Bitva o Kapyong - Battle of Kapyong

| Bitva o Kapyong | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Část Čínské jarní útoky v Korejská válka | |||||||

Kapyong, Jižní Korea | |||||||

| |||||||

| Bojovníci | |||||||

| Velitelé a vůdci | |||||||

| Zúčastněné jednotky | |||||||

| Síla | |||||||

| Jeden brigáda | Jeden divize | ||||||

| Ztráty a ztráty | |||||||

| 47 zabito 99 zraněných | ≈1 000 zabito | ||||||

The Bitva o Kapyong (korejština: 가평 전투, 22–25. Dubna 1951), také známý jako Bitva o Jiaping (čínština : 加 平 战斗; pchin-jin : Jiā Píng Zhàn Dòu), se bojovalo během Korejská válka mezi Velení OSN (OSN) - především Kanady, Austrálie a Nového Zélandu - a Číňané Lidová dobrovolnická armáda (PVA). K boji došlo během Čínské jarní útoky a viděl 27. britská brigáda společenství vytvořit blokovací pozice v údolí Kapyong, na klíčové trase na jih do hlavního města, Soul. Dva přední prapory -3. prapor, královský australský pluk (3 RAR) a 2. prapor, kanadská lehká pěchota princezny Patricie (2 PPCLI) - podporováno dělostřeleckou baterií z Královský pluk novozélandského dělostřelectva, obsazené pozice obkročmo nad údolím a spěšně vyvinutou obranu. Jako tisíce vojáků z Armáda Korejské republiky (ROK) se začal stahovat údolím, PVA infiltrovala pozici brigády pod rouškou tmy a během večera a do následujícího dne zaútočila na Australany na kopci 504.

Přestože 27. brigáda byla v přesile, držela své pozice do odpoledne, než byli Australané konečně staženi do pozic v zadní části brigády, přičemž obě strany utrpěly těžké ztráty. PVA poté obrátila svou pozornost na Kanaďany na kopci 677, ale během prudké noční bitvy je nedokázali vytlačit. Boje pomohly otupit ofenzívu PVA a akce Australanů a Kanaďanů v Kapyongu byly důležité při napomáhání, aby se zabránilo průlomu na centrální frontě OSN a nakonec zajetí Soulu. Dva prapory nesl hlavní nápor útoku a zastavil celý PVA divize během těžce bojující obranné bitvy. Následujícího dne se PVA stáhla zpět do údolí, aby se přeskupila. Dnes je bitva považována za jednu z nejslavnějších akcí, které bojovaly Australan a kanadský armády v Koreji.

Pozadí

Vojenská situace

Protiofenzíva OSN v období od února do dubna 1951 byla s USA do značné míry úspěšná Osmá armáda tlačí PVA na sever od Řeka Han v době Provoz Killer, zatímco Soul byl znovu dobyt v polovině března Provoz Ripper a síly OSN se opět přiblížily 38. rovnoběžka.[3] Bez ohledu na napjatý vztah mezi velitelem OSN, Všeobecné Douglas MacArthur a americký prezident Harry S. Truman vedl k MacArthurovu odvolání vrchním velitelem a jeho nahrazení Všeobecné Matthew B. Ridgway.[4] V důsledku toho dne 14. dubna 1951 generál James Van Fleet nahradil Ridgwaye jako velitele osmé armády USA a sil OSN v Koreji. Ridgway odletěl ve stejný den do Tokia, aby nahradil MacArthura.[5] Mezitím ofenzíva pokračovala řadou krátkých výpadů. Provoz odvážný, na konci března, tlačil dopředu k Bentonova linie, 8 kilometrů (5 mil) jižně od 38. rovnoběžky, zatímco Provoz Robustní na začátku dubna tlačil jen na sever od 38. rovnoběžky k Kansas linka. Nakonec v polovině dubna další postup přesunul americkou osmou armádu k Utah linka.[6]

V návaznosti na Bitva o Maehwa-San the 27. britská brigáda společenství si užil období v USA IX. Sbor rezervy, protože síly OSN pokračovaly v neustálém tlaku na sever.[7] V dubnu 1951 se brigáda skládala ze čtyř pěších praporů, jednoho australského, jednoho kanadského a dvou britských, včetně: 3. prapor, královský australský pluk; 2. prapor, kanadská lehká pěchota princezny Patricie; 1. prapor, Middlesex Regiment a 1. prapor, Argyll a Sutherland Highlanders. Brigádní generál Basil Coad 23. března odletěl ze soucitu na dovolenou do Hongkongu a brigáda byla nyní pod velením brigádního generála Brian Burke.[4] V přímé podpoře byla 16. polní pluk, královské novozélandské dělostřelectvo (16 RNZA) s 3,45 palce (88 mm) 25 liber polní zbraně.[8][9] 3 RAR byla pod velením podplukovníka Bruce Ferguson.[10] 2 PPCLI v tuto chvíli velil podplukovník James Stone.[11] Brigáda rozmístěná v ústředním sektoru byla součástí amerického IX. Sboru, který zahrnoval také USA 24. pěší divize, ROK 2. pěší divize, USA 7. pěší divize a ROK 6. pěší divize pod celkovým velením Generálmajor William M. Hoge.[12][13]

Během této doby byla 27. brigáda připojena k 24. divizi USA a na konci března postupovala na sever údolím Chojong a dosáhla Bentonova linie 31. března. Brigáda byla poté propuštěna a postupovala s IX. Sborem do hlubokého a úzkého údolí řeky Kapyong, 10 kilometrů na východ.[14] Od 3. dubna se 27. brigáda přesunula dále proti proudu řeky a během příštích dvanácti dnů postupovala v rámci operace Rugged o 30 kilometrů (19 mil). Přestože údolí PVA nedrželo na síle, bylo dovedně bráněno malými skupinami pěších kopaných na vrcholcích kopců, které ho přehlédly. Postupující podél přilehlých kopců a hřebenů zachytila brigáda po sobě jdoucí pozice a před dosažením velkého odporu narazila na těžký odpor Kansas linka 8. dubna.[6] Po krátké provozní pauze postoupil o 5 kilometrů dál k Utah linka začalo 11. dubna, den po MacArthurově propuštění. Odpor PVA se znatelně posílil a počáteční cíle brigády byly Middlesexem zachyceny až 13. dubna.[15]

Přístup k Utah linka dominovaly dva kopce 900 metrů (3 000 stop) - funkce „Sardine“ 1 kilometr na sever a „Salmon“ dalších 800 metrů na sever. Middlesex byl odrazen během opakovaných pokusů o dobytí Sardinky 14. dubna, než byl úkol přidělen 3 RAR.[15] Společnost, 3 RAR následně dobyla hřeben, zabila 10 PVA a zranila dalších 20 za ztrátu osmi zraněných Australanů.[16] Následujícího rána byl Salmon zajat společností C, aniž by vystřelil, uprostřed odporu světla. PVA ostřelování po jeho dopadení mělo za následek dva muže zraněno, zatímco nálety poté rozbil pokus o protiútok PVA.[17] Mezitím 2 PPCLI pokračovaly ve svém postupu na pravém křídle a 15. dubna zachytily funkci „Turbot“ (Hill 795). Kanaďané, kteří čelili rázné akci zdržující PVA na po sobě následujících pozicích, nezachytili svůj konečný cíl - funkci „Pstruh“ (Hill 826) - až do následujícího rána.[18]

Předehra

Protichůdné síly

Po dosažení Utah linka, 27. brigáda byla stažena zepředu dne 17. dubna a předala své pozice 6. divizi ROK. Burke následně objednal své prapory do záložních pozic severně od dříve zničené vesnice Kapyong, na hlavní silnici ze Soulu na východní pobřeží.[19] Inteligence naznačila, že se blíží nová ofenzíva PVA, a zatímco se brigáda usadila, aby si odpočinula, zůstala ve výpovědi tři hodiny, aby se přesunula na podporu IX. Sboru.[20] Poté, co Britové byli v provozu nepřetržitě posledních sedm měsíců, chtěli Britové uvolnit většinu brigády během jejího období v záloze. Dva britské prapory - Argylls a Middlesex - by byly nahrazeny dvěma novými prapory z Hongkongu, zatímco Burke a velitelství 27. brigády by byly nahrazeny brigádním generálem George Taylor a velitelství 28. brigády koncem dubna. Kanaďané měli naplánovaný přesun do nově vznesené 25. kanadská brigáda v květnu jako součást zvýšeného závazku Kanady k válce. Předsunuté strany z velitelství brigády a Argyllů odletěly do Soulu na cestě do Hongkongu 19. dubna, zatímco zbývající britské prapory byly naplánovány k odletu o dva týdny později.[20][21] 3 RAR se neotočily a zůstaly po celou válku součástí brigády, místo toho fungovaly na samostatném výztužném systému.[20][22]

