike rural France, where peasants ate dark bread, baked weekly, Parisians preferred a spongy white bread with a firm crust, fresh from the oven, which they commonly ate by soaking it in a meat bouillon. It was similar to the modern baguette, not invented until the 20th century, but took longer to make. Parisians ate an average of 500 grams of bread, or two loaves a day; laborers consumed four loaves a day. Napoleon wanted to avoid the popular uprisings of 1789 caused by bread shortages, so the price of bread was strictly controlled between 1800 and 1814, and was much lower than outside the city. Parisians were very attached to their variety of bread; in times of grain shortages, when the government attempted to substitute cheaper dark breads, the Parisians refused to buy them.[52]

Meat was the other main staple of the diet, mostly beef, mutton and pork. There were 580 butchers registered in Paris in 1801, and prices of meat, like bread, were strictly regulated. Fish was another important part of the Parisian diet, particularly fresh fish from the Atlantic, brought to the city from the ports on the coast. Consumption of fresh fish grew during the First Empire, amounting to 55 percent of fish consumption, and it gradually replaced the salted fish which had previously been an important part of the diet, but which were harder to obtain due to the long war at sea between England and France. Seafood accounted for only about ten percent of what Parisians spent on meat; and was slightly less than what they spent on poultry and game.[52]

Cheeses and eggs were only a small part of the Parisian diet, since there was no adequate refrigeration and no rapid way to deliver them to the city. The most common cheeses were those of the nearest region, brie, and then those from Normandy. Fresh fruits and vegetables from the Paris region, potatoes, and dried vegetables, such as lentils and white beans, completed the diet. [52]

Wine was a basic part of the Parisian diet, ranking with bread and meat. Fine wines arrived from Bordeaux, ordinary wines were brought to the city in large casks from Burgundy and Provence; lesser quality wines came from vineyards just outside the city, in Montmartre and Belleville. Beer consumption was small, was only eight percent of that of wine, and cider only three percent. The most common strong alcoholic beverage was eau-de-vie, with as much as twenty-seven percent alcohol. It was most popular among the working class Parisians.[53]

Coffee had been introduced to Paris in about 1660, and came from Martinik and the IÎe de Bourbon, now Shledání. The English blockade of French ports cut off the supply, and Parisians were forced to drink substitutes made from the čekanka nebo žaludy. The blockade also cut off the supplies of chocolate, tea and sugar. Napoleon encouraged the growing of sugar beets to replace cane sugar, and in February 1812 he went himself to taste the products of the first sugar beet refineries opened just outside the city, at Passy and Chaillot.[53]

Cafés and restaurants

There were more than four thousand cafés in Paris in 1807, but due to the English naval blockade they were rarely able to obtain coffee, sugar, or rum, their main staples. Many of them were transformed into ledovce, which served ice cream and sorbet. One of the most prominent was the Café de Paris, located next to the statue of Henry IV on the Pont Neuf, facing Place Dauphine. The other well-known cafés were clustered in the galleries of the Palais Royal; these included the Café de Foix, the Café de Chartres, the Café de la Rotonde, which had a pavilion in the garden; the Café Corazza, where one could find newspapers from around Europe; and the Café des Mille Colonnes. The German traveler Berkheim described Café Foix: "this café, which normally brings together only high society, is always full, especially after the performances of the Théâtre français and the Montansier. They take their ice creams and sorbets there; and very rarely does one find any women among them."[54]

In the cellars beneath the Palais Royal were several other cafés for a less aristocratic clientele, where one could eat a full meal for twenty-five centimes and enjoy a show; The Café Sauvage had dancers in exotic costumes from supposedly primitive countries; the Café des Aveugles had an orchestra of blind musicians; and the Café des Variétés had musicians in one grotto and vaudeville theater performances in another. Berkheim wrote: "The society is very mixed; composed ordinarily of petit bourgeois, workers, soldiers, servants, and women with large round bonnets and large skirts of wool... there is a continual movement of people coming and going." [54]