Mezitím začalo plánování pro Provoz Dauntless, cesta 30 kilometrů (19 mi) do Železný trojúhelník —Klíčová oblast koncentrace PVA / KPA a komunikační spojení v centrálním sektoru mezi Chorwon a Kumwha na jihu a Pchjonggang na severu. Pohotovostní plánování zahrnovalo také opatření proti další ofenzivě PVA, v níž by osmá armáda USA provedla zpožďující obranu na po sobě jdoucích pozicích.[20] Další náznaky bezprostřední komunistické ofenzívy - včetně viditelného posílení dělostřelectva a logistických systémů PVA / KPA - vedly Ridgwaye k tomu, aby nařídil Van Fleet nevyužívat žádné příležitosti nad rámec Wyoming Line. Ridgway s jistotou rozšířil rozsah ofenzívy a určil sekundární objektivní linii ve východním sektoru známou jako Alabama Line. Osud by však zasáhl a Van Fleet zahájil svou ofenzívu 21. dubna, ale následující noc ho potkala mnohem silnější ofenzíva PVA / KPA.[5]

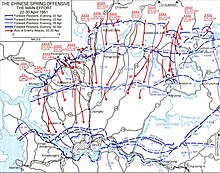

The Čínské jarní útoky —Také známá jako čínská kampaň páté fáze, First Impulse - předpokládala úplné zničení USA Já a IX sbor nad řekou Han, zahrnující tři PVA Armádní skupiny —Skupiny 3., 9. a 19. armády — a tři sbory KPA — the Já, III a V. sbor —Pod celkovým velením Peng Dehuai.[23][24][25][poznámka 1] S okamžitým cílem dobytí Soulu byla ofenzíva zahájena 22. dubna na dvou širokých frontách: hlavní tah přes Řeka Imjin v západním sektoru v držení amerického I. sboru zahrnujícího 337 000 vojáků jedoucích směrem k Soulu a sekundární úsilí zahrnující 149 000 vojáků útočících dále na východ přes Řeka Sojang v centrálních a východních sektorech, přičemž spadají především do amerického IX. sboru, a v menší míře do USA X Corps „sektor.[26] Ofenzívu podpořilo dalších 214 000 vojáků PVA; celkem více než 700 000 mužů.[5] V rámci přípravy byla bitva ztvrdlá 39. a 40. armáda 13. skupiny armád převedena do 9. skupiny armád pod celkovým velením Song Shi-Lun, a Velitel Wen Yuchen 40. armády dostal za úkol zničit 6. divizi ROK a zároveň zablokovat posily OSN směrem k řece Imjin v Kapyongu.[27][poznámka 2]

Ofenzívě čelilo 418 000 vojáků OSN, včetně 152 000 ROK, 245 000 Američanů, 11 500 Britského společenství a 10 000 vojáků z jiných zemí OSN.[5] Jelikož však osmá armáda USA nebyla dostatečně silná, aby zabránila velkým průnikům podél její linie, brzy se kolem jejích boků přehnaly masy pěchoty PVA a obklopily celé formace ve snaze odříznout jejich stažení.[28] Stál přímo v cestě hlavního útoku PVA směrem na Soul v sektoru I. sboru 29. britská brigáda. Stánek brigády na řece Imjin odložil na dva dny dvě divize PVA a nakonec pomohl zabránit zajetí Soulu, ale vyústil v těžké ztráty v jednom z nejkrvavějších britských bojů války. Během bojů většina z 1. prapor, Gloucestershire Regiment byli zabiti nebo zajati během tvrdohlavého odporu u Bitva u řeky Imjin který viděl velícího důstojníka - podplukovníka James Carne - udělil Viktoriin kříž poté, co byl jeho prapor obklíčen.[29] Nakonec 29. brigáda utrpěla na obranu obrany 1 091 obětí Kansas linka, a přestože zničili velkou část 63. armády PVA a způsobili téměř 10 000 obětí, ztráta Glosters způsobila polemiku v Británii a uvnitř velení OSN.[30] Mezitím dále na východ v sektoru IX. Sboru PVA 118. divize, 40. armáda a 60. divize, 20. armáda připraven zaútočit na 6. divizi ROK v noci ze dne 22. dubna.[31]

Bitva

Jihokorejský kolaps, 22. – 23. Dubna 1951

ROK držely pozice na severním konci údolí Kapyong a od osvobození 27. brigády postoupily o 10 kilometrů (6,2 mil).[12] Avšak v očekávání útoku PVA divizní velitel - generál Chang Do Yong - zastavil svůj postup v 16:00 a nařídil svým dvěma útočným plukům - 19. a 2. pěší pluk —Vázat se a rozvíjet obranné pozice. Mezitím 7. pěší pluk obsadil rezervní pozice hned za předními pluky.[32][33] Utrpení reputace nespolehlivosti v obraně bylo ROK podpořeno připojením novozélandských děl a baterie 105 milimetrů (4,1 palce) Houfnice M101 z 213. amerického praporu polního dělostřelectva.[34][35] Bez ohledu na to, že zůstala jen jedna hodina na zastavení postupu a zesílení obrany, byly přední jednotky ROK schopny obsadit pouze několik poloh na vrcholcích kopců, přičemž ponechaly odkrytá údolí a boky.[33] Dvě divize PVA - 118. a 60. divize - zasáhly v 17:00 a snadno pronikly četnými mezerami mezi špatně organizovanými obrannými pozicemi.[33] Pod tlakem po celé přední straně obránci téměř okamžitě ustoupili a brzy se zlomili. Když opustili zbraně, vybavení a vozidla, rozpadli se a začali proudit na jih z hor a údolím a do 23:00 byl Chang nucen přiznat, že ztratil veškerou komunikaci se svými jednotkami.[36] V 04:00 bylo rozhodnuto stáhnout Novozélanďany, aby se zabránilo jejich ztrátě; po zprávách o tom, že se ROK staví, jim bylo nařízeno příštího rána zpět do údolí s Middlesexem, který je doprovázel jako ochranu. Za soumraku bylo jasné, že ROK se ve skutečnosti zhroutil a zbraně byly znovu staženy.[34][36]

Mezitím USA 1. námořní divize držel pevně proti PVA 39. armádě na východ a stažení ROK nechalo jejich křídlo odkryté.[36] Avšak u 39. a 40. armády PVA, jejímž úkolem bylo chránit pouze východní křídlo 9. skupiny armád před možnými protiútoky 1. námořní divize, PVA tuto příležitost nevyužila a Američané zůstali relativně nerušeni.[36][37] Přestože přední pozice OSN v sektorech amerického I. sboru a amerického sboru IX byly stále neudržitelné, protože PVA využívala mezery mezi formacemi, Van Fleet nařídil stažení Kansas linka dopoledne. Hoge následně nařídil americkým mariňákům vytvořit novou obrannou pozici za hranicemi Řeka Pukhan, mezi Vodní nádrž Hwachon a novou pozici, kterou má obsadit 6. divize ROK. Hogeův plán se opíral o reformu ROK a nabízení určitého odporu, a přestože byl opožděně ustanoven zadní voj 2 500 mužů, nebyl v žádném stavu k boji.[38] Hoge se bál průlomu a nařídil 27. brigádě, aby jako rezerva sboru vytvořila obranné pozice severně od Kapyong odpoledne 23. dubna preventivně pro případ, že by se ROK nepodařilo udržet, pověřil je blokováním dvou přístupů do vesnice a zabránil PVA v přerušení trasy 17, klíčové trasy na jih do Soulu a důležitého hlavní napájecí trasa.[34][39]

Brigáda byla nyní redukována na tři prapory, protože Argyllové byli staženi Pusan těsně před bitvou, v rámci přípravy na jejich nalodění. Middlesex byl také v pohotovosti pro nalodění a byl držen v záloze.[40] Vzhledem k tomu, že šířka údolí bránila vytvoření nepřetržité lineární obrany, byl Burke nucen umístit své dva dostupné prapory na nejvyšší body na obou stranách, přičemž 3 RAR obsadily kopec 504 na východ od řeky a 2 PPCLI zabírající Hill 677 na západ. Mezitím byl Sudok San (vrch 794) na severozápad - mohutný kopec vysoký téměř 800 metrů (2 600 ft) - nutně ponechán bez ochrany. Společně tyto tři kopce vytvořily přirozeně silnou obrannou pozici, vhodnou k blokování velkého postupu.[41] Bez ohledu na to pozice brigády trpěla řadou nedostatků, byla vystavena bez ochrany boků, zatímco centrální sektor nebyl obsazen, protože Middlesex byl se zbraněmi pryč na severu. Stejně tak měla brigáda až do návratu Novozélanďanů malou dělostřeleckou podporu; pokud by tedy velké PVA síly dorazily dříve, než se tyto dvě jednotky vrátily, budou vpřed společnosti bez podpory a budou muset akceptovat pravděpodobnost, že budou přerušeny. 3 RAR - jejíž komunikační linka probíhala 4 kilometry exponovaným centrálním sektorem údolí - bude obzvláště vystavena.[41]

Každý z praporů byl rozmístěn po vrcholcích a svazích samostatně společnost -rozměrné obranné pozice, které vytvářejí řadu silných stránek napříč 7 kilometrů vpředu. Vzhledem k velkému množství terénu, které bylo třeba bránit, byla každá ze společností široce rozšířena a nebyla schopna nabídnout vzájemnou podporu. Místo toho se každá četa vzájemně podporovala, přičemž každá rota přijala všestrannou obranu. Velitelství brigády zůstalo v údolí, 4 kilometry na jih.[42] Vzhledem k tomu, že novozélandští střelci stále podporovali ROK, umístil americký IX. Sbor baterii 105 milimetrových houfnic z 213. praporu polního dělostřelectva a dvanáct 4,2 palců (110 mm) Malty M2 roty B, 2. prapor chemické malty, pod velením 27. brigády. Patnáct Shermanské tanky podporu poskytla také společnost A Company, 72. prapor těžkých tanků USA.[8][9]