The first restaurants in the modern sense, with elaborate cuisine and service, had appeared in Paris just before the Revolution. By 1807, according to Berkheim, there were about two thousand restaurants in Paris in 1807, of all categories. Most of the highest-quality and most expensive restaurants were located in the Palais-Royal; these included Beauvilliers, Brigaud, Legacque, Léda, and Grignon. Others were on the boulevards de Temple or Italiens. The Rocher de Cancale, known for its oysters, was on rue Montorgueil near the markets of Les Halles, while Ledoyen was at the western edge of the city, on the Champs-Élysées.[55]

The menu of one restaurant, Véry, described by the German traveler August Kotzebue in 1804, gives an idea of the cuisine of the top restaurants; it began with a choice of nine kinds of soup, followed by seven kinds of pâté, or platters of oysters; then twenty-seven kinds of hors d'oeuvres, mostly cold, including sausages, marinated fish, or choucroute. The main course followed, a boiled meat with a choice of twenty sauces, or a choice of almost any possible variety of a beefsteak. After this was a choice of twenty-one entrées of poultry or wild birds, or twenty-one dishes of veal or mutton; then a choice of twenty-eight different fish dishes; then a choice of fourteen different roast birds; accompanied by a choice of different entremets, including asparagus, peas, truffles, mushrooms, crayfish or compotes. After this came a choice of thirty-one different desserts. The meal was accompanied by a choice made of twenty-two red wines and seventeen white wines; and afterwards came coffee and a selection of sixteen different liqueurs. [56]

The city had many more modest restaurants, where one could dine for 1.50 francs, without wine. Employees with small salaries could find many restaurants which served a soup and main course, with bread and a carafe of wine, for between fifteen and twenty-one francs a week, with two courses with bread and a carafe. For students in the Left Bank, there were restaurants like Flicoteau, on rue de la Parcheminerie, which had no tablecloths or napkins, where diners ate at long tables with benches, and the menu consisted of bowls of bouillon with pieces of meat. Diners usually brought their own bread, and paid five or six centimes for their meal.[57]

Náboženství

Just fifty days after seizing power, on 28 December 1799, Napoleon took measures to establish better relations with the Catholic Church in Paris. All the churches which had not yet beensold as national property or torn down, fourteen in number in January 1800, with four added during the year, were to be returned to religious use. Eighteen months later, with the signing of the Konkordát between Napoleon and the Pope, churches were allowed to hold mass, ring their bells, and priests could appear in their religious attire on the streets. After the Reign of Terror, priests were hard to find in Paris; of 600 priests who had taken the oath to the government in 1791, only 75 remained in 1800. Many had to be brought to the city from the provinces to bring the number up to 280. When the bishop of Paris died in 1808, Napoleon tried to appoint his uncle, Cardinal Fesch, to the position, but Pope Pious VII, in conflict with Napoleon over other matters, rejected him. Fesch withdrew his candidacy and another ally of Napoleon, Bishop Maury, took his place until Napoleon's downfall in 1814.

The number of Protestants in Paris under the Empire was very small; Napoleon accorded three churches for the Calvinists and one church for the Lutherans. The Jewish religious community was also very small, with 2733 members in 1808. They did not have a formal temple until 1822, after the Empire, with the inauguration of the synagogue on rue Notre-Dame-du-Nazareth. ,[58]

Vzdělávání

Schools, collèges and lycées

During Old Regime, the education of young Parisians until university age was done by the Catholic church. The Revolution destroyed the old system, but did not have time to create a new one. Lucien Bonaparte, the Minister of the Interior, went to work to create a new system. A bureau of public instruction for the prefecture of the Seine was established on 15 February 1804. Charity schools for poorer children were registered, and had a total of eight thousand students, and were mostly taught by Catholic brothers. An additional four hundred schools for middle class and wealthy Parisian students, numbering fourteen thousand, were registered. An 1802 law formalized a system of collèges and lycées for older children. The principal subjects taught were mathematics and Latin, with a smaller number of hours given to Greek, and one hour of French a week, history, and a half-hour of geography a week. Arithmetic, geometry and physics were the only sciences taught. Philosophy was added as a subject in 1809. About eighteen hundred students, mostly from the most wealthy and influential families, attended the four most famous lycées in Paris in 1809; the Imperial (now Louis le Grand); Charlemagne; Bonaparte (now Condorcet); and Napoléon (now Henry IV). These competed with a large number of private academies and schools.