Kanaďané následně obsadili kopec 677 a začali kopat a rozmístit svých šest Kulomety Vickers v sekcích přidat hloubku a pomocí obranných palebných úkolů překrýt mezery ve svých pozicích.[43] Mezitím Australané obsadili kopec 504, přičemž D Company držel samotný vrchol, A Company pobřežní čáru, která se táhla dolů na severozápad, a B Company malý kopec u řeky, zatímco C Company byla v záloze vzadu podnět[41] V reakci na požadavky amerického sboru IX. Burke nařídil Fergusonovi, aby umístil své sídlo do nížiny údolí v blízkosti osady Chuktun-ni, aby ovládl odstupující ROK. To by však omezilo Fergusonovo situační uvědomění a jeho schopnost kontrolovat bitvu a zároveň by je nechalo vystaveno infiltraci.[44] Odpoledne se kopalo a stavělo na lehce křovinatých svazích sangars kde se kamenitá půda ukázala jako příliš tvrdá.[26] Za pouhých pár hodin se Australanům podařilo připravit ukvapené obranné pozice, ačkoli úkoly obranné palby nemohly být registrovány jako dělostřelectvo Vpřed pozorovatelé nebyli schopni dosáhnout pozic společnosti až po setmění.[45]

Velitel americké tankové roty - poručík Kenneth W. Koch - nasadil své čety na podporu Australanů. Silnice obcházela východní křídlo vrchu 504 a nabízela nejlepší plochu pro použití brnění. Jedna četa pěti tanků obsadila severní základnu před B Company, aby zabránila PVA používat silnici; další četa obsadila vyvýšeninu na západ s rotou B; zatímco poslední četa a velitelský tank Koch byly rozmístěny poblíž velitelství praporu a pokrývaly brod, kterým silnice překročila řeku Kapyong, přibližně 800 metrů jižně od B Company. Možná nerozumně byly tanky rozmístěny bez podpory pěchoty.[41] Velitelský vztah mezi Australany a jejich obrněnou podporou byl také komplikovaný, protože Američané nebyli pod velením, jak by za normálních okolností mohli být, spíše Koch mohl svobodně vést svou vlastní bitvu. Bez ohledu na to, vyzbrojen dělem o délce 76 milimetrů a jedním Ráže .50 a dva Ráže 30 kulomety, M4 Sherman tanky byly impozantní aktiva a značně posílily obranu. Naproti tomu PVA neměla v Kapyongu žádné tanky, zatímco jejich pěchota měla jen několik protitankových raket o rozměrech 3,5 palce (89 mm), kterými jim čelila.[46]

Do 20:00 toho večera velký počet ROK ustupoval zmateně mezerou v linii držené brigádou, většina z nich se pohybovala Australanů.[34] 6. divize ROK se později přeskupila na pozice za 27. brigádou, ale nyní byla snížena na méně než polovinu své původní síly.[35] Mezitím, když se 20. armáda v rámci hlavního úsilí PVA proti Soulu otočila na západ, pokračovala 118. divize PVA ve svém sekundárním postupu dolů údolím Kapyong a úzce sledovala ustupující ROK. 354. pluk, který uháněl severovýchodním údolím, dosáhl australských pozic přibližně o 22:00.[35][Poznámka 3] Záměr zachytit důležitou křižovatku trasy 17 jižně od Kapyongu a s největší pravděpodobností neví o umístění australské blokovací polohy, PVA předvoj zůstali na nízké zemi a rozdělili se, když se blížili k dlouhému, nízkému severojižnímu běžícímu hřebenu, který se tyčil jako ostrov v ústí údolí.[35]

Noční bitva, 23. – 24. Dubna 1951

Poté, co úspěšně zabránila americké 1. námořní divizi v posílení fronty řeky Imjin, obrátila 23. armáda PVA svou pozornost 23. dubna na 27. brigádu.[37][47] Bitva začala v noci z 23. na 24. dubna a pokračovala až do pozdního následujícího dne jako celá 118. divize PVA, celkem asi 10 000 mužů pod velením Deng Yue —Zapojil dva přední prapory 27. brigády.[2][45][48] Počáteční útok PVA na Kapyong zasáhl 3 RAR na kopci 504, zatímco v rané fázi bitvy byli střelci Middlesex a Nový Zéland téměř odříznuti. Odpor Australanů jim však nakonec umožnil bezpečně se stáhnout a Middlesex se poté přesunul do rezervní polohy obkročmo na západním břehu řeky, aby poskytl hloubku obraně brigády.[26] Oba prapory 354. pluku PVA zahájily opakované útoky na dvě přední australské roty na severozápadním výběžku vrchu 504. Útok po útoku hromadných jednotek PVA útok udržoval po celou noc, ale silná obrana Australanů proti pravé křídlo brigády je drželo zpátky, než následující den obrátili pozornost ke Kanaďanům.[41]

S využitím ustupujících vojsk ROK infiltrovala PVA v počátečních fázích bitvy pozici brigády, pronikla mezi společnostmi A a B, 3 RAR obkročila po silnici a do značné míry ji obklopila, než se přesunula do zadních pozic.[26] Australané se ve tmě snažili odlišit PVA od ROK, i když Korejský servisní sbor nosiči připojení k praporu byli schopni poskytnout cennou pomoc obráncům rozlišujícím PVA podle zvuků jejich hlasů.[49] V 21:30 zahájila PVA svůj první útok na přední četu amerických tanků, které byly vyslány na silnici bez podpory pěchoty. Počáteční pohyby byly snadno odrazeny; silnější útok o hodinu později přinutil tanky ustoupit poté, co byli zabiti dva velitelé tanků, včetně velitele čety.[26] PVA poté pokračovala v útoku na Australany na dvou různých osách: jedna proti dvěma vpřed společnostem před vrchem 504 a druhá údolím obkročmo na silnici kolem velitelství praporu.[45] Nakonec se do 23:00 novozélandské dělostřelectvo vrátilo do brigády, ačkoli po zbytek noci poskytovalo jen omezenou podporu.[7][50]

Začaly sondy na pozicích společnosti A a B a během noci došlo k řadě útoků. S využitím nepřímých požárů se PVA nabíral vpřed ve vlnách, ale Australané je museli porazit. Lehké kulomety Bren, Owen samopaly, střelba z pušky a granáty, než se znovu přeskupili a znovu zaútočili.[26] Společnost B - pod velením kapitána Darcyho Laughlina - podporovaná tanky, odehrála každý útok, způsobila těžké ztráty a vynořovala se téměř bez úhony. Laughlinovo velitelské stanoviště bylo vystřeleno řadou PVA, které infiltrovaly postavení společnosti, ale byly rychle vyhnány. Předsunutá základna na severním návrší ohlásila hromadění PVA na jejich bocích ve 23:00, a přestože proti útočníkům bylo namířeno těžké dělostřelectvo, sekce byla nucena přerušit kontakt a stáhnout se do hlavní obranné pozice. Hlavní útok PVA začal v 00:50 a spadl na 4. četu, ale byl rozbit po hodině těžkých bojů. Druhý útok byl zahájen na 6. četě v 03:30, po a finta proti 5 četě. PVA odhodlaně vyrazila vpřed a pronikla australským perimetrem, než byla vyhozena stejně odhodlaným protiútokem 6. čety s tanky Sherman na podporu. V 04:00 byla malá základna za pozicí společnosti napadena více než 50 PVA. Australanové, drženi pouhými čtyřmi muži pod velením svobodníka Raye Parryho, bojovali proti čtyřem samostatným útokům, přičemž během dvaceti minut zabili více než 25 a mnoho dalších zranili. Parry byl později oceněn Vojenská medaile za jeho činy.[51][52] Poslední útok na společnost B byl proveden těsně za úsvitu v 04:45 asi 70 PVA a byl znovu odrazen.[53]

Dále na hřeben čelila společnost - pod vedením majora Bena O'Dowda - těžšího úkolu a pod silným útokem.[54] První sondy začaly ve 21:30 a zaměřily se na 1 četu, která byla nejnižší ze tří čet na západním křídle. Na počáteční kroky poté během následujících tří hodin navázaly hlavní útoky PVA ze tří stran. Navzdory utrpení mnoha obětí PVA pokračovala v útoku, uzavřela se a zaútočila na Australany ručními granáty. Australané také utrpěli mnoho obětí, přičemž více než polovina čety byla zabita nebo zraněna, včetně všech tří brenských střelců. Bránili palbou z ručních zbraní a drželi se proti opakovaným útokům, které se zvyšovaly na frekvenci a síle, jak PVA útočila na hromady vlastních mrtvých a zraněných. Do 01:00 O'Dowd nařídil těm, kteří přežili 1. četu, aby se stáhli přes velitelství roty na novou pozici mezi 2 a 3 čety. Za jeho vedení byl poručík Frederick Gardner později Uvedeno v Expedicích.[53][55] Útoky PVA pak pokračovaly proti 3. četě a trvaly až do 04:30, ačkoli nebyly provedeny se stejnou váhou jako předchozí útoky.[56]

Za úsvitu bylo jasné, že PVA se podařilo proniknout po obvodu mezerou mezi australskými čety, a začali je zasouvat kulomety z defilade pozice zakrytá ohněm strmým poklesem v hřebeni a skrytá silným křovím. V sílícím světle byla četa 1 a 3 brzy přidržena a utrpěla řadu obětí, když se pokoušely získat lepší palebné pozice, aby mohly útočit na své útočníky. V 06:00 byla vyslána bojová hlídka, aby navázala kontakt s ústředím roty, a když úsek cestou dolů prošel falešným hřebenem urychlit linii náhodou narazili na pozice PVA. Okamžitý útok, šest PVA bylo zabito pro ztrátu jednoho Australana a hrozba pro společnost byla odstraněna. O'Dowd poté zahájil protiútok tím, že 3 četa zaútočila na PVA a obsadila původní pozici 1 čety. Do 07:00 se znovu dostali do funkce a PVA byli nuceni ustoupit pod těžkou palbou Australanů na vyvýšeném místě, kteří opět požadovali vysoké mýtné. Noční bitva však stála společnost draho, a mezi mrtvými byli dva novozélandští vpřed pozorovatelé. Celkově utrpěli více než 50 obětí - polovinu své původní síly.[56][57] Mezitím D Company - pod kapitánem Normem Gravenerem - na pravém křídle držela vrchol kopce 504 a v noci nebyla silně zapojena, zatímco C Company - velel kapitán Reg Saunders - byl napaden pouze jednou.[58]

Velitelství praporu, umístěné 1 500 metrů vzadu, se však ocitlo silně stlačené. Chráněno pouze částí Kulomety Vickers, dva 17 liber protitanková děla, útočná pionýrská četa a plukovní policie pod velitelem roty velitele - kapitán Jack Gerke —Boje vzplanuly kolem 22:00, když PVA infiltrovala pozici mezi ustupujícím ROK. Obcházeli velitelství a americké tanky poblíž, obkličovali obránce a vytvářeli blokovací pozice na silnici na jih. Během noci se PVA pokusila namontovat tanky a zničit je granáty a brašny, ale byli zahnáni ohněm. Později jeden z tanků dostal přímý zásah z 3,5palcové rakety, zatímco přední obvod byl silně zasažen útočícími vlnami PVA a byl nucen zpět s těžkými ztrátami. Shermany, kteří dostávali palbu od vojáků PVA obývajících několik domů ve vesnici Chuktun-ni, zasáhli zátaras a několik domů a zabili více než 40 PVA v jediném domě.[58] V 04:00 však musela být vyslána rota z praporu Middlesex, aby pomohla situaci obnovit.[45]

Za úsvitu PVA zintenzivnil útok na obvod velitelství, zabil a zranil převážnou část Středního kulometu a Útočné pionýrské čety a vyhnal je z vyvýšeného místa, které okupovali.[59] Do 05:00 byl PVA ve výškách schopen vystřelit přímo do velitelství praporu níže a Ferguson se rozhodl stáhnout 3 kilometry (1,9 mil) na novou pozici uvnitř obvodu Middlesex. Gerke nařídil svým mužům, aby se postupně stáhli a pohybovali po vozidle po silnici zpět, protože ty, které zůstaly, kryly palbu. Odstoupení bylo úspěšně dokončeno, a když se společnost ústředí konečně shromáždila uvnitř obvodu Middlesexu, bylo Gerkeovi nařízeno zajistit klíčový brod přes řeku Kapyong, 2 kilometry východně, jako možnou cestu stažení z praporu, pokud by později muset odejít z kopce 504.[60] Během odstoupení však dva Australané zůstali pozadu a byli následně zajati PVA: voják Robert Parker, prapor kurýr a soukromé Horace Madden, jeden ze signalizátorů.[61] Za své chování v zajetí byl Madden posmrtně vyznamenán George Cross, po jeho smrti na podvýživu a špatné zacházení.[62][63][poznámka 4] Fergusonův karavan, přestavěný nákladní vůz o hmotnosti dva a půl tuny, se během odtažení zabředl a musel být zničen.[64] Mezitím byla novozélandská dělostřelecká sonda testována také brzy ráno a byla nucena znovu nasadit ve 3:00, zatímco americká minometná rota jednoduše uprchla a opustila většinu svých zbraní a vozidel.[65]

Komunikace mezi 3 RAR a velitelstvím brigády brzy selhala, zatímco ti s předními společnostmi byli také špatní. To bylo způsobeno hlavně velkým počtem ROK ustupujících svou pozicí, která vytrhla linii z velitelského stanoviště, a také vlivem silného provozu vozidel a střelbou na exponovanou linii. Stejně tak přímá rádiová komunikace s předními roty na velitelské síti praporu s novým typem 31 VHF rádia byla blokována členitým terénem kvůli umístění velitelství praporu na nízké zemi ve srovnání s předními roty a požadavkem na přímá viditelnost. Přední roty byly schopny udržovat vzájemnou komunikaci, ale ne s velitelství praporu, zatímco sítě na úrovni roty také fungovaly dobře. Nakonec byl mezi Fergusonem a Burkem udržován kontakt prostřednictvím rádiového přijímače v ústředí praporu Middlesex, zatímco zprávy předním společnostem se spoléhaly na linku a pomalé předávání prostřednictvím společnosti C.[45][66][67] Tyto problémy první noc ještě více zkomplikovaly průběh obrany, přičemž koordinace postupující bitvy padla na O'Dowda.[56][67] Následujícího rána se O'Dowdovi nakonec podařilo projít na a rádiový telefon generálovi v 1. námořní divizi USA. Důstojník nevěřícně si myslel, že to byl čínský agent. Řekl O'Dowdovi, že jednotka již neexistuje a že byla noc předtím vymazána. O'Dowd odpověděl: „Mám pro tebe novinky. Jsme stále tady a my tady zůstáváme.“[68]

Útoky PVA byly zahájeny rychle a agresivně, na podporu položily své lehké kulomety a pokoušely se zavřít, aby zaútočily na australský perimetr granáty. Na rozdíl od některých současných západních účtů PVA nepoužíval lidská vlna taktiky, spíše s využitím taktiky známé jako „jedna strana-dvě strany“, použili shromážděné síly a infiltrace dosáhnout lokální početní převahy a proniknout do mezer mezi předními společnostmi, než se pokusí obklíčit Australany a přitom střílet palbu dopředu, daleko od jejich ohrožených boků.[49] Za normálních okolností by se pokusili uzavřít obranné pozice OSN pomocí temnoty nebo špatné viditelnosti, aby zakryli svůj pohyb a postavili se proti americké vzdušné převaze, než zaútočí hromadnou silou, koordinovanou s úzkou palebnou podporou. Přestože útoky PVA v Koreji byly obvykle dobře naplánovány a úzce podporovány kulometnou, minometnou a dělostřeleckou palbou, byly po zahájení často neproveditelné. To bylo způsobeno hlavně nedostatkem rádiové komunikace pod úrovní praporu, místo toho se spoléhala PVA pískat výbuchy, polnice výzev a běžců k velení a řízení, a přestože jejich minomety o rozměrech 60 milimetrů (2,4 palce) a 81 milimetrů (3,2 palce) poskytovaly obzvláště účinnou nepřímou palebnou podporu, tyto problémy byly opět patrné během bojů v Kapyongu.[49][69] Later, it was estimated that more than 500 PVA were killed by the Australians and the American tanks that supported them.[70]

Meanwhile, on Hill 677 the Canadians had spent the night of 23/24 April in their pits listening to the sounds of the fighting on the Australian front. However, by early morning PVA activity increased and, with the situation deteriorating on the Patricia's right flank, Stone withdrew B Company from their position forward of the feature's summit to strengthen this flank if the Australians were forced to withdraw. Under the command of Major Vince Lilley the company subsequently moved to occupy positions east of Battalion Headquarters on the high ground overlooking the valley road.[71]

Day battle, 24 April 1951

As daylight broke, the PVA now found themselves highly exposed in the open ground in front of the Australians. A and B Company supported by artillery, mortars, and tanks poured heavy fire onto the hapless Chinese, forcing them to withdraw leaving hundreds of casualties behind on the slopes. With the Australians remaining in possession of their original defensive locations the immediate situation had stabilised, although they were now effectively cut-off 4 kilometres (2.5 mi) behind the front.[65] Ammunition, food, and medical supplies were now extremely low throughout the forward area, and with casualty evacuation increasingly difficult, the battalion was at risk of being overrun unless it could be concentrated, resupplied, and supported.[60] As such, in order to avoid each company being isolated and overwhelmed in a series of PVA attacks, at 07:15 B Company was ordered to leave its position and join the other companies on the high ground to form a defendable battalion position. The Australians subsequently withdrew as instructed, taking several dozen PVA prisoners with them that had been captured earlier by a standing patrol.[65] The New Zealand gunners covered their movement across the open valley, laying a kouřová clona to conceal the withdrawal, while the American tanks also provided support. As they moved across the valley the Australians exchanged a number of shots with a small groups of PVA who were still hiding in dead ground and in the riverbed, as well as numerous dead from the fighting the previous night.[72] One hundred and seventy-three dead PVA were counted on the B Company perimeter by the Australians before they departed.[73]