The University and the Grandes Écoles

The University of Paris before the Revolution had been most famous as a school of theology, charged with enforcing religious orthodoxy; it was closed in 1792, and was not authorized to re-open until 1808, with five faculties; theology, law, medicine, mathematics, physics and letters. Napoleon made it clear what its purpose was, in a letter to the rectors in 1811; "the University does not have as its sole purpose to train orators and scientists; above all it owes to the Emperor the creation of faithful and devoted subjects.".[59] In the academic year 1814-15, it had a total of just 2500 students; 70 in letters, 55 in sciences, 600 in medicine, 275 in pharmacy, and 1500 in law. The law students were being trained to be magistrates, lawyers, notaries and other administrators of the Empire. A degree in law took three years, or four to earn a doctorate, and cost students about one thousand francs; a degree in theology required 110 francs, in letters or sciences, 250 francs. [59]

While he tolerated the University, the schools that Napoleon valued the most were the École Militaire, the military school, and the Grandes Écoles, which had been founded at the end of the old regime or during the Revolutionary period; the Conservatoire national des arts et métiers; the École des Ponts et Chausées, (Bridges and highways); the École des Mines de Paris (school of Mines), the École Polytechnique a École Normale Supérieure, which trained the engineers, officers, teachers, administrators and organizers he wanted for the Empire. He re-organized them, often militarized them, and gave them the highest prestige in the French educational system. [60]

Books and the press

Freedom of the press had been proclaimed at the beginning of the Revolution, but had quickly disappeared during the Vláda teroru, and was not restored by the succeeding governments or by Napoleon. In 1809, Napoleon told his Council of State: "The printing presses are an arsenal, and should not be put at the disposition of anyone...The right to publish is not a natural right; printing as a form of instruction is a public function, and therefore the State can prevent it."[61] Supervision of the press was the responsibility of the Ministry of the Police, which had separate bureaus to oversee newspapers, plays, publishers and printers, and bookstores. The Prefecture of Police had its own bureau which also kept an eye on printers, bookstores and newspapers. All books published had to be approved by the censors, and between 1800 and 1810 one-hundred sixty titles were banned and seized by the police. The number of bookstores in Paris dropped from 340 in 1789 to 302 in 1812; in 1811 the number of publishing houses was limited by law to no more than eighty, almost all in the neighborhood around the University.[62]

Censorship of newspapers and magazines was even stricter. in 1800 Napoleon closed down sixty political newspapers, leaving just thirteen. In February 1811 he decided that this was still too many, and reduced the number to just eight newspapers, almost supporting him. One relatively independent paper, the Journal de l'Empire continued to exist, and by 1812 was the most popular newspaper, with 32,000 subscriptions. Newspapers were also heavily taxed, and subscriptions were expensive; an annual subscription cost about 56 francs in 1814. Because of the high cost of newspapers, many Parisians went to cabinets litteraires or reading salons, which numbered about one hundred and fifty. For a subscription of about six francs a month, readers could find a selection of newspapers, plus billiards, cards or chess games. Some salons displayed caricatures of the leading figures of the day. [63]

Umění

Napoleon supported the arts, as long as the artists supported him. He gave substantial commissions to painters, sculptors and even poets to depict his family and the great moments of the Empire. The principal showcase for paintings was the Paris Salon, which had been started in 1667 and from 1725 took place in the Salon carré of the Louvre, from which it took its name. It was an annual event from 1795 until 1801, then was held every two years. It usually opened in September or October, and as the number of paintings grew, it occupied both the Salon carré a Apollónova galerie. V roce 1800 bylo vystaveno 651 obrazů; v roce 1812 bylo vystaveno 1353 obrazů. Hvězdami salonu byli malíři historie, Pierre-Narcisse Guérin, Antoine-Jean Gros, Jacques-Louis David, Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson a Pierre-Paul Prud'hon, kteří malovali velká plátna událostí Říše a hrdinů a hrdinek starověkého Říma. Salon byl jednou z hlavních společenských událostí roku a přilákal obrovské davy. Salon měl své vlastní politické citlivosti; Dne 22. října 1808 ředitel Louvru, Vivant Denon, skryl portrét spisovatele a filozofa François-René de Chateaubriand když císař navštívil Salon, protože Chateaubriand císaře kritizoval. Napoleon věděl, co se stalo, a požádal ho, aby to viděl. Rozvod Napoleona a Josephine v roce 1810 byl ještě citlivějším tématem; musela být odstraněna z obrazů v salonu, kde byla vylíčena. David ji odstranil ze své práce Distribuce orlů, ponechání prázdného místa; malíř Jean-Baptiste Regnault, nicméně, odmítl vzít ji z jeho obrazu svatby Jérôme Bonaparte.[64]