With B Company successfully occupying its new positions, Ferguson moved forward to the hillside below his forward companies aboard a Sherman tank.[74] Just after 09:00, a group of PVA launched an attack at the top of the spur held by C Company. The attack was repulsed, and no further assaults were made against C Company during the day, although they endured sniper fire and mortar bombardment for several hours. Realising the importance of B Company's previous position to a planned counter-offensive, two hours after their withdrawal, Ferguson ordered Laughlin to re-occupy the position which they had just vacated. 27th Brigade would now be reinforced by American troops and their move forward would be facilitated if the PVA were cleared from the small hill that commanded the road through the valley. Likewise, the defence of this position the previous evening had prevented a PVA assault on the western flank of Hill 504. As such, at 09:30 the order to withdraw was rescinded and B Company was tasked to re-occupy the position. In preparation for the company assault on the summit, Laughlin tasked 5 Platoon to assault a small knoll halfway between C Company and the old B Company position. A frontal assault was launched at 10:30, with two sections attacking and one in fire support. Strongly held by a PVA platoon well dug-in in bunkers, the defenders allowed the Australians to approach to within 15 metres (16 yd) before opening fire with machine guns, rifles, and grenades. 5 Platoon suffered seven casualties, including the platoon commander, and they were forced to withdraw under the cover of machine-gun and mortar fire.[72]

4 Platoon under Lieutenant Leonard Montgomerie took over the attack, while a number of American tanks moved in to provide further support. Conducting a right flanking attack, the Australians suffered a number of casualties as they moved across the open ground. Advancing to within 30 metres (33 yd) of the forward trenches, the PVA fire increased. Montgomerie launched a desperate bajonet charge, while a section under Corporal Donald Davie broke in on the right. Amid fierce hand-to-hand fighting the Australians cleared the PVA from the trenches, losing three men. Davie's section was then heavily engaged by machine guns from the rear trenches, and he moved quickly to assault these with his remaining men. Montgomerie reorganised the platoon, and they fought from trench to trench using bayonets and grenades. The Australians then began taking fire from another knoll to their front and, leaving his rear sections to clear the first position, Montgomerie led Davie's section onto the second knoll. Against such aggression the PVA were unable to hold and, although the majority bravely fought to the death, others fled across the open ground. By 12:30 the knoll had been captured by the Australians, with 57 PVA dead counted on the first position and another 24 on the second.[75] A large PVA force was now detected occupying the old B Company position and the Australians were effectively halted halfway to their objective. Before Laughlin could prepare his next move he was ordered to withdraw by Ferguson, and the attempt to dislodge the PVA was subsequently abandoned.[65] During the fighting the tanks had provided invaluable support, moving ammunition forward to B Company, and helping to evacuate the wounded. The entire operation had cost the Australians three killed and nine wounded. For his actions Montgomerie was awarded the Vojenský kříž, while Davie received the Military Medal.[74][76]

Meanwhile, the PVA shifted their attention to D Company, launching a series of relentless assaults against the summit.[65] D Company's position was vital to the defence of Hill 504, commanding the high ground and protecting the Australians' right flank. Commencing at 07:00 the PVA assaulted the forward platoon—12 Platoon, launching attacks at thirty-minute intervals until 10:30. Using mortars to cover their movement, they attacked on a narrow front up the steep slope using grenades; however, the Australians beat the PVA back, killing more than 30 for the loss of seven wounded during six attacks. The New Zealand artillery again played a key role in defeating the PVA attempts, bringing down accurate fire within 50 metres (55 yd) of the Australian positions. However, throughout the fighting the supply of ammunition for the guns had caused severe problems, as the PVA offensive had depleted the stock of 25-pounder rounds available forward of the vzduchová hlava v Soulu. Despite improvements, problems with the logistic system remained and each round had to be used effectively in response to the directions of the artillery Forward Observers which controlled their fire.[77] Although badly wounded, Corporal William Rowlinson was later awarded the Medaile za vynikající chování for his leadership,[52] while Private Ronald Smith was awarded the Military Medal.[76] Lance Corporal Henry Richey was posthumously Mentioned in Despatches after being fatally wounded attempting to evacuate the last of the Australian casualties.[76][78]

Despite their previous failures, the PVA launched another series of attacks from 11:30 and these attacks continued for the next two hours, again targeting 12 Platoon under the command of Lieutenant John Ward. Failing to break through again, the PVA suffered heavy casualties before the assault ended. From 13:30 there was another lull in the fighting for an hour and a half, although D Company continued to endure PVA mortar, machine-gun, and rifle fire. Believing that the battle may continue into the night, Gravener made the decision to pull 12 Platoon back in order to adopt a tighter company perimeter, lest his forward platoon be overrun and destroyed. The movement was completed without incident and, shortly after, the newly vacated position was assaulted by a large PVA force which had failed to detect the withdrawal. The PVA moved quickly as they attempted to establish their position on the northern end of the ridge, only to be heavily engaged by Australian machine-gun and rifle fire, and artillery.[79]

On the Canadian front, B Company, 2 PPCLI completed its redeployment by 11:00 hours. The battalion now occupied a northward-facing arc curving from the summit of Hill 677 in the west to the high ground closest to the river. D Company held the summit on the battalion's left, C Company the central forward slope, while A and B Company held the right flank. The high grass and severe terrain of Hill 677 limited the ability of each company to provide mutual support, however, while at the same time it afforded any attacking force limited avenues of approach, and even less cover or concealment for an assault.[80] 24 April passed with little activity, with the PVA continuing to focus on the Australians across the river. Meanwhile, the Canadians continued to strengthen their defences as reports of growing PVA concentrations came in from the forward companies. Each company was allocated a section of Vickers medium machine guns, as well as three 60-millimetre (2.4 in) mortars. Defensive fire tasks were registered, while additional ammunition was pushed out to the forward companies in the afternoon.[81]

3 RAR withdraws, evening 24 April 1951

Although originally intending on holding until the Australians could be relieved by the US 5. jízdní pluk, Burke had decided during the morning to withdraw 3 RAR, and this had prompted the cancellation of B Company's assault.[74][82] With the Australians facing obklíčení, and mindful of the fate that had befallen the Glosters, Burke had ordered a fighting withdrawal back to the Middlesex area to new defensive positions in rear of the brigade.[83] Indeed, despite holding the PVA at bay throughout the morning and afternoon, the increasing difficulty of resupply and casualty evacuation made it clear that the Australians would be unable to hold Hill 504 for another night in its exposed and isolated positions.[83] Planning for the withdrawal had begun as the PVA renewed their assault on D Company around 11:30, while Ferguson and O'Dowd discussed the withdrawal by radio at 12:30.[84] With the PVA dominating the road south, Ferguson ordered his companies to withdraw along a ridge running 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) south-west from Hill 504, just east of the Kapyong River. The Middlesex position lay a further one kilometre (0.62 mi) south-west of the foot of the ridge and could be reached by the ford secured earlier by Gerke, which would act as the battalion check point for the withdrawal. O'Dowd, as the senior company commander, was subsequently appointed to plan and command the withdrawal.[74] Ferguson saw his role as ensuring that O'Dowd received the support he needed to achieve a clean break, and had as such decided not to move forward to lead the withdrawal himself.[85]

Command of A Company was temporarily handed over to the second-in-command, Captain Bob Murdoch. Přítomen na Bitva u Pakchonu in November 1950, O'Dowd understood first-hand the dangers of withdrawing while in contact. The challenge was to protect the forward platoons as they withdrew from being followed up by the PVA occupying the old B Company positions and from D Company's position after they broke contact. The Australians would also have to clear the withdrawal route of any blocking forces, while at the same time the evacuation of a large number of wounded and PVA prisoners would hamper their movement.[86] As such the timing of the withdrawal would be critical to its success. Consequently, the lead company would not move until mid-afternoon so that the rearguard would be able to use the protection of darkness to break contact, while at the same time offering good observation and fields of fire during the daylight to support the initial moves.[74][86] Orders were delivered at 14:30. B Company would lead the withdrawal down the ridge line, carrying any wounded that still required evacuation, as well as clearing the route and securing the ford near the Middlesex position. C Company would wait for the artillery to neutralise the PVA on the old B Company position, before moving to establish a blocking position behind D Company. A Company would then withdraw to a blocking position behind C Company, in order to allow Gravener and Saunders to establish a clean break. Finally, D Company would withdraw through both C and A Company and set up a blocking position to delay any follow up and allow those companies to withdraw.[87]

After 15:00 an airstrike was called in to dislodge the surviving PVA in front of D Company. However, the attack by two US Marine Corps Korzáři F4U was mistakenly directed at the Australians themselves after their positions were wrongly marked by the spotter plane. Two men were killed and several badly burnt by napalm before the attack was broken off after the company second-in-command—Captain Michael Ryan—ran out under PVA fire waving a marker panel.[65] The company medical orderly—Private Ronald Dunque—was subsequently awarded the Military Medal for his efforts assisting the wounded despite his own injuries.[52][88] The PVA quickly attempted to exploit the chaos, moving against D Company's long exposed eastern flank. 11 Platoon on the main ridge forward of the summit was subjected to a frontal assault; however, unaffected by the napalm, they broke up the PVA attack and inflicted heavy casualties on them. Regardless, further PVA attempts to infiltrate the Australian positions continued into the afternoon.[89][poznámka 5]

The withdrawal was scheduled to begin shortly following the misdirected airstrike, and was to be preceded by an artillery bombardment with high explosive and smoke at 16:00.[poznámka 6] The American tanks were subsequently moved forward to provide cover, and when the New Zealand artillery failed to fire at the appointed hour, they provided the direct fire support. Still in contact, the Australians began to pull back, fighting a number of well-disciplined rearguard actions as the companies leapfrogged each other. Meanwhile, the New Zealand artillery kept the PVA at bay, after it finally commenced firing.[86] B Company had taken 39 PVA prisoners during the earlier fighting, and unable to leave these behind, they were used to carry many of the Australian wounded and much of their equipment as well. O'Dowd's fear that the PVA might have blocked the withdrawal route was not realised, and B Company moved back along the ridge and down to the ford without incident, reaching the Middlesex area after dark. C Company was the next to withdraw, departing at 16:30, just after suffering another casualty from sniper fire. Saunders led his company up the spur and then south down the main ridge without incident, followed by A Company during the next hour with the PVA in close pursuit.[90]

Murdoch had been concerned lest he and his men should be engaged when they reached the Kapyong River in an exhausted condition and with little ammunition. Luck was with the Australians, and due to difficulties of communication and navigation along the ridge line in the dark, elements of A Company had become separated and the last two platoons descended to the river too early to strike the ford. However, reaching a deserted part of the bank they realised their mistake and immediately turned west again, following the river-bank to the ford. The PVA did not follow this sudden final turn and plunged on into the river, giving A Company an unexpected opportunity to break free. The PVA were subsequently detected by the Canadians on Hill 677 and were fired on. Fortunately for the Australians, the Canadian fire did not hit them. This possibility had been foreseen earlier; however, problems with the radio relay between the Canadians and Australians meant that there had been no guarantee that the withdrawing force would not be mistaken for PVA as they crossed the river.[91]

Only D Company—which had been holding the summit and had withdrawn last—was heavily engaged and was unable to move at the scheduled time. The PVA launched a determined assault, preceding it with heavy machine-gun and mortar fire, before attempting to overrun the forward pits. Once again the Australians repelled the PVA assault and Gravener decided to begin to thin out his position before the situation deteriorated further. With one platoon covering their movement, D Company subsequently withdrew, closely pursued by the PVA. During the rapid withdrawal after the final PVA attack, Private Keith Gwyther was accidentally left behind after being knocked unconscious and buried in a forward pit by a mortar round. He regained consciousness some hours later and was subsequently captured by the PVA who had by then occupied Hill 504 and were digging in.[92] Finally, the Australians succeeded in achieving a clean break after dark, and D Company was able to safely withdraw.[83][93] By 23:30 the battalion was clear, completing its withdrawal in good order and intact, and suffering only minimal casualties.[93] Regardless, the previous 24 hours of fighting had been costly for the Australians, resulting in 32 killed, 59 wounded and three captured; the bulk of them in A Company and Battalion Headquarters. Yet their stout defence had halted the assault on the brigade's right flank, and had inflicted far heavier casualties on the PVA before being withdrawn. Significantly for the Australians 25 April was Anzac Day; however, following their successful withdrawal the PVA turned their attention to the Canadians on the left flank.[83]

Defence of Hill 677, 24–25 April 1951

Despite the withdrawal from Hill 504 that evening, 27th Brigade had been reinforced on the afternoon of 24 April by the arrival of the 5th US Cavalry Regiment. The Americans had been dispatched earlier in the day to ensure that Kapyong remained in UN hands, and one of the battalions was subsequently deployed to the southwest of the D Company, 2 PPCLI on the summit of Hill 677 in order to cover the left flank. A second American battalion occupied a position across the river, southeast of the Middlesex. Likewise, despite heavy casualties in one of the Australian companies and battalion headquarters, 3 RAR had emerged from the intense battle largely intact and had successfully withdrawn in an orderly fashion. Meanwhile, one of the replacement British battalions, the 1. prapor, King's Own Scottish Borderers, had also arrived during the 24th and it took up positions with the Australians around Brigade Headquarters. With six UN battalions now holding the valley the PVA faced a difficult task continuing the advance.[81]

Having dislodged the defenders from Hill 504, the PVA 354th Regiment, 118th Division would attempt to capture the dominating heights of Hill 677 held by the Canadians.[94] Although unaware of the arrival of American reinforcements, the PVA had however detected the redeployment of B Company, 2 PPCLI and at 22:00 that evening they commenced an assault on the Canadian right flank.[95] Although the initial moves were easily beaten back by automatic fire and mortars, a second PVA assault an hour later succeeded in overrunning the right forward platoon. The Canadians successfully withdrew in small groups back to the company main defensive position, where they eventually halted the PVA advance.[96] During the fighting the Canadians' 60-millimetre (2.4 in) mortars had proven vital, their stability allowing for rapid fire out to 1,800 metres (2,000 yd) with an ability to accurately hit narrow ridgelines at maximum range.[81] The next morning 51 PVA dead were counted around the B Company perimeter.[96] Shortly after the second assault on B Company was repelled, another large PVA assault force was detected fording the river in the bright moonlight. Laying down heavy and accurate artillery fire, the New Zealand gunners forced the PVA to withdraw, killing more than 70.[97]

Meanwhile, a large PVA force of perhaps company strength was detected in the re-entrant south of B Company, moving toward Battalion Headquarters, and Lilley warned Stone of the impending assault. Šest M3 Polopásy from Mortar Platoon had been positioned there before the battle, each armed with a .50-calibre and a .30-calibre machine gun. Stone held fire until the PVA broke through the tree-line just 180 metres (200 yd) from their front. The Canadians opened fire with machine guns and with mortars at their minimum engagement distance. The PVA suffered severe casualties and the assault was easily beaten off.[96] The PVA had telegraphed their intentions prior to the assault by using sledovač fire for direction, and had used bugles to co-ordinate troops in their forming up positions. Such inflexibility had allowed the Canadians to co-ordinate indirect fires and took a heavy toll on the attackers in the forming up positions.[98]

The PVA had been unable to successfully pinpoint the Canadian defensive positions, having failed to carry out a thorough reconnaissance prior to the attack. The severe terrain had also prevented the assaulting troops from adopting a low profile during their final assault, however in the darkness the Canadian rifle fire was ineffective, forcing them to resort to using grenades and rocket launchers.[98] The PVA mortars and artillery was particularly ineffective however, and very few rounds fell on the Canadian positions during the evening. Indeed, in their haste to follow up the collapse of the ROK 6th Division, the PVA 118th Division had left the bulk of its artillery and supplies well to the north. Meanwhile, what mortar ammunition they did have had been largely used up on the Australians during the previous evening. In contrast, the New Zealand gunners provided effective fire support and had been able to break up a number of PVA assaults before they had even reached the Patricias. The PVA now turned their attention to D Company holding the summit of Hill 677, on the battalion's left flank.[97]

At 01:10 a large PVA force was detected forming up on a spur to the west towards Hill 865 and they were engaged by Bren guns and defensive fires. Assaulting 10 Platoon under the cover of machine-gun and mortar fire, the PVA were soon effectively engaged by Vickers machine guns from 12 Platoon firing in mutual support. Switching their axis of assault to 12 Platoon, the PVA succeeded in overrunning one of the Canadian sections and a medium machine gun, killing two of its crew who had remained at their post firing until the last moment. The Canadians fought back, engaging the PVA as they attempted to turn the Vickers on them, rendering it inoperable before calling in pre-arranged defensive fires on to the newly lost position.[99] With the supporting artillery firing at the 'very slow' rate to conserve ammunition, the weight of the PVA assaults soon prompted the Canadians to request it be increased to the 'slow' rate of two rounds per gun per minute, so that 24 rounds fell every 30 seconds within a target area of 180 metres (200 yd).[100]

With the PVA infiltrating the Canadian perimeter through the gaps between platoons, D Company was close to being surrounded. The company commander, Captain J.G.W. Mills, was subsequently forced to call down artillery fire onto his own position on several occasions during the early morning of 25 April to avoid being overrun. The tactic succeeded and the exposed PVA were soon swept off the position, while the dug-in Canadians escaped unharmed. The PVA persisted however, launching a number of smaller attacks during the rest of the night, but these were again repulsed by artillery and small arms fire. By dawn the attacks on the Canadian positions had abated, and with D Company remaining in control of the summit they were able to recover the previously abandoned machine gun at first light. Meanwhile, on the right flank B Company was also able to re-occupy the platoon position it had been forced to relinquish earlier the previous evening.[100] The PVA had suffered heavily during the night, with perhaps as many as 300 killed by the Patricias.[101]

Fighting concludes, 25 April 1951

Although the PVA had continued to mount small attacks, UN forces were now in control of the battle. Regardless, the PVA had succeeded in establishing blocking positions on the roads south of the Canadians, temporarily cutting them off from resupply. Anticipating that the battle would continue into the evening, Stone requested that food, ammunition, and water be airdropped directly onto Hill 677 and by 10:30 the required supplies—including 81-millimetre (3.2 in) mortar ammunition—were dropped by four American C-119 Flying Boxcars flying from an airbase in Japan. Anticipating a renewed PVA effort, the Canadians continued to improve their defensive position. Meanwhile, the Middlesex sent out patrols during the morning in order to clear the PVA that had infiltrated behind Hill 677 during the evening, and although the PVA blocking positions were relatively weak it was not until 14:00 that patrols from B Company, 2 PPCLI reported the road clear. Stone subsequently requested that further supplies and reinforcements be sent forward by vehicle as rapidly as feasible.[100]