Nejpopulárnějším uměleckým trhem v Paříži byla galerie Palais-Royal, kde měla svá malá studia a showroomy více než padesát umělců. Umělci v galerii pracovali pro širokou klientelu; Pařížané si mohli nechat vymalovat portrét za třicet franků nebo profil za dvanáct franků. Mnoho umělců tam mělo také své rezidence, v pátém patře. [64]

Konec říše

Bitva o Paříž

V lednu 1814, po Napoleonově rozhodující porážce u Bitva u Lipska v říjnu 1813 napadly spojenecké armády Rakouska, Pruska a Ruska s více než pět set tisíci muži Francii a zamířily do Paříže. Napoleon opustil Tuilerijský palác na frontu 24. ledna a zanechal po sobě císařovnu a svého syna; už je nikdy neviděl. Velel pouze sedmdesát tisíc mužů, ale zvládl dovednou kampaň. .[65] V Paříži byla většina Pařížanů zoufale unavená válkou. Od doby Ludvíka XIV. Neměla Paříž žádné zdi ani jiné významné obranné práce. Napoleonův vlastní ministr zahraničí, princ Talleyrand, tajně komunikoval s carem Alexander I.; 10. března mu napsal, že Paříž není bráněna, a vyzval ho, aby pochodoval přímo do města. [66]

29. března císařovna Marie-Louise a její syn v doprovodu 1200 vojáků Staré gardy opustili Paříž a mířili k zámku Blois v údolí Loiry. 30. března kombinovaná ruská, rakouská a pruská armáda s 57 000 vojáky pod Karl Philipp, princ Schwarzenberg, zaútočil na Paříž, kterou bránil maršál Auguste de Marmont a maršál Édouard Mortier, duc de Trévise se čtyřiceti jedna tisíci muži. Schwarzenberg poslal zprávu francouzským velitelům a vyhrožoval zničením města, pokud se nevzdají. Po dni hořkých, ale nerozhodných bojů na Montmartru v Belleville, u bariér Clichy a Patin a v lomech Buttes de Chaumont, kde bylo na každé straně zabito asi sedm tisíc vojáků, Mortier pochodoval se svými zbývajícími jednotkami na jihozápad z města, zatímco Marmont s jedenácti tisíci muži vstoupil do tajných jednání se Spojenci. Ve dvě hodiny ráno 31. března pochodoval Marmont své vojáky na dohodnuté místo, byl obklopen spojeneckými vojáky a vzdal své síly a město. Napoleon se o této zprávě dozvěděl, když byl v Juvisy, jen čtrnáct mil od města; okamžitě odešel do Fontainebleau, kde dorazil 31. června v 6:00, a 4. dubna se vzdal trůnu. [67]

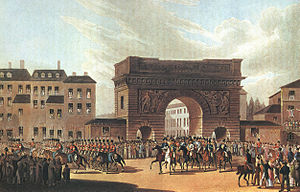

Ruská armáda vedená Alexandrem I. vstoupila 31. března do Paříže Porte Saint-Denis. Někteří Pařížané je přivítali, mávali bílými vlajkami a na znamení dobré vůle měli bílou. Špioni v Paříži pro krále Ludvíka XVIII., Který čekal v anglickém exilu, nepochopili symboliku bílých vlajek a oznámili mu, že Pařížané mávají symbolickou barvou dynastie Bourbonů a netrpělivě očekávají jeho návrat.[68] Talleyrand přivítal cara v jeho vlastním sídle; měl připravený seznam ministrů prozatímní vlády. Zorganizovaný Talleyrandem 1. dubna vyzval předseda Generální rady Seiny k návratu Ludvíka XVIII. francouzský senát zopakoval odvolání dne 6. dubna. Král se vrátil do města 3. května, kde ho s radostí přivítali monarchisté, ale lhostejnost většina Pařížanů, kteří prostě chtěli mír. [69]