The remainder of the day was relatively quiet for the Canadians, although they were subjected to periodic harassing fire from the PVA. D Company received heavy machine-gun fire from Hill 865 to the west, in particular. Regardless, the PVA made no further attempt to attack, and confined themselves to limited patrolling activities across the front. Later the Patricias, with American tanks in support, cleared the remaining PVA from the northern slopes of Hill 677, while several PVA concentrations were again broken up by heavy artillery fire and airstrikes. The American battalion on the south-west flank of the Canadians was subsequently relieved by the Middlesex, following which the 5th US Cavalry Regiment launched an assault to recover Hill 504. The PVA resisted until 16:00, before the 118th Division suddenly withdrew. American patrols north of the feature met no resistance, while the Americans were also able to patrol east along Route 17 to Chunchon without contact. By last light the situation had stabilised on the Kapyong Valley front.[101] Having left their supplies of food and ammunition far behind during the advance two days earlier, the PVA had been forced to withdraw back up the Kapyong Valley in the late afternoon of 25 April in order to regroup and replenish following the heavy casualties incurred during the fighting.[101][102]

Následky

Ztráty

With vastly superior numbers the PVA had attacked on a broad front, and had initially overrun a number of the forward UN positions. Regardless, the 27th Brigade had ultimately prevailed despite being outnumbered by a factor of five to one.[103] Indeed, despite their numerical advantage the PVA had been badly outgunned and they could not overcome the well-trained and well-armed Australians and Canadians.[68] Bojiště bylo plné mrtvol vojáků PVA, což svědčí o disciplíně a palebné síle obránců. And yet, despite their ultimate defeat, the battle once again demonstrated that the PVA were tough and skillful soldiers capable of inflicting heavy casualties on the Australians and forcing their eventual withdrawal, albeit both intact and orderly.[49] As a result of the fighting Australian losses were 32 killed, 59 wounded and three captured, while Canadian casualties included 10 killed and 23 wounded.[93] American casualties included three men killed, 12 wounded and two tanks destroyed, all from A Company, 72nd Heavy Tank Battalion. The New Zealanders lost two killed and five wounded.[41] In contrast, PVA losses were far heavier, and may have included 1,000 killed and many more wounded.[93][101] The Canadians were finally relieved on Hill 677 by a battalion of the 5th US Cavalry Regiment on the evening 26 April.[104]

2 PPCLI, 3 RAR and A Company, 72nd Heavy Tank Battalion were all subsequently awarded the US Presidential Unit Citation for their actions during the Battle of Kapyong. The New Zealand gunners—without whom the Australians and Canadians may have suffered a similar fate to that of Glosters at the Imjin—were awarded the South Korean Presidential Unit Citation.[49] Although the Canadians and Australians had borne the brunt of the fighting, the Middlesex—despite the imminence of their replacement—had shown no evidence of hesitancy or lack of aggression when recalled into the fighting early in the battle.[40] For their leadership, Ferguson and Stone were both awarded the Distinguished Service Order, while Koch was awarded both the American Distinguished Service Cross and the British Military Cross for the vital part his tanks had played in the fighting.[77][poznámka 7] The Královský australský regiment, Princess Patricia's Canadian Light Infantry and the Middlesex Regiment were subsequently granted the bitevní čest "Kapyong".[7][105] Today, the battle is regarded one as the most famous actions fought by the Australian and Canadian armies in Korea.[26]

Následné operace

By 29 April, Chinese Spring Offensive was halted by UN forces at a defensive line north of Seoul, known as the Řádek bez jména; in total a withdrawal of 56 kilometres (35 mi) in the US I and IX Corps sectors, and 32 kilometres (20 mi) in the US X Corps and ROK III. Sbor odvětví.[106] Although the main blow had fallen on US I Corps, the resistance by British Commonwealth forces in the battles at the Imjin River and at Kapyong had helped to blunt its impetus, with the defence mounted by the 27th Brigade stopping the PVA from isolating US I Corps from US IX Corps, thereby helping to halt the PVA advance on Seoul and preventing its capture.[68][107] The PVA had now nearly exhausted their resources of men and material, and were approaching the limit of their napájecí vedení. Many PVA soldiers were now tired, hungry and short of equipment and during the fighting at Kapyong they had demonstrated a greater willingness to surrender than in previous encounters, with 3 RAR alone taking 39 prisoners, only eight of them wounded. Contingent on the rapid attainment of its objectives, the attempted PVA státní převrat ultimately failed amid heavy casualties and they had little recourse but to abandon their attacks against US I and IX Corps.[49][108] The PVA had suffered at least 30,000 casualties during the period 22–29 April.[109] In contrast, US casualties during the same period numbered just 314 killed and 1,600 wounded, while Commonwealth, ROK and other UN contingents brought the total to 547 killed, 2,024 wounded and 2,170 captured; the disparity highlighting the devastating effect of enormous UN firepower against massed infantry.[110][111] Undeterred by these setbacks, the Second Phase of the Spring Offensive began on 16 May to the east of Kapyong, only to suffer their worst defeat at the Bitva u řeky Sojang.[112]

27th Brigade was replaced by the 28. britská brigáda společenství and Brigadier George Taylor took over command of the new formation on 26 April. With the PVA offensive losing momentum, the new Commonwealth formation was subsequently pulled back into IX Corps reserve to the southwest of Kapyong, near the junction of the Pukhan and Chojon rivers. 3 RAR was transferred to 28th Brigade, while the 1st Battalion, The King's Own Scottish Borderers and the 1st Battalion, The King's Shropshire Light Infantry replaced the Argylls and Middlesex regiments. Later, the Patricias were transferred to the newly arrived 25th Canadian Brigade on 27 May.[113][114] After protracted negotiations between the governments of Australia, Britain, Canada, India, New Zealand and South Africa, agreement had been reached to establish an integrated formation with the aim of increasing the political significance of their contribution, as well as facilitating the solution of the logistic and operational problems faced by the various Commonwealth contingents.[113] The 1. divize společenství was formed on 28 July 1951, with the division including the 25th Canadian, 28th British Commonwealth and 29th British Infantry Brigades under the command of Major General James Cassels, and was part of US I Corps.[115] For many of the Australians Kapyong was to be their last major battle before completing their period of duty and being replaced, having endured much hard fighting, appalling weather and the chaos and confusion of a campaign that had ranged up and down the length of the Korean Peninsula. Most had served in the Druhá australská imperiální síla (2nd AIF) during the Druhá světová válka and this combat experience had proven vital.[116] Regardless, casualties had been heavy, and since the battalion's arrival from Japan in September 1950 the Australians had lost 87 killed, 291 wounded and five captured.[117]

Viz také

- Gapyeong Canada Monument

- Kapyong (2011) – documentary about the battle

- Pamětní hřbitov OSN, Pusan, Jižní Korea – where many of the Australian and Canadian casualties are buried

Poznámky

Poznámky pod čarou

- ^ The Chinese military did not have hodnosti during the 1950s, except for the title of "Commander" or "Commissar".

- ^ In Chinese military nomenclature, the term "Army" (军) means Sbor, while the term "Army Group" (集团军) means Polní armáda.

- ^ O'Neill identifies the PVA 60th Division; however, the 60th Division maintained its south-westerly course as part of the 20th Army and had not pursued the ROK 19th Infantry Regiment after routing it in the Kapyong valley. The division next contacted the US 24th Division in the I Corps sector. See Mossman 1990, p. 402 and O'Neill 1985, p. 134.

- ^ During his captivity Madden resisted repeated Chinese and North Korean attempts to make him collaborate, despite repeated beatings and being deprived of food. He remained cheerful and optimistic for six months, sharing his meagre food with other prisoners who were sick. He grew progressively weaker though and died of malnutrition on 6 November 1951. For his conduct he was posthumously awarded the George Cross. See O'Neill 1985, p. 147.

- ^ Controversy surrounds the circumstances of this accident. While the Australian official historian states that Gravener requested the airstrike, it seems neither Gravener nor O'Dowd called for air support that afternoon, and it is more likely the request came from either Ferguson or Brigade Headquarters. See O'Neill 1985, p. 153 and Breen 1992, p. 97.

- ^ There is some disagreement between sources on the timing of the withdrawal, with some sources nominating 15:30, while others claim it began at 17:30. The time of 16:00 is based on an account by O'Dowd himself. See Breen 1992, p. 93.

- ^ For Stone it was his second such award, winning his first DSO at the Bitva u Ortony in Italy in 1943. See Johnston 2003, p. 30.

Citace

- ^ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 377.

- ^ A b Hu & Ma 1987, s. 51.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 121.

- ^ A b O'Neill 1985, s. 123.

- ^ A b C d O'Neill 1985, s. 132.

- ^ A b O'Neill 1985, pp. 125–127.

- ^ A b C Horner 1990, s. 444.

- ^ A b Breen 1992, p. 12.

- ^ A b Butler, Argent a Shelton 2002, s. 103.

- ^ Butler, Argent a Shelton 2002, s. 77.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 107.

- ^ A b O'Neill 198, p. 134.

- ^ Varhola 2000, pp. 88, 278.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 125.

- ^ A b O'Neill 1985, s. 127.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 128.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 20.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, pp. 128–129.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 129.