Návrat monarchie a sto dní

Paříž byla obsazena pruskými, ruskými, rakouskými a britskými vojáky, kteří se utábořili v Bois de Boulogne a na otevřené krajině podél Champs Élysées, a zůstali několik měsíců, zatímco král obnovil královskou vládu a nahradil bonapartisty svými vlastními ministry, mnozí z nich se s ním vrátili z exilu. Nespokojenost Pařížanů rostla s tím, jak nová vláda, po vedení nových náboženských autorit jmenovaných králem, vyžadovala, aby všechny obchody a trhy zavřely, a v neděli zakázaly jakýkoli druh zábavy nebo volnočasových aktivit. Král byl zvláště neoblíbený u bývalých vojáků a pracovníků, kteří trpěli vysokou nezaměstnaností. Byly zvýšeny daně, zatímco britským dovozům bylo umožněno vstupovat bez cla, což mělo za následek, že pařížský textilní průmysl byl velmi rychle z velké části uzavřen. [70]

Na začátku března 1815 Pařížané byli ohromeni zprávou, že Napoleon opustil svůj exil na Elbě a byl zpět ve Francii, na cestě do Paříže. Louis XVIII uprchl z města 19. března a 20. března byl Napoleon zpět v Tuilerijském paláci. Nadšení pro císaře bylo vysoké mezi dělníky a bývalými vojáky, ale ne mezi běžnou populací, která se obávala další dlouhé války. Během stovek dnů mezi návratem z Elby a porážkou u Waterloo strávil Napoleon tři měsíce v Paříži a usilovně rekonstruoval svůj režim. Zorganizoval velké vojenské recenze a přehlídky, obnovil trikolorní vlajku. Chtěl se ukázat spíše jako konstituční monarcha než jako diktátor, zrušil cenzuru, ale osobně zkontroloval rozpočty pařížských divadel. Pokračoval v práci na několika svých nedokončených projektech, včetně Sloní fontány v Bastille, nového trhu v Saint-Germain, budovy ministerstva zahraničí v Quai d'Orsay a nového křídla Louvru. Divadelní konzervatoř, uzavřená Bourbonovými, byla znovu otevřena s hercem François-Joseph Talma na fakultě a Denon byl obnoven na pozici ředitele Louvru.[71]

V dubnu 1815 se však nadšení pro císaře zmenšilo, protože se válka ukázala jako nevyhnutelná. Branná povinnost byla rozšířena na ženaté muže a jen vojáci povzbuzovali císaře, když prošel kolem. 1. června se na Champs de Mars konal obrovský obřad, který oslavoval referendum o schválení Acte Additionnel, nový zákon, který jej ustanovuje jako konstitučního monarchu. Napoleon měl na sobě fialové roucho a promluvil k davu 15 000 sedících hostů a davu dalších stotisíc osob, kteří stáli za nimi. Ceremonie zahrnovala pozdrav sta děl, náboženský průvod, slavnostní přísahy, písně a vojenskou přehlídku; byla to poslední velká napoleonská událost, která se ve městě konala, než císař 12. června odletěl na frontu a jeho případná porážka u Waterloo 18. června. [72]

Chronologie

- 1800

- 13. února - Banque de France vytvořeno.

- 17. února - Napoleon reorganizoval město do dvanácti okrsků, každý se starostou s malou mocí, pod dvěma prefekty, jedním pro policii a druhým pro správu města, které oba jmenovali.[73]

- 19. února - Napoleon vyrábí Tuilerijský palác jeho bydliště.

- 1801

- Počet obyvatel: 548 000 [74]

- 12. března - Napoleon nařizuje vytvoření tří nových hřbitovů mimo město; Montmartre na sever; Père-Lachaise na východ a Montparnasse na jih [75]

- 15. března - Napoleon objednává stavbu tří nových mostů: Pont d'Austerlitz, Pont Saint-Louis a Pont des Arts.

- 1802

- 1803

- 9. srpna - Robert Fulton předvádí první parník na Seině. Organizuje také výstavy panoramatických obrazů, kde se nyní nachází Passage des Panoramas.[77]

- 24. září - Pont des Arts, první železný most v Paříži, se otevírá veřejnosti. Chodci platí za přechod pět centimů.[77]

- 1804

- 2. prosince - Napoleon I. korun sám Císař francouzštiny v katedrále v Notre Dame de Paris.

- Hřbitov Père Lachaise zasvěcen.[78]

- První ocenění Čestná legie u Invalidovny. První hôtel de Salm se stává Palais de la Légion d'honneur.

- Rocher de Cancale restaurace se otevře.

- 1805

- 4. února - Napoleon nařizuje nový systém čísel domů, počínaje Seinou, se sudými čísly na pravé straně ulice a lichými čísly na levé straně.

- 1806

- 2. května - vyhláška nařizující stavbu čtrnácti nových fontán, včetně Fontaine du Palmier na Place du Châtelet, zajistit pitnou vodu.

- 7. Července - položen první kámen pro Arc de Triomphe du Carrousel, na Place du Carrousel, mezi Tuilerijským palácem a Louvrem.

- 8. srpna - položen první kámen pro Arc de Triomphe na Étoile. Slavnostně otevřeno 29. Července 1836, za vlády Louis Philippe.

- 24. listopadu - Zahájení provozu Pont d'Austerlitz.

- 2. prosince - vyhláška nařizující vytvoření „chrámu slávy“ věnovaného vojákům napoleonských armád na místě nedokončeného kostela Madeleine.

- 1807

- Počet obyvatel: 580 000 [74]

- 13. ledna - Pont d'Iéna slavnostně otevřen.[79] a Théâtre des Variétés[80] otevře se.

- 13. června - vyhláška k výstavbě rue Soufflot na levém břehu, na ose Panteon.

- 29. července - vyhláška o snížení počtu divadel v Paříži na osm; the Opera, Opéra-Comique, Théâtre-Français, Théâtre de l'Impératrice (Odéon); Varieté, Variétés, Ambigu, Gaîté. The Opéra Italien, Cirque Olympique a Théâtre de Porte-Saint-Martin byly přidány později.[81]

- 1808

- 2. Prosince - dokončení Ourcq kanál, přináší do Paříže čerstvou pitnou vodu 107 kilometrů.[79]

- 2. prosince - První kámen položený na sloní fontáně Place de la Bastille. Byla dokončena pouze verze dřeva a sádry v plné velikosti.

- 1809

- 16. srpna - otevření květinového trhu dne quai Desaix (Nyní Quai de Corse).

- 1810

- 5. února - Pro účely cenzury je počet tiskáren v Paříži omezen na padesát.

- 2. dubna - Náboženský obřad sňatku Napoléona s jeho druhou manželkou, Marie-Louise Rakouska, v Salon carré Louvru.

- 4. Dubna - položen první kámen pro palác Ministerstva zahraničních věcí na Libereckém kraji quai d'Orsay. To bylo dokončeno v roce 1838.

- 15. Srpna - dokončení Umístěte Vendôme sloup, vyrobený z 1200 zajatých ruských a rakouských děl [79]

- Katakomby renovovaný.

- 1811

- Počet obyvatel: 624 000 [74]

- 20. března - narození Napoléon François Charles Joseph Bonaparte, Římský král, syn Napoléona I. a císařovny Marie-Louise, v Tuileries.

- 18. září - organizován první prapor pařížských hasičů.[79]

- 1812

- The Sûreté, vyšetřovací kancelář pařížské policie, založená Eugène François Vidocq.

- 1. března - Voda z pařížských fontán je vyráběna zdarma.

- 1814

- 30. března - The Bitva o Paříž. Město je bráněno Marmont a Mortier. Je odevzdáno ve 2 hodiny ráno 31. března.

- 31. března - car Alexander I. z Ruska a král Vilém I. Pruský vstoupit do Paříže, v čele jejich armád.[82]

- 6. dubna - Abdikace Napoleona. Francouzský senát se obrací na Kinga Ludvík XVIII vzít korunu.

- 3. května - Louis XVIII vstupuje do Paříže okupované spojeneckými armádami.

- 1815

- 19. března - Louis XVIII opouští Paříž o půlnoci a Napoleon se vrací 20., na začátku Sto dní.