- ^ A b C d O'Neill 1985, s. 131.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 18.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 21.

- ^ Farrar-Hockley 1995, p. 109.

- ^ Zhang 1995, p. 145.

- ^ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, pp. 309, 326.

- ^ A b C d E F G Coulthard Clark 2001, p. 263.

- ^ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 312.

- ^ Johnston 2003, p. 89.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Johnston 2003, pp. 90–91.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 401.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 382.

- ^ A b C Chae, Chung and Yang 2001, p. 630.

- ^ A b C d Horner 2008, s. 69.

- ^ A b C d Mossman 1990, p. 402.

- ^ A b C d Johnston 2003, p. 91.

- ^ A b Zhang 1995, p. 149.

- ^ Johnston 2003, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 391.

- ^ A b Horner 2008, s. 68.

- ^ A b C d E F "The Battle of Kapyong, April 1951". The Australian War Memorial. Citováno 23. ledna 2010.

- ^ Horner 2008, pp. 69–70.

- ^ Johnston 2003, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Johnston 2003, p. 95.

- ^ A b C d E Horner 2008, s. 70.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 40.

- ^ Chinese Military Science Academy 2000, p. 314.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 25.

- ^ A b C d E F Horner 2008, s. 71.

- ^ O'Dowd 2000, p. 165.

- ^ Breen 1992, pp. 113–114.

- ^ A b C "No. 39448". London Gazette. 25. ledna 1952. str. 514.

- ^ A b O'Neill 1985, s. 142.

- ^ Johnston 2003, p. 96.

- ^ "No. 39703". London Gazette. 25 November 1952. p. 6214.

- ^ A b C O'Neill 1985, s. 143.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 100.

- ^ A b O'Neill 1985, s. 144.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, pp. 145–146.

- ^ A b O'Neill 1985, s. 148.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, pp. 146–147.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 642.

- ^ „Č. 40665“. London Gazette (Doplněk). 27. prosince 1955. str. 7299.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 147.

- ^ A b C d E F Coulthard-Clark 2001, str. 264.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 403.

- ^ A b Breen 1992, pp. 46–47.

- ^ A b C "Out in the Cold: Australia's involvement in the Korean War – Kapyong 23–24 April 1951". The Australian War Memorial. Citováno 24. ledna 2010.

- ^ Kuring 2004, s. 235.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 119.

- ^ Johnston 2003, pp. 97–98, 106.

- ^ A b O'Neill 1985, s. 149.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, pp. 148–149.

- ^ A b C d E O'Neill 1985, s. 150.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, pp. 149–150.

- ^ A b C "No. 39312". London Gazette. 17 August 1951. p. 4382.

- ^ A b O'Neill 1985, s. 151.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 152.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, pp. 152–153.

- ^ Johnston 2003, p. 98.

- ^ A b C Johnston 2003, p. 99.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 86.

- ^ A b C d Johnston 2003, p. 97.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 91.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 92.

- ^ A b C Breen 1992, p. 93.

- ^ Breen 1992, pp. 95–96.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 153.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, pp. 153–154.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 154.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, pp. 156–157.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 155.

- ^ A b C d Coulthard-Clark 2001, str. 265.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 635.

- ^ Johnston 2003, pp. 99–100.

- ^ A b C Johnston 2003, p. 100.

- ^ A b Johnston 2003, p. 102.

- ^ A b Johnston 2003, p. 101.

- ^ Johnston 2003, pp. 102–103.

- ^ A b C Johnston 2003, p. 103.

- ^ A b C d Johnston 2003, p 104.

- ^ Kuring 2004, s. 237.

- ^ Brooke, Michael (20 April 2006). "3 RAR's Priority on Duty". Army News (1142 ed.). Australské ministerstvo obrany. Archivovány od originál dne 4. června 2013. Citováno 24. ledna 2010.

- ^ Johnston 2003, p. 106.

- ^ Rodger 2003, p. 373.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 436.

- ^ Chae, Chung & Yang 2001, p. 636.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 160.

- ^ Millett 2010, p. 434.

- ^ Mossman 1990, p. 437.

- ^ Johnston 2003, p. 108.

- ^ Appleman 1990, pp. 509, 550.

- ^ A b O'Neill 1985, s. 166.

- ^ Johnston 2003, p. 107.

- ^ Grey 1988, pp. 192–195.

- ^ Breen 1992, p. 104.

- ^ O'Neill 1985, s. 158.

Reference

- Appleman, Roy (1990). Ridgway Duels for Korea. Série vojenské historie. Volume 18. College Station, Texas: Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 978-0-89096-432-3.

- Breen, Bob (1992). Bitva o Kapyong: 3. prapor, královský australský pluk, Korea 23. – 24. Dubna 1951. Georges Heights, New South Wales: Headquarters Training Command, Australian Army. ISBN 978-0-642-18222-7.

- Butler, David; Argent, Alf; Shelton, Jim (2002). The Fight Leaders: Australian Battlefield Leadership: Green, Hassett and Ferguson 3RAR – Korea. Loftus, Nový Jižní Wales: Australské vojenské historické publikace. ISBN 978-1-876439-56-9.

- Chae, Han Kook; Chung, Suk Kyun; Yang, Yong Cho (2001). Yang, Hee Wan; Lim, vyhrál Hyok; Sims, Thomas Lee; Sims, Laura Marie; Kim, Chong Gu; Millett, Allan R. (eds.). Korejská válka. Svazek II.Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press. ISBN 978-0-8032-7795-3.

- Čínská akademie vojenské vědy (2000). History of War to Resist America and Aid Korea (抗美援朝 战争 史) (v čínštině). Svazek II. Peking: Nakladatelství Čínské vojenské vědecké akademie. ISBN 978-7-80137-390-8.

- Coulthard-Clark, Chris (2001). Encyklopedie australských bitev (Druhé vydání.). Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-86508-634-7.

- Farrar-Hockley, Anthony (1995). Britská část korejské války: Čestné absolutorium. Svazek II. Londýn: HMSO. ISBN 978-0-11-630958-7.

- Gray, Jeffrey (1988). Armády společenství a korejská válka: Alianční studie. Manchester, Velká Británie: Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-2770-3.

- Horner, David, vyd. (1990). Duty First: The Royal Australian Regiment in War and Peace (První vydání). North Sydney, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-0-04-442227-3.

- Horner, David, ed. (2008). Duty First: Historie královského australského regimentu (Druhé vydání.). Crows Nest, New South Wales: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 978-1-74175-374-5.

- Hu, Guang Zheng (胡光 正); Ma, Shan Ying (马 善 营) (1987). Řád bitvy čínské lidové dobrovolnické armády (中国 人民 志愿军 序列) (v čínštině). Peking: Nakladatelství Čínské lidové osvobozenecké armády. OCLC 298945765.

- Johnston, William (2003). Válka hlídek: operace kanadské armády v Koreji. Vancouver, Britská Kolumbie: UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-1008-1.

- Kuring, Ian (2004). Redcoats to Cams: A History of Australian Infantry 1788–2001. Loftus, Nový Jižní Wales: Australské vojenské historické publikace. ISBN 978-1-876439-99-6.

- Millett, Allan R. (2010). Válka o Koreu, 1950–1951: Přišli ze severu. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-1709-8.

- Mossman, Billy C. (1990). Armáda Spojených států v korejské válce: Ebb and Flow: listopad 1950 - červenec 1951. Washington D.C .: Centrum vojenské historie, americká armáda. ISBN 978-1-131-51134-4.

- O'Dowd, Ben (2000). In Valiant Company: Diggers in Battle - Korea, 1950–51. Svatá Lucie, Queensland: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-7022-3146-9.

- O'Neill, Robert (1985). Austrálie v korejské válce 1950–1953: bojové operace. Svazek II. Canberra, Území hlavního města Austrálie: Australský válečný památník. ISBN 978-0-642-04330-6.

- Rodger, Alexander (2003). Vyznamenání bitvy britského impéria a pozemních sil společenství 1662–1991. Marlborough, Velká Británie: The Crowood Press. ISBN 1-86126-637-5.

- Varhola, Michael J. (2000). Oheň a led: Korejská válka, 1950–1953. Mason City, Iowa: Da Capo Press. ISBN 978-1-882810-44-4.

- Zhang, Shu Guang (1995). Maův vojenský romantismus: Čína a korejská válka, 1950–1953. Lawrence, Kansas: University Press of Kansas. ISBN 978-0-7006-0723-5.

Další čtení

- Bercuson, David (2001). Patricias: Pyšná historie bojového pluku. Toronto: Stoddart Publishing. ISBN 9780773732988.

- Forbes, Cameron (2010). Korejská válka: Austrálie na hřišti obrů. Sydney, Nový Jižní Wales: Macmillan. ISBN 978-1-405040-01-3.

- McGibbon, Ian (1996). Nový Zéland a korejská válka. Bojové operace. Svazek II. Auckland, Nový Zéland: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-558343-4.

- Hrušky, Maurie (2007). Battlefield Korea: Korejské vyznamenání královského australského pluku, 1950–1953. Loftus, New South Wales: Australian Military History Publications. ISBN 9780980379600.

- Thompson, Peter; Macklin, Robert (2004). Keep off the Skyline: The Story of Ron Cashman and the Diggers in Korea. Milton, Queensland: Wiley. ISBN 1-74031-083-7.