- Po bitva u Waterloo, Paříž je opět obsazena, tentokrát Sedmá koalice.

Reference

Poznámky a citace

- ^ Héron de Villefosse, René, Histoire de Paris, str. 299

- ^ Combeau 1999.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 57.

- ^ FIERRO 2003, str. 57.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 58.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 90.

- ^ A b Fierro 2003, str. 13.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 84-87.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 72-73.

- ^ Fierro, 2003 a strana 68-72.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 65-68.

- ^ Deterville, “Le Palais-Royal ou les vyplňuje en bon fortune, (1815), Paříž, Lécrivain. Citováno ve Fierro, strana 67-68.

- ^ Chabrol de Volvic, Statistiky znovu v Paříži a v departementu Seina, Paříž, Impremerie Royal, 1821-1829, 4 objemy

- ^ Lachaise 1822, str. 169.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 239-242.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 245-250.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 251-252.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 191.

- ^ Fierro, str. 195-206.

- ^ Fierro 206-213.

- ^ A b Fierro 2003, str. 23-24.

- ^ Fierro, 2003 a strana 24.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 43-45.

- ^ Berkheim, Karl Gustav vonLettres sur Paris, ou Correspondance de M *** dans les annees 1806 et 1807„Heidelberg, Mohr et Zimmer, 1809. Citied in Fierro, 2003. S. 45.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 45-47.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 254.

- ^ A b Fierro 2003, str. 262.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 266.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 32-34.

- ^ Hilliard 1978 216-219.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 37.

- ^ Hillairet, str. 242.

- ^ A b Héron de Villefosse, René, ‘‘ Histoire de Paris ’’, s. 303

- ^ Poumies de la Siboutie, Francois Louis, Souvenirs d'un medecin a Paris (1910), Paříž, Plon. Citováno Fierrem v La Vie des Parisiens sous Napoleon, str. 9

- ^ Fierro 1996, str. 360.

- ^ Chaptal, Jean Antoine Claude, Mes Souvenirs sur Napoléon, Paříž, E. Plon, 1893. Citováno Fierrem v La Vie des Parisiens sous Napoléon, str. 38.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 34-35.

- ^ Jouhaud 1809, str. 37.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 52.

- ^ A b C d Fierro 2003, s. 267–272.

- ^ Berkheim 1807, str. 38-56.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 248-253.

- ^ A b Berkheim 1807, str. 248-253.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 278-279.

- ^ Berkheim 1809, str. 65-66.

- ^ A b Fierro 2003, str. 286-287.

- ^ La peinture en cinemascope et a 360 stupněFrancois Robichon, Beaux Arts časopis, září 1993

- ^ Hillairet 1978, str. 244.

- ^ Fierro 1996, str. 919-920.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 187-189.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 186-187.

- ^ A b C Fierro 2003, str. 110-113.

- ^ A b Fierro 2003, str. 120-123.

- ^ A b Berkheim 1809, str. 42-50.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 146.

- ^ Kotzebue, 1805 a stránky 266-270.

- ^ Poumiés de La Siboutie, François Louis, Souvenirs d'un médecin a Paris, 1910, str. 92-93.

- ^ Fierro, 2003 a strana 298.

- ^ A b Fierro 2003, str. 308.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 311.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 316.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 317.

- ^ Fierro 2003, str. 318-319.

- ^ A b Fierro 2003 314 až 315.

- ^ Roberts 2014, str. 688-700.

- ^ Roberts 2014, str. 708-709.

- ^ Roberts 2014, str. 799.

- ^ Fierro 1996, str. 151.

- ^ FIERRO 1996, str. 612.

- ^ FIERRO 1996, str. 152.

- ^ Roberts 2014, str. 746-747.

- ^ Roberts 2014, str. 748-750.

- ^ Fierro 1996, str. 206.

- ^ A b C Combeau, Yvan, Histoire de Paris (2013) s. 61

- ^ Fierro 1996, str. 610.

- ^ Andrew Lees; Lynn Hollen Lees (2007). Města a tvorba moderní Evropy, 1750–1914. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-83936-5.

- ^ A b Fierro, Alfred, Histoire et dictionnaire de Paris, str. 610.